Wood Odor Mapping on Arousal Axes: Exploring Correspondence with Physiological Indices of Stress Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods Introduction

2.1. Study Design

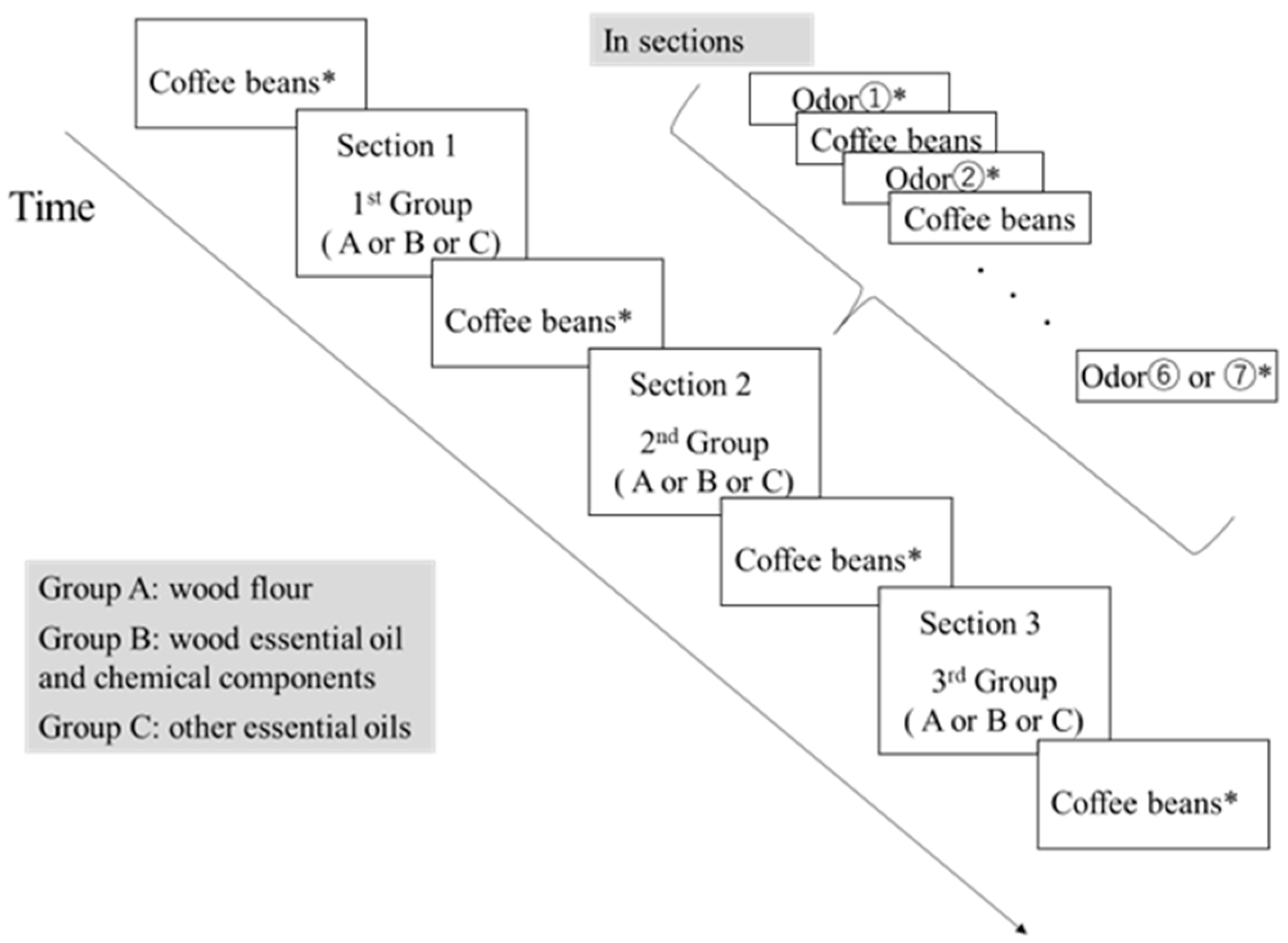

2.2. Experiment 1

2.2.1. Overview

2.2.2. Types of Stimuli

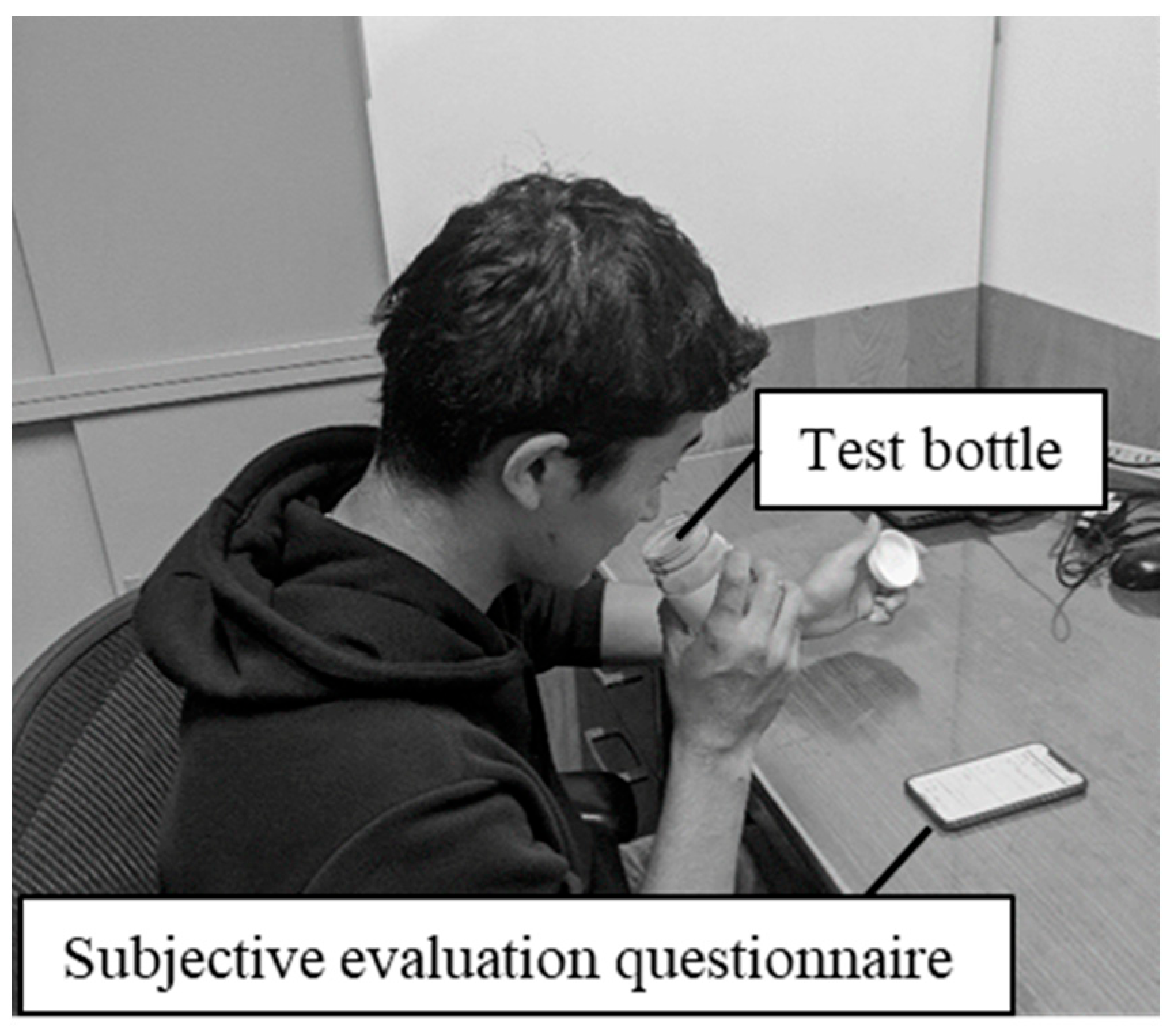

2.2.3. Subjective Evaluations

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

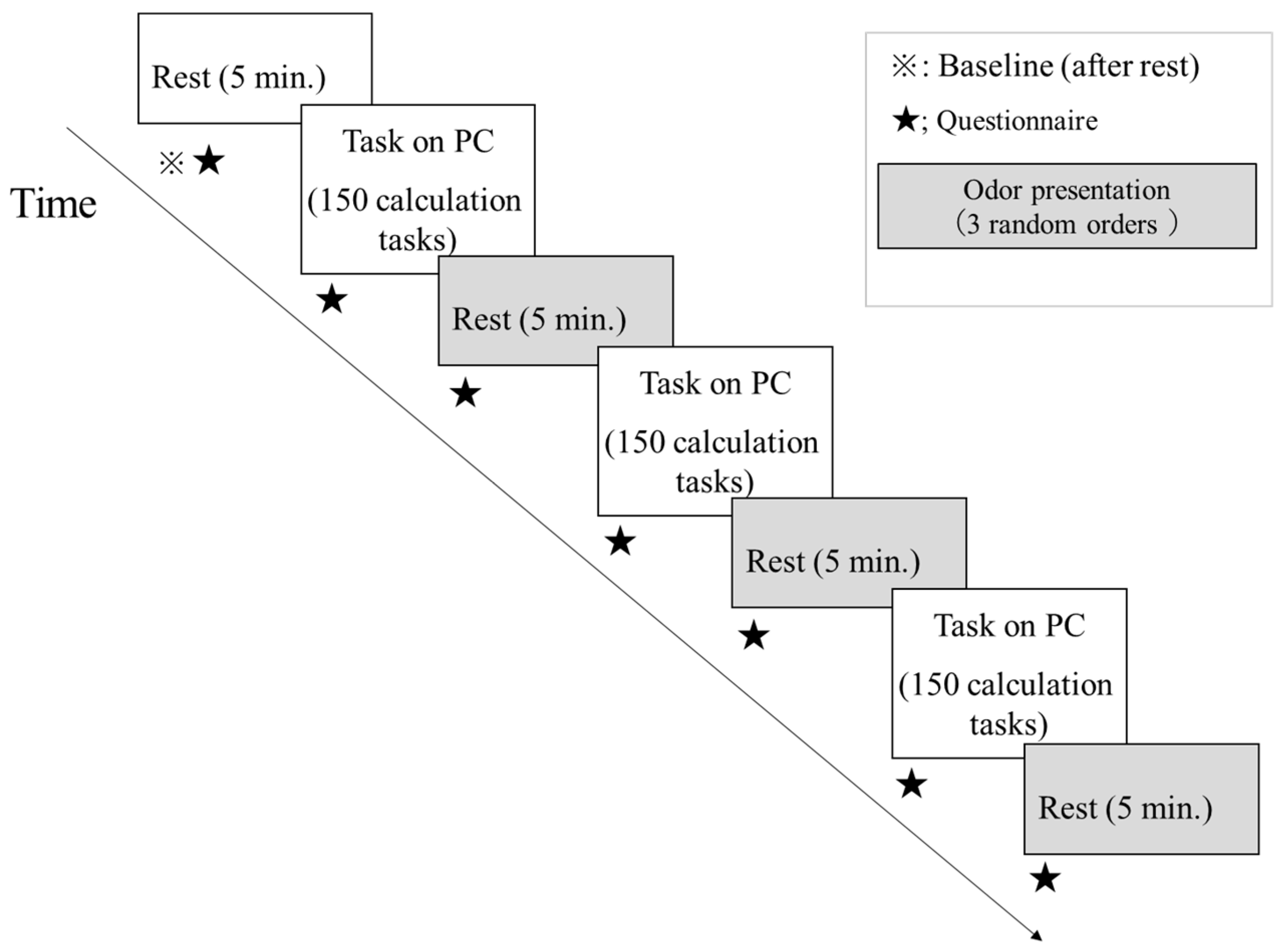

2.3. Experiment 2

2.3.1. Overview

2.3.2. Odor Presentation

2.3.3. Measurements

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

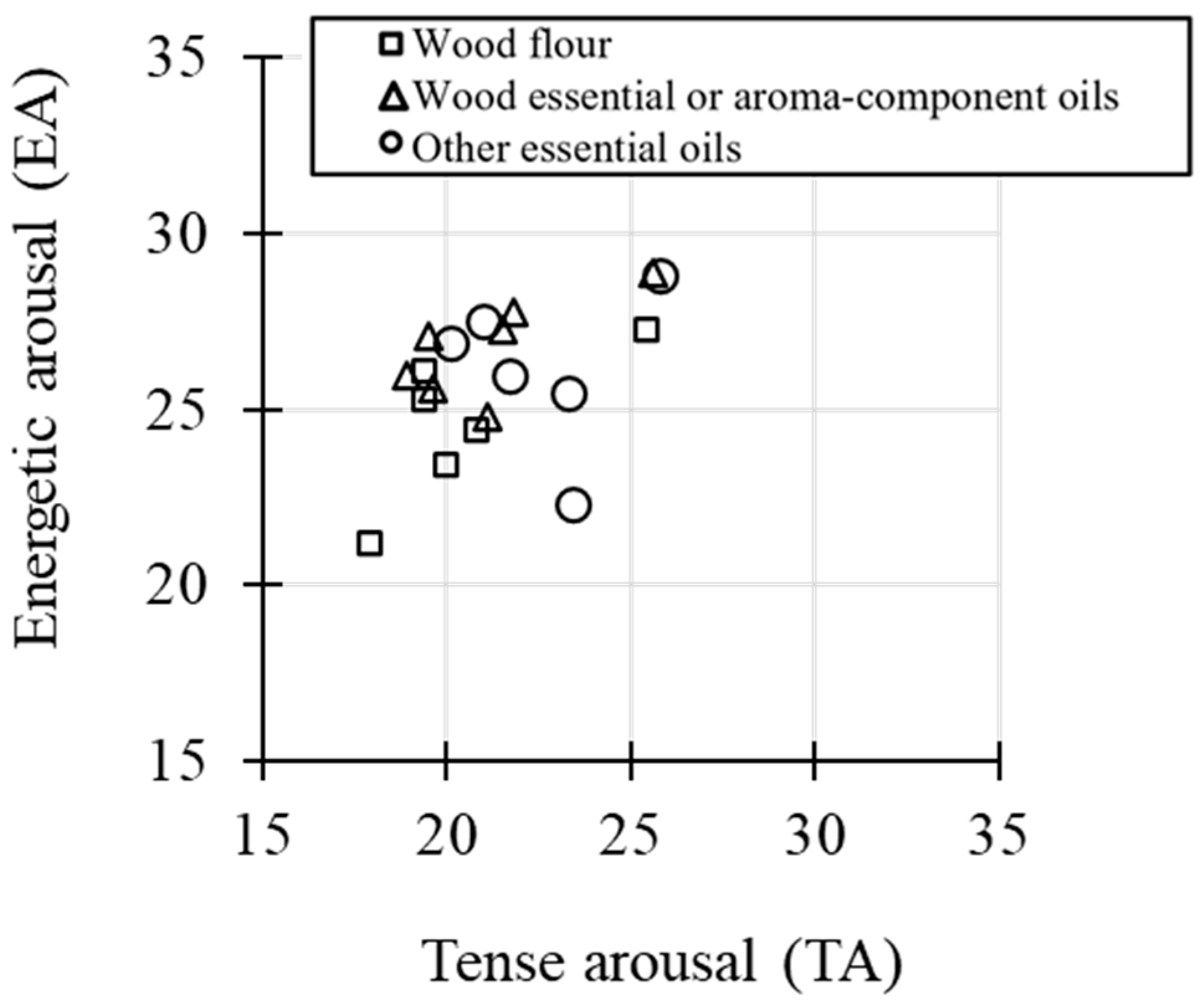

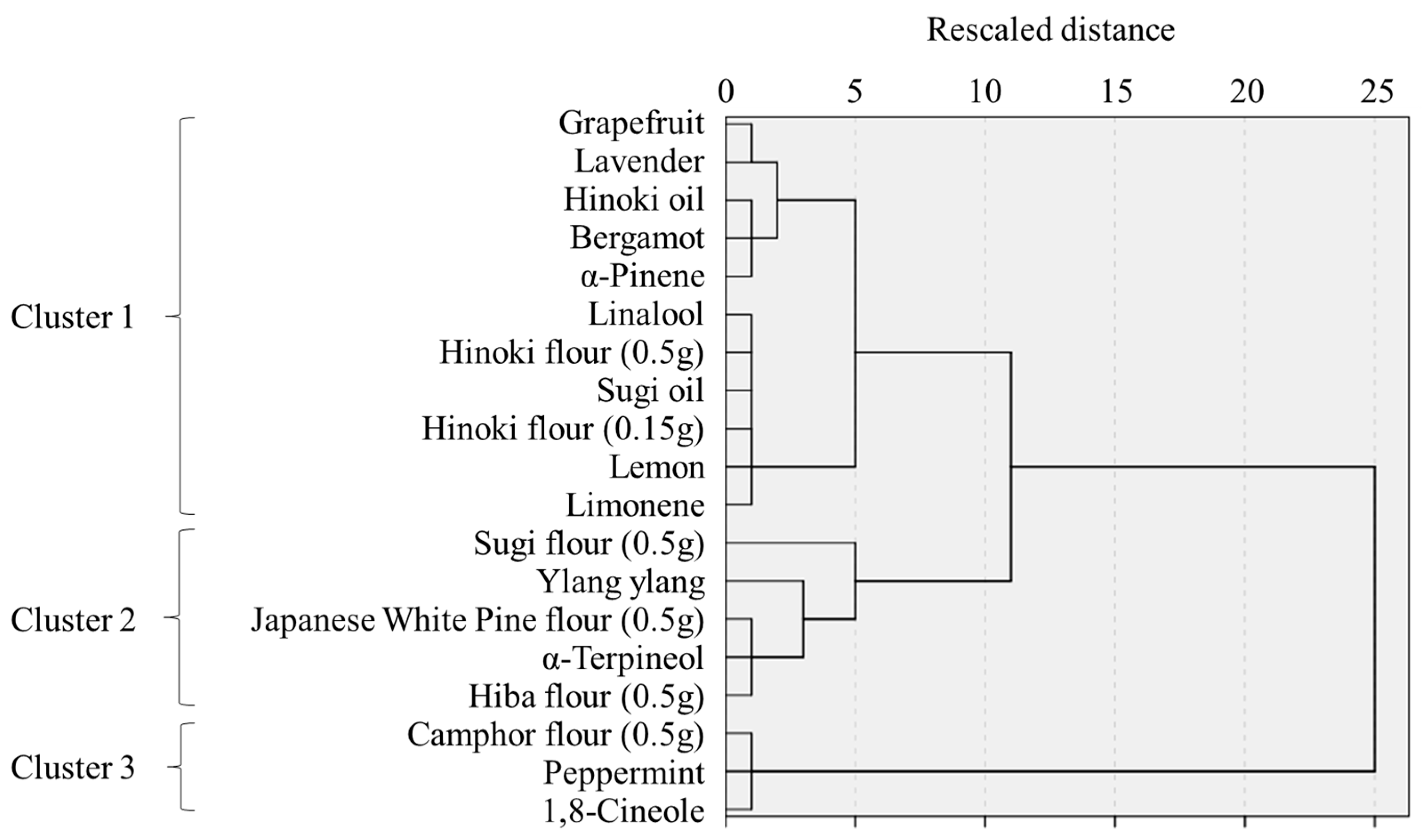

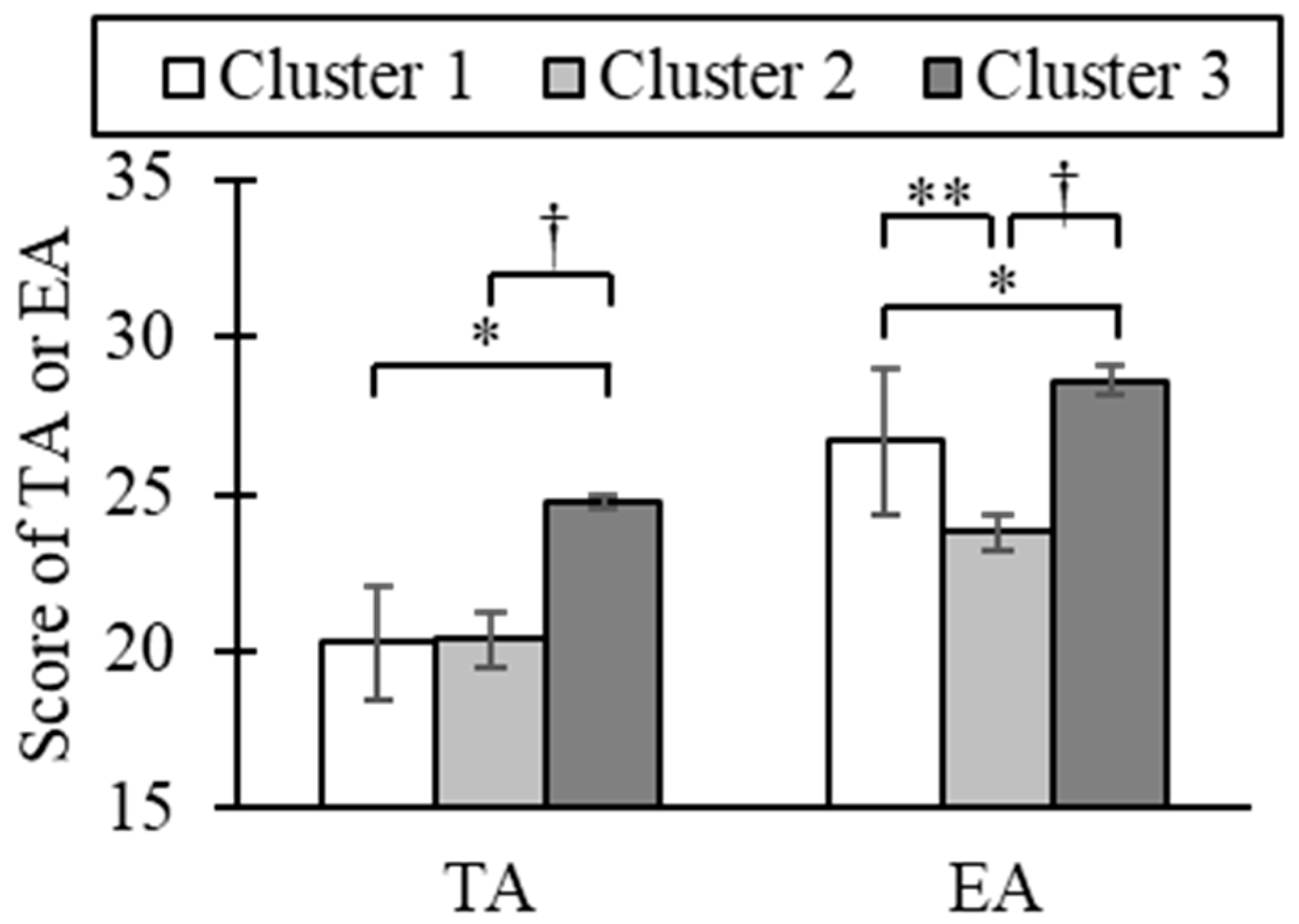

3.1. Mapping Odor Responses on Arousal Axes (Experiment 1)

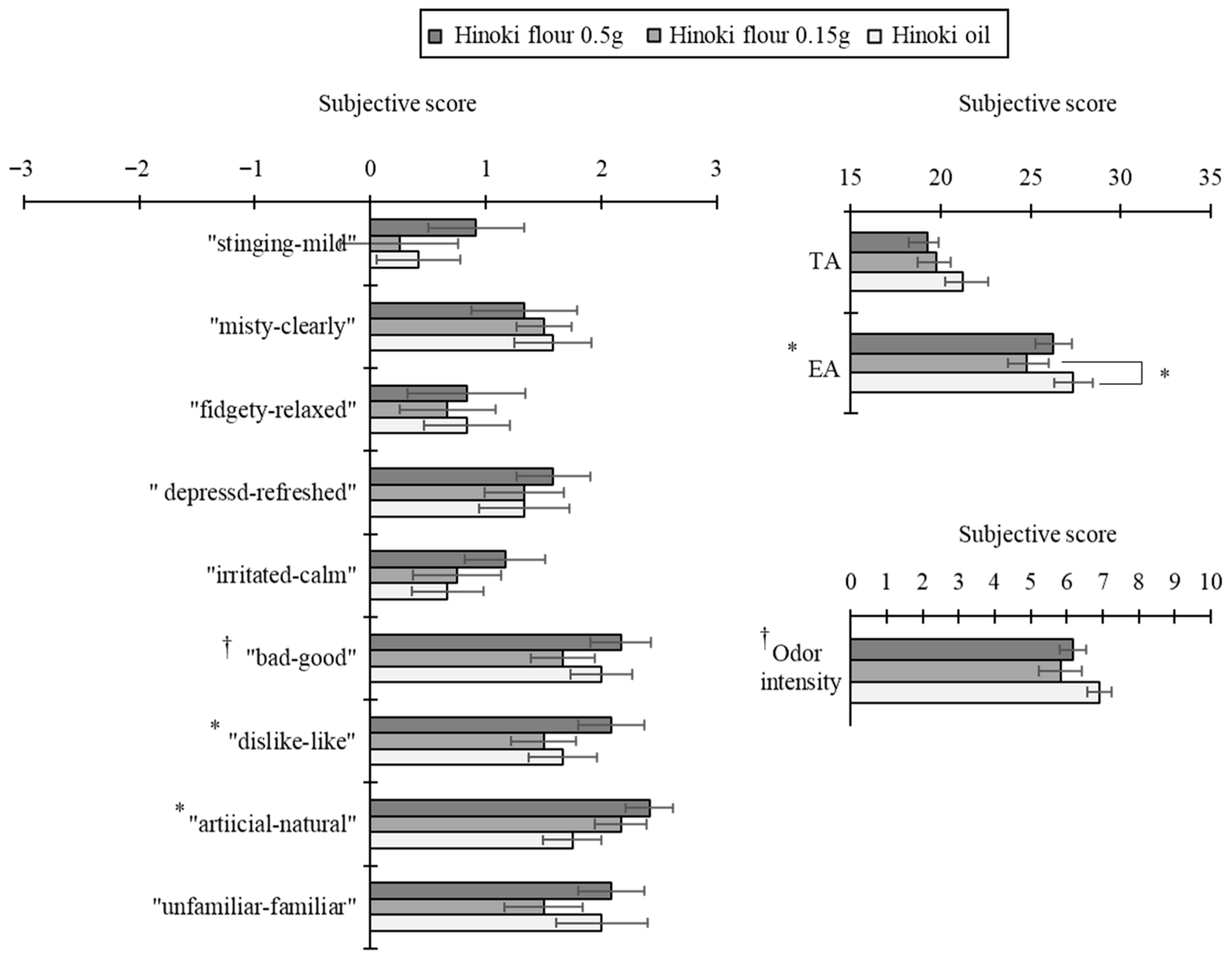

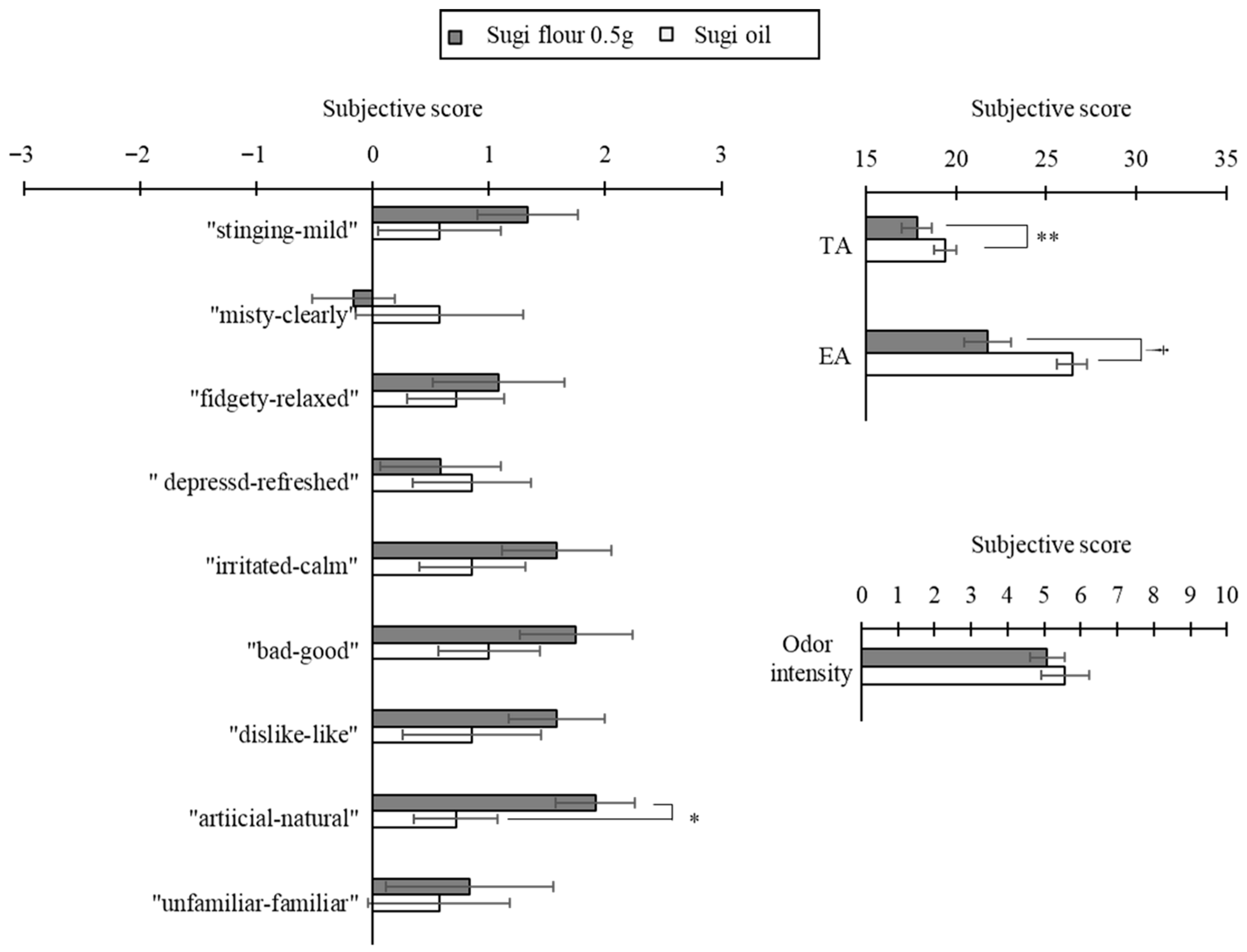

3.2. Within-Species Comparisons (Experiment 1)

