Alternative Approaches to Characterizing Disparate Care by Race, Ethnicity, and Insurance Between Hospitals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Measures

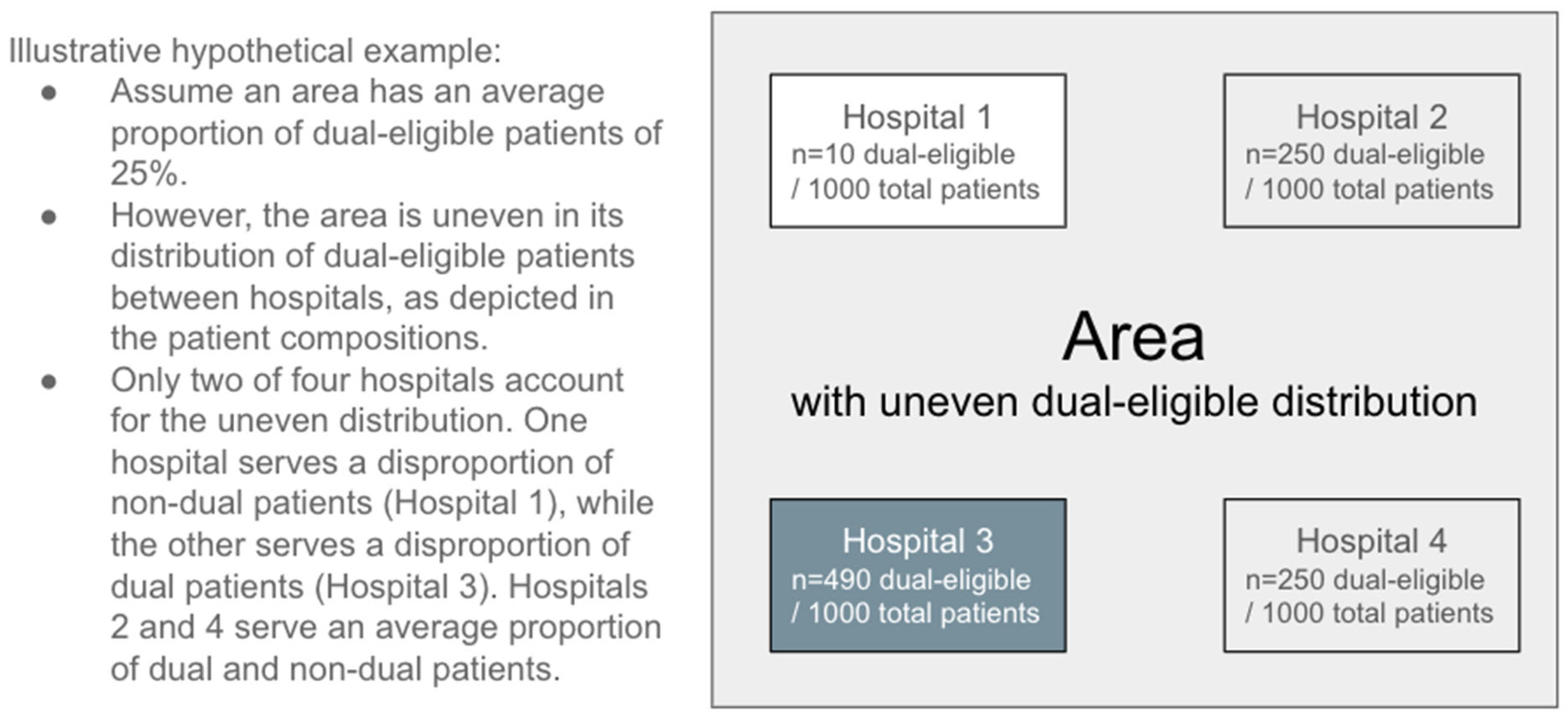

2.2.1. Areas with Uneven Racial/Ethnic and Insurance Patient Compositions—Dissimilarity Index

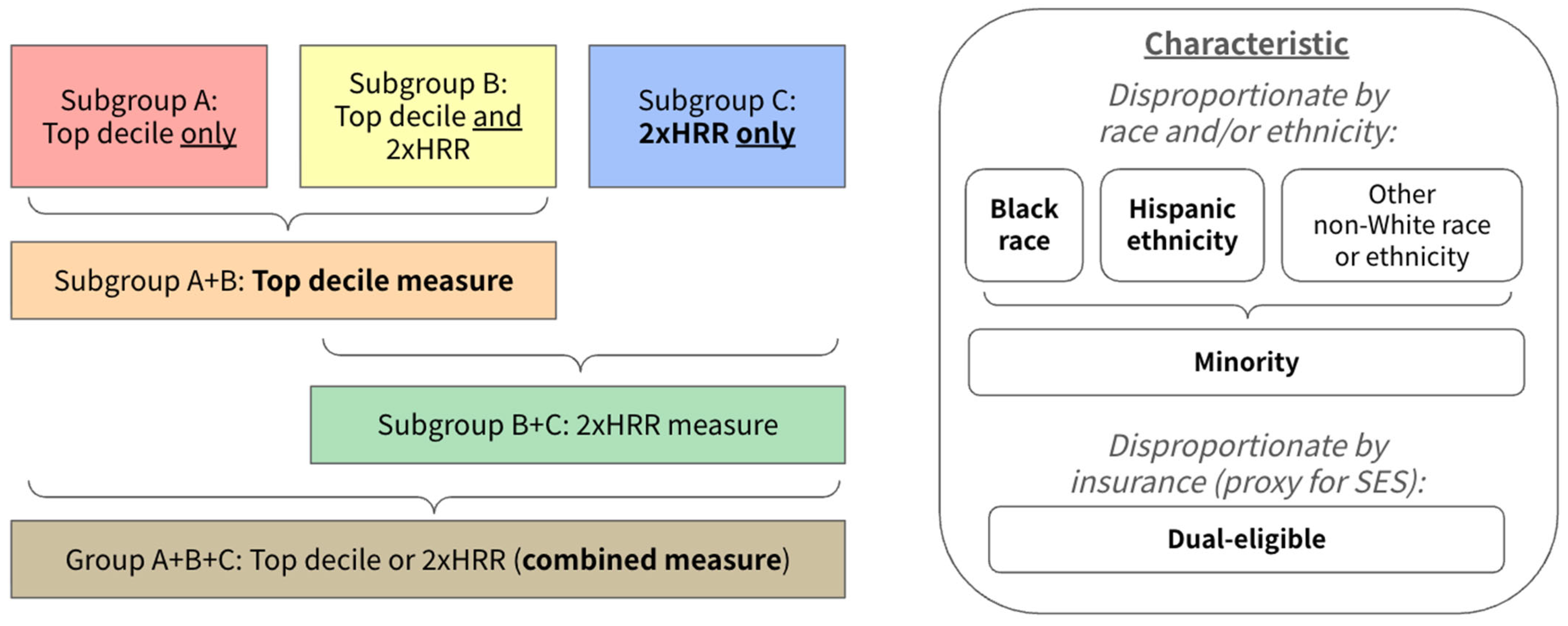

2.2.2. Hospital Disproportion—Top Decile and 2×HRR

2.2.3. Hospital Quality

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Number and Proportion of Hospitals Disproportionately Serving Certain Populations Varies Greatly Based on Measure

