Assessment of Sport and Physical Recreation Participation for Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

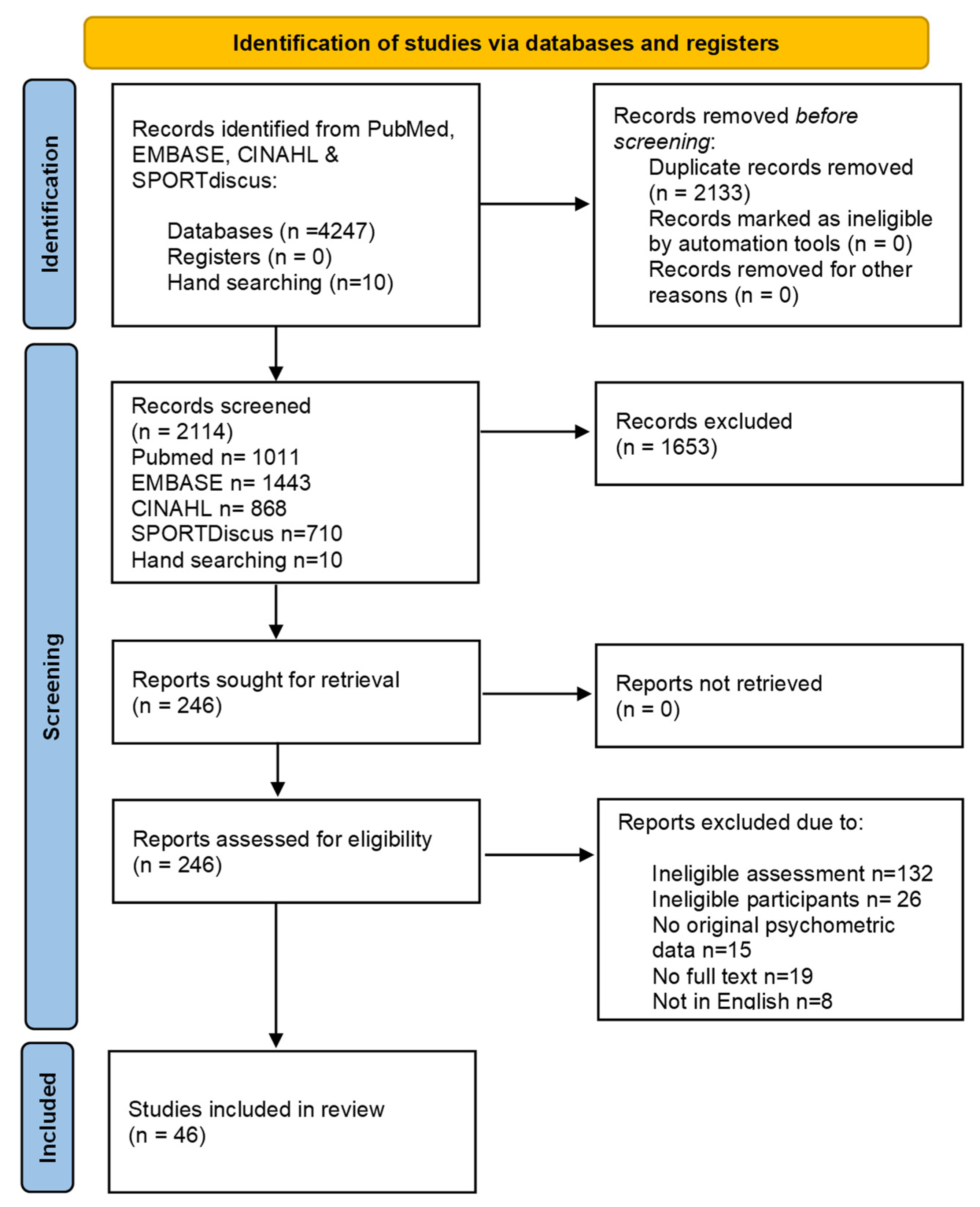

2. Methods

2.1. Registration

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- They reported on assessments that

- evaluated participation [49], including at least one of the following:

- Attendance diversity (what activity) +/− frequency (how often, or for how long) or

- Involvement.

- They were relevant to sport and physical recreation, either because they included

- ≥20% sport or physical recreation specific items or

- a subscale specific to sport and/or physical recreation, regardless of the overall make-up of the assessment.

- They included original psychometric data on validity or reliability

- for children or youth with disabilities aged 0–24 years or

- for any population if the paper reported on the original development of an included assessment.

