Applying Race and Ethnicity in Health Disparities Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Defining Race and Ethnicity

3.2. Historical Context and Evolution of Race and Ethnicity in Society and Science

3.3. Racism

3.4. Race and Biology

3.5. Racial and Ethnic Identity and Genetic Ancestry as Data

3.6. Race and Ethnicity with Health Disparities

3.7. Race and Ethnicity in Clinical Research

4. Discussion

Recommendations for Future Health Disparities Research

5. Conclusions

- Fundamentally recognize and appropriately define race as a social construct.

- Tailor the use of race and ethnicity descriptors to the specific study design and goals.

- Incorporate community involvement in research study design and implementation.

- Strive for extensive racial and ethnic representation in health studies.

- Avoid racial and ethnic categorization for clinical decision-making.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIM | Ancestry Informative Marker |

| CFIR | Consolidated Frameworks for Implementation Research |

| HRSN | Health-Related Social Needs |

| NASEM | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| RCMI | Research Centers in Minority Institutions |

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Rethinking Race and Ethnicity in Biomedical Research; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofili, E.O.; Sarpong, D.; Yanagihara, R.; Tchounwou, P.B.; Fernández-Repollet, E.; Malouhi, M.; Idris, M.Y.; Lawson, K.; Spring, N.H.; Rivers, B.M. The Research Centers in Minority Institutions (RCMI) Consortium: A blueprint for inclusive excellence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powe, N.R.; Yearby, R.; Wilson, M.R. Race and ethnicity in biomedical research: Changing course and improving accountability. JAMA 2025, 333, 935–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Veist, T.A. Why we should continue to study race…but do a better job: An essay on race, racism and health. Ethn. Dis. 1996, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohottige, D.; Boulware, L.E.; Ford, C.L.; Jones, C.; Norris, K.C. Use of race in kidney research and medicine: Concepts, principles, and practice. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.D.; van Stee, E.G.; Regla-Vargas, A. Conceptualizations of race: Essentialism and constructivism. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2023, 49, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, K.; Harris, C.E. Use of Race and Ethnicity in Medicine. In UpToDate; Elmore, J.G., Section Ed.; Givens, J., Hoppin, A.G., Deputy Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Hong Kong, China, 2023. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/use-of-race-and-ethnicity-in-medicine (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Rothstein, R. Suppressed history: The intentional segregation of America’s cities. Am. Educ. 2021, 45, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, R.D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baicker, K.; Chandra, A.; Skinner, J. Geographic variation in health care and the problem of measuring racial disparities. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2005, 48, S42–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P.G. A Social-Psychological Analysis of Vandalism: Making Sense of Senseless Violence: National Technical Information Service; National Technical Information Service: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1972.

- Cohen, D.; Spear, S.; Scribner, R.; Kissinger, P.; Mason, K.; Wildgen, J. “Broken windows” and the risk of gonorrhea. Am. J. Pub. Health 2000, 90, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churruca, K.; Ellis, L.A.; Braithwaite, J. ‘Broken hospital windows’: Debating the theory of spreading disorder and its application to healthcare organizations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harawa, N.T.; Ford, C.L. The foundation of modern racial categories and implications for research on black/white disparities in health. Ethn. Dis. 2009, 19, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Lavizzo-Mourey, R.; Warren, R.C. The concept of race and health status in America. Public Health Rep. 1994, 109, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J. When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.C.F.; Molina, S.J.; Appelbaum, P.S.; Dauda, B.; Di Rienzo, A.; Fuentes, A.; Fullerton, S.M.; Garrison, N.A.; Ghosh, N.; Hammonds, E.M.; et al. Getting genetic ancestry right for science and society. Science 2022, 376, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Crenshaw, K.W.; McCall, L. Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs 2013, 38, 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon (1960) 2002, 50, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P. Invited commentary: “race,” racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 154, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

