Navigating Workforce Challenges in Long-Term Care: A Co-Design Approach to Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Co-Design and Its Methodological Benefits

- Observation: A researcher or non-participant examines the clinical environment to understand user-provider interactions.

- Provider interviews: Interviews with healthcare providers contextualize service delivery and identify key pressure points.

- User interviews: Service users share their experiences, highlighting critical moments in their care journey.

- Data analysis: Emerging shared narratives of defining moments, or touchpoints, capture the essence of both care experiences and workplace dynamics (or work environment).

2.3. Sampling, Participants, and Sample Size

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics Approval and Considerations

3. Results

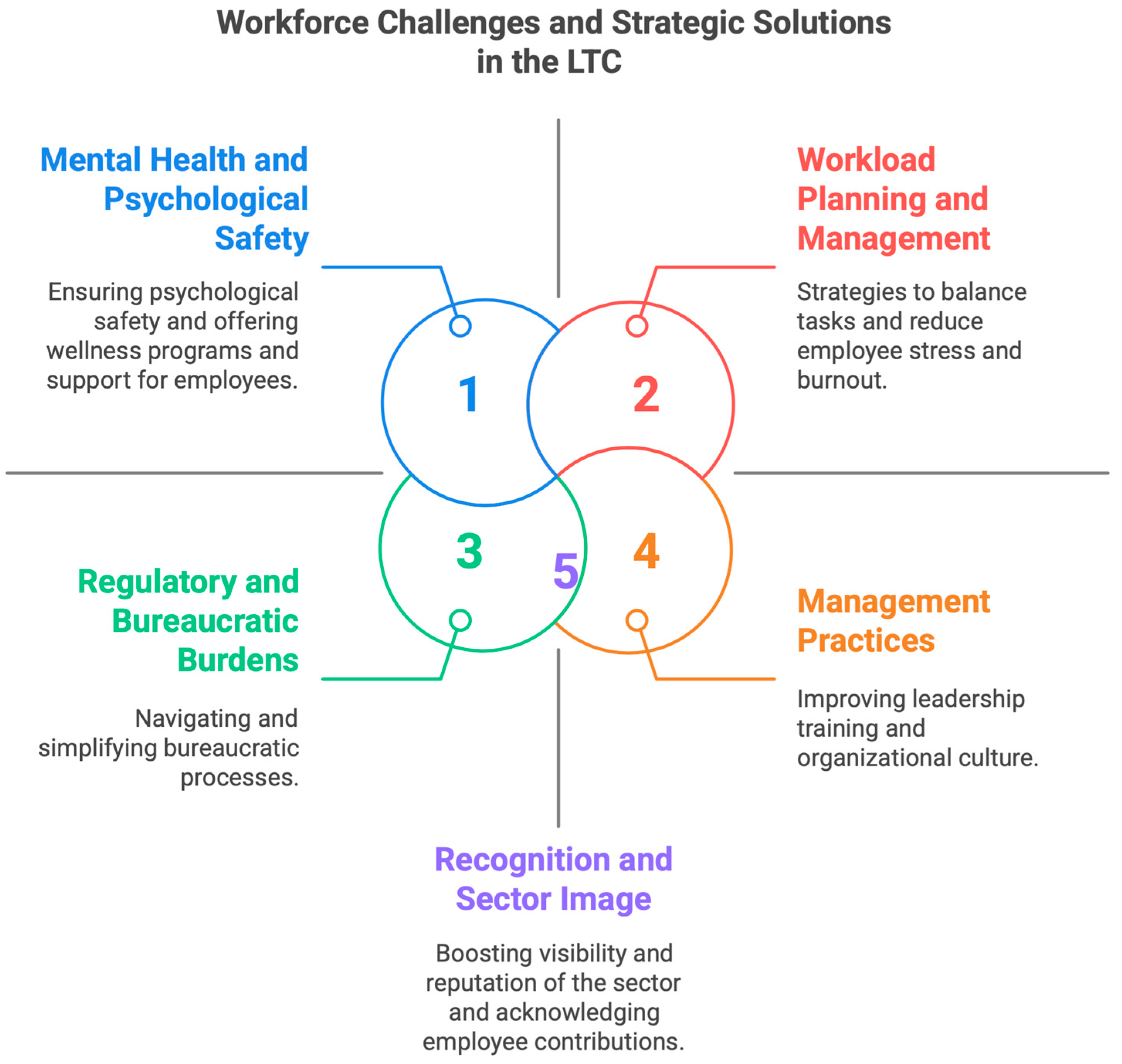

3.1. Identified Needs and Challenges

3.1.1. The Need for Effective Workload Management Tools

“To make up for missed coworkers, many employees put in extra hours, even going above and beyond their full-time schedules. I personally had worked part-time during the pandemic but was working over full-time hours because there just were not enough nurses… The nurses we have were burning out.”(Assistant Director of Nursing01)

“Now I find in the PSW staff that they are taking stress leaves, and they are taking, you know, time off and or quitting the field entirely.”(Assistant Director of Nursing02)

3.1.2. The Prioritization of Psychological Safety and Mental Health Services

“It is very much like you’re drowning and I know the frontline felt like that, too.”(SW01)

“The staff, I feel, are burnt out and looking to management for some support, but management themselves are burnt out.”(Assistant Director of Nursing01)

“I will tell you; we have had more people than I have ever known before, disclose that they started an anti-anxiety or an anti-depression medication during the course of COVID.”(Horticulture Therapist)

“There’s a lot of, there’s a lot of PTSD among a lot of different team members that I’ve seen and experienced, and even personal experience, where, you know, you feel for everything you’ve gone through, and, you know, and if you’re not in long term care, you don’t fully know.”(Administrator 01)

“You start to get isolated from your friends and your family. It’s very sad, actually,”(SW02)

“You’re not allowed to be selfish if you’re a caregiver, but it’s not really selfish. It’s about taking care of yourself.”(SW02)