- They were full-text papers, written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.5. Assessment Content

2.5.1. Sport

“A human activity involving physical exertion and skill as the primary focus of the activity, with elements of competition where rules and patterns of behaviour governing the activity exist formally through organisations and is generally recognised as a sport.”(p. 7)

2.5.2. Physical Recreation

“Activities engaged in for the purpose of relaxation, health and wellbeing or enjoyment with the primary activity requiring physical exertion, and the primary focus on human activity.”(p. 7)

2.6. Assessment Psychometrics

2.7. Recommendations

3. Results

3.1. Excluded Assessments

3.2. Content of Assessments

3.3. Populations Evaluated

3.4. Proportion of Relevant Items

3.5. Participation Construct

3.6. Data Type

3.7. Quality of Evidence for Psychometric Properties

3.8. Validity

3.9. Reliability

3.10. GRADE Summary

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- te Velde, S.; Lankhorst, K.; Zwinkels, M.; Verschuren, O.; Takken, T.; de Groot, J. Associations of sport participation with self-perception, exercise self-efficacy and quality of life among children and adolescents with a physical disability or chronic disease—A cross-sectional study. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braaksma, P.; Stuive, I.; Garst, R.; Wesselink, C.F.; van Der Sluis, C.K.; Dekker, R.; Schoemaker, M.M. Characteristics of physical activity interventions and effects on cardiorespiratory fitness in children aged 6–12 years—A systematic review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efrat, M. The Relationship Between Low-Income and Minority Children’s Physical Activity and Academic-Related Outcomes: A Review of the Literature. Health Educ. Behav. 2011, 38, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Zahner, L.; Puhse, U.; Puder, J.J.; Kriemler, S. Effects of a School-Based Physical Activity Program on Physical and Psychosocial Quality of Life in Elementary School Children: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2010, 22, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allender, S.; Cowburn, G.; Foster, C. Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: A review of qualitative studies. Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, T.; Bowling, A.; Davison, K.; Garcia, J. Physical Activity Interventions for Children with Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Disabilities—A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2017, 38, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. Systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 822. [Google Scholar]

- Lankhorst, K.; van der Ende-Kastelijn, K.; de Groot, J.; Zwinkels, M.; Verschuren, O.; Backx, F.; Visser-Meily, A.; Takken, T. Health in Adapted Youth Sports Study (HAYS): Health effects of sports participation in children and adolescents with a chronic disease or physical disability. Springerplus 2015, 4, 796. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.A.; Toohey, M.; Ferguson, M. Physical activity predicts quality of life and happiness in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, C.D.; Vos, E.T.; Stevenson, C.E.; Begg, S.J. The burden of disease and injury in Australia. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Description of the Global Burden of NCDs, Their Risk Factors and Determinants; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, D.G.; Warschausky, S.A.; Peterson, M.D. Mental health disorders and physical risk factors in children with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Andersen, L.B.; Armstrong, N.; Biddle, S.; Boreham, C.; Bedenbeck, H.-P.B.; Ekelund, U.; Engebretsen, L.; Hardman, K.; Hills, A.; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on the health and fitness of young people through physical activity and sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Madaan, V.; Petty, F.D. Exercise for mental health. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sport Australia. Australian Physical Literacy Framework. Version 2. Canberra: Sport Australia; 2019. Available online: https://www.sportaus.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/710173/35455_Physical-Literacy-Framework_access.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Feitosa, L.C.; Muzzolon, S.R.B.; Rodrigues, D.C.B.; Crippa, A.C.d.S.; Zonta, M.B. The effect of adapted sports in quality of life and biopsychosocial profile of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2017, 35, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clutterbuck, G.L.; Sousa Junior, R.R.d.; Leite, H.R.; Johnston, L.M. The SPORTS Participation Framework: Illuminating the pathway for people with disability to enter into, participate in, and excel at sport. Rev. Bras. Fisioter. 2024, 28, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohle, S.; Wansink, B. Fit in 50 years: Participation in high school sports best predicts one’s physical activity after Age 70. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Gordon, W.A. Impact of impairment on activity patterns of children. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1987, 68, 828–832. [Google Scholar]

