Abstract

The “Baby Ubuntu” programme is a well-established, low-cost, community-based intervention to support caregivers of children with complex neurodisability, like cerebral palsy, in low- and middle-income country (LMIC) contexts. This process-focused paper describes our utilisation of the ADAPT guidance to adapt “Baby Ubuntu” for use in ethnically and linguistically diverse, and economically deprived urban boroughs in the United Kingdom (UK). The process was guided by an adaptation team, including parents with lived experience, who explored the rationale for the intervention from local perspectives and its fit for this UK community. Through qualitative interviews and co-creation strategies, the perspectives of caregivers and healthcare professionals substantially contributed to the “Encompass” programme theory, drafting the content, and planning the delivery. Ten modules were co-produced with various topics, based on the “Baby Ubuntu” modules, to be co-facilitated by a parent with lived experience and a healthcare professional. The programme is participatory, allowing caregivers to share information, problem solve, and form supportive peer networks. The “Encompass” programme is an example of a “decolonised healthcare innovation”, as it aims to transfer knowledge and solutions developed in low- and middle-income countries to a high-income context like the UK. Piloting of the new programme is underway.

1. Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) refers to a group of disorders caused by an injury to the developing brain that affects movement, posture, and muscle tone [1]. It is the most common cause of a physical childhood-onset disability, affecting 1 in 400 births in the United Kingdom (UK) [2]. These difficulties result in functional limitations as well as participation and activity restrictions [3]. Children with CP often present with numerous additional conditions, which require a multi-disciplinary team approach [4]. As a result, their parents and primary caregivers are required to manage the multiple services and professionals involved, which can be overwhelming and result in feelings of stress, guilt, and inadequacy [5]. A disproportionate number of healthcare services are involved in their care, along with services from social care, education, and charity sectors [6,7]. The high frequency of medical appointments among children with CP is not only attributed to their co-morbidities, but also to inadequately coordinated and integrated health services [8], an issue that becomes more pronounced during adolescence and adulthood [9]. In this paper, we use the term “caregivers” to inclusively refer to parents, relatives, and others who provide primary care for the child.

Receiving a diagnosis like CP is a life-altering moment for caregivers, as they face multiple challenges in caring for their child, their family, and themselves [5]. Simultaneously, they are learning to cope with the grief of losing their envisioned future, accepting their child’s disability, dealing with their own emotions, and juggling a deluge of appointments that arrive on their doorstep [10]. Caregivers of children with complex neurodisability, such as CP, consistently present with adverse health outcomes such as increased levels of depression, anxiety, and musculoskeletal disorders [11,12,13]. Factors contributing to these health challenges include: a lack of understanding from friends and family, feelings of isolation, a lack of knowledge, financial worries, the physical challenges of moving and handling their child and dealing with the continuous cycle of challenges [11,14,15].

The difficulties faced by caregivers of children with CP are further exacerbated in the ethnically and linguistically diverse, and economically deprived urban areas of East London in the UK, where this study is based. These areas experience significantly higher rates of children living in poverty, along with increased mental and physical health issues, and higher service use compared to the rest of the UK [16,17,18]. They also have reduced health literacy [19] and a low proportion of first-language English speakers [20].

1.1. Family-Centred Care

Family-centred care, the gold standard approach to delivering healthcare for children with complex conditions, requires working together in partnership with caregivers to support the unique and individual needs of each child and family [21,22]. Family-centred care describes an approach to decision-making between the family and health professional with principles including information sharing, respecting and honouring differences, partnership and collaboration, negotiation, and care within the family and community context [23]. However, a gap remains in our understanding and ability to deliver family-centred care, particularly in diverse urban settings with increased levels of child poverty [18], low rates of health literacy [19], and reduced wellbeing of the population [16,17]. These challenges present additional barriers to accessing health and social care services and increase the health inequalities experienced by families of children with complex neurodisability. Our recent qualitative study conducted in East London (UK) highlighted the mental health challenges experienced by caregivers of children with complex neurodisabilities, the lack of provision of knowledge about their child’s condition, and the disjointed care that they experience while attempting to juggle multiple services, each with its own jargon and language [24]. The “Ubuntu Hub” has been highlighted as a source of evidence-based, low-cost programmes to improve the provision of appropriate family-centred support for families of children with complex neurodisability in the UK [25].

1.2. The Ubuntu Hub

The Ubuntu Hub is a non-profit shared learning and research hub providing participatory programmes of care and support for children with developmental disabilities and their caregivers, rooted in the African philosophy of ‘Ubuntu,’ which champions community and shared humanity and based on the principles of adult learning theory [26] and family-centred care. Programme goals are to promote inclusion and participation of children with disabilities, support developmental progress, understand and respond to the lived experience of caregivers, and promote caregiver agency through accessible information, skills building, and peer support. Originally developed from “Getting to Know Cerebral Palsy”, the Hub now includes several programmes for use in a wide range of contexts. These include “Baby Ubuntu” for children 0–3 years [27], Ubuntu Kids for children 2–12 years [28], Juntos [29,30] for children with congenital Zika syndrome, and Obuntu Bulamu for inclusive primary education [31].

Mixed methods evaluations of the Ubuntu Hub programmes have demonstrated improvements in caregiver wellbeing and confidence in caring for their child, increased peer support, improved child development, behaviour, and wellbeing, and greater understanding and attitudes towards children with disabilities [28,29,30,31]. The “Baby Ubuntu” feasibility trial in Uganda showed the programme to be low-cost, feasible, and acceptable from the perspective of the families and providers, in both urban and rural settings [27] and pre-/post-evaluations have reported a 20–25% improvement in family impact quality of life [32]. A single-blind, effectiveness implementation–hybrid (type II) cluster randomised trial of the “Baby Ubuntu” programme integrated with government health services in Rwanda is currently underway [33]. To date, the Ubuntu programmes are being implemented across 13 countries, including East and West Africa, South America, and more recently in India and Guatemala; however, no formal adaptation for high-income countries (HICs) as yet exists.