3.1.3. Reducing Regulatory and Bureaucratic Burdens

“We have both Ministry of Health and Public Health at the same time… it was so insulting and so degrading to have outside people coming in to teach us what to do like we had never been in the sector before.”(SW02)

3.1.4. Strengthening Management Practices

“My employer ended up finding a way to push me out of a job I had for 16 years… the new management treats people horribly.”(Manager02)

“I think that we just become numbers… making sure we are compliant with the ministry and all of that… there is some aspect of micromanaging for certain areas of our work, which makes it difficult.”(SW02)

3.1.5. Fostering Recognition and a Positive Sector Image

“We were never acknowledged for our knowledge for our work. And it was very, very upsetting.”(SW02)

“There has never, to my knowledge, been any acknowledgement of anything that happened during COVID… none.”(SW01)

“You do not have any more time left, and then you are still not appreciated.”(Manager02)

“It’s frustrating that no one talks about how we heal, how we bring people back to life but they just focus on the failures.”(Manager01)

“The senior leadership needs to acknowledge us more—our efforts, our sacrifices, our humanity. That would make a huge difference. We need more than pizza parties. We need respect, acknowledgment, and appreciation for what we do.”(Manager01)

3.2. Proposed Strategies

3.2.1. Workforce Planning

“I think having permanent staff would be a much better solution. Somehow, finding a way to retain staff and new graduates, making long-term care a more attractive option, would help. Right now, a lot of young nurses don’t even want to work here because hospitals pay more.”(RPN01)

3.2.2. Mental Health Programs

“Health and safety might help with the psychological health and safety as a mandated component.”(SW01)

3.2.3. Self-Care Promotion

“We are really of no use to anybody when we’re not rested, and when we’re not in a good space ourselves.”(Behavioral Therapist)

3.2.4. Enforcing Work–Life Boundaries

“People like me are not allowed to not be called on vacation or at one in the morning… you have to have a safe space in your personal life to be able to come back.”(SW01)

3.2.5. Fostering Psychological Safety in LTC Settings

“Management needs to understand the mental toll that abuse from residents takes on us. There should be regular check-ins, counseling options, or just an acknowledgment that we need support.”(PSW01)