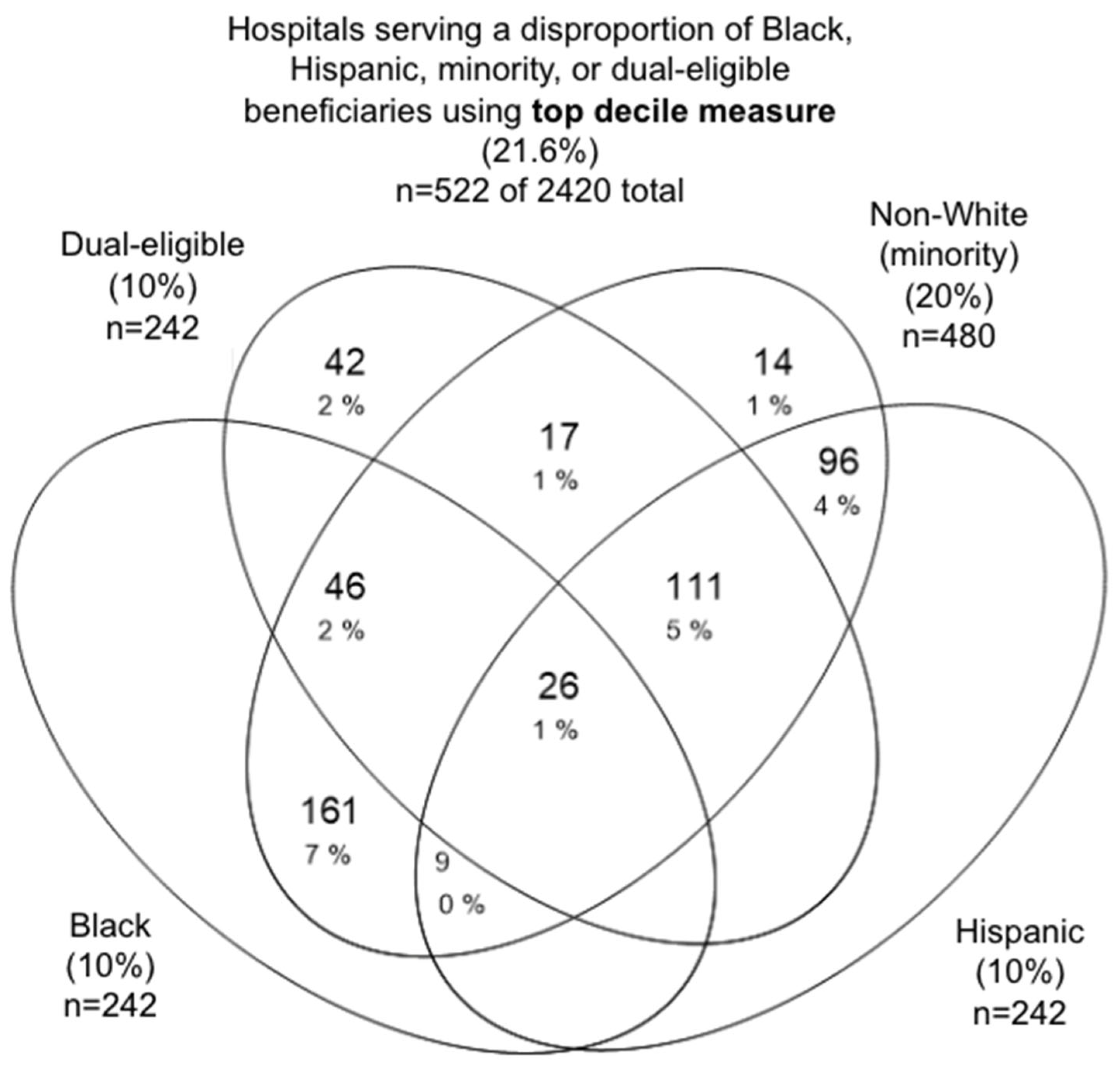

3.1.1. Top Decile Measure

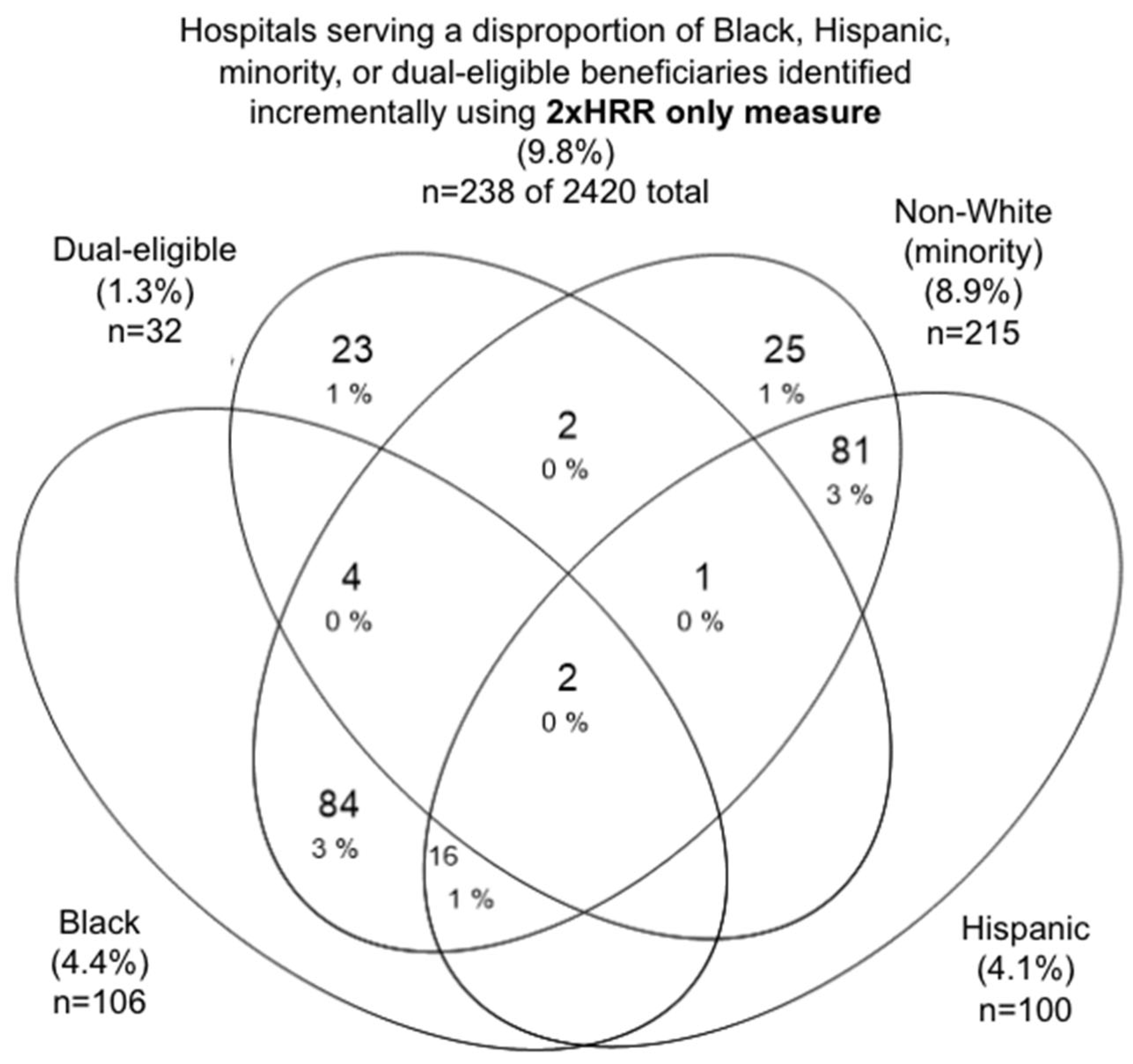

3.1.2. 2×HRR Only Measure

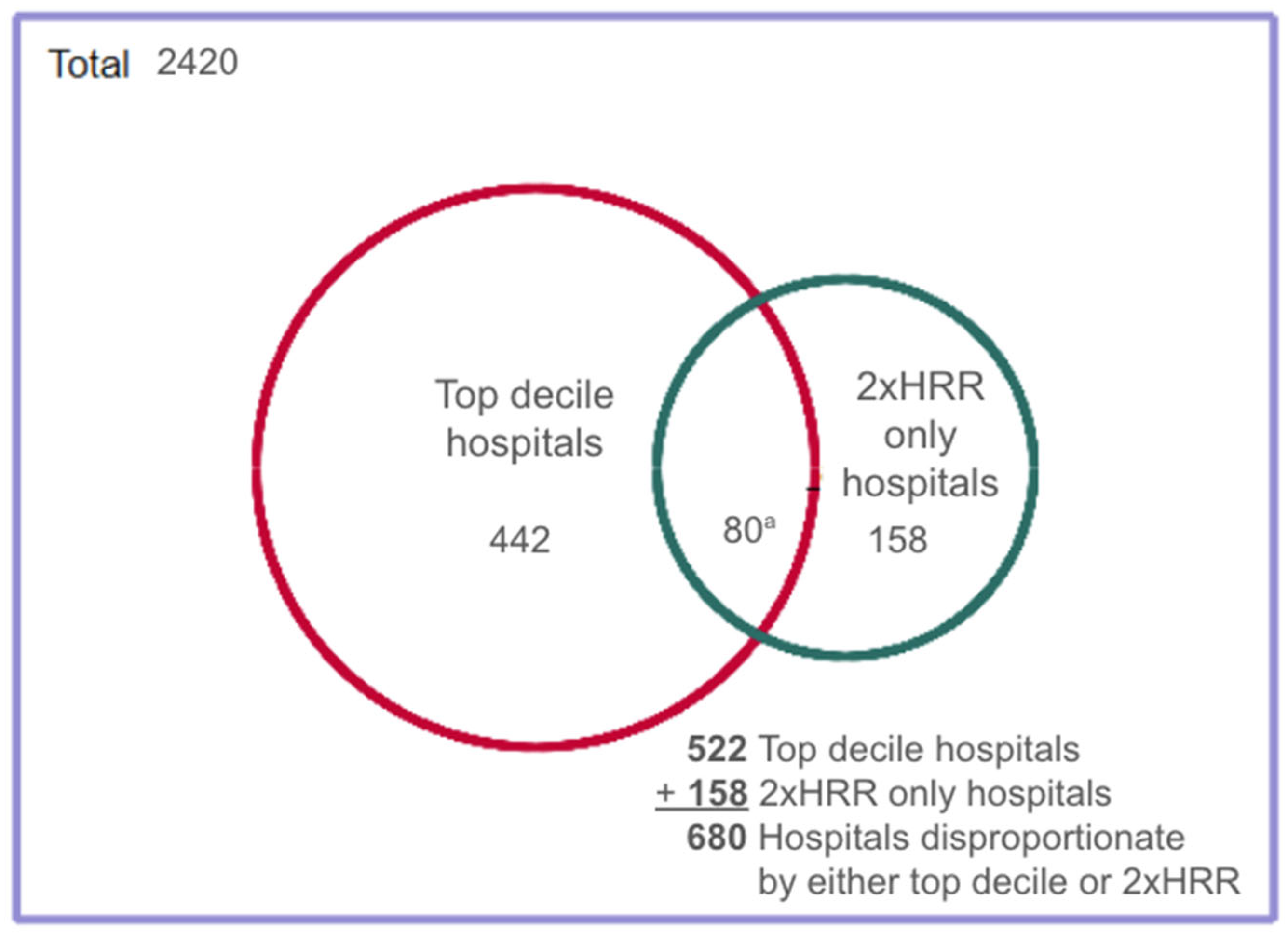

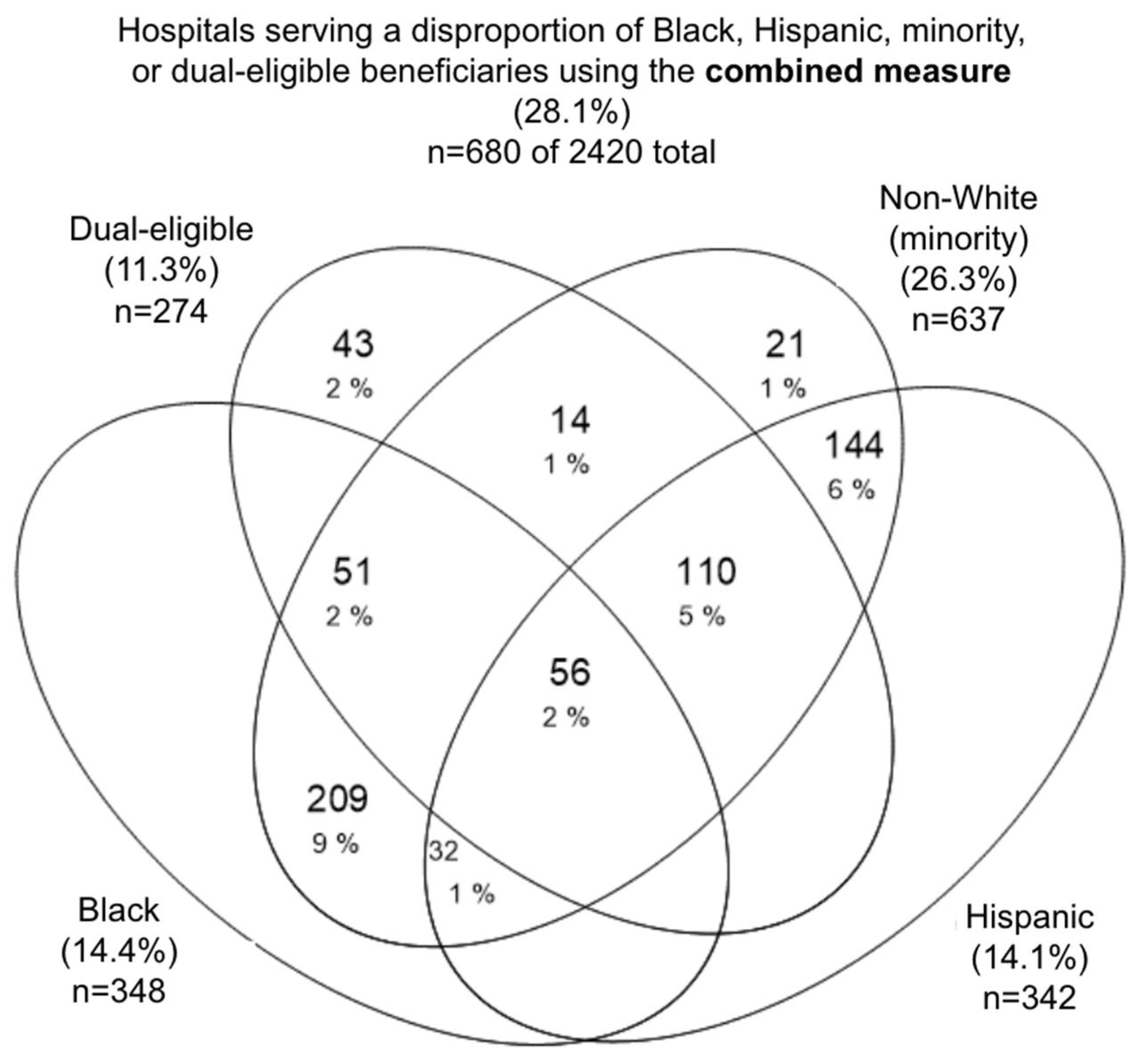

3.1.3. Combined Measure

3.2. Hospital and Area Characteristics Vary Significantly Between Top Decile and 2×HRR Only Groups

3.3. Hospital and Area Characteristics Vary Significantly Between Disproportionate and Non-Disproportionate Hospitals

3.4. Both the Top Decile and the Combined Measure Detected Significant Quality Differences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMC | Boston Medical Center |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CMS | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

| DI | Dissimilarity Index |

| FFS | Fee-for-service |

| HRR | Hospital referral region |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| RUCA | Rural–urban commuting area |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