1.3. Frugal Innovations in the UK

Although there has been a recent steer towards considering low-cost or ‘frugal’ health innovations for HICs like the UK and US [34,35], there are barriers to this in practice. There is an unconscious bias that the ‘correct’ direction of knowledge transfer flows from HICs to LMICs [36]. Furthermore, global research and innovation are skewed towards the West [37]. Even the term ‘reverse innovation’, which describes the adoption of innovations developed in LMICs for HICs, reiterates the direction that the concept is attempting to dismantle [38]. A low-cost innovation that solves a problem for a community might be just as likely to be needed in a context, such as the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), which is currently facing increased pressures and a workforce crisis [39]. The NHS has seen an increase in the adoption of frugal technologies, particularly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, there has been encouragement to consider these innovations beyond times of crises [40]. A higher-cost solution is unlikely to be feasible, acceptable, or solve challenges in the under-resourced and pressured context of the NHS. The bi-directional flow of innovations between settings and the adoption of frugal innovations by the NHS are increasingly important when solving implementation problems [36], such as the challenges documented above in providing family-centred care for children with complex neurodisability.

This paper reports on the process used to adapt a low-cost innovation (the Ubuntu programme) developed in LMICs into ethnically and linguistically diverse, and economically deprived areas within a HIC (the UK).

The adaptation process aimed to address the following questions:

- What should the content of the new programme be? What should the adapted content look like?

- How should the adapted programme be delivered in the new context?

- How can the new programme best reach diverse and underserved populations in the London boroughs?

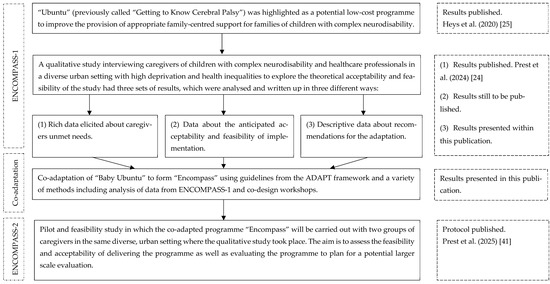

This paper describes the steps taken to adapt the “Baby Ubuntu” caregiver group support programme. The new programme (re-named “Encompass”) and its structure are described along with the logic model describing how the programme is expected to work. Please refer to Figure 1 to understand how this publication fits into the wider programme of work.

Figure 1.

An overview of the different studies involved in ‘ENCOMPASS’ [24,25,41].

2. Methods

The programme was adapted using the ADAPT framework [42] with results presented based on recommended reporting items.

The adaptation process involved:

- The formation of an adaptation team.

- Exploring the rationale for the intervention from local perspectives.

- Exploring the intervention fit of “Baby Ubuntu” for East London, UK.

- Gathering recommendations from local caregivers and healthcare professionals on the content and delivery of the intervention and how to reach diverse populations.

- Drafting the adapted programme manual and programme theory.

Further information about how the ADAPT process items were operationalised may be found in Appendix A.1. Although implementation data is not yet available, a pilot and feasibility study [41] is currently underway with results to be shared in a future publication.

2.1. Adaptation Team

The adaptation team was formed at the beginning of the project. It consisted of the core research group (PhD student K.P. and four supervisors A.H., M.H., K.B., C.H.) as well as caregivers with lived experience (A.J., K.T., M.C., R.O.). There were also health professionals and academic researchers who were involved in the original development of the “Baby Ubuntu” programme and subsequent implementation and adaptations in LMICs (C.J.T., R.L., T.S.). Finally, there were professionals on the team with expertise in relation to the clinical population, the development, and evaluation of complex interventions, and the NHS/UK context (C.M., E.W., P.H., A.B., F.B.).

The adaptation team met every 6 months to explore key uncertainties, share local perspectives, develop the programme theory, and make decisions about the programme manual and delivery plan.

The parents with lived experience included four mothers (A.J., K.T., M.W., R.O.) who were recruited through two community child health centres and by word of mouth from other parents. Attempts were made to attract a diverse group of caregivers who could represent a variety of perspectives. No fathers put themselves forward. Although the mothers formed a diverse group of ages, ethnicities, and cultures, they shared resemblances in their journeys of being mothers of adolescents/young people with complex neurodisability. It was made clear from the beginning that this would not be a one-off project and that the group could continue to meet formally or informally after this study ended. The Involvement Matrix tool [43] was utilised at initial meetings as a way of promoting a more equitable power structure. Their contributions and expertise are acknowledged through co-authorship [44]. The adaptation team members who were involved in the original development of the “Ubuntu” programme (C.J.T., R.L., T.S.) provided answers to questions around uncertainties (e.g., characteristics of the venue required), offered useful tips for the adaptation process (e.g., recording essential decisions made with regard to the content development and delivery plan with clear justifications), and stimulated discussion around context (e.g., conceptualising Uganda’s health system in relation to non-profit organisations, in comparison to the UK’s government-funded health system which better reflects implementation of “Baby Ubuntu” in Rwanda).

These parents with lived experience initially met separately with K.P. to build their confidence in becoming co-creators [45] and to ensure their voices were heard. Once they felt more confident, they joined the larger adaptation group meetings to share their perspectives with the wider team. The professionals in the adaptation team were experienced in partnering with families in research and were, therefore, conscious of the power imbalances. Every attempt was made to create an inclusive culture within these meetings that valued expertise through experience as much as professional knowledge. K.P. facilitated these meetings, and efforts were made to ensure that every person had an opportunity to be heard. Debrief sessions also took place with the parent partners after the meetings, if required.

2.2. Local Perspectives

We conducted a qualitative interview study to explore local perspectives relating to processes 2–4 in the ADAPT framework (see above). These included exploring (2) the rationale for the intervention, (3) the intervention fit, and (4) local recommendations for the new programme manual and delivery plan. Figure 1 shows the results from the qualitative study that have been reported in this paper.

Twelve caregiver participants were recruited from an inner-city area in East London, UK, that is ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse, with high levels of poverty. Most were mothers (n = 10) with ages ranging from 31 to 42 years. There were variations in ethnicity, accommodation types, employment status, and state benefits received. Their children’s ages ranged between 2 and 15, and most had a diagnosis of cerebral palsy with varying levels of impairment. Detailed information relating to participant characteristics and recruitment procedures has been reported in the publication outlining the local unmet needs of those caring for children with complex neurodisability (first set of results from the qualitative study, as seen in Figure 1) [24]. These results were triangulated with existing evidence confirming that caregivers of children with complex neurodisability require comprehensive, jargon-free information about their child and available services, support for their own wellbeing, and more joined-up working between health services. This provided much of the rationale for the intervention in this context (ADAPT framework process 2).

Two rounds of semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants, the second round being important for the aims and research question for this paper. Participants were shown a presentation about the “Ubuntu” programme and asked general questions about the content, format, and ways to reach diverse groups. Subsequently, questions were asked about each module; for example, ‘Is this module important?’, ‘What additional information would be important to include?’ and ‘What information is not relevant to parents/carers in the UK?’ Interpreting services were offered for those who required them.