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Long-Term Care and COVID-19: The First 6 Months; Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/impact-covid-19-long-term-care-canada-first-6-months-report-en.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Long-Term Care Homes in Canada: How Many and Who Owns Them? 2021. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/long-term-care-homes-in-canada-how-many-and-who-owns-them#:~:text=The%20proportion%20of%20private%20and,of%20homes%20by%20ownership%20type (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Boscart, V.M.; Sidani, S.; Poss, J.; Davey, M.; d’Avernas, J.; Brown, P.; Heckman, G.; Ploeg, J.; Costa, A.P. The associations between staffing hours and quality of care indicators in long-term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018, 18, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A. Chapter 6: The Regulatory Trap: Reflections on the Vicious Cycle of Regulation in Canadian Residential Care. In Stockholm Studies in Social Work; Meagher, G., Marta Szebehely, M., Eds.; Department of Social Work, Stockholm University: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013; pp. 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich, G.S.; Kohler, P.O. Improving the Quality of Long-Term Care; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; p. 9611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabrooks, C.A.; Straus, S.E.; Flood, C.M.; Keefe, J.; Armstrong, P.; Donner, G.J.; Boscart, V.; Ducharme, F.; Silvius, J.L.; Wolfson, M.C. Restoring Trust: COVID-19 and the Future of Long-Term Care in Canada. FACETS 2020, 5, 651–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada 2022–2023 Departmental Results Report Supplementary Information Table; Public Health Agency Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2024/aspc-phac/HP2-27-1-2023-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Clarke, J. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Nursing and Residential Care Facilities in Canada; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00025-eng.pdf?st=aKiDBoBK (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Garnett, A.; Hui, L.; Oleynikov, C.; Boamah, S. Compassion fatigue in health providers: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boamah, S.A.; Weldrick, R.; Havaei, F.; Irshad, A.; Hutchinson, A. Experiences of Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care during COVID-19: A Scoping Review. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 1118–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahim, C.; Hassan, A.T.; Quinn De Launay, K.; Takaoka, A.; Togo, E.; Strifler, L.; Bach, V.; Paul, N.; Mrazovac, A.; Firman, J.; et al. Challenges Facing Canadian Long-Term Care Homes and Retirement Homes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Syst. Qual. Improv. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shembavnekar, N.; Buchan, P.J.; Bazeer, N.; Kelly, E.; Beech, J.; Charlesworth, A.; McConkey, R.; Fisher, R. NHS Workforce Projections 2022|The Health Foundation; The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/reports/nhs-workforce-projections-2022 (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Ministry of Long Term Care. Long-Term Care Staffing Study; Government of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020.