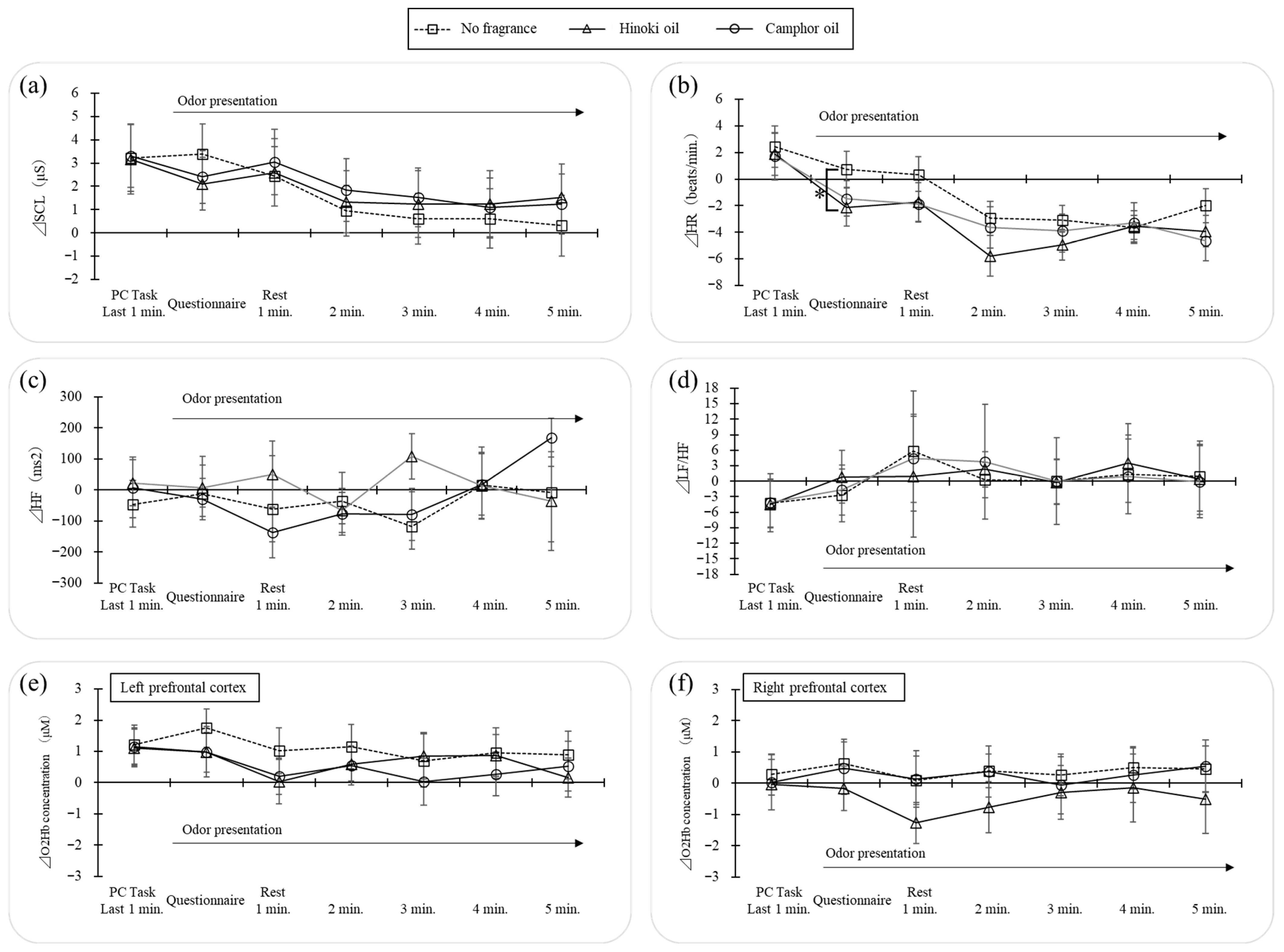

3.3. Physiological Responses During Rest Periods (Experiment 2)

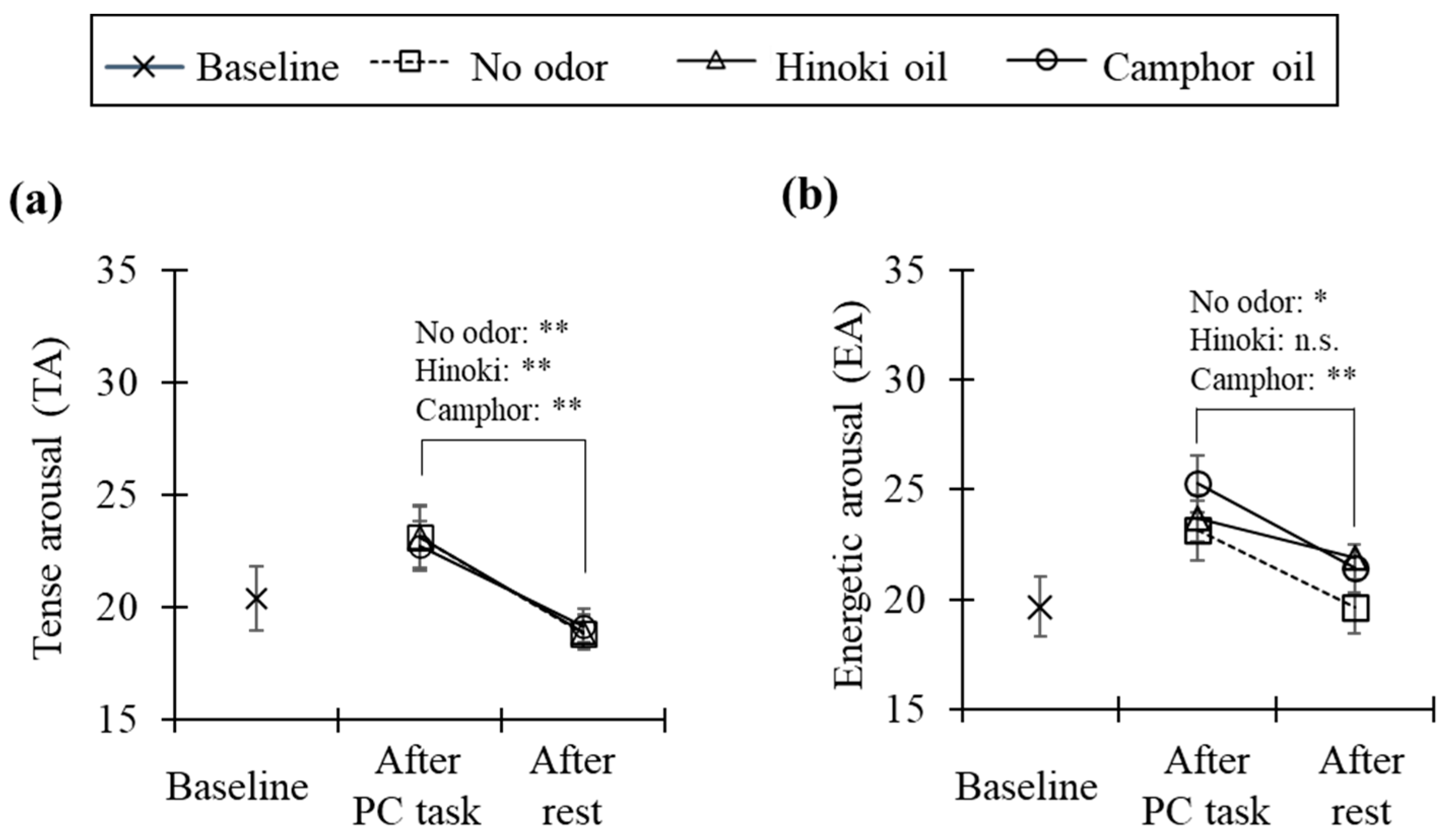

3.4. Subjective Arousal (Experiment 2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Larsen, F.B.; Lasgaard, M.; Willert, M.V.; Sørensen, J.B. Estimating the causal effects of work-related and non-work-related stressors on perceived stress level: A fixed effects approach using population-based panel data. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan). Outline of the Results of the 2021 Survey on Industrial Safety and Health (Actual Conditions Survey). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/r03-46-50b.html (accessed on 15 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; Available online: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA22551329 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Crawford, R.H.; Cadorel, X. A Framework for Assessing the Environmental Benefits of Mass Timber Construction. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnar, M.D.; Kutnar, A. Wood and human stress in the built indoor environment: A review. Wood Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of wood on humans: A review. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovac, D.; Burnard, M.D. Effects of visual exposure to wood on human affective states, physiological arousal and cognitive performance: A systematic review of randomized trials. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 30, 1021–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamic, D.; Domljan, D. Positive Aspects of Using Solid Wood in Interiors on Human Wellbeing: A Review. Drv. Ind. 2023, 74, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyrud, A.Q.; Bringslimark, T. Is Interior Wood Use Psychologically Beneficial? A Review of Psychological Responses Toward Wood. Wood Fiber Sci. 2010, 42, 202–218. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, E.; Kawai, S. Gender differences in the psychophysiological effects induced by VOCs emitted from Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica). Environ. Health Prev. 2018, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Kumar, K.J.S.; Chen, Y.-T.; Tsao, N.-W.; Chien, S.-C.; Chang, S.-T.; Chu, F.-H.; Wang, S.-Y. Effect of Hinoki and Meniki Essential Oils on Human Autonomic Nervous System Activity and Mood States. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1305–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Yang, Y.; Xu, T.; Yao, D.; Lin, S.; Chang, W. Assessing the Anxiolytic and Relaxation Effects of Cinnamomum camphora Essential Oil in University Students: A Comparative Study of EEG, Physiological Measures, and Psychological Responses. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1423870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, E.; Matsui, N.; Ohira, T. Evaluation of the psychophysiological effects of the Cupressaceae family wood odor. Wood Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Effects of olfactory stimulation by α-pinene on autonomic nervous activity. J. Wood Sci. 2016, 62, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, E.; Kawai, S. VOCs emitted from Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) interior walls induce physiological relaxation. Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P.; Weng, W.-C.; Ramanpong, J.; Wu, C.-D.; Tsai, M.-J.; Spengler, J.D. Physiological and psychological responses to olfactory simulation by Taiwania (Taiwania cryptomerioides) essential oil and the influence of cognitive bias. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, T.; Sakata, K.; Tsunetsugu, Y. Subjective Interactions of Wood-Derived Olfactory and Visual Stimuli During Work and Rest. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, F.; Tani, K.; Nakashima, T.; Zennifa, F.; Isa, A.; Fujimoto, N.; Fujita, K.; Taki, R.; Yasutomi, H.; Yasumori, N.; et al. A pilot study on physiological relaxation and enhanced work performance by volatile organic compounds emitted from Kagawa Hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa) interior walls. J. Wood Sci. 2025, 71, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, T.; Maeda, K.; Tsunetsugu, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of scent introduction in monotonous tasks: A model experiment of combined stress close to real-life situations. Jpn. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2020, 25, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, R.E. Moods of Energy and Tension That Motivate. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation; Ryan, R.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.; Jones, D.M.; Chamberlain, A.G. Refining the measurement of mood: The UWIST Mood Adjective Checklist. Br. J. Psychol. 1990, 81, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakata, T.; Saito, M. Psychological study on classification of odors: Classification of odors by impressions using the SD method. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Kansei Eng. 2014, 13, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ayabe, S. Methods for presenting odor stimuli in psychological experiments. Jpn. J. Res. Emot. 2005, 12, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H.; Kaneko, T. Evaluation of wood measured using odor as a scale: Preference ratings for odors and EEG findings. Mokuzai Kogyo (Wood Ind.) 1995, 50, 266–268. Available online: https://u-ryukyu.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/2002093 (accessed on 13 September 2007). (In Japanese).