Six healthcare professionals working with children with complex neurodisability from the same community child health centre were interviewed in the same way and asked for their opinions and recommendations. Disciplines included health visitors (n = 2), occupational therapist (n = 1), paediatrician (n = 1), physiotherapist (n = 1), and a speech and language therapist (n = 1).

Interviews were conducted online, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Content analysis using NVivo software was used to summarise the data on recommendations for ‘content’, ‘delivery’ and ‘reaching diverse populations’. In this way, the fourth step of the ADAPT framework process was followed by gathering specific recommendations from local caregivers and healthcare professionals in the community relating to the content, delivery, and how to reach diverse populations.

2.3. Exploration of the Context–Intervention Fit

The ADAPT guidance encourages researchers to compare the previous context and the new context, focusing particularly on the similarities between the two [42]. The two settings (Kampala and Kiwoko, Uganda and East London, UK) were compared in site visits by K.P. in discussion with the wider team and through conversations with caregivers and healthcare professionals in each. In exploring the contexts, it would be naive to overlook the political history of coloniality between Britain and Uganda, recognising the historical extraction of resources and exploitation of their people. The traditional direction of knowledge flow was from Britain (the coloniser) to Uganda (the colonised), and it is important to acknowledge the discomfort some may face in the recognition of similarities, such as seeing the NHS as a low-resource health system [36]. Recognising these similarities challenges the notion that people accessing healthcare in Uganda bear no resemblance to those accessing care in the NHS, UK. It presents a new perspective to look beyond the broad-brush strokes of differences between settings, such as ethnicity or economic status, and towards an understanding that resemblance between populations or settings can be nuanced and subtle. For example, it has been made clear that within the context of having a child with a complex neurodisability, regardless of nationality, ethnicity, socio-economic status, or language, parents and caregivers face challenges to their wellbeing [46,47,48,49,50].

2.4. Development of the Programme Manual and Programme Theory

We co-created the “Encompass” programme manual through several iterative cycles of adaptation from “Baby Ubuntu”. The ten modules were agreed upon by the adaptation team based on feedback from the qualitative interviews. The parents with lived experience on the adaptation team then advised on the content of the modules to ensure the pictures, texts, and examples provided were appropriate and sensitive to their context and target population. These decisions were explored during workshops through mind mapping, discussion, and paper-based technologies, alongside emails and electronic comments in between workshops/meetings. Further comments and suggestions were collected when the facilitators were trained, and feedback was sought on the manual content. All changes were made by the lead researcher (K.P.) after each workshop and meeting. Plans for delivery were brought to the adaptation team meetings and discussed until consensus was reached. The parents with lived experience advised on key delivery decisions, such as devising a job description for the facilitators and how to reach underserved groups in recruitment. Any differing views between professionals and caregivers were discussed during adaptation, with current evidence and caregivers often given greater power for decision-making. Appendix A.2 includes a summary table linking feedback to specific adaptation decisions.

The programme theory was developed using a realist methodology to describe the impact of the “Encompass” groups using context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations. This methodology is a theoretically underpinned, pragmatic approach that explores how interventions work, in what circumstances and for whom, rather than only focusing on whether they work or not [51,52]. Realism lies between the positivist lens, where context is seen as a source of bias, and the social constructionist lens, where context is viewed as a foundation of knowledge. For this project, context is therefore described as the interactions between systems, relationships, the way people assign meaning, and the implicit rules that govern how people respond, which all impact the outcomes [53]. It refers to the conditions in the background that would influence the outcomes of the programme. Mechanisms refer to the unseen resources and responses that cause the effects (or outcomes) of the programme through interacting with the context [51]. The mechanisms are based on the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) taxonomy (v1) [54] and the interpersonal change processes from the Mechanisms of Action in Group-based Interventions (MAGI) framework [55]. The BCTs are helpful in providing a common language to describe processes within the programme that aim to change the behaviour of the participants [54]. The MAGI framework provides an additional understanding of how the intricacies of a group-based intervention may influence change within the participants [55]. Outcomes may be intended or unintended based on the interaction between the context and mechanisms [51].

The programme theory was developed with input from the adaptation team, with realist evaluation principles guiding discussion about how caregivers would respond to elements of the “Encompass” programme within their context to achieve the expected outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Context–Intervention Fit

Similarities and differences between the two settings (Kampala and Kiwoko, Uganda and East London, UK) are illustrated in Table 1. The differences influenced the adaptation process as they informed decisions about removing content (e.g., related to traditional healers) and adding content (e.g., about the UK schooling system and available equipment for the children). The similarities and differences described in Table 1 relate primarily to the experience of raising a child with a disability and the challenges that accompany this. Many of these experiences are similar; however, there are large structural differences that cannot be ignored, such as the poverty experienced by many in Uganda and the limited access to appropriate healthcare, education, transportation, and housing compared to the UK. Programmes like “Baby Ubuntu” are, therefore, developed within these resource-constrained systems using approaches that are participatory, community-based, low-cost, and often peer-led. It is these types of innovations and approaches developed in LMICs as a response to structural difficulties that may be useful for adoption in HICs.

Table 1.

Similarities and differences between settings for “Baby Ubuntu” (Kiwoko, Kampala and other parts of Uganda) and “Encompass” (East London, UK).

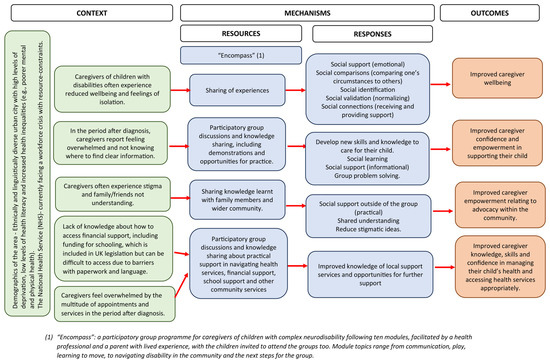

3.2. The Programme Theory

The programme theory produced by the adaptation team for “Encompass” is depicted in a logic model using CMO configurations (Figure 2). Example outcomes are improved wellbeing, empowerment, advocacy, confidence, or knowledge and skills.

Figure 2.