Appendix A

| Measure of Disproportion | Black | Hispanic | Non-White (Minority) | Dual | Black, Hispanic, Minority, or Dual-Eligible a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Threshold of Black Discharges (±SD) | Black-Serving Hospitals: Number (%) | Mean Threshold of Hispanic Discharges (±SD) | Hispanic-Serving Hospitals: Number (%) | Mean Threshold of Non-White Discharges (±SD) | Minority-Serving Hospitals: Number (%) | Mean Threshold of Dual Discharges (±SD) | Dual-Serving Hospitals: Number (%) | Hospitals: Number (%) | |

| 1.5×HRR average | 21.93% (±20%) | 420 (17.4%) | 14.91% (±19%) | 366 (15.1%) | 33.73% (±25%) | 718 (29.7%) | 47.30% (±20%) | 305 (12.6%) | 794 (32.8%) |

| 2×HRR average | 27.62% (±23%) | 202 (8.4%) | 18.36% (±22%) | 159 (6.6%) | 39.83% (±28%) | 334 (13.8%) | 52.82% (±16%) | 78 (3.2%) | 356 (14.7%) |

| 2.5×HRR average | 35.09% (±25%) | 104 (4.3%) | 21.88% (±24%) | 75 (3.1%) | 46.54% (±28%) | 167 (6.9%) | 62.35% (±15%) | 21 (0.9%) | 171 (7.1%) |

| t-Tests | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disproportionate Hospitals | Non-Disproportionate Hospitals | p-Value | Difference in Means | SMD | |

| Black | 2.75 (n = 420) | 3.18 (n = 2000) | <0.001 | 0.43 | 0.37 |

| Hispanic | 2.75 (n = 366) | 3.17 (n = 2054) | <0.001 | 0.42 | 0.36 |

| Minority | 2.78 (n = 718) | 3.24 (n = 1702) | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.39 |

| Dual-eligible | 2.39 (n = 305) | 3.21 (n = 2115) | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.71 |

| HRR # | HRR City | Hospital Identifier (CCN) | Hospital Name | Hospital City | State | Hospital Percentage API | HRR Percentage API | Hospital Percentage AI/AN | HRR Percentage AI/AN | Hospital Percentage Minority | HRR Percentage Minority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Anchorage | 20026 | Alaska Native Medical Center | Anchorage | AK | 0.36 | 4.46 | 78.82 | 16.68 | 90.76 | 31.23 |

| 12 | Phoenix | 30023 | Flagstaff Medical Center | Flagstaff | AZ | 0.53 | 1.21 | 28.50 | 4.64 | 38.17 | 18.77 |

| 23 | Orange County | 50230 | Garden Grove Hospital & Medical Center | Garden Grove | CA | 67.42 | 20.80 | 0.60 | 0.27 | 82.82 | 36.64 |

| 23 | Orange County | 50570 | UCI Health Fountain Valley | Fountain Valley | CA | 56.49 | 20.80 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 73.50 | 36.64 |

| 23 | Orange County | 50678 | Memorial Care Orange Coast Medical Center | Fountain Valley | CA | 49.54 | 20.80 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 60.59 | 36.64 |

| 56 | Los Angeles | 50737 | Garfield Medical Center | Monterey Park | CA | 73.73 | 12.41 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 92.76 | 48.34 |

| 56 | Los Angeles | 50132 | San Gabriel Valley Medical Center | San Gabriel | CA | 62.26 | 12.41 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 84.57 | 48.34 |

| 56 | Los Angeles | 50353 | Providence Little Company of Mary Med Ctr Torrance | Torrance | CA | 13.97 | 12.41 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 50.21 | 48.34 |

| 65 | Alameda County | 50195 | Washington Hospital | Fremont | CA | 32.18 | 19.02 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 57.59 | 51.70 |

| 65 | Alameda County | 50211 | Alameda Hospital | Alameda | CA | 18.29 | 19.02 | 0.71 | 0.32 | 55.57 | 51.70 |

| 65 | Alameda County | 50488 | Eden Medical Center | Castro Valley | CA | 17.52 | 19.02 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 49.82 | 51.70 |

| 81 | San Francisco | 50407 | Chinese Hospital | San Francisco | CA | 95.51 | 17.18 | 1.60 | 0.44 | 98.40 | 40.15 |

| 81 | San Francisco | 50076 | Kaiser Foundation Hospital—San Francisco | San Francisco | CA | 25.06 | 17.18 | 1.28 | 0.44 | 61.89 | 40.15 |

| 81 | San Francisco | 50055 | California Pacific Medical Center—Mission Bernal | San Francisco | CA | 19.57 | 17.18 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 51.66 | 40.15 |

| 85 | San Mateo County | 50289 | AHMC Seton Medical Center | Daly City | CA | 32.02 | 15.57 | 0.79 | 0.25 | 62.30 | 34.70 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120007 | Kuakini Medical Center | Honolulu | HI | 69.57 | 46.35 | 0.70 | 0.39 | 88.08 | 57.67 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120026 | Pali Momi Medical Center | Aiea | HI | 60.49 | 46.35 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 84.39 | 57.67 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120001 | The Queens Medical Center | Honolulu | HI | 50.30 | 46.35 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 71.77 | 57.67 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120011 | Kaiser Foundation Hospital | Honolulu | HI | 42.27 | 46.35 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 70.06 | 57.67 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120022 | Straub Clinic And Hospital | Honolulu | HI | 47.83 | 46.35 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 66.25 | 57.67 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120006 | Adventist Health Castle | Kailua | HI | 43.39 | 46.35 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 64.74 | 57.67 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120005 | Hilo Medical Center | Hilo | HI | 39.89 | 46.35 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 57.70 | 57.67 |

| 150 | Honolulu | 120014 | Wilcox Memorial Hospital | Lihue | HI | 32.87 | 46.35 | 0.78 | 0.39 | 49.77 | 57.67 |

| 227 | Boston | 220116 | Tufts Medical Center | Boston | MA | 5.80 | 1.60 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 21.77 | 10.41 |

| 250 | Duluth | 240019 | Essentia Health Duluth | Duluth | MN | 0.83 | 0.25 | 4.67 | 1.65 | 12.00 | 5.30 |

| 267 | Joplin | 370113 | Integris Grove Hospital | Grove | MO | 1.38 | 0.54 | 13.77 | 2.97 | 15.70 | 7.41 |

| 281 | Lebanon | 300003 | Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital | Lebanon | NH | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 5.70 | 2.81 |

| 293 | Albuquerque | 320061 | Gallup Indian Medical Center | Gallup | NM | 1.34 | 0.86 | 93.30 | 16.41 | 98.66 | 43.22 |

| 301 | East Long Island | 330055 | New York-Presbyterian/Queens | Flushing | NY | 18.57 | 4.31 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 49.26 | 22.20 |

| 322 | Fargo/Moorhead, MN | 240100 | Sanford Bemidji Medical Center | Bemidji | ND | 0.48 | 0.43 | 16.78 | 4.48 | 20.44 | 9.02 |

| 323 | Grand Forks | 350019 | Altru Hospital | Grand Forks | ND | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 9.96 | 4.96 |

| 329 | Columbus | 360085 | Ohio State University Hospitals | Columbus | OH | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 18.70 | 9.26 |

| 339 | Oklahoma City | 370180 | Chickasaw Nation Medical Center | Ada | OK | 1.67 | 0.89 | 79.33 | 4.96 | 83.67 | 15.19 |

