Then, Now, Next: Unpacking the Shifting Trajectory of Social Determinants of Health

Abstract

1. Early Underpinnings

2. Social Determinants of Health in Practice

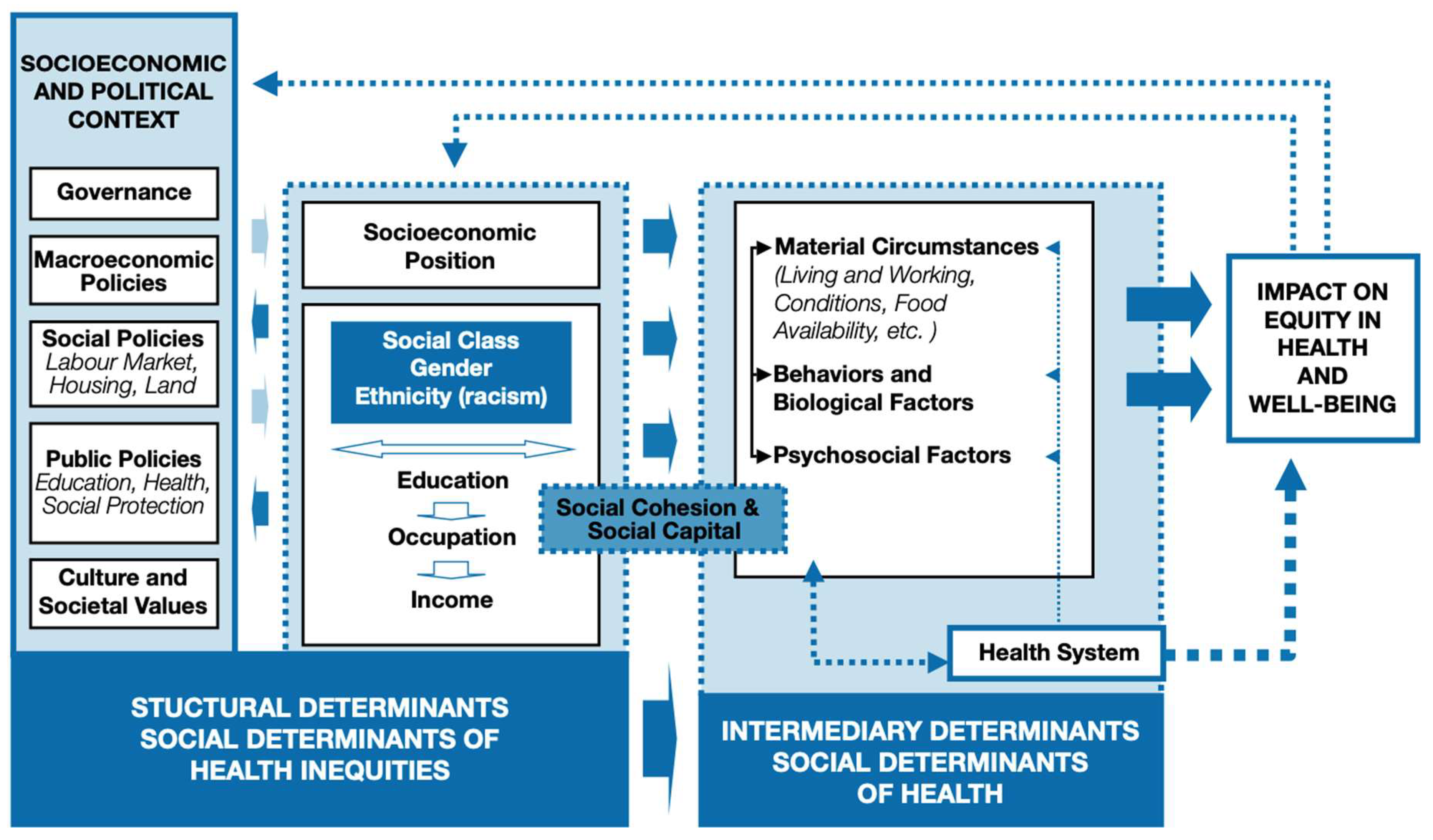

3. Theories, Models, and Frameworks

4. Research Gaps and Stimulating Research

5. Shifting Language and Trajectory (Landscape)

6. Evolving Framing and Political Dynamics of SDOH

7. Pedagogical Strategies in Teaching SDOH

8. Stimulating Research on SDOH

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osmick, M.J.; Wilson, M. Social determinants of health—Relevant history, a call to action, an organization’s transformational story, and what can employers do? Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Tehranifar, P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S28–S40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Advancing Health Equity by Addressing the Social Determinants of Health in Family Medicine (Position Paper). 2019. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/social-determinants-health-family-medicine-position-paper.html (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Marmot, M.G.; Smith, G.D.; Stansfeld, S.; Patel, C.; North, F.; Head, J.; White, I.; Brunner, E.; Feeney, A. Health inequalities among British civil servants: The Whitehall II study. In Stress and the Brain; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013; pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L.F.; Kawachi, I. (Eds.) Social Epidemiology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.; Wilkinson, R. Social Determinants of Health. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. 2010. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44489/9789241500852_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Braveman, P.; Forefront Group. A New Definition of Health Equity to Guide Future Efforts and Measure Progress. 22 June 2017. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/new-definition-health-equity-guide-future-efforts-and-measure-progress (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/about/priorities/why-is-addressing-sdoh-important.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Gottlieb, L.M.; Hessler, D.; Long, D.; Laves, E.; Burns, A.R.; Amaya, A.; Sweeney, P.; Schudel, C.; Adler, N.E. Effects of Social Needs Screening and In-Person Service Navigation on Child Health. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, e162521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarce, J. Health Inequity in the United States: A Primer; Penn Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, J.; Kleinhenz, G.; Smith, J.M.; Chaney, R.A.; Moxley, V.B.; Naranjo, P.G.D.; Stone, S.; Hanson, C.L.; Redelfs, A.H.; Novilla, M.L.B. Do healthcare providers consider the social determinants of health? Results from a nationwide cross-sectional study in the United States. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Flaubert, J.; Menestrel, S.; Williams, D.; Wakefield, M. Social determinants of health and health equity. In The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573923/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alley, D.E.; Asomugha, C.N.; Conway, P.H.; Sanghavi, D.M. Accountable Health Communities—Addressing Social Needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billioux, A.; Verlander, K.; Anthony, S.; Alley, D. Standardized Screening for Health-Related Social Needs in Clinical Settings: The Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool. NAM Perspect. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO); Commission on Social Determinants of Health. A Conceptual Framework for Action on Social Determinants of Health. 2007. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Tanaka, Y. Social Selection and the Evolution of Animal Signals. Evolution 1996, 50, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, X.; You, H. Social causation, social selection, and economic selection in the health outcomes of Chinese older adults and their gender disparities. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 24, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton-Jeangros, C.; Cullati, S.; Sacker, A.; Blane, D. A Life Course Perspective on Health Trajectories and Transitions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrucci, B.C.; Auerbach, J. Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. Health Aff. Forefr. 2019. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/meeting-individual-social-needs-falls-short-addressing-social-determinants-health (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Frank, J.; Abel, T.; Campostrini, S.; Cook, S.; Lin, V.K.; McQueen, D.V. The Social Determinants of Health: Time to Re-Think? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; French, D.; Black, B.; Kho, A.N. Cohort study examining social determinants of health and their association with mortality among hospitalised adults in New York and California. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e001266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.A.; Porticella, N.; Liu, J.; Taylor, T.; Michener, J.; Barry, C.L.; Nagler, R.H.; Gollust, S.; Moore, S.T.; Fowler, E.F.; et al. Beyond fear of backlash: Effects of messages about structural drivers of COVID-19 disparities among large samples of Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White Americans. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 377, 118096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health; Board on Global Health; Institute of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984; ISBN 9780132952613. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. 2021. Available online: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/pdf/Essentials-2021.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Beard, K.V.; Sanderson, C.D. Racism: Dismantling the Threat for Health Equity and the Nursing Profession. Nurs. Econ. 2022, 40, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavloff, M.; Edge, D.S.; Kulig, J. A framework for nursing practice in rural and remote Canada. Rural. Remote Health 2022, 22, 7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Johnson, C.; Thimm-Kaiser, M.; Benzekri, A. Nurse-led approaches to address social determinants of health and advance health equity: A new framework and its implications. Nurs. Outlook 2023, 71, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Health Services and Primary Care Research Study: Comprehensive Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/healthsystemsresearch/hspc-research-study/research-gaps.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Walton, A.L. The limits of “social determinants of health” Language. Am. J. Nurs. 2023, 123, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurana, C.A.; Ion, H.W. Could Changing the Language from Social “Determinants” to Social “Dynamics” of Health Encourage Transformational Change? Acad. Med. 2025, 100, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern National Network. Key Themes and Takeaways. A Kern National Network Convening. May 2024. Available online: https://knncaringcharactermedicine.org/KNN/Resources/Convenings/2024-SDoH-Convening---Key-Themes-and-Takeaways.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Federal Register. Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing. 2025. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/29/2025-01953/ending-radical-and-wasteful-government-dei-programs-and-preferencing (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Staff, N.; NACHC. Social Drivers vs. Social Determinants Using Clear Terms. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI—Community Health Conference & Expo, Chicago, IL, USA, 17–19 August 2025; Available online: https://www.nachc.org/social-drivers-vs-social-determinants-using-clear-terms/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Krieger, N. Ecosocial Theory, Embodied Truths, and the People’s Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Social Determinants of Health. Chronic Disease Indicators. 5 February 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cdi/index.html (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Dawes, D. The Political Determinants of Health; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, D.E.; Amador, C.M.; Dunlap, N.J.; Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. The Political Determinants of Health: A Global Panacea for Health Inequities. 