The encompass logic model illustrating the programme theory. The blue-filled boxes indicate the mechanisms of the programme. “Encompass” is briefly described, followed by specific resources offered through the programme. Examples of mechanisms are the sharing of information during the “Encompass” groups (resources) and improved social support, connections, and validation (responses). An example BCT component (and mechanism) is problem-solving within the group, which aims to change the caregiver’s level of confidence and empowerment (the behaviour change/outcome). An example of a MAGI framework component is social validation. Interacting with others in the group in similar situations, caregivers may feel that their own situation is normalised (mechanism), which may have an effect on their wellbeing (an outcome).

The green-filled boxes indicate the context, which ultimately represents the experience of being a caregiver of a child with a complex neurodisability in a society that is not set up for families to participate fully in all areas of life, with the appropriate care and understanding in place. Aspects of the specific setting within the context are described too, such as the NHS facing a workforce crisis and the demographics of the area in which the programme takes place.

The orange-filled boxes represent the anticipated outcomes based on the interactions between the mechanisms and the context. These outcomes will be explored in a pilot and feasibility study [41].

3.3. The “Encompass” Programme

The “Ubuntu” manuals and materials can be copied or adapted to meet local needs; they may be distributed if they are free or not for profit. From its conception, “Ubuntu” has, therefore, been made available with an explicit culture of openness and collaboration attached to it. The “Ubuntu” programme itself has undergone many adaptations because of researchers and organisations sharing resources and ideas, which has then paved the way for projects such as “Encompass” to continue in the spirit of collaboration and adaptation. There were, however, certain core values of the programme that were non-negotiable, such as having a parent with lived experience as one of the facilitators, and ensuring the groups were participatory, including learning from each other rather than module content being ‘taught’. In the current adaptation, two of the modules were merged, with a new module on schools included. However, most of the manual remained the same, with specific activities adapted according to local needs.

3.4. Delivery Plan

The co-adapted delivery plan for “Encompass” has been described below in Table 2, using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) [56] checklist, along with elements from the checklist for reporting of group-based behaviour-change interventions [57]. Illustrative quotes are provided when appropriate from the qualitative study referenced in Figure 1 (C = caregiver, H = healthcare professional). Final decisions were made during co-production workshops with the parent partners with lived experience and during meetings with the wider adaptation team.

Table 2.

Description of elements of the “Encompass” programme using the checklist for group-based behaviour-change interventions and the TIDieR checklist.

Most of the delivery plan remains similar to “Baby Ubuntu”; however, a few key adaptations were made. These included shortening the length of sessions to make it more feasible for families to attend and reducing the number of sessions (through removing and/or combining modules). An online or hybrid option was considered but ultimately decided against based on feedback from the adaptation team.

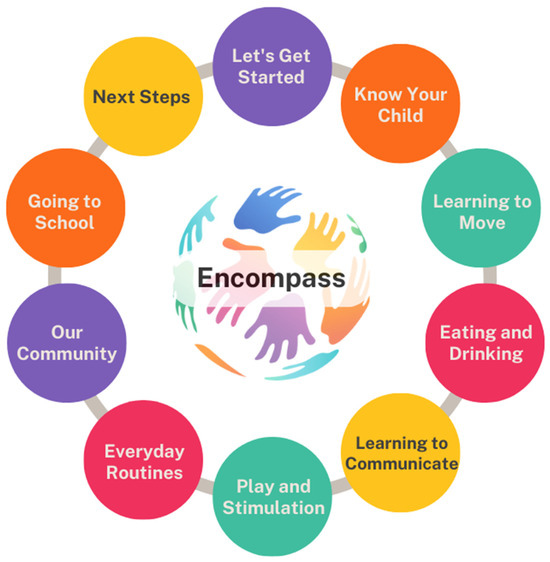

3.5. Content

There was consensus from the caregivers and healthcare professionals in the qualitative study that the “Baby Ubuntu” modules were of relevance to their setting in East London, UK. The modules for “Encompass” are therefore based on the “Baby Ubuntu” modules, with adaptations made based on feedback from the qualitative study referenced in Figure 1. Many of the pictures and activities in the manual were changed to be culturally sensitive to the ethnically diverse urban UK populations.

See Figure 3 below for the “Encompass” modules, followed by Table 3 which provides detailed descriptions of each session and the rationale for adaptations made.

Figure 3.

The “Encompass” programme modules [41].

Table 3.

Description of “Encompass” modules and adaptations made from “Baby Ubuntu” modules.

A potential additional module was raised during the qualitative interviews around the topic of caregivers looking after themselves, particularly focusing on mental health. There was consensus, however, that this could be interwoven into each module and caregivers could be signposted to programmes, such as the Healthy Parent Carers [59], where the focus is solely on taking care of their own wellbeing.

3.6. Reaching Diverse Populations

Participants in the qualitative study were asked questions around how to reach underserved groups of caregivers, how to account for different languages, and how to consider grouping such a clinically heterogeneous group of children.

A strong recommendation that emerged from most interviews was to consider the atmosphere of the groups. This included suggestions such as ensuring no medical jargon was used throughout the programme, making it a welcoming environment, having refreshments available, having a safe space to share experiences, but being mindful that some may not be ready to speak, and focusing on relationship building between the group members and facilitators.

“But if they don’t feel comfortable [to share], you shouldn’t pressure them into saying, oh, tell us about your story or tell us your experience if you want. If they don’t then they just enjoy learning about the rest. As long as they’re comfortable.”C15

“I think some people won’t want to share their personal stories. But I guess once they meet up more and they become more comfortable with each other they may be able to start sharing.”C3

Group rules or guidelines were recommended to be developed together at the initial group meeting with the assistance of the facilitators. Examples for this included respecting others’ opinions, listening to each other, using mobile phones on silent, and confidentiality (while understanding the limits in relation to disclosure of harm or risk). The above recommendations relate to the best ways of serving diverse groups of caregivers once they have agreed to participate. Examples of how to reach individuals before this stage included making it explicit that interpreting services would be available, advertising where different cultural groups congregate and in public areas and using a variety of paper-based and social media methods.

There was a lack of consensus and uncertainties about grouping together children who may have vastly different clinical presentations and severity of impairments. Some felt that caregivers could gain more from the group if they were grouped with similar children, and healthcare professionals would be able to facilitate practical sessions around positioning with more ease.

“I wouldn’t want to discuss my son with somebody whose child can’t even speak or needs to be fed. I would as a parent feel slightly awkward or uncomfortable because I don’t understand what they’re going through.”C16

“Diverse groups allow you to learn a little bit, but you can probably learn more if you have children of similar abilities.”C15

Others in the study thought that this may make others feel excluded. The decision ended up being a pragmatic one, as there would not be enough participants to group children according to their abilities. During the facilitator training, discussions will be had on how to manage having a group of families who have children with differing abilities, how to create a supportive and inclusive environment, and how to encourage sharing of experiences. This is, however, an uncertainty that should be further explored in the pilot and feasibility study.