| 340 | Tulsa | 370171 | W W Hastings Indian Hospital | Tahlequah | OK | 0.95 | 0.74 | 81.82 | 10.55 | 86.74 | 19.21 |

| 457 | Casper | 530008 | Sagewest Health Care | Riverton | WY | 1.02 | 0.34 | 20.08 | 3.55 | 23.98 | 10.13 |

| Top Decile or 2×HRR (Group A + B + C) | SMD (95% CI) | Top Decile (Subgroup A + B) | SMD (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 348 (14.4%) | −0.50 (0.37–0.60) | 242 (10.0%) | −0.65 (0.50–0.76) |

| Hispanic | 342 (14.1%) | −0.51 (0.39–0.62) | 242 (10.0%) | −0.57 (0.43–0.70) |

| Minority | 637 (26.3%) | −0.52 (0.42–0.61) | 480 (19.8%) a | −0.59 (0.48–0.69) |

| Dual-eligible | 274 (11.3%) | −0.79 (0.65–0.90) | 242 (10.0%) | −0.80 (0.65–0.92) |

| Black, Hispanic, minority, or dual-eligible | 680 (28.1%) | −0.54 (0.45–0.63) | 522 (21.6%) | −0.62 (0.52–0.71) |

| Top Decile | Both Top Decile and 2×HRR | 2×HRR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disproportionate Hospital | Non-Disproportionate Hospital | SMD | Disproportionate Hospital | Non-Disproportionate Hospital | SMD | Disproportionate Hospital | Non-Disproportionate Hospital | SMD | |

| Black | 2.46 | 3.18 | 0.64 | 2.62 | 3.19 | 0.50 | 2.64 | 3.15 | 0.44 |

| Hispanic | 2.52 | 3.17 | 0.57 | 2.61 | 3.19 | 0.51 | 2.66 | 3.14 | 0.43 |

| Minority | 2.57 | 3.24 | 0.59 | 2.67 | 3.26 | 0.52 | 2.70 | 3.17 | 0.42 |

| Dual | 2.30 | 3.19 | 0.80 | 2.33 | 3.20 | 0.79 | 2.32 | 3.13 | 0.74 |

References

- Sanford, S.T. Conditions of Participation: Incorporating the History of Hospital Desegregation. J. Law. Med. Ethics 2023, 51, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largent, E.A. Public Health, Racism, and the Lasting Impact of Hospital Segregation. Public Health Rep. 2018, 133, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.P. The federal government’s use of Title VI and Medicare to racially integrate hospitals in the United States, 1963 through 1967. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1850–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, V.; Berney, B. Creating Equal Health Opportunity: How the Medical Civil Rights Movement and the Johnson Administration Desegregated U.S. Hospitals. J. Am. Hist. 2019, 105, 885–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S. Dr. Philip Lee Is Dead at 96; Engineered Introduction of Medicare. New York Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/03/us/dr-philip-lee-dead.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Kung, A.; Liu, B.; Holaday, L.W.; McKendrick, K.; Chen, Y.; Siu, A.L. Segregation in hospital care for Medicare beneficiaries by race and ethnicity and dual-eligible status from 2013 to 2021. Health Serv. Res. 2025, 60, e14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.C.; Hammond, G.; Esposito, M.; Majewski, C.; Foraker, R.E.; Joynt Maddox, K.E. Segregated Patterns of Hospital Care Delivery and Health Outcomes. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e234172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, S.F.; O’Sullivan, D. 3. Measures of Spatial Segregation. Sociol. Methodol. 2004, 34, 121–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P. Confronting Institutionalized Racism. Phylon 1960- 2002, 50, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Hogue, C.R. Is Segregation Bad for Your Health? Epidemiol. Rev. 2009, 31, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Park, K.; Matthews, S.A. Racial/ethnic segregation and health disparities: Future directions and opportunities. Sociol. Compass 2020, 14, e12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelstein, G.; Ceasar, J.N.; Himmelstein, K.E. Hospitals That Serve Many Black Patients Have Lower Revenues and Profits: Structural Racism in Hospital Financing. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmelstein, G.; Himmelstein, K.E.W. Inequality Set in Concrete: Physical Resources Available for Care at Hospitals Serving People of Color and Other U.S. Hospitals. Int. J. Health Serv. Plan. Adm. Eval. 2020, 50, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egede, L.E.; Walker, R.J.; Campbell, J.A.; Linde, S.; Hawks, L.C.; Burgess, K.M. Modern Day Consequences of Historic Redlining: Finding a Path Forward. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 1534–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, E.E.; Malcoe, L.H.; Laurent, S.E.; Richardson, J.; Mitchell, B.C.; Meier, H.C.S. The legacy of structural racism: Associations between historic redlining, current mortgage lending, and health. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelke, C.; Outrich, M.; Baek, M.; Reece, J.; Osypuk, T.L.; McArdle, N.; Ressler, R.W.; Acevedo-Garcia, D. Connecting past to present: Examining different approaches to linking historical redlining to present day health inequities. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Blustein, J.; Weitzman, B.C. Race, Segregation, and Physicians’ Participation in Medicaid. Milbank Q. 2006, 84, 239–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.Y.; Tseng, M. Ethnic density and cancer: A review of the evidence. Cancer 2018, 124, 1877–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuemmeler, B.F.; Shen, J.; Zhao, H.; Winn, R. Neighborhood deprivation, racial segregation and associations with cancer risk and outcomes across the cancer-control continuum. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperino, J. Safety-net Hospitals in Brooklyn, New York: A Review. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2023, 34, 1452–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, L.S.; Staiger, D.; Horbar, J.D.; Carpenter, J.; Kenny, M.; Geppert, J.; Rogowski, J. Mortality Among Very Low-Birthweight Infants in Hospitals Serving Minority Populations. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.C.; Shaw, J.D.; Ma, Y.; Rhoads, K.F. The role of the hospital and health care system characteristics in readmissions after major surgery in California. Surgery 2016, 159, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Zheng, C.; Lawrence, S.; Hong, Y.; Shara, N.M.; Johnson, L.B.; Al-Refaie, W.B. Do hospital factors impact readmissions and mortality after colorectal resections at minority-serving hospitals? Surgery 2017, 161, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faigle, R.; Cooper, L.A.; Gottesman, R.F. Race Differences in Gastrostomy Tube Placement After Stroke in Majority-White, Minority-Serving, and Racially Integrated US Hospitals. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faigle, R.; Cooper, L.A.; Gottesman, R.F. Lower carotid revascularization rates after stroke in racial/ethnic minority-serving US hospitals. Neurology 2019, 92, e2653–e2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.P.; Nguyen, D.-D.; Meirkhanov, A.; Golshan, M.; Melnitchouk, N.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Kilbridge, K.L.; Kibel, A.S.; Cooper, Z.; Weissman, J.; et al. Association of Care at Minority-Serving vs Non-Minority-Serving Hospitals With Use of Palliative Care Among Racial/Ethnic Minorities With Metastatic Cancer in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e187633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, B.; Danziger, J.; Walley, K.R.; Kumar, A.; Celi, L.A. Treatment in Disproportionately Minority Hospitals Is Associated With Increased Risk of Mortality in Sepsis: A National Analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, D.P.; Lopez, L.; Isaac, T.; Jha, A.K. How Do Black-Serving Hospitals Perform on Patient Safety Indicators?: Implications for National Public Reporting and Pay-for-Performance. Med. Care 2010, 48, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, J.L.; Hogan, T.H.; Opoku-Agyeman, W.; Menachemi, N. Defining safety net hospitals in the health services research literature: A systematic review and critical appraisal. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, W.R.; Hansmann, K.J.; Carlson, A.; Kind, A.J.H. Evaluating How Safety-Net Hospitals Are Identified: Systematic Review and Recommendations. Health Equity 2022, 6, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, I.; Fingar, K.R.; Cutler, E.; Guo, J.; Jiang, H.J. Comparison of 3 Safety-Net Hospital Definitions and Association With Hospital Characteristics. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, M.; Mohamed, M.; Burns, A.; Biniek, J.F.; Ochieng, N.; Chidambaram, P. A Profile of Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees (Dual Eligibles). Kaiser Family Foundation > Medicare. 31 January 2023. Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/a-profile-of-medicare-medicaid-enrollees-dual-eligibles/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Zhilkova, A.; Alsabahi, L.; Olson, D.; Maru, D.; Tsao, T.-Y.; Morse, M.E. Hospital segregation, critical care strain, and inpatient mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan Sarrazin, M.S.; Campbell, M.E.; Richardson, K.K.; Rosenthal, G.E. Racial Segregation and Disparities in Health Care Delivery: Conceptual Model and Empirical Assessment. Health Serv. Res. 2009, 44, 1424–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, R.M.; Davidson, P.L. Improving Access to Care in America: Individual and Contextual Indicators. In Changing the U.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services, Policy, and Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Is Racism a Fundamental Cause of Inequalities in Health? Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.A.; Arkin, E.; Proctor, D.; Kauh, T.; Holm, N. Systemic And Structural Racism: Definitions, Examples, Health Damages, And Approaches To Dismantling: Study examines definitions, examples, health damages, and dismantling systemic and structural racism. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, N.; Kim, R.; Feldman, J.; Waterman, P.D. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 788–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N.; Waterman, P.D.; Spasojevic, J.; Li, W.; Maduro, G.; Van Wye, G. Public Health Monitoring of Privilege and Deprivation With the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Soc. Forces 1988, 67, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Borrell, L.N. Racial/ethnic residential segregation: Framing the context of health risk and health disparities. Health Place 2011, 17, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Haas, J.S.; Williams, D.R. Elucidating the Role of Place in Health Care Disparities: The Example of Racial/Ethnic Residential Segregation. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 47 Pt 2, 1278–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, S.F.; Firebaugh, G. 2. Measures of Multigroup Segregation. Sociol. Methodol. 2002, 32, 33–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, O.D.; Duncan, B. A Methodological Analysis of Segregation Indexes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1955, 20, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, A.; Holaday, L.W.; Liu, B.; Li, L.; Siu, A. How Is Racial/Ethnic Segregation between Hospitals Best Characterized? Academy Health 2024 Annual Research Meeting. 1 July 2024. Available online: https://academyhealth.confex.com/academyhealth/2024arm/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/63177 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Joynt, K.E. Thirty-Day Readmission Rates for Medicare Beneficiaries by Race and Site of Care. JAMA 2011, 305, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krimphove, M.J.; Fletcher, S.A.; Cole, A.P.; Berg, S.; Sun, M.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Mahal, B.A.; Nguyen, P.L.; Choueiri, T.K.; Kibel, A.S.; et al. Quality of Care in the Treatment of Localized Intermediate and High Risk Prostate Cancer at Minority Serving Hospitals. J. Urol. 2019, 201, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshami, M.; Bailey, L.; Hoehn, R.S.; Ammori, J.B.; Hardacre, J.M.; Selfridge, J.E.; Bajor, D.; Mohamed, A.; Chakrabarti, S.; Mahipal, A.; et al. Differences in the surgical management of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma at minority versus non-minority-serving hospitals. Surgery 2023, 174, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Kantor, O.; Mittendorf, E.A.; King, T.A.; Minami, C.A. Race and Site of Care Impact Treatment Delays in Older Women with Non-Metastatic Breast Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4103–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (with CD); National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; p. 12875. ISBN 978-0-309-21582-4.

