Physical Activity as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Body Image Perception and Low Mood in Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

Measurements

2.2. Statistical Analysis

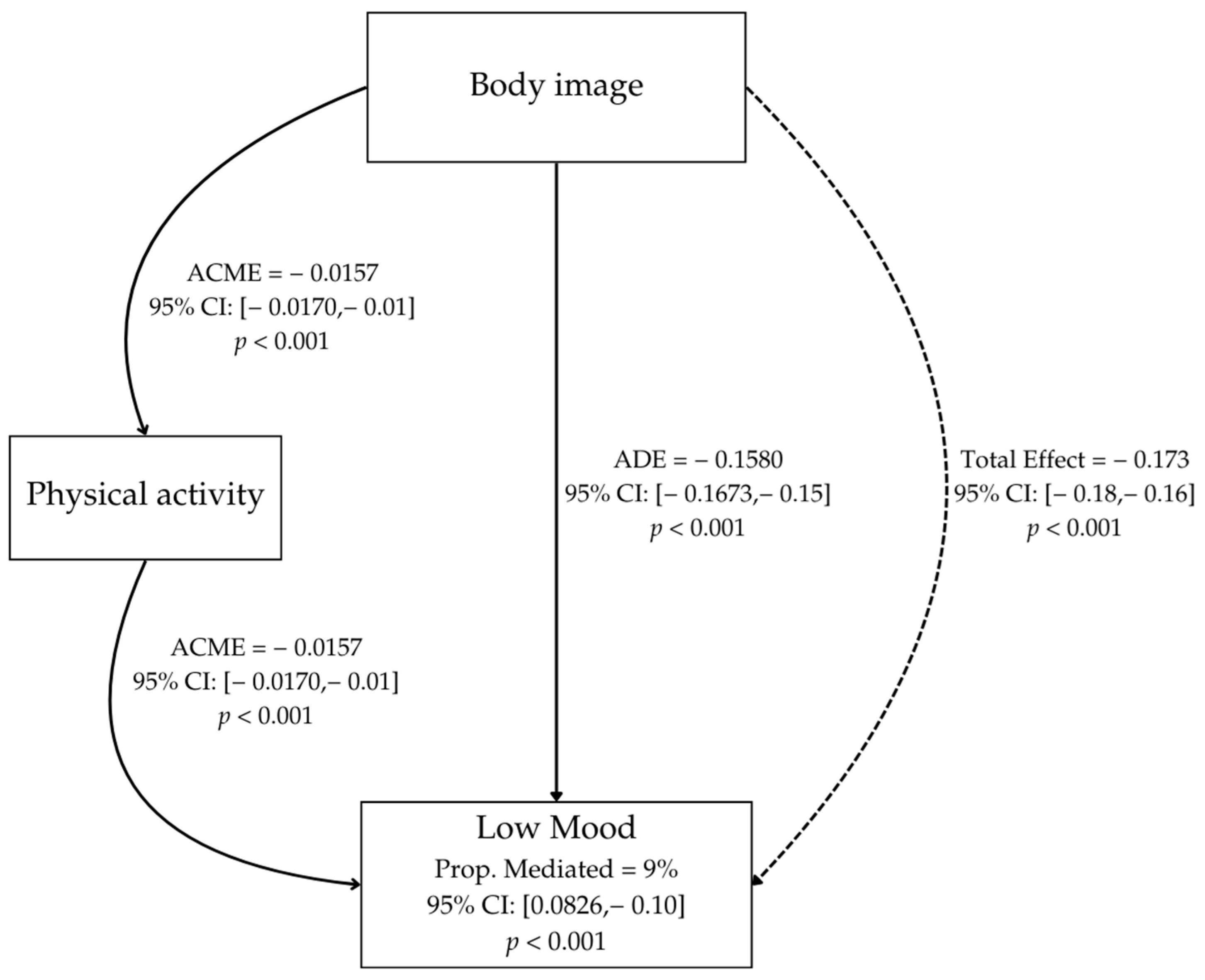

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grogan, S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-00-310004-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, P.T.; Fowler, N.; Rolan, E.P.; Culbert, K.M.; Racine, S.E.; Burt, S.A.; Klump, K.L. The Effects of Puberty on Associations between Mood/Personality Factors and Disordered Eating Symptoms in Girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1619–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchesne, A.-P.; Dion, J.; Lalande, D.; Bégin, C.; Émond, C.; Lalande, G.; McDuff, P. Body Dissatisfaction and Psychological Distress in Adolescents: Is Self-Esteem a Mediator? J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardelli, L.A.; Yager, Z. Adolescence and Body Image: From Development to Preventing Dissatisfaction; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-315-84937-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Laveway, K.; Campos, P.; Carvalho, P.H.B. de Body Image as a Global Mental Health Concern. Camb. Prisms Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.; Choi, I. The Associations between Body Dissatisfaction, Body Figure, Self-Esteem, and Depressed Mood in Adolescents in the United States and Korea: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. J. Adolesc. 2016, 53, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroor, A.R.; Galagali, P.M. Body Image during Adolescence. Indian J. Pract. Pediatr. 2021, 23, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, A.; Rosen, J.C. Obesity Stigmatization and Coping: Relation to Mental Health Symptoms, Body Image, and Self-Esteem. Int. J. Obes. 1999, 23, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares Filho, L.C.; Batista, R.F.L.; Cardoso, V.C.; Simões, V.M.F.; Santos, A.M.; Coelho, S.J.D.D.a.C.; Silva, A.a.M. Body Image Dissatisfaction and Symptoms of Depression Disorder in Adolescents. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2020, 54, e10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, E.; De Stavola, B.L.; Kellock, M.D.; Kelly, Y.; Lewis, G.; McMunn, A.; Nicholls, D.; Patalay, P.; Solmi, F. Longitudinal Pathways between Childhood BMI, Body Dissatisfaction, and Adolescent Depression: An Observational Study Using the UK Millenium Cohort Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorup, L.; Zulfikari, M.; Sørensen, C.L.B.; Biering, K. Body Image and Depressive Symptoms in Danish Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional National Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 365, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelpietra, G.; Knudsen, A.K.S.; Agardh, E.E.; Armocida, B.; Beghi, M.; Iburg, K.M.; Logroscino, G.; Ma, R.; Starace, F.; Steel, N.; et al. The Burden of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders and Self-Harm among Young People in Europe, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 16, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi-Russo, E.; Rinaldo, N.; Zaccagni, L. Physical Activity and Body Image Perception in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, L.; Poulain, T.; Kiess, W.; Vogel, M. Body Image and Behavioural and Emotional Difficulties in German Children and Adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, M.H.; Lehtimäki, A.-V.; Roos, E.; Viljakainen, H. Body Mass Index, Physical Activity, and Body Image in Adolescents. Child. Basel Switz. 2022, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ayed, H.; Yaich, S.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Ben Hmida, M.; Trigui, M.; Jedidi, J.; Sboui, I.; Karray, R.; Feki, H.; Mejdoub, Y.; et al. What Are the Correlates of Body Image Distortion and Dissatisfaction among School-Adolescents? Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2019, 33, 20180279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verplanken, B.; Velsvik, R. Habitual Negative Body Image Thinking as Psychological Risk Factor in Adolescents. Body Image 2008, 5, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelqvist-Schmidlechner, K.; Vaara, J.P.; Vasankari, T.; Häkkinen, A.; Mäntysaari, M.; Kyröläinen, H. Relationship between Different Domains of Physical Activity and Positive Mental Health among Young Adult Men. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; McGrane, B.; White, R.L.; Sweeney, M.R. Self-Esteem, Meaningful Experiences and the Rocky Road—Contexts of Physical Activity That Impact Mental Health in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemel, P.N.; Porter, J.E.; Coombs, N. Improving Youth Physical, Mental and Social Health through Physical Activity: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Promot. J. Aust. Off. J. Aust. Assoc. Health Promot. Prof. 2022, 33, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Baldwin, A.S.; Bryan, A.D.; Conner, M.; Rhodes, R.E.; Williams, D.M. Affective Determinants of Physical Activity: A Conceptual Framework and Narrative Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 568331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; Infantes-Paniagua, Á.; Cuevas, R.; Contreras, O.R. Effect of Physical Activity on Self-Concept: Theoretical Model on the Mediation of Body Image and Physical Self-Concept in Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Baceviciene, M. Testing Modified Gender-Moderated Exercise and Self-Esteem (EXSEM) Model of Positive Body Image in Adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1805–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonstroem, R.J.; Morgan, W.P. Exercise and Self-Esteem: Rationale and Model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1989, 21, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.M.; Evans, D.R. Current Emotion Research in Health Behavior Science. Emot. Rev. 2014, 6, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R.; Emeljanovas, A. Self-Perception of Physical Activity and Fitness Is Related to Lower Psychosomatic Health Symptoms in Adolescents with Unhealthy Lifestyles. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-Being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Survey in Europe and Canada. International Report. Volume 1. Key Findings. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289055000 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Buli, B.G.; Lehtinen-Jacks, S.; Larm, P.; Nilsson, K.W.; Hellström-Olsson, C.; Giannotta, F. Trends in Psychosomatic Symptoms among Adolescents and the Role of Lifestyle Factors. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, S.; Wold, B. Subjective Health Complaints in Adolescence—Reliability and Validity of Survey Methods. J. Adolesc. 2001, 24, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, A.; Sischka, P.E.; Catunda, C.; Cosma, A.; García-Moya, I.; Lyyra, N.; Kaman, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Pickett, W. Item Response Theory and Differential Test Functioning Analysis of the HBSC-Symptom-Checklist across 46 Countries. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2022, 22, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meland, E.; Haugland, S.; Breidablik, H.-J. Body Image and Perceived Health in Adolescence. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 22, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, T.J.; Lobstein, T. Extended International (IOTF) Body Mass Index Cut-Offs for Thinness, Overweight and Obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 7, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, I.; Winter, K.; Bilz, L.; Bucksch, J.; Finne, E.; John, N.; Kolip, P.; Paulsen, L.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Schlattmann, M.; et al. The 2017/18 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study–Methodology of the World Health Organization’s Child and Adolescent Health Study. J. Health Monit. 2020, 5, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2013/14 Survey; Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit (CAHRU): Dysart, KY, USA, 2014.