Similar views were reported for grouping caregivers according to the language spoken to reduce the amount of time required for various interpreters. However, the same pragmatic decision was made to go ahead with inclusive, diverse groups and explore this issue further in the feasibility and pilot study.

4. Discussion

This paper describes the process of adapting the “Baby Ubuntu” programme developed in Uganda to form “Encompass” for the UK. It provides details on the programme theory, delivery plan, and modules of “Encompass”. The programme theory was developed using a realist framework and depicted in a logic model using context–mechanism–outcome configurations. Core elements of the delivery plan were kept, including having a parent with lived experience as a facilitator, and the groups needed to follow a participatory approach. Minor adjustments were made regarding the length and frequency of groups, and it was decided that home visits were not required in this population, as the families received enough support from therapists and other health professionals. It was decided that groups would be held in person, but that online optionality should be explored in the future. Most of the module content remained the same, with minor adjustments made based on local needs. However, one new module was developed, ‘Going to School’. The “Encompass” adaptation is novel in that it is the first time the “Ubuntu” programme has been adapted for a high-income country.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The strength of the co-adaptation process lies in the participation of those with lived experience being involved in the key decision-making aspects of the “Encompass” programme. Principles from Albert and colleagues [60] describe the importance of efforts shown to shift power and the willingness to share it, to draw from diverse sources, to go to communities rather than expecting them to come to you, and to aim for long-term relationship building rather than short-term. The group of parents with lived experience met in a local community library or online, depending on what was more convenient for them. It was made clear from the beginning that this would not be a one-off project and that the group could continue to meet after this study ended. Parents from this group held greater power in decision-making as their local, lived experience allowed them to provide highly relevant expertise for their context. It is, however, a limitation that only mothers with lived experience were involved in the adaptation team. For future studies relating to this programme, efforts will be made to engage fathers and other under-represented caregivers through community organisations, health professionals, and word of mouth from participants who attended the pilot groups.

Another strength of this study is the systematic approach taken, which involved combining both participatory and theory-based elements in the process. Data from the qualitative study, another key recommendation for adaptation studies [61], were considered alongside the perspectives of the adaptation team to inform decisions around the content, delivery, and how to reach and support diverse and underserved families. The inclusion of key members who were involved in the development and adaptations of “Ubuntu” and “Baby Ubuntu” allowed for valuable knowledge to be shared about previous learnings. The adaptation team did not need to rely solely on publication materials to fully understand the implementation of “Baby Ubuntu”, as queries could be raised with the team themselves.

It is important to note the limitations of the project, particularly when the contexts of Uganda and the UK were contrasted to explore the similarities and differences. Firstly, context is not a ‘thing’ to be researched (a noun), but rather something that ‘happens’ and that researchers ‘do’ (a verb) [62]. Context is complex and dynamic, and interacts with every part of an intervention. The decisions made in this project were guided by observations and discussions at the time, with an understanding that people and places cannot always be simplified and generalised. The descriptions of the similarities and differences between settings described in Table 1 were understood through the lens of the first author (K.P.), a South African, white female currently residing in the UK. KP brings her own experiences of working in low-resource settings in South Africa and the NHS, along with an understanding of her own privilege and how that shapes others’ interactions around her. How the first author made sense of context and its influence on the content of Table 1 might be different for another researcher.

4.2. Wider Generalisability

The adaptation followed a similar process to the creation of “Juntos”, an adaptation of the “Ubuntu” programme for families of children with Congenital Zika Syndrome in Brazil [30]. In both the “Juntos” and “Encompass” adaptations, a needs analysis was conducted, and advisory groups were established to support decision-making and the development of the manual. Both programmes developed a theory of change/programme theory to anticipate the mechanisms and impact. Both decided to pilot the groups co-facilitated by an expert parent and a therapist. The “Juntos” manual integrated a new component relating to caregiver emotional wellbeing by providing prompts at the end of each session, and this was incorporated into the “Encompass” manual. Although each programme was adapted for a different context and to support families of children with varying needs, the adaptation and delivery processes followed a similar approach. This suggests that the adaptation model may be transferable to other settings and populations.

The co-adaptation of “Baby Ubuntu” to form the “Encompass” programme is an example of a ‘decolonised healthcare innovation’ [36], as the programme was developed and implemented in LMICs and considered to be a potential frugal innovation for a resource-constrained setting in the UK. ‘Decolonisation’ in global health aims to dismantle ideas about health often created by those with the greatest power [63], thus moving away from a ‘top-down’ approach where the knowledge is most valued from those who have historically held power. The adaptation described in this paper not only values the knowledge created by the Ubuntu Hub teams in LMICs but also the expertise brought by those with lived experience. Using a community-based, participatory, peer-led approach in the co-design, adaptation and implementation of these programmes challenges the dominant discourse that only HICs can generate high-quality research and innovations. It needs to be acknowledged that using the word ‘decolonisation’ as a metaphor can be problematic when it does not explicitly relate to the repatriation of indigenous land and life [64]. We hope, however, that this example may stimulate consideration of other frugal innovations to be co-adapted in child health research, looking beyond the traditional ideas that LMICs are ‘too different’ to consider transferability of findings. Research has demonstrated that interventions, which have been carefully adapted, are more likely to succeed than those adopted or transported between settings without consideration of culture and context. For example, the Africa Clubfoot Training, developed with the University of Oxford, was the first standardised training programme for clubfoot treatment [65,66]. It has since been adapted for use in the UK and other high-income training environments and is accredited by the Royal College of Surgeons in England [67].

4.3. Implications and Further Research

The qualitative study conducted with caregivers and healthcare professionals in East London provided preliminary evidence on the theoretical feasibility and acceptability of implementing a co-adapted version of “Baby Ubuntu”, which was further explored during the co-adaptation process of forming “Encompass”. Uncertainties remain, which have implications for further research. Bonell and colleagues [68] recommend piloting implementation when there are uncertainties around the feasibility of delivering an intervention. These implementation uncertainties will, therefore, be explored in the pilot and feasibility study [41]. Whether the implementation of “Encompass” will trigger the intended mechanisms and outcomes, according to the programme theory, will also need to be explored in a larger evaluation of effectiveness.

