Understanding Family Functioning as a Protective Factor for Adolescents’ Mental Health from the Parental Perspective: Photovoice in Rural Communities of Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Theoretical Perspective

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Data Collection in FGDs and Photovoice

2.7. FGD Procedure

2.8. Photovoice Procedure

2.9. Interview Guide

2.10. Data Analysis

2.11. Rigor and Quality Guarantee

2.12. Ethical and Legal Aspects of the Study

3. Results

3.1. Family Strengths as a Protective Factor

3.2. Positive Support Within the Family

“I think it would be having a little patience and affection. We must be tolerant and teach them. As one is older it is like giving to the youngest, giving him more affection.” (SP6-FG4).

“To be loved, to be listened to, to be helped or not to get too angry.” (SP2-FG2).

“Adolescents will be happier if there is understanding at home and if they are helped with whatever they need.” (SP5-FG1)

“It is the part that we must give to our children: to talk, advise, and help.” (SP1-FG4)

“If we support them through thick and thin, with advice or money, they will move forward. That is why it is good to support them. And if they are not supported, then they will fall behind in their studies. And studying is the main thing, because now without studying they are nothing.” (SP4-FG4)

3.3. Adequate Parental Supervision

“They didn’t want anything (teenagers), they didn’t want to do their schoolwork, that’s why they lost the year [did not advance to the next school grade]. So, when I recovered, I went to talk to his teachers to find out what was happening. All my children attended the same school, so the teachers already knew me, but when these two missed the year [failed the grade], I explained my health situation, everything I went through, and they told me that we should try to have more communication. They did not know them.” (S6-FG4).

“Encourage them to study, know what they are doing, so they do not get married so quickly.” (SP3-FG5).

3.4. Family Communication

“Family dialogue is positive.” (SP1-FG1).

“Communication, talking to children.” (SP2-FG2).

“You always must talk with them. It is necessary communication between parents and adolescents”. (SP-FG3).

“I always have the idea in my home that at the table we eat, in the morning or at night, I talk to my children about their things.” (SP5-FG4).

“Now I think about the home, the family, it is always the dialogue for the children and the dialogue for the home, because if you go the hard way, you will not achieve anything like that in a short time.” (SP2-FG4).

“Sometimes families suffer from things that happen to teenagers.” (SP5-FG3).

“When there is trust, the child can tell his father or mother. I think that there one could realize what is happening with them to give them advice.” (SP1-FG5).

“When I see them, I always ask them what’s happening? In health problems more than anything or I insist that they tell us the other things that happen to them. Then they say yes, mom, I’m missing something. So, I say don’t worry, we’ll figure it out.” (SP6-FG4).