- Gariepy, G.; McKinnon, B.; Sentenac, M.; Elgar, F.J. Validity and Reliability of a Brief Symptom Checklist to Measure Psychological Health in School-Aged Children. Child Indic. Res. 2016, 9, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Willumsen, J.; Bull, F.; Chou, R.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Jago, R.; Ortega, F.B.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. 2020 WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour for Children and Adolescents Aged 5–17 Years: Summary of the Evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, T.J.; Lobstein, T. An Improved Algorithm to Harmonize Child Overweight and Obesity Prevalence Rates. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Available online: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/discovering-statistics-using-ibm-spss-statistics/book285130 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical Activity and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Review of Reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samsudin, N.; Bailey, R.P.; Ries, F.; Hashim, S.N.A.B.; Fernandez, J.A. Assessing the Impact of Physical Activity on Reducing Depressive Symptoms: A Rapid Review. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, M.; Garcia, L.; Abbas, A.; Strain, T.; Schuch, F.B.; Golubic, R.; Kelly, P.; Khan, S.; Utukuri, M.; Laird, Y.; et al. Association Between Physical Activity and Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Prochaska, J.J.; Taylor, W.C. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.J.; Kremer, P.; Douglas, K.; Toumborou, J.W.; Hameed, M.A.; Patton, G.C.; Williams, J. Gender Differences in Adolescent Depression: Differential Female Susceptibility to Stressors Affecting Family Functioning. Aust. J. Psychol. 2015, 67, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency of Physical Activity (Days) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Total (%) | ||

| Age group (%) | Aged 10–12 years | 1570 (21.2) | 2882 (26.2) | 5149 (26.7) | 7352 (28.5) | 7396 (30.6) | 7530 (32.3) | 4991 (33.1) | 10,665 (37.8) | 47,535 (30.8) |