5. Conclusions

“Encompass” is a participatory group programme for caregivers of children with complex neurodisabilities that aims to improve the skills, knowledge, and confidence of caregivers as an example of the implementation of family-centred care. The process of adaptation highlighted the remarkable similarities between the content and delivery plan in both settings (Uganda and the UK). This demonstrates that there is more to ‘context’ than the apparent observable differences (e.g., culture, language, health systems, infrastructure) and that the shared experience of raising a disabled child may surpass these. One of the aims of describing the co-adaptation process is to improve the reporting of adaptation processes, particularly given that this example describes a low-cost innovation developed in low- and middle-income countries being adapted for the first time to a high-income country. Although the results may provide utility to groups interested in the research and implementation of “Encompass”, it is the methods which may be of interest to others and could be replicable in a plethora of contexts.

Author Contributions

K.P., A.H. and M.H. conceptualised the paper and were involved in funding acquisition. The methodology was developed by K.P., A.H., M.H., K.B., C.H., A.B., P.H., R.L., C.M., T.S., C.J.T. and E.W. The project administration was undertaken by K.P., with A.H., M.H., K.B. and C.H. supervising. F.B., M.W., A.J., R.L., R.O. and K.T. provided expertise from lived experience in the two contexts. K.P., A.H., M.H., K.B. and C.H. drafted the original manuscript, and all authors contributed to reviewing and editing it. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author (K.P.) was funded by the HARP PhD Programme to conduct this research. The qualitative study was funded by Barts Charity. A.H. is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration North Thames. M.H. is supported by the NIHR Global Health Research Professorial Fellowship (NIHR302422) and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service (NHS), the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the NHS Health Research Authority (ref 20/YH/0311, approval date 4 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the scientific advisory board (Michelle Heys, Monica Lakhanpaul, Christopher Morris, Cally J. Tann, Phillip Harniess, Hannah Kuper, Emma Wilson, Io Vassiliadou, Sayeeda Ali and Sasha Lewis-Jackson) for their role in the original grant application, data collection, analysis and project administration of the qualitative study which guided much of the subsequent adaptation outlined in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Operationalisation of the ADAPT Phases

| ADAPT Phase | Operationalisation for the Encompass Study |

| Formation of the adaptation team | The adaptation team was formed at the beginning of the project including the core research group, caregivers with lived experience, health professionals and academic researchers who were involved in the original development of the “Baby Ubuntu” programme and subsequent implementation and adaptations in LMICs, and professionals with expertise in relation to the clinical population, the development and evaluation of complex interventions, and the NHS/UK context. The adaptation team met every 6 months to explore key uncertainties, share local perspectives, develop the programme theory, and make decisions about the programme manual and delivery plan. |

| Assessing the rationale for intervention and considering intervention-context fit | We conducted a qualitative interview study to explore local perspectives about the rationale for the intervention, the intervention’s fit for the context, and local recommendations for the new programme manual and delivery plan. In this qualitative study, healthcare professionals and caregivers working with children with complex neurodisability were interviewed about their needs and priorities, which provided much of the rationale for the intervention. Participants from the qualitative study were also shown a presentation about the “Ubuntu” programme and asked general questions about the content, format, and ways to reach diverse groups. Subsequently, questions were asked about each module. The similarities and differences between the two contexts were explored in site visits by the lead researcher and in discussions with caregivers and healthcare professionals in each context. Intellectual property rights were considered throughout the process. |

| Planning for and undertaking adaptations | The manual and delivery plan were co-created through several iterative cycles. Based on feedback from the qualitative interviews and meetings with the adaptation team, the ten modules were decided upon. The parents with lived experience contributed heavily to the manual adaptation to ensure that pictures and examples were relevant to the local context. Having the initial developers of the programme on the adaptation team allowed for the core values of the programme to remain the same. The costs and resources required to test the intervention were managed by the lead researcher. Further information on the plan for evaluation, may be found in the pilot and feasibility study protocol [41]. |

| Implementing and maintaining the intervention at scale | This will be the next step after evaluating the intervention for feasibility and acceptability. A larger implementation study will be conducted with the view of exploring sustainability and cost-effectiveness. |

Appendix A.2. Examples of Specific Feedback and Adaptation Decisions

It is not possible to capture every decision made during the adaptation process; however, an ongoing list of decisions was kept throughout the process. This allowed a trail to be created linking decisions to specific meetings and discussions. Readers may find the structure of this useful for future adaptations, and the examples help to enhance the transparency of the adaptation process.

| Date | Meeting Attendee(s) | Themes/Questions | Decisions |

| January 2023 | KP and TS | Recruiting facilitators, manual, and home visits | No funding in the original grant for parent facilitators, agreed that this was a core value of the programme and funding needed to be sought for this. To apply fast-tracking learning to the manual during workshops, training and piloting. Home visits not needed for this group (already receiving therapy support for this). |

| February 2023 | Adaptation team | Population | Decided not to be too narrow with the population (i.e., not just cerebral palsy) but open up to wider complex neurodisability |

| May 2023 | Adaptation team | Online/in-person delivery How many family members to attend? Outcome measures Specific module discussions | Best for delivery to all to be in person so that group dynamics are not affected. Could consider a hybrid when the group is more established. To keep it to 1–2 family members per child. To consider measuring empowerment as opposed to children’s quality of life, which is often too distal to what the programme can achieve. Changing the name of ‘Everyday Activities’ to ‘Everyday Routines’ ‘Our Community’ module discussion of the importance of addressing stigma in the local communities ‘Going to School’ agreed on the importance of this new module |

| June 2023 | Parent partners and KP | Facilitators Module adaptations | Came up with a job description for the parent facilitator To have facilitators who understand the local contexts (should either work or live in the two boroughs where the study is taking place) Started working through modules 0–2 |

| October 2023 | KP and C.T. | Recruiting facilitators | Parent partners felt strongly that the parent facilitator should have lived experience of having a child with a complex neurodisability. We had many parents apply who had children with social communication difficulties or autism. Parent partners felt that they needed better representation and a space of their own as they often feel like they are in the back seat compared to parents of autistic children. |

| November 2023 | Adaptation team | Recruiting facilitators Venues Frequency of groups | Discussed the overrepresentation of parents of autistic children volunteering themselves to be facilitators and how others have found the same in the UK. Looking for community venues, discussed how it needs to be a neutral space that is accessible, clean and open. Decided on fortnightly groups across two school terms |

| March 2024 | Parent partners and KP | Module content | Adaptations made to modules 3–5 |

| April 2024 | KP and facilitators during training | Running of the groups Module content | It was decided that parents would benefit from text reminders (if they consented to this) the day before the groups to remind them Adaptations made to modules throughout the training |

| June 2024 | Parent partners and KP | Module content | Adaptations made for modules 6–10 |