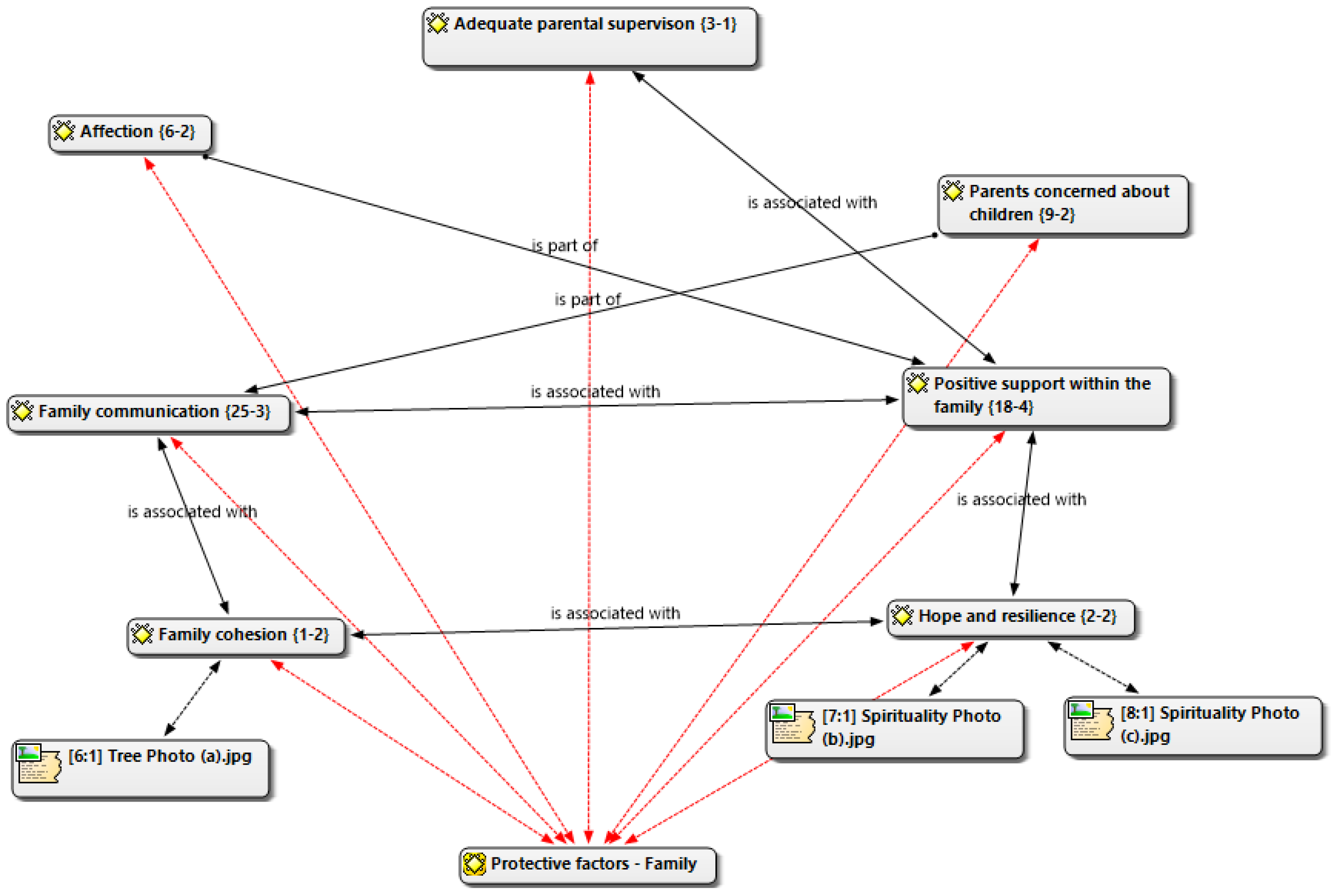

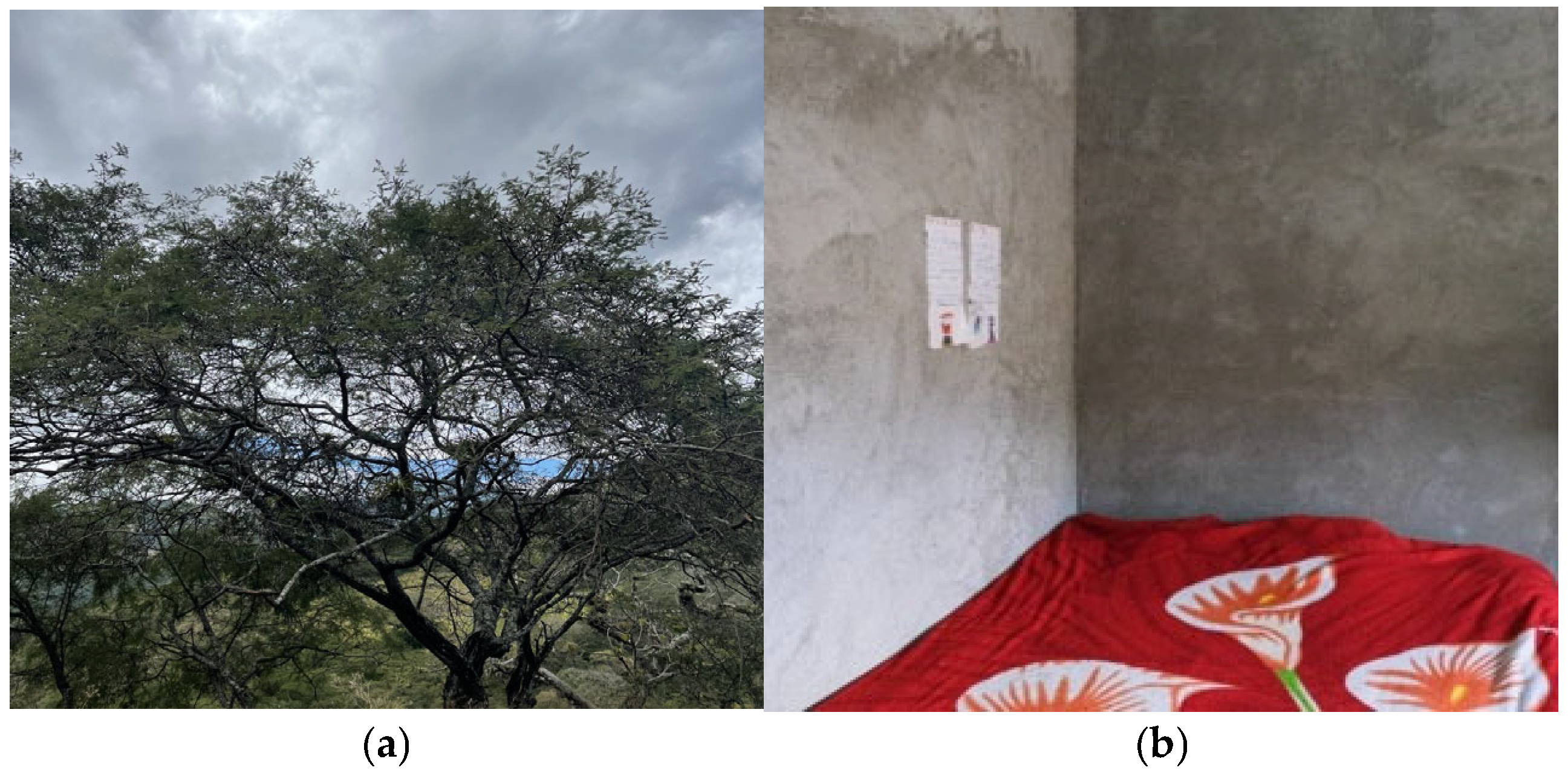

