Exploring Physical Activity Engagement and Related Variables During Pregnancy and Postpartum and the Best Practices for Self-Report Physical Activity Postpartum

Abstract

1. Women Moving Forward: Exploring Physical Activity Engagement During Pregnancy and Postpartum

2. Method

2.1. Recruitment and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Information

2.2.2. Physical Activity

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Physical Activity from Pregnancy to Postpartum

3.2.1. Pregnancy

3.2.2. Postpartum

3.3. Physical Activity and Associated Variables

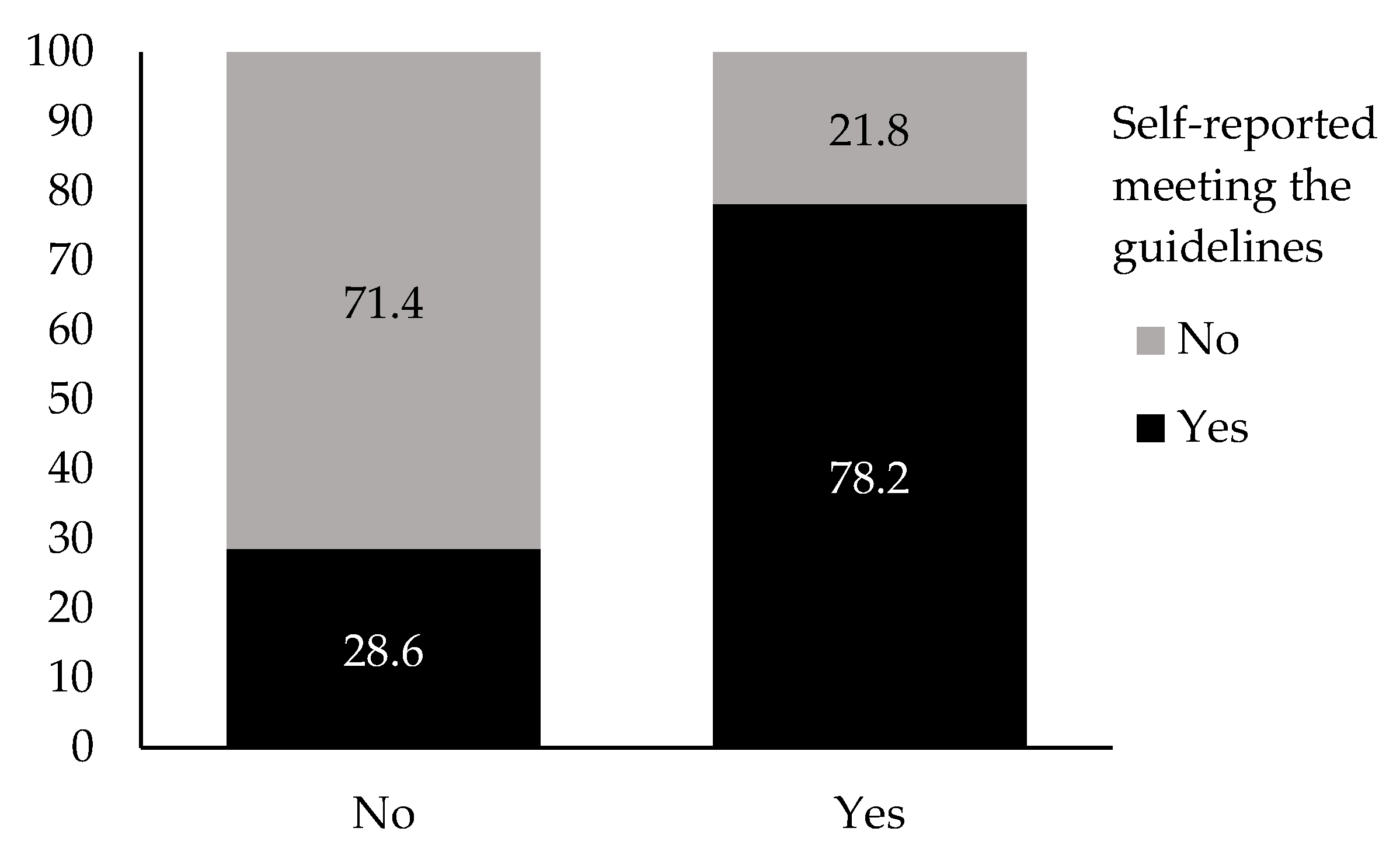

3.4. Reliability of Participants’ Physical Activity Estimation

4. Discussion

4.1. Reliability of Participants’ Physical Activity Estimation

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Directions

4.3. Implications for Practice and/or Policy

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dipietro, L.; Evenson, K.R.; Bloodgood, B.; Sprow, K.; Troiano, R.; Piercy, K.L.; Vaux-Bjerke, A.; Powell, K.E.; 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Benefits of Physical Activity during Pregnancy and Postpartum: An Umbrella Review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M.H.; Ruchat, S.-M.; Garcia, A.J.; Ali, M.U.; Forte, M.; Beamish, N.; Fleming, K.; Adamo, K.B.; Brunet-Pagé, É.; Chari, R.; et al. 2025 Canadian guideline for physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep throughout the first year post partum. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, 59, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruchat, S.-M.; Beamish, N.; Pellerin, S.; Usman, M.; Dufour, S.; Meyer, S.; Sivak, A.; Davenport, M.H. Impact of exercise on musculoskeletal pain and disability in the postpartum period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, 59, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, E.; Sherburn, M.; Osborne, R.H.; Galea, M.P. An Exercise and Education Program Improves Well-Being of New Mothers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Maternal and Newborn Care for a Positive Postnatal Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasinghe, M.; Herath, M.P.; Hills, A.P.; Ahuja, K.D.K. Postpartum versus postnatal period: Do the name and duration matter? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Herring, A.H.; Wen, F. Self-Reported and Objectively Measured Physical Activity Among a Cohort of Postpartum Women: The PIN Postpartum Study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2012, 9, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.H.; Padmapriya, N.; Tan, S.L.; Goh, C.M.J.; Chong, Y.-S.; Shek, L.P.; Tan, K.H.; Gluckman, P.D.; Yap, F.K.; Lee, Y.S.; et al. Longitudinal Analysis of Patterns and Correlates of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Women from Preconception to Postpartum: The Singapore Preconception Study of Long-Term Maternal and Child Outcomes Cohort. J. Phys. Act. Health 2023, 20, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vivo, M.; Mills, H. “They turn to you first for everything”: Insights into midwives’ perspectives of providing physical activity advice and guidance to pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Shields, N.; Frawley, H.C. Attitudes, barriers and enablers to physical activity in pregnant women: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2018, 64, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findley, A.; Smith, D.M.; Hesketh, K.; Keyworth, C. Exploring womens’ experiences and decision making about physical activity during pregnancy and following birth: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, F.; Davis, K. Factors that influence physical activity for pregnant and postpartum women and implications for primary care. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2011, 17, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keepanasseril, A.; Singh, S.; Bharadwaj, B. Postpartum Mental Health Status & Role Transition to Mother in Primigravid Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2023, 41, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ritondo, T.; Bean, C.; Lesser, I. ‘I didn’t know who to ask about how it should feel’: Postpartum women navigating the return to physically active leisure. Leisure/Loisir 2024, 48, 475–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, I.A.; Nienhuis, C.P.; Hatfield, G.L. Moms on the move: A qualitative exploration of a postpartum group exercise program on physical activity behaviour at three distinct time points. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2172793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodulin, K.; Evenson, K.R.; Herring, A.H. Physical activity patterns during pregnancy through postpartum. BMC Women’s Health 2009, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R. Towards an understanding of change in physical activity from pregnancy through postpartum. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baattaiah, B.A.; Zedan, H.S.; Almasaudi, A.S.; Alashmali, S.; Aldhahi, M.I. Physical activity patterns among women during the postpartum period: An insight into the potential impact of perceived fatigue. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.F.; Hesketh, K.R.; Crozier, S.R.; Baird, J.; Godfrey, K.M.; Harvey, N.C.; Westgate, K.; Inskip, H.M.