| Aged 13–15 years | 2220 (29.9) | 3471 (31.5) | 6579 (34.2) | 8886 (34.5) | 8616 (35.6) | 8131 (34.9) | 5338 (35.4) | 9479 (33.6) | 52,720 (34.2) | |

| Aged 16–17 years | 3626 (48.9) | 4656 (42.3) | 7529 (39.1) | 9527 (35.0) | 8160 (33.8) | 7655 (32.8) | 4741 (31.5) | 8034 (28.5) | 53,928 (35.0) | |

| Sex (%) | Boy | 3093 (41.7) | 4335 (39.4) | 7598 (39.5) | 11,324 (44.0) | 11,623 (48.1) | 12,084 (51.8) | 8048 (53.4) | 16,663 (59.1) | 74,768 (48.5) |

| Girls | 4323 (58.3) | 6674 (60.6) | 11,659 (60.5) | 14,441 (54.0) | 12,549 (51.9) | 11,232 (48.2) | 7022 (46.6) | 11,515 (40.9) | 79,415 (51.5) | |

| BMI (%) | Thinness | 1122 (15.1) | 1639 (14.9) | 2275 (14.4) | 3538 (13.7) | 3281 (13.6) | 3134 (13.4) | 2056 (13.6) | 4367 (15.5) | 21,912 (14.2) |

| Normal weight | 4820 (65.0) | 7357 (66.8) | 13,016 (67.6) | 17,730 (68.8) | 17,084 (70,7) | 16,789 (72.0) | 11,181 (74.2) | 20,353 (72.2) | 108,330 (70.3) | |

| Overweight | 1159 (15.6) | 1611 (14.6) | 2754 (14.3) | 3685 (14.3) | 3114 (12.9) | 2866 (12.3) | 1574 (10.4) | 2909 (10.3) | 19,672 (12.8) | |

| Obesity | 315 (4.2) | 402 (3.7) | 712 (3.7) | 812 (3.2) | 693 (2.9) | 527 (2.3) | 259 (1.7) | 549 (1.9) | 4269 (2.8) | |

| Feeling low mood (%) | About every day | 1278 (17.2) | 1340 (12.2) | 2016 (10.5) | 2078 (8.1) | 1662 (6.9) | 1507 (6.5) | 816 (5.4) | 2074 (7.4) | 12,771 (8.3) |

| More than once/week | 1090 (14.7) | 1729 (15.7) | 2475 (12.9) | 2123 (12.2) | 2529 (10.5) | 2234 (9.6) | 1312 (8.7) | 2298 (8.2) | 16,799 (10,9) | |

| About every week | 949 (12.8) | 1565 (14.2) | 2752 (14.3) | 3549 (13.8) | 3223 (13.3) | 2799 (12.0) | 1839 (12.2) | 2805 (10.0) | 19,481 (12.6) | |

| About every month | 1205 (16.2) | 2092 (19.0) | 4084 (21.2) | 5579 (21.7) | 5401 (22.3) | 5241 (22.5) | 3337 (22.1) | 5229 (18.6) | 32,168 (20.9) | |

| Rarely or never | 2894 (39.0) | 4283 (38.9) | 7930 (41.2) | 11,427 (44.4) | 11,357 (47.0) | 11,535 (49.5) | 7766 (51.5) | 15,772 (56.0) | 72,964 (47.3) | |

| Body image (%) | Much too thin | 401 (5.4) | 453 (4.1) | 716 (3.7) | 718 (2.8) | 705 (2.9) | 665 (2.9) | 423 (2.8) | 1290 (4.6) | 5371 (3.5) |

| Bit too thin | 1125 (15.2) | 1521 (13.8) | 2725 (14.2) | 3625(14.1) | 3391 (14.0) | 3304 (14.2) | 2286 (15.0) | 4338 (15.4) | 22,315 (14.5) | |