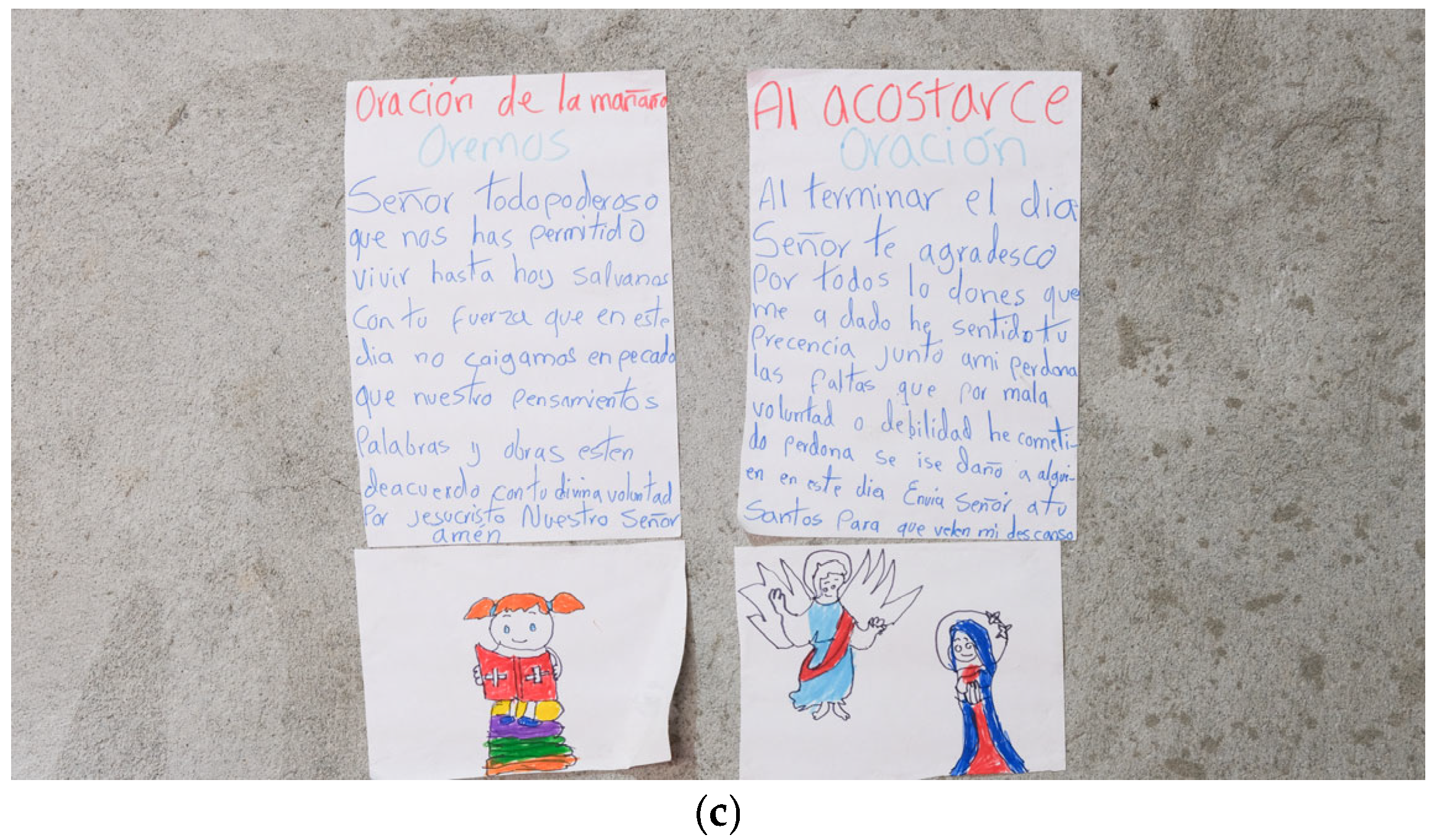

3.5. Photovoice Component

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FGDs | Five Focus Group Discussions |