19 October 2022. Available online: https://journals.stfm.org/familymedicine/2022/january/br-jan22-lin/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Federal Register. Withdrawing the United States from the World Health Organization. 2025. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/29/2025-01957/withdrawing-the-unied-states-from-the-world-health-organization (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Federal Register. Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government. 2025. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/30/2025-02090/defending-women-fom-gender-ideology-extremism-and-restoring-biological-truth-to-the-federal (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Federal Register. Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation. 2025. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/02/03/2025-02194/protecting-children-fom-chemical-and-surgical-mutilation (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Federal Register. Improving Education Outcomes by Empowering Parents, States, and Communities. 2025. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/03/25/2025-05213/improving-educatio-outcomes-by-empowering-parents-states-and-communities (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Federal Register. Implementing the President’s “Department of Government Efficiency” Workforce Optimization Initiative. 2025. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/02/14/2025-02762/implementing-the-presidents-department-of-government-efficiency-workforce-optimization-initiative (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. World Report on Social Determinants of Health Equity. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/equity-and-health/world-report-n-social-determinants-of-health-equity (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Buh, A.; Kang, R.; Kiska, R.; Fung, S.G.; Solmi, M.; Scott, M.; Salman, M.; Lee, K.; Milone, B.; Wafy, G.; et al. Effect and outcome of equity, diversity and inclusion programs in healthcare institutions: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e085007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turban, J.L.; King, D.; Carswell, J.M.; Keuroghlian, A.S. Pubertal Suppression for Transgender Youth and Risk of Suicidal Ideation. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20191725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.E.; Cutler, D.M.; Fielding, J.E.; Galea, S.; Glymour, M.M.; Koh, H.K.; Satcher, D. Addressing social determinants of health and health disparities: A vital direction for health and health care. NAM Perspect. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylte, D.; Baumann, M.M.; O Kelly, Y.; Kendrick, P.; Ali, O.M.M.; Compton, K.; A Schmidt, C.; Kahn, E.; Li, Z.; La Motte-Kerr, W.; et al. Life expectancy by county and educational attainment in the USA, 2000–2019: An observational analysis. Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e136–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaj, M.; Henson, C.A.; Aronsson, A.; Aravkin, A.; Beck, K.; Degail, C.; Donadello, L.; Eikemo, K.; Friedman, J.; Giouleka, A.; et al. Effects of education on adult mortality: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e155–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarblog. The Social Determinants of Health: A Call for Transformative Policy Change. 2025. Available online: https://elgar.blog/2025/03/13/the-social-determinants-of-health-a-call-for-transformative-policy-change/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Mangold, K.A.; Williams, A.-L.; Ngongo, W.; Liveris, M.; Brown, A.E.C.; Adler, M.D.; Campbell, M. Expert Consensus Guidelines for Assessing Students on the Social Determinants of Health. Teach. Learn. Med. 2022, 35, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenerette, C.; Murillo, C.L.; Chew, A.Y.; Barksdale, D.J. Simulation in PhD Programs to Prepare Nurse Scientists as Social Justice Advocates. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2021, 42, E60–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiles, T.; Jasmin, H.; Nichols, B.; Haddad, R.; Renfro, C.P. A Scoping Review of Active-Learning Strategies for Teaching Social Determinants of Health in Pharmacy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 8241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westberg, S.M.; Bumgardner, M.A.; Lind, P.R. Enhancing cultural competency in a college of pharmacy curriculum. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2005, 69, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devraj, R.; Butler, L.M.; Gupchup, G.V.; Poirier, T.I. Active-learning strategies to develop health literacy knowledge and skills. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2010, 74, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.; Jacobson, D.; McCarthy, M. Impact of a social justice course in graduate nursing education. Nurse Educ. 2022, 47, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray-García, J.L.; Ngo, V.; Yonn-Brown, T.A.; Hosley, D.H.; Ton, H. California’s Central Valley: Teaching Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Humility Through an Interprofessional, Overnight Road Trip. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2022, 33, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). Guiding Principles for Competency-Based Education and Assessment. 2023. Available online: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Essentials/Guiding-Principles-for-CBE-Assessment.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Li, C.; Guo, J.; Bian, J.; Becich, M.J. Advancing social determinants of health research and practice: Data, tools, and implementation. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2025, 9, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tilmon, S.; Nyenhuis, S.; Solomonides, A.; Barbarioli, B.; Bhargava, A.; Birz, S.; Bouzein, K.; Cardenas, C.; Carlson, B.; Cohen, E.; et al. Sociome Data Commons: A scalable and sustainable platform for investigating the full social context and determinants of health. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 7, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, W.G.; Gasman, S.; Beccia, A.L.; Fuentes, L. The health equity explorer: An open-source resource for distributed health equity visualization and research across common data models. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 8, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Socrates, V.; Gilson, A.; Safranek, C.; Chi, L.; Wang, E.A.; Puglisi, L.B.; Brandt, C.; Taylor, R.A.; Wang, K. Identifying incarceration status in the electronic health record using large language models in emergency department settings. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 8, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.R.; Fu, S.; Wen, A.; Corbeau, A.; Henderson, D.; Hilsman, J.; Oniani, D.; Wang, Y. The ENACT network is acting on housing instability and the unhoused using the open health natural language processing toolkit. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 8, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.C.; Sehgal, S.; Phuong, J.; Bahroos, N.; Starren, J.; Wilcox, A.; Meeker, D. Development of a social and environmental determinants of health informatics maturity model. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 7, e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wallington, S.F.; Feger, C. Then, Now, Next: Unpacking the Shifting Trajectory of Social Determinants of Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101541

Wallington SF, Feger C. Then, Now, Next: Unpacking the Shifting Trajectory of Social Determinants of Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101541

Chicago/Turabian StyleWallington, Sherrie Flynt, and Calistine Feger. 2025. "Then, Now, Next: Unpacking the Shifting Trajectory of Social Determinants of Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101541

APA StyleWallington, S. F., & Feger, C. (2025). Then, Now, Next: Unpacking the Shifting Trajectory of Social Determinants of Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101541