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. The association between number and ages of children and the physical activity of mothers: Cross-sectional analyses from the Southampton Women’s Survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, S.V.; Skejø, S.D.; Nielsen, R.O.; Ryom, K.; Kallestrup, P.; Elsborg, P.; Petersen, C.B.; Jacobsen, J.S. Danish mothers of young children adhere less to international physical activity guidelines compared with mothers of older children. Prev. Med. Rep. 2025, 50, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, S.; Nielsen, R.; Kallestrup, P.; Ryom, K.; Morgan, K.; Elsborg, P.; Petersen, C.; Jacobsen, J. Parous women perform less moderate to vigorous physical activity than their nulliparous peers: A population-based study in Denmark. Public Health 2024, 231, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Wen, F.; Herring, A.H.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Evenson, K.R. Perception and reality: The mismatch between absolute and relative physical activity intensity during pregnancy and postpartum in United States women. Prev. Med. 2024, 182, 107948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Herrmann, S.D.; Meckes, N.; Bassett, D.R.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Greer, J.L.; Vezina, J.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Leon, A.S. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.H.; Meyer, S.; Meah, V.L.; Strynadka, M.C.; Khurana, R. Moms Are Not OK: COVID-19 and Maternal Mental Health. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2020, 1, 561147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 12th ed.; American College of Sports Medicine: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2017, 42, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Evenson, K.R. Prevalence of U.S. Pregnant Women Meeting 2015 ACOG Physical Activity Guidelines. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, e87–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, M.; Amare Tesfa, N.; Nigatu, A.; Tunta, A.; Seyoum, Z.; Derbew, T. Physical activity during pregnancy and pregnancy related complication. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; van den Akker, O. A systematic review of changes in women’s physical activity before and during pregnancy and the postnatal period. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2015, 33, 325–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Adamo, K.; Rhodes, R.E. Associations of Parenthood with Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Sleep. Am. J. Health Behav. 2018, 42, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadeta, T.; Belema, D.; Ahmad, S.; Sirage, N.; Ali, A.S.; Ali, K.; Yimer, A. Assessment of post-partum physical exercise practice and its associated factors among women in postpartum period, in West Wollega zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1505303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meah, V.L.; Davies, G.A.; Davenport, M.H. Why can’t I exercise during pregnancy? Time to revisit medical ‘absolute’ and ‘relative’ contraindications: Systematic review of evidence of harm and a call to action. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottola, M.F.; Davenport, M.H.; Ruchat, S.-M.; Davies, G.A.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Garcia, A.J.; Barrowman, N.; Adamo, K.B.; Duggan, M.; et al. Canadian Guidelines for Physical Activity Throughout Pregnancy. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borodulin, K.M.; Evenson, K.R.; Wen, F.; Herring, A.H.; Benson, A.M. Physical Activity Patterns during Pregnancy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evenson, K.R.; Aytur, S.A.; Borodulin, K. Physical activity beliefs, barriers, and enablers among postpartum women. J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 1925–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saligheh, M.; McNamara, B.; Rooney, R. Perceived barriers and enablers of physical activity in postpartum women: A qualitative approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, I.A.; Turgeon, S.; Nienhuis, C.P.; Bean, C. Examining the Role of Physical Activity on Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health Postpartum. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2023, 31, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.K.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Frizzelle, B.G.; Evenson, K.R. The Association between Neighborhood Environments and Physical Activity from Pregnancy to Postpartum: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Urban Health 2019, 96, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Family Database. Parental Leave Systems; OECD Family Database: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, C.; Lesser, I. Increasing health equity for postpartum women through physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2024, 21, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornquist, L.; Tornquist, D.; Mielke, G.I.; da Silveira, M.F.; Hallal, P.C.; Domingues, M.R. Maternal Physical Activity Patterns in the 2015 Pelotas Birth Cohort: From Preconception to Postpartum. J. Phys. Act. Health 2023, 20, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, N.; Bergman, L.; Smith, G.N. Pregnancy-associated cardiovascular risks and postpartum care; an opportunity for interventions aiming at health preservation and disease prevention. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 92, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, S.; Sinclair, M.; Murphy, M.H.; Madden, E.; Dunwoody, L.; Liddle, D. Reducing the Decline in Physical Activity during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Behaviour Change Interventions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Met Guidelines Postpartum | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Postpartum period | Met guidelines during pregnancy | n (%) | n (%) |