| About right | 3454 (46.6) | 5671 (51.5) | 9903 (51.4) | 13,833 (55.7) | 13,467 (55.7) | 13,543 (58.1) | 9092 (60.3) | 17,603(62.5) | 86,569 (56.1) | |

| Bit too fat | 1903 (25.7) | 2856 (25.9) | 5126 (26.6) | 6614 (25.7) | 5882 (24.3) | 5155 (22.1) | 2920 (19.4) | 4301 (15.3) | 34,757 (22.5) | |

| Much too fat | 530 (7.1) | 508 (4.6) | 787 (4.1) | 975 (3.8) | 727 (3.0) | 649 (2.8) | 349 (2.3) | 646 (2.3) | 5171 (3.4) | |

| Low Mood Category a | Variable Predictor | Beta | OR (95% IC) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| About every day | PA 0 days | 0.78 | 2.19 (2.01–2.38) | <0.001 |

| PA 1 days | 0.52 | 1.69 (1.56–1.83) | <0.001 | |

| PA 2 days | 0.32 | 1.38 (1.29–1.48) | <0.001 | |

| PA 3 days | 0.05 | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | 0.13 | |

| PA 4 days | −0.09 | 0.91(0.84–0.97) | 0.01 | |

| PA 5 days | −0.15 | 0.86 (0.80–0.92) | <0.001 | |

| PA 6 days | −0.32 | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | <0.001 | |

| PA 7 days | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| More than once/week | PA 0 days | 0.61 | 1.84 (1.69–2.01) | <0.001 |

| PA 1 days | 0.74 | 2.10 (1.95–2.25) | <0.001 | |

| PA 2 days | 0.48 | 1.62 (1.52–1.73) | <0.001 | |

| PA 3 days | 0.40 | 1.50 (1.41–1.59) | <0.001 | |

| PA 4 days | 0.25 | 1.29 (1.21–1.37) | <0.001 | |

| PA 5 days | 0.16 | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) | <0.001 | |

| PA 6 days | 0.05 | 1.05 (0.98–1.14) | 0.12 | |

| PA 7 days | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| About every week | PA 0 days | 0.36 | 1.44 (1.32–1.57) | <0.001 |

| PA 1 days | 0.52 | 1.68 (1.56–1.80) | <0.001 | |

| PA 2 days | 0.46 | 1.59 (1.50–1.69) | <0.001 | |

| PA 3 days | 0.39 | 1.47 (1.39–1.56) | <0.001 | |

| PA 4 days | 0.34 | 1.40 (1.32–1.48) | <0.001 | |

| PA 5 days | 0.21 | 1.24 (1.17–1.31) | <0.001 | |

| PA 6 days | 0.21 | 1.24 (1.16–1.32) | <0.001 | |

| PA 7 days | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| About every month | PA 0 days | 0.09 | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | 0.010 |

| PA 1 days | 0.28 | 1.32 (1.24–1.40) | <0.001 | |

| PA 2 days | 0.33 | 1.39 (1.32–1.46) | <0.001 | |

| PA 3 days | 0.29 | 1.34 (1.28–1.40) | <0.001 | |

| PA 4 days | 0.29 | 1.33 (1.27–1.40) | <0.001 | |

| PA 5 days | 0.26 | 1.30 (1.24–1.36) | <0.001 | |

| PA 6 days | 0.21 | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) | <0.001 | |

| PA 7 days | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Low Mood Category a | Variable Predictor | Beta | OR (95% IC) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| About every day | BI—Much too thin | −1.09 | 0.33 (0.29–0.37) | <0.001 |

| BI—Bit too thin | −1.75 | 0.17 (0.15–0.19) | <0.001 | |

| BI—About right | −2.11 | 0.12 (0.11–0.13) | <0.001 | |

| BI—Bit too fat | −1.26 | 0.28 (0.25–0.30) | <0.001 | |

| BI—Much too fat | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| More than once/week | BI—Much too thin | −0.81 | 0.44 (0.32–0.50) | <0.001 |

