Using Citizen Science to Address Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure with Aboriginal Communities in the Far West of South Australia: A Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Prescribing to Address OOPHE

“a holistic, person centred and community-based approach to health and well-being that bridges the gap between clinical and nonclinical supports and services. By drawing on the central tenets of health promotion and disease prevention, it offers a way to mitigate the impacts of adverse social determinants of health and health inequities by addressing nonmedical, health-related social needs... it is recognised as being a means for trusted individuals in clinical and community settings to identify that a person has nonmedical, health-related social needs and to subsequently connect them to nonclinical supports and services within the community.”([10], page 9)

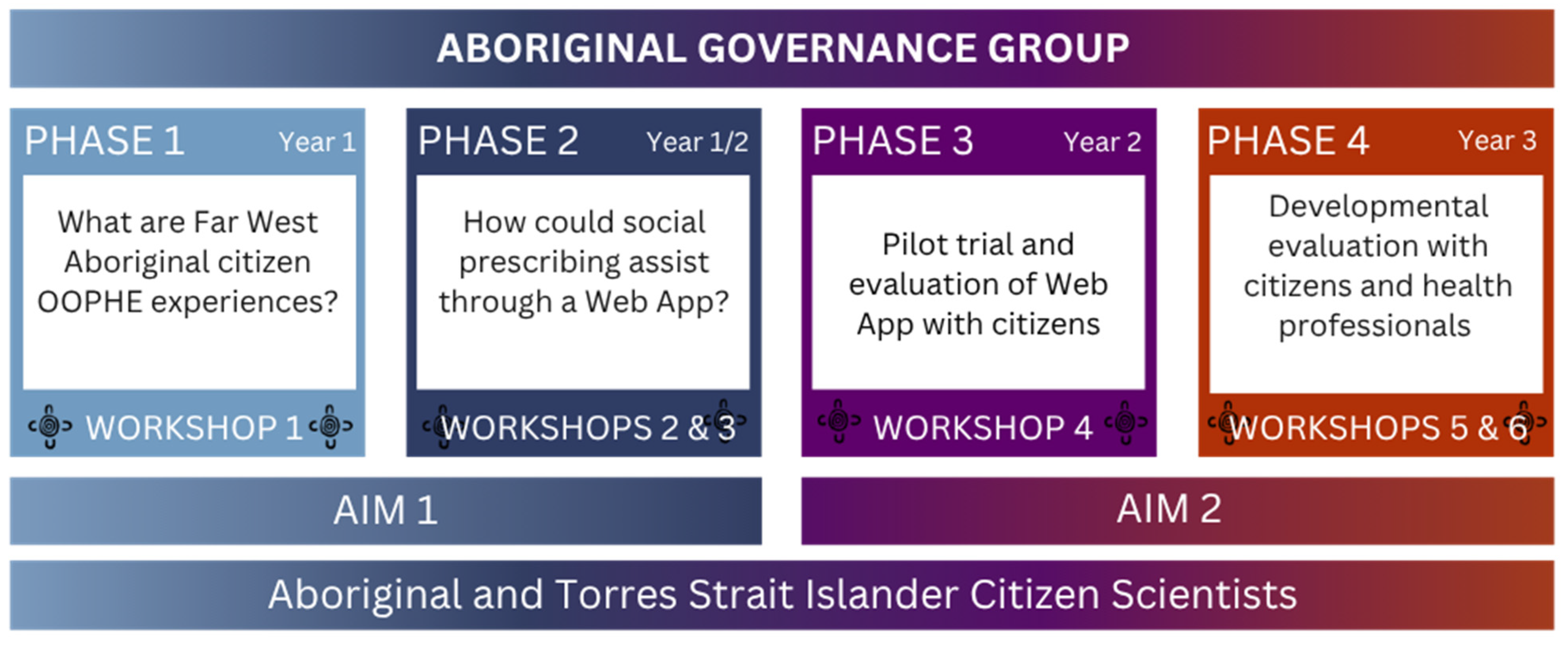

1.2. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Citizen Sciences for Community-Centric Research