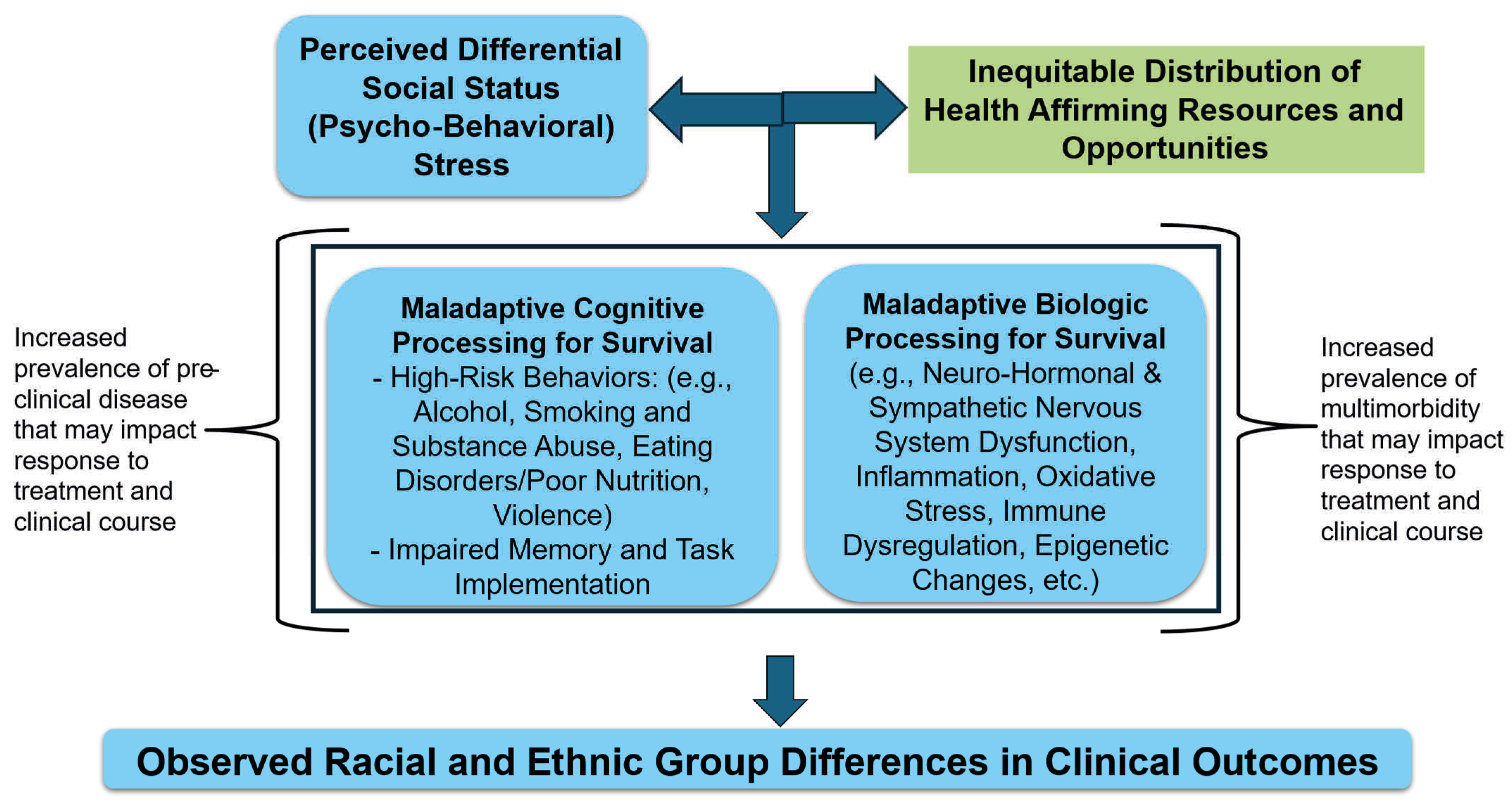

- Thorpe, R.J.; Bruce, M.A., Jr.; Wilder, T.; Jones, H.P.; Thomas-Tobin, C.; Norris, K.C. Health disparities at the intersection of racism, social determinants of health, and downstream biological pathways. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeña, J.P.; Grubbs, V.; Non, A.L. Racialising genetic risk: Assumptions, realities, and recommendations. Lancet 2022, 400, 2147–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Unequal Treatment Revisited: The Current State of Racial Ethnic Disparities in Health Care: Proceedings of a Workshop; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Minority Health and Health Disparities Strategic Plan 2021–2025: Taking the Next Steps; National Institutes of Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Kupersmith, J.; LaBarca, D. Using comparative effectiveness research to remedy health disparities. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2014, 3, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhoff, A.D.; Farrand, E.; Marquez, C.; Cattamanchi, A.; Handley, M.A. Addressing health disparities through implementation science—A need to integrate an equity lens from the outset. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, J.; Bian, J.; Becich, M.J. Advancing social determinants of health research and practice: Data, tools, and implementation. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2025, 9, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; Baciu, A., Negussie, Y., Geller, A., Weinstein, J.N., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Castrucci, B.C.; Auerbach, J. Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. Health Affairs Blog, 16 January 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Fed. Regist. 2024, 89, 22182–22196. [Google Scholar]

- Fruin, K.M.; Tung, E.L.; Franczyk, J.M.; Detmer, W.M. An urban farm–anchored produce prescription program—Food as medicine and economic justice. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 678–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minar, D.W.; Greer, S.A. (Eds.) The Concept of Community: Readings with Interpretations; Routledge Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna, K.L.; Hudson, M.F.; Myers, A.; Kadakia, A.; Rivera, J.; Nutz, T. How can we achieve health equity? Revisit the premise informing the scientific method. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, J.; Avadhanula, L.; Sood, S. A review of strategies and levels of community engagement in strengths-based and needs-based health communication interventions. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1231827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, R.J.; Bruce, M.A.; Beech, B.M.; Heitman, E.; Norris, K.C. Chapter 9. Training the Next Generation of Researchers to Build and Maintain Diverse Cohorts of Clinical Trial Participants. In Race and Research: Perspectives on Minority Participation in Health Studies, 2nd ed.; Beech, B.M., Heitman, E., Eds.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, J.O.; Braun-Inglis, C.; Guidice, S.; Wells, M.; Moorthi, K.; Berenberg, J.; Germain, D.S.; Mohile, S.; Hudson, M.F. Enrolling older adults onto national Cancer Institute-funded clinical trials in community oncology clinics: Barriers and solutions. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2022, 2022, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberth, J.M.; Hung, P.; Benavidez, G.A.; Probst, J.C.; Zahnd, W.E.; McNatt, M.-K.; Toussaint, E.; Merrell, M.A.; Crouch, E.; Oyesode, O.J.; et al. The problem of the color line: Spatial access to hospital services for minoritized racial and ethnic groups. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Norris, K.C.; Hudson, M.F.; Wilson, M.R.; Wojcik, G.L.; Ofili, E.O.; Hedges, J.R. Applying Race and Ethnicity in Health Disparities Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101561

Norris KC, Hudson MF, Wilson MR, Wojcik GL, Ofili EO, Hedges JR. Applying Race and Ethnicity in Health Disparities Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101561

Chicago/Turabian StyleNorris, Keith C., Matthew F. Hudson, M. Roy Wilson, Genevieve L. Wojcik, Elizabeth O. Ofili, and Jerris R. Hedges. 2025. "Applying Race and Ethnicity in Health Disparities Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101561

APA StyleNorris, K. C., Hudson, M. F., Wilson, M. R., Wojcik, G. L., Ofili, E. O., & Hedges, J. R. (2025). Applying Race and Ethnicity in Health Disparities Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101561