| <12 weeks | No | 114 (91.2) | 11 (8.8) |

| Yes | 25 (55.6) | 20 (44.4) | |

| 12–24 weeks | No | 89 (80.2) | 22 (19.8) |

| Yes | 17 (43.6) | 22 (56.4) | |

| >24 weeks | No | 110 (79.7) | 28 (20.3) |

| Yes | 32 (53.3) | 28 (46.7) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turgeon, S.; Lesser, I.; Bean, C. Exploring Physical Activity Engagement and Related Variables During Pregnancy and Postpartum and the Best Practices for Self-Report Physical Activity Postpartum. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111711

Turgeon S, Lesser I, Bean C. Exploring Physical Activity Engagement and Related Variables During Pregnancy and Postpartum and the Best Practices for Self-Report Physical Activity Postpartum. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111711

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurgeon, Stephanie, Iris Lesser, and Corliss Bean. 2025. "Exploring Physical Activity Engagement and Related Variables During Pregnancy and Postpartum and the Best Practices for Self-Report Physical Activity Postpartum" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111711

APA StyleTurgeon, S., Lesser, I., & Bean, C. (2025). Exploring Physical Activity Engagement and Related Variables During Pregnancy and Postpartum and the Best Practices for Self-Report Physical Activity Postpartum. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111711