| BI—Bit too thin | −1.07 | 0.34 (0.30–0.37) | <0.001 | |

| BI—About right | −1.34 | 0.26 (0.23–0.28) | <0.001 | |

| BI—Bit fat | −0.67 | 0.50 (0.46–0.55) | <0.001 | |

| BI—Much too fat | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| About every week | BI—Much too thin | −0.58 | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) | <0.001 |

| BI—Bit too thin | −0.57 | 0.56 (0.50–0.62) | <0.001 | |

| BI—About right | −0.85 | 0.42 (0.38–0.46) | <0.001 | |

| BI—Bit too fat | −0.33 | 0.71 (0.64–0.79) | <0.001 | |

| BI—Much too fat | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| About every month | BI—Much too thin | −0.45 | 0.63 (0.56–0.71) | <0.001 |

| BI—Bit too thin | −0.26 | 0.76 (0.69–0.84) | <0.001 | |

| BI—About right | −0.40 | 0.66 (0.60–0.73) | <0.001 | |

| BI—Bit too fat | −0.10 | 0.90 (0.82–0.99) | 0.03 | |

| BI—Much too fat | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Low Mood Category a | Variable Predictor | Beta | OR (95% IC) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| About every day | Age | 0.19 | 1.21 (1.20–1.23) | <0.001 |

| Male | −0.90 | 0.40 (0.38–0.42) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI—thinness | 0.27 | 1.32 (1.16–1.49) | <0.001 | |

| BMI—normal weight | 0.25 | 1.29 (1.15–1.44) | <0.001 | |

| BMI—overweight | 0.17 | 1.19 (1.06–1.34) | 0.003 | |

| BMI—obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| More than once/week | Age | 0.18 | 1.20 (1.18–1.21) | <0.001 |

| Male | −0.75 | 0.46 (0.45–0.48) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI—thinness | 0.18 | 1.19 (1.06–1.34) | 0.002 | |

| BMI—normal weight | 0.18 | 1.20 (1.08–1.33) | <0.001 | |

| BMI—overweight | 0.08 | 1.09 (0.97 -1.21) | 0.114 | |

| BMI—obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| About every week | Age | 0.15 | 1.16 (1.15–1.17) | <0.001 |

| Male | −0.53 | 0.58 (0.56–0.60) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI—thinness | 0.17 | 1.18 (1.05–1.32) | 0.003 | |

| BMI—normal weight | 0.23 | 1.26 (1.14 -1.40) | <0.001 | |

| BMI—overweight | 0.13 | 1.14 (1.02 -1.27) | 0.016 | |

| BMI—obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| About every month | Age | 0.09 | 1.10 (1.09–1.11) | <0.001 |

| Male | −0.25 | 0.77 (0.75–0.79) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI—thinness | 0.22 | 1.24 (1.13–1.37) | <0.001 | |

| BMI—normal weight | 0.20 | 1.23 (1.12–1.34) | <0.001 | |

| BMI—overweight | 0.12 | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) | <0.001 | |

| BMI—obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melo, G.L.R.; Alves Maciel, L.; Espírito Santo, R.; Brand, C.; Reuter, C.P.; Razbadauskas, A.; Rauckienė-Michaelsson, A.; Agostinis-Sobrinho, C. Physical Activity as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Body Image Perception and Low Mood in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020288

Melo GLR, Alves Maciel L, Espírito Santo R, Brand C, Reuter CP, Razbadauskas A, Rauckienė-Michaelsson A, Agostinis-Sobrinho C. Physical Activity as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Body Image Perception and Low Mood in Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020288

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelo, Geiziane Leite Rodrigues, Larissa Alves Maciel, Rafaela Espírito Santo, Caroline Brand, Cézane Priscila Reuter, Artūras Razbadauskas, Alona Rauckienė-Michaelsson, and Cesar Agostinis-Sobrinho. 2025. "Physical Activity as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Body Image Perception and Low Mood in Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020288

APA StyleMelo, G. L. R., Alves Maciel, L., Espírito Santo, R., Brand, C., Reuter, C. P., Razbadauskas, A., Rauckienė-Michaelsson, A., & Agostinis-Sobrinho, C. (2025). Physical Activity as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Body Image Perception and Low Mood in Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020288