- Giebel, C.; Hanna, K.; Marlow, P.; Cannon, J.; Tetlow, H.; Shenton, J.; Faulkner, T.; Rajagopal, M.; Mason, S.; Gabbay, M. Guilt, Tears and Burnout—Impact of UK Care Home Restrictions on the Mental Well-Being of Staff, Families and Residents. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2191–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, A.E.; Hafstad, E.V.; Himmels, J.P.W.; Smedslund, G.; Flottorp, S.; Stensland, S.Ø.; Stroobants, S.; Van De Velde, S.; Vist, G.E. The Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers, and Interventions to Help Them: A Rapid Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyamoorthy, T. Supporting Support Workers: PSWs Need Increased Protections During COVID-19. Available online: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/work-health/supporting-support-workers-psws-need-increased-protections-during-covid-19/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Probes, Toolkits and Prototypes: Three Approaches to Making in Codesigning. CoDesign 2014, 10, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G.; Locock, L.; Williams, O.; Cornwell, J.; Donetto, S.; Goodrich, J. Co-Producing and Co-Designing, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, V.N.; Cho, S.M.; Huang, C.-M. Co-Designing with Older Adults, for Older Adults: Robots to Promote Physical Activity. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–16 March 2023; ACM: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023; pp. 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvale, G.; Moll, S.; Miatello, A.; Robert, G.; Larkin, M.; Palmer, V.J.; Powell, A.; Gable, C.; Girling, M. Codesigning Health and Other Public Services with Vulnerable and Disadvantaged Populations: Insights from an International Collaboration. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, B.; Haveman, A.; Abma, T. Relational, Ethically Sound Co-Production in Mental Health Care Research: Epistemic Injustice and the Need for an Ethics of Care. Crit. Public Health 2022, 32, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, P.; Robert, G. Experience-Based Design: From Redesigning the System around the Patient to Co-Designing Services with the Patient. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Gillmore, C.; Hogg, L. Experience-Based Co-Design in an Adult Psychological Therapies Service. J. Ment. Health 2016, 25, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silcock, J.; Marques, I.; Olaniyan, J.; Raynor, D.K.; Baxter, H.; Gray, N.; Zaidi, S.T.R.; Peat, G.; Fylan, B.; Breen, L.; et al. Co-designing an Intervention to Improve the Process of Deprescribing for Older People Living with Frailty in the United Kingdom. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, P.; Robert, G. Bringing User Experience to Healthcare Improvement: The Concepts, Methods and Practices of Experience-Based Design; Radcliffe Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Standards Association; Bureau de normalisation du Québec. Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace—Prevention, Promotion, and Guidance to Staged Implementation. 2013. Available online: https://www.csagroup.org/store-resources/documents/codes-and-standards/2421865.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Moser, T. The Art of Coding and Thematic Exploration in Qualitative Research. IMR 2019, 15, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowinski, B.; Vellani, S.; Aboumrad, M.; Beogo, I.; Frank, T.; Havaei, F.; Kaasalainen, S.; Lashewicz, B.; Levy, A.-M.; McGilton, K.; et al. The Canadian Long-Term Care Sector Collapse from COVID-19: Innovations to Support People in the Workforce. Healthc. Q. 2022, 25, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Hopwood, P.; Haghighi, P.; Littler, E.; Davis, A.; Al Momani, Y.; MacEachen, E. Does Staffing Impact Health and Work Conditions of Staff in Long-Term Care Homes?: A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34 (Suppl. S3), ckae144.869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugler, J.E. The Challenge of Workforce Retention in Long-Term Care. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2014, 33, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L. The Effectiveness of Distraction as Preoperative Anxiety Management Technique in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 133, 104288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle, E.S.; Walecka, A.; Sangam, A.V.; Moorhouse, J.; Winter, M.; Munro Wild, H.; Trivedi, D.; Casarin, A. Triggers and Factors Associated with Moral Distress and Moral Injury in Health and Social Care Workers: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, A.; Milliken, A.; Leiter, R.E.; Blum, D.; Slavich, G.M. The Psychoneuroimmunological Model of Moral Distress and Health in Healthcare Workers: Toward Individual and System-Level Solutions. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2024, 17, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, M.; Devey-Burry, R.; Hu, J.; Angus, D.E.; Backman, C. The Role of Regulation in the Care of Older People with Depression Living in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Scoping Review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, A.M.; Kok, J.; Schoonmade, L.J.; Bal, R.A. Regulation of Long-Term Care for Older Persons: A Scoping Review of Empirical Research. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaei, F.; Ma, A.; Staempfli, S.; MacPhee, M. Nurses’ Workplace Conditions Impacting Their Mental Health during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario. Ontario’s Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission-Final Report; Government of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/long-term-care-covid-19-commission-progress-interim-recommendations (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Elstad, J.I.; Vabø, M. Lack of Recognition at the Societal Level Heightens Turnover Considerations among Nordic Eldercare Workers: A Quantitative Analysis of Survey Data. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcella, J.; Nadarajah, J.; Kelley, M.L.; Heckman, G.A.; Kaasalainen, S.; Strachan, P.H.; McKelvie, R.S.; Newhouse, I.; Stolee, P.; McAiney, C.A.; et al. Understanding Organizational Context and Heart Failure Management in Long Term Care Homes in Ontario, Canada. Health 2012, 04, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, A.; Deber, R.; Laporte, A. Forecasting Staffing Needs for Ontario’s Long-Term Care Sector. Healthc. Policy 2022, 17, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applebaum, R.; Janssen, L.; Applebaum, R. Who cares? Retention Strategies for Direct Care Workers. Innov. Aging 2023, 7 (Suppl. S1), 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salalila, L. An Evidence-Based Approach for Decreasing Burnout in Health Care Workers; University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, M.; Westrick, A.; Bawa, R.; Gabram, O.; Blake, A.; Emerson, B. Sustained Resiliency Building and Burnout Reduction for Healthcare Professionals via Organizational Sponsored Mindfulness Programming. Explore 2022, 18, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.E.; Hollensbe, E.C.; Sheep, M.L. Boundary Work Tactics: Negotiating The Work-Home Interface. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2006, 2006, K1–K6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.; Carini, C. A Moment of Peace: Utilizing Practical on the Job Relaxation and Meditation Techniques to Improve Feelings of Stress and Burnout among Healthcare Professionals. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2023, 31, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyer, A.; Taylor, R.; Kennedy, K. Fostering Compassion and Reducing Burnout: How Can Health System Leaders Respond in the Covid-19 Pandemic and Beyond? Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 94, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghossoub, Z.; Nadler, R.; El-Aswad, N. Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, Self-Care, and Self-Leadership in Healthcare Workers Burnout: A Qualitative Study in Coaching. Undergrad. J. Public Health 2020, 8, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.-Y.; Tang, H.-C.; Lu, S.-C.; Lee, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-C. Transformational Leadership and Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019899085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, N.; Young, V.N.; Shapiro, J.; Brenner, M.J.; Schmalbach, C.E. Patient Safety/Quality Improvement Primer, Part IV: Psychological Safety—Drivers to Outcomes and Well-being. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 168, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, S.; Haeger, M.; Kühnlein, L.; Sulmann, D.; Suhr, R. Interventions to Enhance Safety Culture for Nursing Professionals in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2023, 5, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada; Health Canada. Nursing Retention Toolkit: Improving the Working Lives of Nurses in Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/health-care-system/health-human-resources/nursing-retention-toolkit-improving-working-lives-nurses/nursing-retention-toolkit-improving-working-lives-nurses.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