- Iwasaki, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Watanabe, M. Stress-relieving effects of volatile components of urban greening trees: An experiment using camphor tree. Aroma Res. 2004, 5, 386–390. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Odor Control Administrative Guidebook, April 2002. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/air/akushu/guidebook/full.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Shirasawa, S.; Ishida, T.; Hakoda, H.; Haraguchi, M. Effects of energetic arousal on memory search. Jpn. J. Psychon. Sci. 1999, 17, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T.; Shoji, K.; Hatayama, T. A psychological study of sensory adjectives describing fragrances. Jpn. J. Res. Emot. 2002, 8, 45–59. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lian, Z.; Ding, Q. Investigation variance in human psychological responses to wooden indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2016, 109, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, E.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ohira, T.; Sugiyama, M. Essential Oil of Japanese Cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) Wood Increases Salivary Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate Levels after Monotonous Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, M.; Torki-Harchegani, M.; Pirbalouti, A.G. Quantity and chemical composition of essential oil of peppermint (Mentha × piperita L.) leaves under different drying methods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.-X.; Lin, J.-G.; Liu, J.; Jiang, M.-S.; Chu, L.-X. Chemical Composition and Antifungal Activity of Extracts from the Xylem of Cinnamomum camphora. BioResources 2014, 9, 2560–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principal Component Scores | Arousal Levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | TA | EA | ||

| Wood flours | Hinoki (0.5 g) | 8.3 | 11.0 | 19.3 | 26.3 |

| Hinoki (0.15 g) | 6.8 | 9.8 | 19.2 | 25.4 | |

| Hiba | 4.1 | 6.3 | 20.5 | 24.7 | |

| Camphor | −3.5 | 9.1 | 24.3 | 27.8 | |

| Sugi | 9.7 | 6.8 | 17.8 | 21.8 | |

| Japanese White Pine | 6.9 | 6.9 | 19.8 | 23.7 | |

| Wood essential oils or chemical components | Sugi oil | 4.8 | 6.9 | 19.4 | 26.4 |

| Hinoki oil | 5.5 | 10.9 | 21.3 | 27.3 | |

| α-Pinene | 1.5 | 7.7 | 21.2 | 27.1 | |

| Limonene | 4.7 | 9.6 | 19.3 | 27.3 | |

| 1,8-Cineole | −8.4 | 9.0 | 25.0 | 28.5 | |

| Linalool | 4.3 | 9.3 | 18.8 | 25.9 | |

| α-Terpineol | 0.6 | 5.2 | 20.8 | 25.3 | |

| Other essential oils | Bergamot | 3.3 | 9.6 | 20.8 | 27.5 |

| Lavender | 0.1 | 7.2 | 22.8 | 26.2 | |

| Lemon | 3.0 | 10.2 | 20.0 | 27.6 | |

| Peppermint | −6.9 | 11.0 | 25.0 | 29.6 | |

| Ylang ylang | 0.3 | 4.3 | 23.2 | 23.6 | |

| Grapefruit | 3.0 | 11.3 | 21.3 | 26.8 | |

| Impressions | Arousal Levels | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| 1. Intensity | −0.87 ** | 0.54 * | −0.86 ** | 0.40 | −0.89 ** | −0.57 * | −0.57 * | −0.65 ** | 0.03 | 0.95 ** | 0.60 ** | |

| 2. “stinging -mild” | −0.63 ** | 0.87 ** | −0.36 | 0.90 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.09 | −0.87 ** | −0.61 ** | ||

| 3. “misty -clear” | −0.42 | 0.89 ** | −0.63 ** | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.31 | 0.54 * | 0.40 | 0.90 ** | |||

| 4. “fidgety -relaxed” | −0.23 | 0.86 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.78 ** | 0.27 | −0.90 | −0.47 * | ||||

| 5. “depressed -refreshed” | −0.38 | 0.21 | 0.31 | −0.08 | 0.68 ** | 0.22 | 0.79 ** | |||||

| 6. “irritated -calm” | 0.73 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.03 | −0.86 ** | −0.68 ** | ||||||

| 7. “bad -good” | 0.94 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.57 * | −0.70 ** | −0.19 | |||||||

| 8. “dislike -like” | 0.72 ** | 0.61 ** | −0.72 ** | −0.13 | ||||||||

| 9. “artificial -natural” | 0.49 * | −0.72 ** | −0.41 | |||||||||

| 10. “unfamiliar -familiar” | −0.18 | 0.38 | ||||||||||

| 11. TA | 0.49 * | |||||||||||

| 12. EA | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shima, T.; Maeda, K.; Tsunetsugu, Y. Wood Odor Mapping on Arousal Axes: Exploring Correspondence with Physiological Indices of Stress Recovery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111716

Shima T, Maeda K, Tsunetsugu Y. Wood Odor Mapping on Arousal Axes: Exploring Correspondence with Physiological Indices of Stress Recovery. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111716

Chicago/Turabian StyleShima, Takashi, Kei Maeda, and Yuko Tsunetsugu. 2025. "Wood Odor Mapping on Arousal Axes: Exploring Correspondence with Physiological Indices of Stress Recovery" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111716

APA StyleShima, T., Maeda, K., & Tsunetsugu, Y. (2025). Wood Odor Mapping on Arousal Axes: Exploring Correspondence with Physiological Indices of Stress Recovery. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111716