- Capio, C.; Sit, C.; Abernethy, B.; Masters, R. Fundamental movement skills and physical activity among children with and without cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.P.; Evans, M.B.P.; Mortenson, W.B.P.; Noreau, L.P. Broadening the Conceptualization of Participation of Persons with Physical Disabilities: A Configurative Review and Recommendations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, C.; Granlund, M.; Wilson, P.H.; Steenbergen, B.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Gordon, A.M. Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, C.; Adair, B.; Keen, D.; Ullenhag, A.; Rosenbaum, P.; Granlund, M. ‘Participation’: A systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Curtin, M.; Clutterbuck, G.L. Breaking down participation in sport and physical recreation for children with disabilities: What it means and what can be seen. Sport Sci. Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Lee, E.; Frey, G.; Jung, T.; Wagatsuma, M.; Stanish, H.; Rimmer, J.H. Research trends and recommendations for physical activity interventions among children and youth with disabilities: A review of reviews. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. APAQ 2020, 37, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, G.; Adair, B.; Stott, N.S.; Steele, M.; Hogan, A.; Imms, C. Do physical activity interventions influence subsequent attendance and involvement in physical activities for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 1682–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubala, A.; MacGillivray, S.; Frost, H.; Kroll, T.; Skelton, D.A.; Gavine, A.; Gray, N.M.; Toma, M.; Morris, J. Promotion of physical activity interventions for community dwelling older adults: A systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.; Bridges, S.; Corrins, B.; Pham, J.; White, C.; Buchanan, A. The impact of physical activity and sport programs on community participation for people with intellectual disability: A systematic review. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 46, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Foster, C.; Lai, B.; McBride, C.B.; Ng, K.; Pratt, M.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Smith, B.; Vásquez, P.M.; et al. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: A global perspective. Lancet 2021, 398, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, G.W.; Levine, D. Physical Activity and Public Health among People with Disabilities: Research Gaps and Recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa Junior, R.R.d.; Souto, D.O.; Camargos, A.C.R.; Clutterbuck, G.L.; Leite, H.R. Moving together is better: A systematic review with meta-analysis of sports-focused interventions aiming to improve physical activity participation in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 2398–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Junior, R.R.; Sousa, A.B.; de Lima, A.F.B.; de Barros Santos-Rehder, R.; Simão, C.R.; Fischer, G.; Camargos, A.C.R.; Clutterbuck, G.L.; Leite, H.R. Modified sports interventions for children and adolescents with disabilities: A scoping review. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2024, 66, 1432–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, G.L.; Auld, M.L.; Johnston, L.M. SPORTS STARS: A practitioner-led, peer-group sports intervention for ambulant children with cerebral palsy. Activity and participation outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, K.G.; Lange, M.A. Comparison of physical activity questionnaires for the elderly with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)—An analysis of content. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.C.; Aguiar, L.T.; Nadeau, S.; Scianni, A.A.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.F.; Faria, C.D.C.D.M. Measurement properties of self-report physical activity assessment tools for patients with stroke: A systematic review. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 23, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankhorst, K.; Oerbekke, M.; van den Berg-Emons, R.; Takken, T.; de Groot, J. Instruments Measuring Physical Activity in Individuals Who Use a Wheelchair: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirard, J.R.; Pate, R.R. Physical Activity Assessment in Children and Adolescents. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, H.W.; Fulton, J.E.; Caspersen, C.J. Assessment of Physical Activity among Children and Adolescents: A Review and Synthesis. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, S54–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakzewski, L.; Boyd, R.; Ziviani, J. Clinimetric properties of participation measures for 5- to 13-year-old children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2007, 49, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.-W.; Rodger, S.; Copley, J.; Skorka, K. Comparative Content Review of Children’s Participation Measures Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health–Children and Youth. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-H.M.P.H.O.T.R.; Coster, W.J.P.O.T.R.L.; Helfrich, C.A.P.O.T.R.L. Community Participation Measures for People with Disabilities: A Systematic Review of Content From an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Perspective. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekins, T.P.D.; Shunkamolah, W.B.A.; Bertsche, M.B.A.; Cowart, C.B.A.; Summers, J.A.P.D.; Reichard, A.P.D.; White, G.P.D. A systematic scoping review of measures of participation in disability and rehabilitation research: A preliminary report of findings. Disabil. Health J. 2012, 5, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziviani, J.; Desha, L.; Feeney, R.; Boyd, R. Measures of Participation Outcomes and Environmental Considerations for Children with Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Brain Impair. 2010, 11, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Fitzpatrick, R. Child or family assessed measures of activity performance and participation for children with cerebral palsy: A structured review. Child Care Health Dev. 2005, 31, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey, L.; Van Nispen, R.; Van Der Zee, C.; Van Rens, G. Measurement properties of questionnaires assessing participation in children and adolescents with a disability: A systematic review. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2014, 23, 2793–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.A.; Kim, H. Child and adolescent participation measurement tools and their translations: A systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2024, 50, e13248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clanchy, K.M.; Tweedy, S.M.; Boyd, R. Measurement of habitual physical activity performance in adolescents with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, G.L.; Auld, M.L.; Johnston, L.M. High-level motor skills assessment for ambulant children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and decision tree. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2020, 62, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.L.; Stockton, K.; Wilson, C.; Russell, T.G.; Johnston, L.M. Exercise testing for children with cystic fibrosis: A systematic review. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 1996–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerackody, S.C.; Clutterbuck, G.L.; Johnston, L.M. Measuring psychological, cognitive, and social domains of physical literacy in school-aged children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A systematic review and decision tree. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 3456–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.A.; Law, M.; King, S.; Hurley, P.; Hanna, S.; Kertoy, M.; Rosenbaum, P. Measuring children’s participation in recreation and leisure activities: Construct validation of the CAPE and PAC. Child Care Health Dev. 2007, 33, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, S.; Sachs, D.; Schreuer, N. Reliability and validity of the Children’s Leisure Assessment Scale. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2010, 64, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, B.A.; Ardovino, P.; Hsieh, C.M. Validity and reliability of the Leisure Assessment Inventory. Ment. Retard. 1998, 36, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandich, A.; Polatajko, H.; Miller, L. Paediatric Activity Card Sort (PACS); CAOT Publications ACE: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, C.; Lavesser, P. The Preschool Activity Card Sort. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2006, 26, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, K.C.; Crocker, P.R.E.; Donen, R.M. The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) and Adolescents (PAQ-A) Manual; College of Kinesiology, University of Saskatchewan: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, J.G.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Rocchi, M.; Sweet, S.N. Development of the Measure of Experiential Aspects of Participation for People with Physical Disabilities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 67–77.e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljenquist, K.S. Developing a Self-Report Measure of Participatory Experience, Skill Development and Environmental Influence and a Measure of Environment Affordances for Youth with Intellectual Disabilities: The Participatory Experience Survey and the Setting Affordances Survey. Ph.D. Thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- King, G.; Batorowicz, B.; Rigby, P.; Pinto, M.; Thompson, L.; Goh, F. The leisure activity settings and experiences of youth with severe disabilities. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2014, 17, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.A.; Law, M.; King, S.; Hurley, P.; Hanna, S.; Kertoy, M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Young, N. Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC); PsychCorp: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Almasri, N.A.; Palisano, R.J.; Kang, L.J. Cultural adaptation and construct validation of the Arabic version of children’s assessment of participation and enjoyment and preferences for activities of children measures. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiadi, I.; Tzetzis, G. Construct validation of the Greek version of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC). J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, R.M.; Senesac, C.; Lott, D.J.; Vandenborne, K. Participation and quality of life in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bult, M.; Verschuren, O.; Lindeman, E.; Jongmans, M.; Ketelaar, M. Do children participate in the activities they prefer? A comparison of children and youth with and without physical disabilities. Clin. Rehabil. 2014, 28, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bult, M.K.; Verschuren, O.; Gorter, J.W.; Jongmans, M.J.; Piskur, B.; Ketelaar, M. Cross-cultural validation and psychometric evaluation of the Dutch language version of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) in children with and without physical disabilities. Clin. Rehabil. 2010, 24, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón, W.I.; Rodríguez, C.; Ito, M.; Reed, C.N. Psychometric evaluation of the Spanish version of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment and Preferences for Activities of Children. Occup. Ther. Int. 2008, 15, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel-Yeger, B.; Jarus, T.; Anaby, D.; Law, M. Differences in patterns of participation between youths with cerebral palsy and typically developing peers. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 63, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A.; Gebhard, B.; Erdwiens, S.; Haddenhorst, L.; Nowak, S. Reliability of the German version of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC). Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.S.M.; Lee, V.Y.L.; Chan, N.N.C.; Chan, R.S.H.; Chak, W.-K.; Pang, M.Y.C. Motor ability and weight status are determinants of out-of-school activity participation for children with developmental coordination disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 2614–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassani Mehraban, A.; Hasani, M.; Amini, M. The Comparison of Participation in School-Aged Cerebral Palsy Children and Normal Peers: A Preliminary Study. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2016, 26, e5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, C.L.; Crouch, M.C.; Israel, H. Out-of-school participation patterns in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2008, 62, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarus, T.; Lourie-Gelberg, Y.; Engel-Yeger, B.; Bart, O. Participation patterns of school-aged children with and without DCD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Shields, N.; Imms, C.; Black, M.; Ardern, C. Participation of children with intellectual disability compared with typically developing children. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 1854–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaas, S.J.; Kelly, E.H.; Gorzkowski, J.; Homko, E.; Vogel, L.C. Assessing patterns of participation and enjoyment in children with spinal cord injury. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2010, 52, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; King, G.; King, S.; Kertoy, M.; Hurley, P.; Rosenbaum, P.; Young, N.; Hanna, S. Patterns of participation in recreational and leisure activities among children with complex physical disabilities. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2006, 48, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, E.; Badia, M.; Orgaz, B.; Verdugo, M.A. Cross-cultural validation of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) in Spain. Child. Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majnemer, A.; Shevell, M.; Law, M.; Birnbaum, R.; Chilingaryan, G.; Rosenbaum, P.; Poulin, C. Participation and enjoyment of leisure activities in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2008, 50, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnemer, A.; Shikako-Thomas, K.; Schmitz, N.; Shevell, M.; Lach, L. Stability of leisure participation from school-age to adolescence in individuals with cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordtorp, H.L.; Nyquist, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Moser, T.; Strand, L.I. Reliability of the Norwegian version of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC). Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2013, 33, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nyquist, A.; Moser, T.; Jahnsen, R. Fitness, Fun and Friends through Participation in Preferred Physical Activities: Achievable for Children with Disabilities? Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2016, 63, 334–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, M.C.; Snider, L.; Prelock, P.; Kehayia, E.; Wood-Dauphinee, S. Children’s assessment of participation and enjoyment/preference for activities of children: Psychometric properties in a population with high-functioning autism. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 67, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoni, M.; Engel-Yeger, B.; Tirosh, E. Participation in leisure activities among boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 31, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullenhag, A.; Bult, M.K.; Nyquist, A.; Ketelaar, M.; Jahnsen, R.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Almqvist, L.; Granlund, M. An international comparison of patterns of participation in leisure activities for children with and without disabilities in Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands. Dev. Neurorehabil 2012, 15, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullenhag, A.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Granlund, M.; Almqvist, L. Differences in patterns of participation in leisure activities in Swedish children with and without disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Nova, F.; Oliveira, R.; Cordovil, R. Cross-Cultural Validation of Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment Portuguese Version. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuang, Y.; Su, C.Y. Patterns of participation and enjoyment in adolescents with Down syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riordan, A.; Kelly, E.H.; Klaas, S.J.; Vogel, L.C. Psychosocial outcomes among youth with spinal cord injury by neurological impairment. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2015, 38, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, J.P.; Lin-Ju, K.; Lisa, A.C.; Margo, O.; Donna, O.; Jill, M. Social and Community Participation of Children and Youth With Cerebral Palsy Is Associated With Age and Gross Motor Function Classification. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullenhag, A.; Almqvist, L.; Granlund, M.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L. Cultural validity of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment/Preferences for Activities of Children (CAPE/PAC). Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 19, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreault, M.; Belknap, K.; Lieberman, L.; Beach, P. Validation of Image Descriptions for the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment and Preferences for Activities of Children: A Delphi Study. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2022, 116, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches-Ferreira, M.; Alves, S.; Silveira-Maia, M. Translation, Adaptation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment / Preferences for Activities of Children (CAPE / PAC). J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2023, 16, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.; Leichtman, J.; Esposito, P.; Cook, N.; Ulrich, D.A. The participation patterns of youth with down syndrome. Front. Public. Health 2016, 4, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N.; Synnot, A.; Kearns, C. The extent, context and experience of participation in out-of-school activities among children with disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, D.O.; Cardoso de Sa, C.d.S.; de Lima Maciel, F.K.; Vila-Nova, F.; Gonçalves de Souza, M.; Guimarães Ferreira, R.; Longo, E.; Leite, H.R. I Would Like to Do It Very Much! Leisure Participation Patterns and Determinants of Brazilian Children and Adolescents with Physical Disabilities. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2023, 35, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikako-Thomas, K.; Shevell, M.; Schmitz, N.; Lach, L.; Law, M.; Poulin, C.; Majnemer, A. Determinants of participation in leisure activities among adolescents with cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 2621–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-y.; Li, C.-Y.; Huang, I.C.; Bendixen, R.; Chen, K.-L.; Weng, W.-C. Poster 7 The Cross-cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Evaluation of the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment-Chinese Version. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, S.; Waissman, P.; Diamond, G.W. Identifying play characteristics of pre-school children with developmental coordination disorder via parental questionnaires. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2017, 53, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreuer, N.; Sachs, D.; Rosenblum, S. Participation in leisure activities: Differences between children with and without physical disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badia, M.; Orgaz, M.B.; Verdugo, M.; Ullán, A.M. Patterns and determinants of leisure participation of youth and adults with developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2013, 57, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badia, M.; Orgaz-Baz, M.B.; Verdugo, M.A.; Martínez-Aguirre, M.M.; Longo-Araújo-de-Melo, E.; Ullán-de-la-Fuente, A.M. Adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the Leisure Assessment Inventory. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 50, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, M.; Orgaz, M.B.; Verdugo, M.; Ullán, A.M.; Martínez, M. Relationships between leisure participation and quality of life of people with developmental disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2013, 26, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calley, A.; Williams, S.; Reid, S.; Blair, E.; Valentine, J.; Girdler, S.; Elliott, C. A comparison of activity, participation and quality of life in children with and without spastic diplegia cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1306–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, G.; Karashima, C.; Uemura, J.I. Items Selection for the Japanese Version of the Preschool Activity Card Sort. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2020, 40, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dahab, S.M.N.; Alheresh, R.A.; Malkawi, S.H.; Saleh, M.; Wong, J. Participation patterns and determinants of participation of young children with cerebral palsy. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2021, 68, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, S.H.; Hamed, R.T.; Abu-Dahab, S.M.N.; AlHeresh, R.A.; Holm, M.B. Development of the Arabic Version of the Preschool Activity Card Sort (A-PACS). Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, T.B.; Silva, B.M.; Sousa, J.G.; Almeida, P.H.T.Q.d.; Davis, J.A.; Polatajko, H.J. Measuring children activity repertoire: Is the paediatric activity card sort a good tool for Brazilian therapists? Cad. Ter. Ocup. UFSCar 2016, 24, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, A.; Berg, C. Spanish Translation and Validation of the Preschool Activity Card Sort. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2008, 28, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.A.; Williams, M.T.; Olds, T.; Lane, A.E. Physical and sedentary activity in adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Yu, J.J.; Wong, S.H.S.; Sum, R.K.W.; Li, M.H.; Sit, C.H.P. The Associations Among Physical Activity, Quality of Life, and Self-Concept in Children and Adolescents with Disabilities: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 947336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajudeen, M.S.; Waly, M.; Manzar, M.D.; Alqahtani, M.; Alzhrani, M.; Alanazi, A.; Unnikrishnan, R.; Muthusamy, H.; Saibannavar, R.; Alrubaia, W. Physical activity questionnaire for older children (PAQ-C): Arabic translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and psychometric validation in school-aged children in Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- das Virgens Chagas, D.; Araújo, D.V.; Gama, D.; Macedo, L.; Camaz Deslandes, A.; Batista, L.A. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for older Children into a Brazilian Portuguese version. Hum. Mov. 2020, 21, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuberek, R.; Janíková, M.; Dygrýn, J. Adaptation and validation of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) among Czech children. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Baranowski, T.; Lau, W.P.; Chen, T.A.; Pitkethly, A.J. Validation of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) among Chinese Children. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2016, 29, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Ho, W.K.Y.; Khoo, S. The Chinese version of the physical activity questionnaire for adolescents: A psychometric validity, reliability, and invariance study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bervoets, L.; Van Noten, C.; Van Roosbroeck, S.; Hansen, D.; Van Hoorenbeeck, K.; Verheyen, E.; Van Hal, G.; Vankerckhoven, V. Reliability and Validity of the Dutch Physical Activity Questionnaires for Children (PAQ-C) and Adolescents (PAQ-A). Arch. Public Health 2014, 72, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggio, D.; Fairclough, S.; Knowles, Z.; Graves, L. Validity and reliability of a modified english version of the physical activity questionnaire for adolescents. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andarge, E.; Trevethan, R.; Fikadu, T. Assessing the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ–A): Specific and general insights from an Ethiopian context. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5511728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Diwan, S.J. Cross-cultural adaptation, translation, and psychometric properties of Gujarati version of physical activity questionnaire for older children. Physiother. -J. Indian Assoc. Physiother. 2020, 14, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makai, A.; Prémusz, V.; Dózsa-Juhász, O.; Fodor-Mazzag, K.; Melczer, C.; Ács, P. Examination of Physical Activity Patterns of Children, Reliability and Structural Validity Testing of the Hungarian Version of the PAQ-C Questionnaire. Children 2023, 10, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbi, E.; Elliot, C.; Varnier, M.; Carraro, A. Psychometric Properties of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children in Italy: Testing the Validity among a General and Clinical Pediatric Population. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isa, T.; Sawa, R.; Torizawa, K.; Murata, S.; Saito, T.; Ebina, A.; Kondo, Y.; Tsuboi, Y.; Fukuta, A.; Misu, S.; et al. Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2019, 13, 1179556519835833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Developing a Korean version of the physical activity questionnaire for older children. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2009, 3, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, N.A.M.; Sahril, N.; Omar, M.A.; Ahmad, M.H.; Baharudin, A.; Nor, N.S.M. Reliability and validity of the physical activity questionnaire for older children (PAQ-C) in Malay language. Int. J. Public Health Res. 2016, 6, 670–676. [Google Scholar]