| Profile | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 21 (87.5) |

| Male | 3 (12.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 16 (66.7) |

| Other | 8 (33.3) |

| Role/job title | |

| Personal support worker (PSW) | 10 (41.7) |

| Nurse (RN/RPN) | 5 (20.8) |

| Leader (director/manager/administrator) | 5 (20.8) |

| Allied health (social worker, behavioral and horticultural therapist) | 4 (16.7) |

| Age range | 27–71 years |

| Mean | 50 years |

| Years of experience | 1–30 years |

| Identified Challenges | Proposed Strategies and Solutions |

|---|---|

Workload Management

| Workload Planning and Management

|

Mental Health and Psychological Safety

| Mental Health Program and Promoting Psychological Safety

|

Regulatory and Bureaucratic Burdens

| Streamlined Communication and Policy Coordination

|

Management Practices

| Fostering a Supportive and Empathetic Management Culture

|

Recognition and Sector Image

| Encouraging Recognition and Elevating the LTC Sector’s Image

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boamah, S.A.; Akter, F.; Karimi, B.; Havaei, F. Navigating Workforce Challenges in Long-Term Care: A Co-Design Approach to Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040520

Boamah SA, Akter F, Karimi B, Havaei F. Navigating Workforce Challenges in Long-Term Care: A Co-Design Approach to Solutions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040520

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoamah, Sheila A., Farzana Akter, Bahar Karimi, and Farinaz Havaei. 2025. "Navigating Workforce Challenges in Long-Term Care: A Co-Design Approach to Solutions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040520

APA StyleBoamah, S. A., Akter, F., Karimi, B., & Havaei, F. (2025). Navigating Workforce Challenges in Long-Term Care: A Co-Design Approach to Solutions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040520