- Board on Health Care Services; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Unequal Treatment Revisited: The Current State of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care: Proceedings of a Workshop; Amankwah, F.K., Alper, J., Nass, S.J., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; p. 27448. ISBN 978-0-309-71474-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, E.J.; Fleischut, P.; Regan, B.K. Quality Measurement in Healthcare. Annu. Rev. Med. 2013, 64, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.L.; Howell, E.A.; Wong, E.S.; Hernandez, S.E.; Rinne, S.T.; Sulc, C.A.; Neely, E.L.; Liu, C. Methods for Measuring Racial Differences in Hospitals Outcomes Attributable to Disparities in Use of High-Quality Hospital Care. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 52, 826–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binger, T.; Chen, H.; Harder, B. Hospital Rankings and Health Equity. JAMA 2022, 328, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olecki, E.J.; Perez Holguin, R.A.; Mayhew, M.M.; Wong, W.G.; Vining, C.C.; Peng, J.S.; Shen, C.; Dixon, M.E.B. Disparities in Surgical Treatment of Resectable Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma at Minority Serving Hospitals. J. Surg. Res. 2024, 294, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Inpatient Hospitals—By Provider. 2023. Available online: https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-inpatient-hospitals/medicare-inpatient-hospitals-by-provider/data (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Overall Hospital Quality Star Rating. Available online: https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/topics/hospitals/overall-hospital-quality-star-rating/ (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospitals Archived Data Snapshots. 2025. Available online: https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/archived-data/hospitals (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. 8 May 2025. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Dartmouth Atlas Project. Research Methods. 2024. Available online: https://www.dartmouthatlas.org/research-methods/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Supplemental Data—Crosswalks. Available online: https://data.dartmouthatlas.org/supplemental/#crosswalks (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services > Office of Enterprise Data and Analytics. Medicare Fee-For-Service Provider Utilization & Payment Data Inpatient Public Use File: A Methodological Overview. May 2024. Available online: https://data.cms.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/MUP_INP_RY24_20240523_Methodology_508.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Allen, R.; Burgess, S.; Davidson, R.; Windmeijer, F. More reliable inference for the dissimilarity index of segregation: Inference for dissimilarity index. Econom. J. 2015, 18, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabb, L.P.; Bayliss, R.; Xu, Y. Spatial and spatio-temporal statistical implications for measuring structural racism: A review of three widely used residential segregation measures. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2024, 50, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Mean Difference, Standardized Mean Difference (SMD), and Their Use in Meta-Analysis: As Simple as It Gets. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 20f13681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Aloe, A.M. Evaluation of various estimators for standardized mean difference in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS/ACCESS, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2025.

- StataNow/MP, version 18.5; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2025.