- Wyszyńska, J.; Matłosz, P.; Podgórska-Bednarz, J.; Herbert, J.; Przednowek, K.; Baran, J.; Dereń, K.; Mazur, A. Adaptation and validation of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A) among Polish adolescents: Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdim, L.; Ergün, A.; Kuğuoğlu, S. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C). Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 49, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P.; Orr, K.; O’rourke, R.; Renwick, R.; Bruno, N.; Wright, V.; Bobbie, K.; Noronha, J. Quality of Participation Experiences in Special Olympics Sports Programs. Adapt. Phys. Activ Q. 2022, 39, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljenquist, K.; Kramer, J.; Rossetti, Z.; Coster, W. Content development, accessibility and feasibility of a self-report tool for use in programmes serving youth with cognitive disabilities: The Participatory Experience Survey. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2019, 66, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljenquist, K.; Coster, W.; Kramer, J.; Rossetti, Z. Feasibility of the Participatory Experience Survey and the Setting Affordances Survey for use in evaluation of programmes serving youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Feasibility of PES and SAS use in programme evaluation. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Batorowicz, B.; Rigby, P.; McMain-Klein, M.; Thompson, L.; Pinto, M. Development of a Measure to Assess Youth Self-reported Experiences of Activity Settings (SEAS). Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2014, 61, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batorowicz, B.; King, G.; Vane, F.; Pinto, M.; Raghavendra, P. Exploring validation of a graphic symbol questionnaire to measure participation experiences of youth in activity settings. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2017, 33, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, A.; Batorowicz, B.; Chrabota, U. Validation of the Polish version of the Self-reported Experiences of Activity Settings (SEAS) questionnaire. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 23, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M. Test-retest reliability. Encycl. Meas. 2007, 1, 993–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, E.; Badia, M.; Orgaz, B.; Fechine, C. Experiences in the participation of leisure activities: A qualitative study using the focus group method to obtain the perspectives of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- King, G.; Petrenchik, T.; Law, M.; Hurley, P. The Enjoyment of Formal and Informal Recreation and Leisure Activities: A comparison of school-aged children with and without physical disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2009, 56, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartermaine, J.R.; Rose, T.A.; Auld, M.L.; Johnston, L.M. Reflections on Participation at Home, As Self-Reported by Young People with Cerebral Palsy. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2024, 27, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilgour, G.; Stott, N.S.; Steele, M.; Adair, B.; Hogan, A.; Imms, C. More than just having fun! Understanding the experience of involvement in physical activity of adolescents living with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 3396–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, B.; Ullenhag, A.; Keen, D.; Granlund, M.; Imms, C. The effect of interventions aimed at improving participation outcomes for children with disabilities: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2015, 57, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, C.; Carswell, A. Individualized Outcome Measures: A Review of the Literature. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2002, 69, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkerk, G.J.; Wolf, M.J.M.; Louwers, A.M.; Meester-Delver, A.; Nollet, F. The reproducibility and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in parents of children with disabilities. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenbeek, D.M.D.; Ketelaar, M.P.; Lindeman, E.M.D.P.; Galama, K.O.T.; Gorter, J.W.M.D.P. Interrater Reliability of Goal Attainment Scaling in Rehabilitation of Children with Cerebral Palsy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, G.; Auld, M.L.; Johnston, L.M. SPORTS STARS study protocol: A randomised, controlled trial of the effectiveness of a physiotherapist-led modified sport intervention for ambulant school-aged children with cerebral palsy.(Report). BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedman, S.E.; Boyd, R.N.; Elliott, C.; Sakzewski, L. ParticiPAte CP: A protocol of a randomised waitlist controlled trial of a motivational and behaviour change therapy intervention to increase physical activity through meaningful participation in children with cerebral palsy. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, G.; Gent, M.; Thomson, D. It takes a ‘spark’. Exploring parent perception of long-term sports participation after a practitioner-led, peer-group sports intervention for ambulant, school-aged children with cerebral palsy. JSAMS Plus 2025, 5, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assessment Name | Participation Component | Included Studies | Administration (Mode, Time) | Target Population | Cultural Adaptations | Cost (AUD) | Sport/Physical Recreation Items (%) | Relevant Subscales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessments of attendance and involvement | ||||||||

| Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) [64] | Attendance (Frequency and Diversity) Involvement (Enjoyment) | [54,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] | Self/parent-administered or interview 30–45 min | 6–21 years, non-disabled or people with physical or intellectual disability | Arabic [65], Brazilian Portuguese [98], Chinese [100], Dutch [69], German [72], Greek [66], Norwegian [83], Portuguese [89,95], Spanish [80], Swedish [93] | $289 (Test kit and forms) | 27% (15/55 items) | Active physical (9/13 items) Skill-based (5/10 items) |

| Assessments of attendance | ||||||||

| Children’s Leisure Assessment Scale (CLASS) [55] | Attendance (Frequency and Diversity) | [55,101,102] | Self-administered 15 min | 10–18 years, non-disabled or people with physical or intellectual disability | Developed in Hebrew [55] | No Cost (on request from authors) | 23% (7/30 items) | Games and Sports (3/5 items) |

| Leisure Assessment Inventory (LAI) [56] | Attendance (Diversity) | [103,104,105] | Interview 45 min | >30 years, non-disabled or people with ID | Spanish [104] | $337 (Test kit and forms) | 31% (16/52 items) | No relevant subscale |

| Paediatric Activity Card Sort (Pre-ACS) [57] | Attendance (Frequency and Diversity) | [106] | Parent interview 30–60 min | 5–14 years, non-disabled or people with physical or intellectual disability | Japanese [107] | $134 (Test kit and forms) | 24% (18/75 items) | Sports (12/12 items) |

| Preschool Activity Card Sort (PACS) [58] | Attendance (Diversity) | [58,108] | Parent interview 30–60 min | 3–6 years, non-disabled or people with ID | Arabic (95 activities) [109], Brazilian Portuguese [110], Spanish [111] | $70 (Test kit and forms) | 19% (16/85 items) | High physical demand leisure (9/12 items) |

| Physical Activity Questionnaire (PAQ) for Older Children or Adolescents [59] | Attendance (Frequency and Diversity) | [9,112,113] | Self-administered 20 min | 8–14 years (PAQ-C) 14–19 years (PAQ-A) | Arabic [114], Brazilian Portuguese [115], Czech [116], Chinese [117,118], Dutch [119], English [120], Ethiopian [121], Gujarati [122], Hungarian [123], Italian [124], Japanese [125], Korean [126], Malay [127], Polish [128], Turkish [129] | No Cost | 88–90% (8/9–10 items) The PAQ-A removes one question relating to ‘recess’. | No relevant subscale |

| Assessments of involvement | ||||||||

| Measure of Experiential Aspects of Participation (MEAP) [60] | Involvement (Autonomy, Belongingness, Challenge, Engagement, Mastery, Meaning) | [60,130] | Self-administered Time not reported | >19 years, people with physical disability | None identified | No Cost | 100% (context dependent) | No relevant subscale |

| Participatory Experience Survey (PES) [61] | Involvement (Environment, Skill Development, Experience) | [131,132] | Interview 3 min | 14–22 years, people with intellectual disability | None identified | No Cost | 100% (context dependent) | No relevant subscale |

| Self-reported Experiences of Activity Settings (SEAS) [133] | Involvement | [133,134,135] | Self-administered Time not reported | 13–23 years, non-disabled or people with physical or intellectual disability | Polish [135] | No Cost | 100% (context dependent) | No relevant subscale |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Clutterbuck, G.L.; Wen, E.; Petroccitto, S. Assessment of Sport and Physical Recreation Participation for Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040557

Clutterbuck GL, Wen E, Petroccitto S. Assessment of Sport and Physical Recreation Participation for Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040557

Chicago/Turabian StyleClutterbuck, Georgina Leigh, Eugeenia Wen, and Sara Petroccitto. 2025. "Assessment of Sport and Physical Recreation Participation for Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040557

APA StyleClutterbuck, G. L., Wen, E., & Petroccitto, S. (2025). Assessment of Sport and Physical Recreation Participation for Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040557