References

- Rosenbaum, P. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2007, 49, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Colver, A.; Fairhurst, C.; Pharoah, P.O.D. Cerebral palsy. Lancet 2014, 383, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children and Youth Version: ICF-CY 2007; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43737 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Patel, D.R.; Neelakantan, M.; Pandher, K.; Merrick, J. Cerebral palsy in children: A clinical overview. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9 (Suppl. S1), S125–S135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygård, C.; Clancy, A. Unsung heroes, flying blind-A metasynthesis of parents’ experiences of caring for children with special health-care needs at home. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3179–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Cerebral Palsy in Under 25s: Assessment and Management (NG62); National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng62/resources/cerebral-palsy-in-under-25s-assessment-and-management-pdf-1837570402501 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Each and Every Need. [Internet]. London. 2018. Available online: https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2018report1/downloads/EachAndEveryNeed_ShortReport.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Carter, B.; Bennett, C.V.; Jones, H.; Bethel, J.; Perra, O.; Wang, T.; Kemp, A. Healthcare use by children and young adults with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2021, 63, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.L.; Shlobin, N.A.; Winterhalter, E.; Lam, S.K.; Raskin, J.S. Gaps in transitional care to adulthood for patients with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2023, 39, 3083–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, D.; Bull, R.; Winzenberg, T. The daily patterns of time use for parents of children with complex needs: A systematic review. J. Child. Health Care 2012, 16, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokcin Eminel, A.; Kahraman, T.; Genc, A. Physical workload during caregiving activities and related factors among the caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 190, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, L.N.; Pechlivanoglou, P.; Lee, Y.; Mahant, S.; Orkin, J.; Marson, A.; Cohen, E. Health Outcomes of Parents of Children with Chronic Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2020, 218, 166–177.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, H.; Erkin, G.; Nalbant, L. Depression and anxiety levels in mothers of children with cerebral palsy: A controlled study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayles, E.; Harvey, D.; Plummer, D.; Jones, A. Parents’ Experiences of Health Care for Their Children With Cerebral Palsy. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.; Shelly, A.; Waters, E.; Boyd, R.; Cook, K.; Davern, M. The impact of caring for a child with cerebral palsy: Quality of life for mothers and fathers. Child Care Health Dev. 2010, 36, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pevalin, D.J. Socio-economic inequalities in health and service utilization in the London Borough of Newham. Public. Health 2007, 121, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Tower Hamlets Annual Public Health Report 2022 [Internet]. p. 2022. Available online: https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Public-Health/TowerHamletsPublicHealthReport2022.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Trust for London. Poverty and Inequality Data [Internet] 2024. Available online: https://trustforlondon.org.uk/data/boroughs/ (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- GeoData Institute. Health Literacy GeoData UK [Internet] 2019. Available online: http://healthliteracy.geodata.uk/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Aston-Mansfield. Newham: Key Statistics. A Detailed Profile of Key Statistics About Newham by Aston-Mansfield’s Community Involvement Unit [Internet] 2017. Available online: https://www.aston-mansfield.org.uk/wp-content/themes/aston_mansfield/uploads/Newham_Statistics_2017.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Kuhlthau, K.A.; Bloom, S.; Van Cleave, J.; Knapp, A.A.; Romm, D.; Klatka, K.; Homer, C.J.; Newacheck, P.W.; Perrin, J.M. Evidence for Family-Centered Care for Children With Special Health Care Needs: A Systematic Review. Acad. Pediatr. 2011, 11, 136–143.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConkey, R.; O’Hagan, P.; Corcoran, J. Parental Perceptions of Family-Centred Supports for Children with Developmental Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, D.Z.; Houtrow, A.J.; Arango, P.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Simmons, J.M.; Neff, J.M. Family-Centered Care: Current Applications and Future Directions in Pediatric Health Care. Matern. Child. Health J. 2012, 16, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prest, K.; Wilson, E.; Vassiliadou, I.; Ali, S.; Lakhanpaul, M.; Morris, C.; Tann, C.; Harniess, P.; Lewis-Jackson, S.; Kuper, H.; et al. ‘There was nothing, just absolute darkness’: Understanding the needs of those caring for children and young people with complex neurodisability in a diverse UK context: A qualitative exploration in the ENCOMPASS study. Child Care Health Dev. 2024, 50, e13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heys, M.; Lakhanpaul, M.; Allaham, S.; Manikam, L.; Owugha, J.; Oulton, K.; Morris, C.; Martin, K.R.; Tann, C.; Martin, J.; et al. Community-based family and carer-support programmes for children with disabilities. Paediatr. Child. Health 2020, 30, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S.; Holton, E.F.; Swanson, R.A. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2005; 378p. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyunja, C.; Sadoo, S.; Kohli-Lynch, M.; Nalugya, R.; Nyonyintono, J.; Muhumuza, A.; Katumba, K.R.; Trautner, E.; Magnusson, B.; Kabugo, D.; et al. Early care and support for young children with developmental disabilities and their caregivers in Uganda: The Baby Ubuntu feasibility trial. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 981976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuurmond, M.; O’Banion, D.; Gladstone, M.; Carsamar, S.; Kerac, M.; Baltussen, M.; Tann, C.J.; Nyante, G.G.; Polack, S.; Martinuzzi, A. Evaluating the impact of a community-based parent training programme for children with cerebral palsy in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smythe, T.; Reichenberger, V.; Pinzón, E.M.; Hurtado, I.C.; Rubiano, L.; Kuper, H. The feasibility of establishing parent support groups for children with congenital Zika syndrome and their families: A mixed-methods study. Wellcome Open Res. 2023, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duttine, A.; Smythe, T.; Calheiros de Sa, M.R.; Ferrite, S.; Moreira, M.E.; Kuper, H. Juntos: A Support Program for Families Impacted by Congenital Zika Syndrome in Brazil. Glob. Health Sci. Pr. 2020, 8, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalugya, R.; Nambejja, H.; Nimusiima, C.; Kawesa, E.S.; van Hove, G.; Seeley, J.; Mbazzi, F.B. Obuntu bulamu: Parental peer-to-peer support for inclusion of children with disabilities in Central Uganda. Afr. J. Disabil. 2023, 12, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tann, C.J.; Kohli-Lynch, M.; Nalugya, R.; Sadoo, S.; Martin, K.; Lassman, R.; Nanyunja, C.; Musoke, M.; Sewagaba, M.; Nampijja, M.; et al. Surviving and Thriving. Infants Young Child. 