2.3. Setting

2.4. Participants

2.5. Citizen Science Governance

2.6. Ethics

2.7. Phase 1: Co-Creation of OOPHE Knowledge

2.8. Phase 2: Web App Co-Design

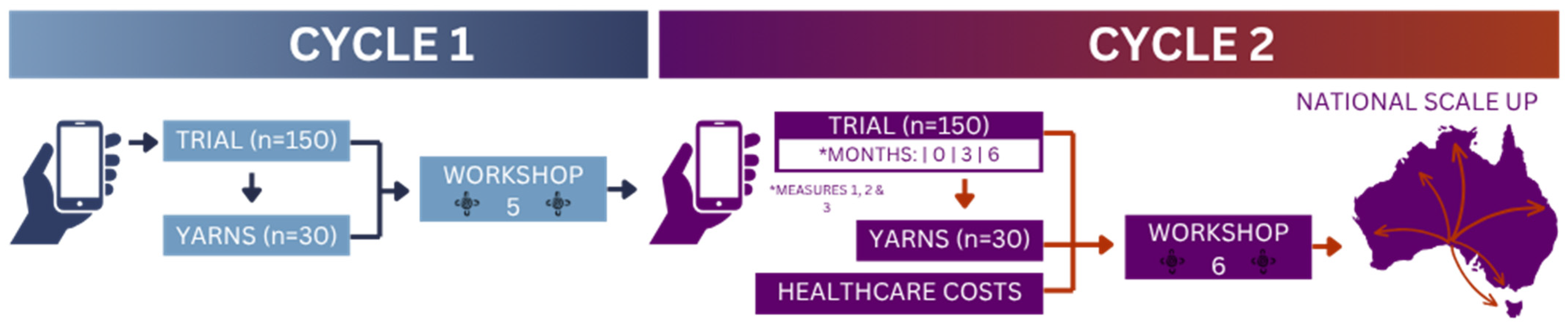

2.9. Phase 3: Web App Pilot

2.10. Phase 4: Web App Evaluation

- Out-of-Pocket Health Expenses (OOPHE), impacts, and associated cultural and social determinants (OOPHE survey) (Primary Outcome)

- Self-management of chronic and complex diseases and injuries (Partners in Health Scale, a chronic condition self-management scale validated in Aboriginal communities)

- Health-Related Quality of Life (assessed using the EQ-5D-5L scale)

2.11. National Scale-Up

2.12. Key Research Outcomes and Impact

2.13. Anticipated Challenges

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OOPHE | Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenses |

| CCD | Chronic and Complex Disease |

| FWCP | Far West Community Partnerships |

| SA | South Australia |

| AGOV | Aboriginal Governance Group |

| NACCHO | National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation |

| CSIRO | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

References

- O’Keeffe, P. Economic Inequality and the ‘Cost of Living’ Crisis, in Power, Privilege and Place in Australian Society; O’Keeffe, P., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, C.; Mackean, T.; Hunter, K.; Coombes, J.; Holland, A.J.; Ivers, R. Yarning up about out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in burns with Aboriginal families. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2021, 45, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Community Affairs References Committee. Senate Report: Out-of-Pocket Costs in Australian Healthcare; Commonwealth: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Callander, E.J.; Corscadden, L.; Levesque, J.-F. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure and chronic disease–do Australians forgo care because of the cost? Aust. J. Prim. Health 2017, 23, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes-Robertson, N.; Gutman, T.; Dominello, A.; Howell, M.; Craig, J.C.; Wong, G.; Jaure, A. Australian Rural Caregivers’ Experiences in Supporting Patients with Kidney Failure to Access Dialysis and Kidney Transplantation: A Qualitative Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 80, 773–782.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckett, S.; Stobart, A.; Lin, L. Not so Universal: How to Reduce Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Payment; Grattan Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, C.; D’Angelo, S.; Sharpe, P.; Mackean, T.; Cominos, N.; Coombes, J.; Bennett-Brook, K.; Cameron, D.; Gloede, E.; Ullah, S.; et al. Experiences and Impacts of Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure on Remote Aboriginal Families in Australia. Rural Remote Health 2024, 24, 8328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: Summary report July 2023; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Kelly, J.; Oliva, D.; Jesudason, S. Indigenous ‘Yarning Kidneys’ Report: Adelaide Consultation; Kidney Health Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muhl, C.; Mulligan, K.; Bayoumi, I.; Ashcroft, R.; Godfrey, C. Establishing internationally accepted conceptual and operational definitions of social prescribing through expert consensus: A Delphi study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, C.; Skelton, C.; Leibbrandt, R.; Bonevski, B. Models of social prescribing to address non-medical needs in adults: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). A toolkit on how to implement social prescribing. In Manila: World health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oster, C.; Gransbury, B.; Anderson, D.; Martin, V.; Skuza, P.; Leibbrandt, R. Development and validation of a self-report social determinants of health questionnaire in Australia. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daac029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health. National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030; Commonwealth of Australia as Represented by the Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Sonke, J.; Manhas, N.; Belden, C.; Morgan-Daniel, J.; Akram, S.; Marjani, S.; Oduntan, O.; Hammond, G.; Martinez, G.; Davidson, C.G.; et al. Social prescribing outcomes: A mapping review of the evidence from 13 countries to identify key common outcomes. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1266429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierala, H.; Krueger, K.; Kuschick, D.; Heintze, C.; Herrmann, W.J.; Holzinger, F. Social Prescribing: Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Psychosocial Community Referral Interventions in Primary Care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2022, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Caruana, T.; Tohmas, T.; Baker, J.R. Social prescribing as an intervention for people with work-related injuries and psychosocial difficulties in Australia. Adv. Health Behav. 2020, 3, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Thomas, T.; Gordon, C.; Bloomfield, J.; Baker, J. Social prescribing for individuals living with mental illness in an Australian community setting: A pilot study. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder, C.; Mackean, T.; Coombs, J.; Williams, H.; Hunter, K.; Holland, A.J.A.; Ivers, R.Q. Indigenous research methodology–weaving a research interface. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2020, 23, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Rushing, A.; Primack, R.; Bonney, R. The history of public participation in ecological research. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M.; Austin, B.J.; Danielsen, F.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á. Creating Synergies Between Citizen Science and Indigenous and Local Knowledge. BioScience 2021, 71, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombes, J.; Ryder, C. Walking together to create harmony in research: A Murri woman’s approach to Indigenous research methodology. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. 2020, 15, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, B. Dark Emu; Hachette: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zurynski, Y.; Vedovi, A.; Smith, K.-l. Social prescribing: A rapid literature review to inform primary care policy in Australia. In Consumers’ Health Forum of Australia; Macquarie University: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research; AIATSIS: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Road Map 3: A Strategic Framework for Improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Through Research; NHMRC: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Wardliparingga. The South Australian Aboriginal Health Landscape Project: Remote Far West, 2019; South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bessarab, D.; Ng’andu, B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 2010, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, C.; Powell, A.; Hutchinson, C.; Anderson, D.; Gransbury, B.; Walton, M.; O’Brien, J.; Raven, S.; Bogomolova, S. The process of co-designing a model of social prescribing: An Australian case study. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelberg, G.R.; Goodman, A.; Musuwadi, C.; Lawler, S.; Caffery, L.J.; Mahoney, R. Towards a best practice framework for eHealth with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples—Important characteristics of eHealth interventions: A narrative review. Med. J. Aust. 2024, 221, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackean, T.; Fisher, M.; Friel, S.; Baum, F. A framework to assess cultural safety in Australian public policy. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, L.; Kohl, R. Scaling up—From Vision to Large-Scale Change: Tools and Techniques for Practitioners; Management System International: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.R. The system usability scale: Past, present, and future. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, A.; Bailie, J.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R. Using developmental evaluation to support knowledge translation: Reflections from a large-scale quality improvement project in Indigenous primary healthcare. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2019, 17, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). South Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population Summary. 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/south-australia-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-population-summary#cite-window1 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Speegle, D.; Clair, B. Probability, Statistics, and Data: A Fresh Approach Using R, 1st ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC Press Texts in Statistical Science; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.L.; Karahalios, A.; Forbes, A.B.; Taljaard, M.; Grimshaw, J.M.; McKenzie, J.E. Comparison of six statistical methods for interrupted time series studies: Empirical evaluation of 190 published series. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Far West Community Partnerships. The Far West Change Agenda; Far West Community Partnerships: Ceduna, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryder, C.; Mahoney, R.; Sharpe, P.; Sallows, G.; Canuto, K.; Goodman, A.; Coombes, J.; Pearson, O.; Hughes, J.T.; Varnfield, M.; et al. Using Citizen Science to Address Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure with Aboriginal Communities in the Far West of South Australia: A Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111640

Ryder C, Mahoney R, Sharpe P, Sallows G, Canuto K, Goodman A, Coombes J, Pearson O, Hughes JT, Varnfield M, et al. Using Citizen Science to Address Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure with Aboriginal Communities in the Far West of South Australia: A Protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111640

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyder, Courtney, Ray Mahoney, Patrick Sharpe, Georga Sallows, Karla Canuto, Andrew Goodman, Julieann Coombes, Odette Pearson, Jaquelyne T. Hughes, Marlien Varnfield, and et al. 2025. "Using Citizen Science to Address Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure with Aboriginal Communities in the Far West of South Australia: A Protocol" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111640

APA StyleRyder, C., Mahoney, R., Sharpe, P., Sallows, G., Canuto, K., Goodman, A., Coombes, J., Pearson, O., Hughes, J. T., Varnfield, M., Oster, C., Karnon, J., Drummond, C., Smith, J. A., Omodei-James, S., Otieno, L., Soltani, A., & Bonevski, B. (2025). Using Citizen Science to Address Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure with Aboriginal Communities in the Far West of South Australia: A Protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111640