- Tsai, T.C.; Orav, E.J.; Joynt, K.E. Disparities in Surgical 30-Day Readmission Rates for Medicare Beneficiaries by Race and Site of Care. Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.F.; Zheng, J.; Orav, E.J.; Epstein, A.M.; Jha, A.K. Medicare Program Associated With Narrowing Hospital Readmission Disparities Between Black And White Patients. Health Aff. Proj. Hope 2018, 37, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, O.D. The measurement of population distribution. Popul. Stud. 1957, 11, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N.; Waterman, P.D.; Gryparis, A.; Coull, B.A. Black carbon exposure, socioeconomic and racial/ethnic spatial polarization, and the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE). Health Place 2015, 34, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrabee Sonderlund, A.; Charifson, M.; Schoenthaler, A.; Carson, T.; Williams, N.J. Racialized economic segregation and health outcomes: A systematic review of studies that use the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for race, income, and their interaction. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, E. The Divergence Index: A Decomposable Measure of Segregation and Inequality. arXiv 2024, arXiv:1508.01167. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.01167 (accessed on 30 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- UC Berkeley Othering & Belonging Institute. The Roots of Structural Racism Project > Technical Appendix. Available online: https://belonging.berkeley.edu/technical-appendix (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Menendian, S.; Gambhir, S.; Gailes, A. The Roots of Structural Racism Project: Twenty-First Century Racial Residential Segregation in the United States; University of California Berkeley, Othering and Belonging Institute: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–43. Available online: https://belonging.berkeley.edu/roots-structural-racism (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Diaz, A.; Dalmacy, D.; Herbert, C.; Mirdad, R.S.; Hyer, J.M.; Pawlik, T.M. Association of County-Level Racial Diversity and Likelihood of a Textbook Outcome Following Pancreas Surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 8076–8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akré, E.-R.L.; Chyn, D.; Carlos, H.A.; Barnato, A.E.; Skinner, J. Measuring Local-Area Racial Segregation for Medicare Hospital Admissions. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e247473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B. The racial segregation of hospital care revisited: Medicare discharge patterns and their implications. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 88, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, C.E.; Partain, A.T.; Crowe, R.P.; Brown, L.H. Ambulance Transport Destinations In The US Differ By Patient Race And Ethnicity: Study examines ambulance transport destinations by patient race and ethnicity. Health Aff. 2023, 42, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsuan, C.; Carr, B.G.; Vanness, D.; Wang, Y.; Leslie, D.L.; Dunham, E.; Rogowski, J.A. A Conceptual Framework for Optimizing the Equity of Hospital-Based Emergency Care: The Structure of Hospital Transfer Networks. Milbank Q. 2023, 101, 74–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsuan, C.; Vanness, D.J.; Zebrowski, A.; Carr, B.G.; Norton, E.C.; Buckler, D.G.; Wang, Y.; Leslie, D.L.; Dunham, E.F.; Rogowski, J.A. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department transfers to public hospitals. Health Serv. Res. 2024, 59, e14276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, P.D.; Stone, D.J.; Geisler, B.P.; McLennan, S.; Celi, L.A.; Rush, B. Racial and Geographic Disparities in Interhospital ICU Transfers. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, e76–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasser, K.E.; Hanchate, A.D.; McCormick, D.; Chu, C.; Xuan, Z.; Kressin, N.R. Massachusetts Health Reform’s Effect on Hospitals’ Racial Mix of Patients and on Patients’ Use of Safety-net Hospitals. Med. Care 2016, 54, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, I.G. Is Segregation Bad for Your Health? The Case of Low Birth Weight. Brook.-Whart. Pap. Urban Aff. 2000, 2000, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.S.; Kennelly, J.F.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Oh, H.-J.; Kaplan, G.; Lynch, J. Relationship between Premature Mortality and Socioeconomic Factors in Black and White Populations of US Metropolitan Areas. Public Health Rep. 2001, 116, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, M.; Biniek, J.F.; Damico, A.; Neuman, T. Medicare Advantage in 2024: Enrollment Update and Key Trends. Kaiser Family Foundation > Medicare. 8 August 2024. Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2024-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Jia, P.; Wang, F.; Xierali, I.M. Evaluating the effectiveness of the Hospital Referral Region (HRR) boundaries: A pilot study in Florida. Ann. GIS 2020, 26, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, M.K.; Miller, A.L.; Bergmark, R.W.; Semco, R.; Zogg, C.K.; Goralnick, E.; Jarman, M.P. The Utility of a Novel Definition of Health Care Regions in the United States in the Era of COVID-19: A Validation of the Pittsburgh Atlas Using Pneumonia Admissions. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2022, 79, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Baik, S.H.; Fendrick, A.M.; Baicker, K. Comparing Local and Regional Variation in Health Care Spending. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1724–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T. Building on the Legacy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare to Advance Health Equity: Q & A with Dr. Amber Barnato. Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine > News. 1 June 2023. Available online: https://geiselmed.dartmouth.edu/news/2023/building-on-the-legacy-of-the-dartmouth-atlas-of-healthcare-to-advance-health-equity-q-a-with-dr-amber-barnato/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Menon, N.M.; Leslie, T.F.; Frankenfeld, C.L. Cancer-related diagnostic and treatment capabilities of hospitals in the context of racial residential segregation. Public Health 2020, 182, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.; Gibson, B.; Matthews, L.; Zhang, S.; Escarce, J.J.; Schuler, M.; Damberg, C.L. The segregation of physician networks providing care to black and white patients with heart disease: Concepts, measures, and empirical evaluation. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 343, 116511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, D.; Maillie, L.; Dhamoon, M. Provider care segregation and hospital-region racial disparities for carotid interventions in the USA. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2023, 16, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Top Decile or 2×HRR (Combined Measure, A + B + C) | Top Decile Only (Subgroup A) | Both Top Decile and 2×HRR (Subgroup B) | 2×HRR Only (Subgroup C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 348 (14.4%) | 146 (6.0%) | 96 (4.0%) | 106 (4.4%) |

| Hispanic | 342 (14.1%) | 183 (7.6%) | 59 (2.4%) | 100 (4.1%) |

| Minority | 637 (26.3%) | 368 (15.2%) a | 177 (7.3%) a | 215 (8.9%) |

| Dual-eligible | 274 (11.3%) | 196 (8.1%) | 46 (1.9%) | 32 (1.3%) |

| Black, Hispanic, minority, or dual-eligible | 680 (28.1%) | 423 (17.5%) | 168 (6.9%) | 238 (9.8%) |

| Black | Hispanic | Minority | Dual | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Decile (n = 242) | 2×HRR Only (n = 106) | p-Value | Top Decile (n = 242) | 2×HRR Only (n = 100) | p-Value | Top Decile (n = 480) a | 2×HRR Only (n = 157) | p-Value | Top Decile (n = 242) | 2×HRR Only (n = 32) | p-Value | |

| Discharges per year Median (IQR) | 1334 (744–2198) | 937 (510–1889) | 0.001 ** | 1054 (637–1922) | 579 (335–1264) | <0.001 *** | 1212 (680–2120) | 722 (371–1739) | <0.001 *** | 1001 (637–1617) | 588 (410–895) | 0.001 ** |

| Number of hospitals in HRR Median (IQR) | 13.0 (9.0–22.0) | 14.0 (6.0–23.0) | 0.212 | 16.0 (7.0–24.0) | 14.5 (7.0–23.5) | 0.188 | 13.0 (8.0–23.0) | 14.0 (6.0–23.0) | 0.079 | 19.0 (10.0–25.0) | 21.0 (9.0–38.0) | 0.815 |

| Corresponding DI b of HRR Mean (SD) | 0.281 (0.124) | 0.297 (0.084) | 0.246 | 0.228 (0.094) | 0.207 (0.068) | 0.042 * | 0.246 (0.100) | 0.208 (0.087) | <0.001 *** | 0.265 (0.109) | 0.181 (0.055) | <0.001 *** |

| CMS star quality rating Mean (SD) | 2.45 (1.09) | 3.01 (1.05) | <0.001 *** | 2.52 (1.11) | 2.83 (1.02) | 0.016 * | 2.57 (1.11) | 2.94 (1.03) | <0.001 *** | 2.30 (1.09) | 2.53 (1.08) | 0.262 |

| Percent rural (Number rural hospitals/total) | 11.2% (27/242) | 17.0% (18/106) | 0.136 | 4.1% (10/242) | 42.0% (42/100) | <0.001 *** | 8.8% (42/480) | 36.3% (57/157) | <0.001 *** | 8.3% (20/242) | 43.8% (14/32) | <0.001 *** |

| Census region (Column percent) | NE- 37 (15.3%) MW- 43 (17.8%) S- 145 (59.9%) W- 17 (7.0%) | NE- 24 (22.6%) MW- 28 (26.4%) S- 12 (11.3%) W- 42 (39.6%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 21 (8.7%) MW- 9 (3.7%) S- 66 (27.3%) W- 146 (60.3%) | NE- 28 (28.0%) MW- 31 (31.0%) S- 39 (39.0%) W- 2 (2.0%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 48 (10.0%) MW- 47 (9.8%) S- 207 (43.1%) W- 178 (37.1%) | NE- 39 (24.8%) MW- 53 (33.8%) S- 39 (24.8%) W- 26 (16.6%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 51 (21.1%) MW- 28 (11.6%) S- 40 (16.5%) W- 123 (50.8%) | NE- 2 (6.3%) MW- 3 (9.4%) S- 23 (71.9%) W- 4 (12.5%) | <0.01 ~~ |