2021, 34, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tann, C.; Baganizi, E. Evaluating a Programme of Early Assessment, Care and Support for Children at Risk of Developmental Disabilities and Their Caregivers in Rwanda: The PDC/Baby Ubuntu Trial [Internet]. ISRCTN; 2024 Jul Report No.: ISRCTN17523514. Available online: https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN17523514 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Bhatti, Y.A.; Prime, M.; Harris, M.; Wadge, H.; McQueen, J.; Patel, H.; Carter, A.W.; Parston, G.; Darzi, A. The search for the holy grail: Frugal innovation in healthcare from low-income or middle-income countries for reverse innovation to developed countries. BMJ Innov. 2017, 3, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerich, G.V.; Cancellier, É.L.P.D.L. Frugal Innovation: Origins, evolution and future perspectives. Cad. Ebapebr. 2019, 17, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M. Decolonizing Healthcare Innovation Low-Cost Solutions from Low-Income Countries, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Marti, J.; Watt, H.; Bhatti, Y.; Macinko, J.; Darzi, A.W. Explicit Bias Toward High-Income-Country Research: A Randomized, Blinded, Crossover Experiment of English Clinicians. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.; Weisberger, E.; Silver, D.; Dadwal, V.; Macinko, J. That’s not how the learning works—The paradox of Reverse Innovation: A qualitative study. Glob. Health 2016, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The King’s Fund. The NHS in a Nutshell [Internet] 2024. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Harris, M.; Bhatti, Y.; Buckley, J.; Sharma, D. Fast and frugal innovations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 814–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prest, K.; Harden, A.; Barnicot, K.; Heys, M. A coadapted community-based participatory group programme for parents/carers of children with complex neurodisability (Encompass-2): A pilot and feasibility study protocol. Pilot. Feasibility Stud. 2025, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.; Campbell, M.; Copeland, L.; Craig, P.; Movsisyan, A.; Hoddinott, P.; Littlecott, H.; O’Cathain, A.; Pfadenhauer, L.; Rehfuess, E.; et al. Adapting interventions to new contexts—The ADAPT guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, D.W.; van Meeteren, K.; Klem, M.; Alsem, M.; Ketelaar, M. Designing a tool to support patient and public involvement in research projects: The Involvement Matrix. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2020, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, A.W.; Kragh-Sørensen, A.; Børgesen, K.; Behrens, K.E.; Andersen, T.; Kidholm, M.L.; Rothmann, M.J.; Ketelaar, M.; Janssens, A. Roles, outcomes, and enablers within research partnerships: A rapid review of the literature on patient and public involvement and engagement in health research. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2023, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Cardon, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verloigne, M.; Chastin, S.F.M.; on behalf of the GrandStand, Safe Step and Teenage Girls on the Move Research Groups. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2019, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albayrak, I.; Biber, A.; Çalışkan, A.; Levendoglu, F. Assessment of pain, care burden, depression level, sleep quality, fatigue and quality of life in the mothers of children with cerebral palsy. J. Child. Health Care 2019, 23, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbatha, N.L.; Mokwena, K.E. Parental Stress in Raising a Child with Developmental Disabilities in a Rural Community in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. Featured Article: Depressive Symptoms in Parents of Children With Chronic Health Conditions: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambi, J.M.; Jelsma, J.; Mlambo, T. Caring for a child with Cerebral Palsy: The experience of Zimbabwean mothers. Afr. J. Disabil. 2015, 4, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyong, K.I.; Ekanem, E.E.; Asindi, A.A. Challenges of care givers of children with cerebral palsy in a developing country. Int. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2017, 4, 1128–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagosh, J. Realist Synthesis for Public Health: Building an Ontologically Deep Understanding of How Programs Work, For Whom, and In Which Contexts. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 2019, 40, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawson, R. The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013; 244p. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, J.; Manzano, A. Understanding ‘context’ in realist evaluation and synthesis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2022, 25, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borek, A.J.; Abraham, C.; Greaves, C.J.; Gillison, F.; Tarrant, M.; Morgan-Trimmer, S.; McCabe, R.; Smith, J.R. Identifying change processes in group-based health behaviour-change interventions: Development of the mechanisms of action in group-based interventions (MAGI) framework. Health Psychol. Rev. 2019, 13, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borek, A.J.; Abraham, C.; Smith, J.R.; Greaves, C.J.; Tarrant, M. A checklist to improve reporting of group-based behaviour-change interventions. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, P.; Stanschus, S.; Zaman, R.; Cichero, J.A.Y. The International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) framework: The Kempen pilot. Br. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2017, 13, S18–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, A.J.; McDonald, B.; Fredlund, M.; Bjornstad, G.; Logan, S.; Morris, C. Healthy Parent Carers programme: Development and feasibility of a novel group-based health-promotion intervention. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, A.; Islam, S.; Haklay, M.; McEachan, R.R.C. Nothing about us without us: A co-production strategy for communities, researchers and stakeholders to identify ways of improving health and reducing inequalities. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggleby, W.; Peacock, S.; Ploeg, J.; Swindle, J.; Kaewwilai, L.; Lee, H. Qualitative Research and Its Importance in Adapting Interventions. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, J.; Paparini, S.; Papoutsi, C.; James, H.; Greenhalgh, T.; Shaw, S.E. Mobilising context as complex and dynamic in evaluations of complex health interventions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, D.; Kapilashrami, A.; Kumar, R.; Rhule, E.; Khosla, R. Developing an agenda for the decolonization of global health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2023, 102, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuck, E.; Yang, K.W. Decolonization Is not a Metaphor. Decolon. Indig. Educ. Soc. 2012, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Smythe, T.; Le, G.; Owen, R.; Ayana, B.; Hansen, L.; Lavy, C. The development of a training course for clubfoot treatment in Africa: Learning points for course development. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smythe, T.; Owen, R.; Le, G.; Uwizeye, E.; Hansen, L.; Lavy, C. The feasibility of a training course for clubfoot treatment in Africa: A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavy, C. Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences [Internet]. Africa Clubfoot Training (ACT). Available online: https://www.ndorms.ox.ac.uk/research/research-groups/global-surgery/projects/africa-clubfoot-training-act (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Bonell, C.; Prost, A.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Davey, C.; Hargreaves, J.R. Will it work here? A realist approach to local decisions about implementing interventions evaluated as effective elsewhere. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).