| Black | Hispanic | Minority | Dual | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black-Serving (n = 242) | Not Black-Serving (n = 2178) | p-Value | Hispanic- Serving (n = 242) | Not Hispanic-Serving (n = 2178) | p-Value | Minority- Serving (n = 480) a | Not Minority-Serving (n = 1940) | p-Value | Dual-Serving (n = 242) | Not Dual-Serving (n = 2178) | p-Value | |

| Discharges per year Median (IQR) | 1334 (744–2198) | 1524 (779–2799) | 0.026 * | 1054 (637–1922) | 1566 (798–2856) | <0.001 *** | 1212 (680–2120) | 1610 (803–2914) | <0.001 *** | 1001 (637–1617) | 1606 (801–2878) | <0.001 *** |

| Number of hospitals in HRR Median (IQR) | 14.0 (9.0–24.0) | 12.0 (6.0–23.0) | <0.001 *** | 18.0 (9.0–26.0) | 12.0 (6.0 = 23.0) | <0.001 *** | 15.0 (9.0–24.0) | 12.0 (6.0–22.0) | <0.001 *** | 20.0 (10.0–28.0) | 12.0 (6.0–22.0) | <0.001 *** |

| Corresponding DI b of HRR Mean (SD) | 0.281 (0.104) | 0.246 (0.240–0.249) | <0.001 *** | 0.228 (0.094) | 0.165 (0.073) | <0.001 *** | 0.246 (0.100) | 0.185 (0.091) | <0.001 *** | 0.265 (0.109) | 0.146 (0.071) | <0.001 *** |

| CMS star quality rating Mean (SD) c | 2.45 (1.09) | 3.18 (1.15) | <0.001 *** | 2.52 (1.15) | 3.17 (1.11) | <0.001 *** | 2.57 (1.11) | 3.24 (1.14) | <0.001 *** | 2.30 (1.09) | 3.19 (1.14) | <0.001 *** |

| Percent rural (Number rural hospitals/total) | 11.2% (27/242) | 23.7% (515/2178) | <0.001 *** | 4.1% (10/242) | 24.4% (532/2178) | <0.001 *** | 8.8% (42/480) | 25.8% (500/1940) | <0.001 *** | 8.3% (20/242) | 24.0% (522/2178) | <0.001 *** |

| Census region (Column percent) | NE- 37 (15.3%) MW- 43 (17.8%) S- 145 (59.9%) W- 17 (7.0%) | NE- 367 (16.9%) MW- 534 (24.5%) S- 800 (36.7%) W-477 (21.9%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 21 (8.7%) MW- 9 (3.7%) S- 66 (27.3%) W- 146 (60.3%) | NE- 383 (17.6%) MW- 568 (26.1%) S- 879 (40.4%) W-348 (16.0%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 48 (10.0%) MW- 47 (9.8%) S- 207 (43.1%) W- 178 (37.1%) | NE- 356 (18.4%) MW- 530 (27.3%) S- 738 (38.0%) W-316 (16.3%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 51 (21.1%) MW- 28 (11.6%) S- 40 (16.5%) W- 123 (50.8%) | NE- 353 (16.2%) MW- 549 (25.2%) S- 905 (41.6%) W-371 (17.0%) | <0.01 ~~ |

| Black | Hispanic | Minority | Dual | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black-Serving (n = 348) | Not Black-Serving (n = 2072) | p-Value | Hispanic- Serving (n = 342) | Not Hispanic-Serving (n = 2078) | p-Value | Minority- Serving (n = 637) a | Not Minority-Serving (n = 1783) | p-Value | Dual-Serving (n = 274) | Not Dual-Serving (n = 2146) | p-Value | |

| Discharges per year Median (IQR) | 1157 (657–2106) | 1573 (796–2861) | <0.001 *** | 888 (514–1682) | 1634 (838–2919) | <0.001 *** | 1083 (589–2061) | 1691 (854–3067) | <0.001 *** | 939 (589–1515) | 1624 (811–2914) | <0.001 *** |

| Number of hospitals in HRR Median (IQR) | 14.0 (8.0–24.0) | 12.0 (6.0–23.0) | 0.004 ** | 18.0 (8.0–26.0) | 12.0 (6.0–22.0) | <0.001 *** | 15.0 (8.0–24.0) | 12.0 (6.0–22.0) | <0.001 *** | 21.0 (10.0–32.0) | 12.0 (6.0–22.0) | <0.001 *** |

| Corresponding DI a of HRR Mean (SD) | 0.286 (0.113) | 0.243 (0.105) | <0.001 *** | 0.222 (0.088) | 0.163 (0.073) | <0.001 *** | 0.232 (0.099) | 0.185 (0.091) | <0.001 *** | 0.255 (0.108) | 0.145 (0.071) | <0.001 *** |

| CMS star quality rating Mean (SD) b | 2.62 (1.10) | 3.19 (1.16) | <0.001 *** | 2.61 (1.09) | 3.19 (1.16) | <0.001 *** | 2.67 (1.10) | 3.26 (1.15) | <0.001 *** | 2.33 (1.09) | 3.20 (1.14) | <0.001 *** |

| Percent rural (Number rural hospitals/total) | 12.9% (45/348) | 24.0% (497/2072) | <0.001 *** | 15.2% (52/342) | 23.6% (490/2078) | <0.001 *** | 15.5% (99/637) | 24.9% (443/1783) | <0.001 *** | 12.4% (34/274) | 23.7% (508/2146) | <0.001 *** |

| Census region (Column percent) | NE- 61 (17.5%) MW- 71 (20.4%) S- 157 (45.1%) W- 59 (17.0%) | NE- 343 (16.6%) MW- 506 (24.4%) S- 788 (38.0%) W- 435 (21.0%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 49 (14.3%) MW- 40 (11.7%) S- 105 (30.7%) W- 148 (43.3%) | NE- 355 (17.1%) MW- 537 (25.8%) S- 840 (40.4%) W- 346 (16.7%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 87 (13.7%) MW- 100 (15.7%) S- 246 (38.6%) W- 204 (32.0%) | NE- 317 (17.8%) MW- 477 (26.8%) S- 699 (39.2%) W- 290 (16.3%) | <0.01 ~~ | NE- 53 (19.3%) MW- 31 (11.3%) S- 63 (23.0%) W- 127 (46.4%) | NE- 351 (16.4%) MW- 546 (25.4%) S- 882 (41.1%) W- 367 (17.1%) | <0.01 ~~ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kung, A.; Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; Holaday, L.W.; McKendrick, K.; Siu, A.L. Alternative Approaches to Characterizing Disparate Care by Race, Ethnicity, and Insurance Between Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101514

Kung A, Chen Y, Liu B, Holaday LW, McKendrick K, Siu AL. Alternative Approaches to Characterizing Disparate Care by Race, Ethnicity, and Insurance Between Hospitals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101514

Chicago/Turabian StyleKung, Alina, Yingtong Chen, Bian Liu, Louisa W. Holaday, Karen McKendrick, and Albert L. Siu. 2025. "Alternative Approaches to Characterizing Disparate Care by Race, Ethnicity, and Insurance Between Hospitals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101514

APA StyleKung, A., Chen, Y., Liu, B., Holaday, L. W., McKendrick, K., & Siu, A. L. (2025). Alternative Approaches to Characterizing Disparate Care by Race, Ethnicity, and Insurance Between Hospitals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101514