| LMIC | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- Redit, C.; Ho, P.; Ograph, T.; Isio, V. Mental health—A foundational and universal human right. Nat. Ment. Health 2023, 1, 693–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Day: Mental Health Is a Universal Human Right. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/detail/10-10-2023-world-mental-health-day-mental-health-is-a-universal-human-right (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Marchi, M.; Alkema, A.; Xia, C.; Thio, C.H.L.; Chen, L.-Y.; Schalkwijk, W.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Ferrari, S.; Pingani, L.; Kweon, H.; et al. The impact of poverty on mental illness: Emerging evidence of a causal relationship. Medrxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.; O’Neal, L.; Kersey, E.; Nielsen, A.; Coker, K.; Forthun, L. A Community-Based Approach to Supporting the Mental Health of Rural Youth. EDIS 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, G.; Renzi, E.; Longobucco, Y.; Cianciulli, A.; Rosso, A.; Marzuillo, C.; De Vito, C.; Villari, P.; Massimi, A. State of the Art on Family and Community Health Nursing International Theories, Models and Frameworks: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeydani, A.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F.; Hosseini, M.; Zohari-Anboohi, S. Community-based nursing: A concept analysis with Walker and Avant’s approach. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesman, E.; Vreeker, A.; Hillegers, M. Resilience and mental health in children and adolescents: An update of the recent literature and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Duan, X.; Yan, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wu, T.; Xie, Y.; Yang, B.X.; Luo, D.; Liu, L. Family Functioning and Adolescent Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Bullying Victimization and Resilience. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Jespersen, J.E.; Cosgrove, K.T.; Ratliff, E.L.; Kerr, K.L. Parent Education: What We Know and Moving Forward for Greatest Impact. Fam. Relat. 2020, 69, 520–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rava, J.; Hotez, E.; Halfon, N. The role of social capital in resilience among adolescents with adverse family environments. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2023, 53, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhou, X.; Shek, D.T.L.; Wang, Y. Family Resilience and Adolescent Mental Health in Chinese Families: The Mediating Role of Personal Strengths. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, M. The relationship between family communication and family resilience in Chinese parents of depressed adolescents: A serial multiple mediation of social support and psychological resilience. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, L.; Bright, K.; Bassi, E.M.; Barker, M.; Hews-Girard, J.; Pintson, K.; Daniel, S.; Volcko, L.; Sidhu, S.; Greer, K.; et al. ‘Multi-stressed’: A qualitative study exploring the impact of the social determinants of health on access to digital mental health for youth and young adults in Alberta. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076251361327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enebeli, M.O.; Saint, V.; Hämel, K. Nurses’ health promotion practices in rural primary health care in Nigeria. A qualitative study. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baus, E.; Carrasco-Tenezaca, M.; Frey, M.; Medina-Maldonado, V. Risk Factors for the Mental Health of Adolescents from the Parental Perspective: Photo-Voice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, R.; Bhui, K. Analysing multimodal data that have been collected using photovoice as a research method. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, M.; Keiller, E.; Conneely, M.; Heritage, P.; Steffen, M.; Bird, V.J. A systematic scoping review of Photovoice within mental health research involving adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2023, 28, 2244043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Doesschate, T.; PERALTA, A.Q.; LOJANO, H.C.; Fajardo, V.; Flores, N.; Guachún, M.; Barten, F. Psychological and behavioral problems among left-behind adolescents. The case of Ecuador. Rev. La Fac. Cienc. Médicas 2012, 3, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Davila, S.A.; Martinez, A.; Medrano, A.S. Navigating familial stressors and material needs: Examining resilience and family cohesion as protective factors for rural Mexican adolescents. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, A.O.; Madkins, J.; McMaughan, D.; Schulze, A. Mental Health and Mental Disorders: A Rural Challenge; Bolin, J.N., Bellamy, G., Ferdinand, A.O., Eds.; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, V.; Bowie, M.; Bales, D.; Scheyett, A.; Thomas, R.; Cook, G. Cooperative Extension offices as mental health hubs: A social ecological case study in rural Georgia, United States. SSM Ment. Health 2023, 3, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.; An, I.S. Review of studies applying Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory in international and intercultural education research. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1233925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newland, L.A.; Mourlam, D.J.; Strouse, G.A. Rural Children’s Well-Being in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perspectives from Children in the Midwestern United States. Int. J. Child Maltreatment Res. Policy Pract. 2023, 6, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahey, M.; Wright, L.M. Application of the Calgary Family Assessment and Intervention Models: Reflections on the Reciprocity Between the Personal and the Professional. J. Fam. Nurs. 2016, 22, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileski, M.; McClay, R.; Heinemann, K.; Dray, G. Efficacy of the Use of the Calgary Family Intervention Model in Bedside Nursing Education: A Systematic Review. J. Multidiscip. Heal. 2022, 15, 1323–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, V.M.; Fish, J.; Maudrie, T.L.; Hunter, A.M.; Tai Rakena, H.G.; Ullrich, J.S.; Clifford, C.; Crawford, A.; Brockie, T.; Walls, M.; et al. Centering Indigenous Knowledges and Worldviews: Applying the Indigenist Ecological Systems Model to Youth Mental Health and Wellness Research and Programs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reupert, A.; Hine, R.; Maybery, D. Working with rural families: Issues and responses when a family member has a mental illness. In Handbook of Rural, Remote, and Very Remote Mental Health; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hao, Y.; Cui, N.; Wang, Z.; Lyu, P.; Yue, L. Parenting and parenting resources among Chinese parents with children under three years of age: Rural and urban differences. BMC Prim. Care 2023, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modderman, C.; Downey, H. Special issue: Health and well-being services for children and young people (ages 0–24) in rural and remote communities. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2023, 31, 1041–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, N.; Douglas, P.; Keaver, L. Meaning of nutrition for cancer survivors: A photovoice study. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2024, 7, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Gordillo, M.J.; Bates, B.R.; Vivat, B. The (im)possibility of being a breastfeeding working mother: Experiences of Ecuadorian healthcare providers. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, 1153679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Kozak, N.; Black, A. Photovoice Exploration of Frontline Nurses’ Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 55, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, G.M.; Lydon-Staley, D.M. Implications of family cohesion and conflict for adolescent mood and well-being: Examining within-and between-family processes on a daily timescale. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 1672–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina Moreno, P.; Fernández Gea, S.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. The Role of Family Functionality and Its Relationship with Psychological Well-Being and Emotional Intelligence in High School Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Maldonado, V. Enfermería familiar, enfoques, teoría y modelos para la atención. In Cuidado de Enfermería en el Núcleo Familiar: Reflexiones Teóricas y Aplicación de Casos, 1st ed.; Francisco Pérez, J., Ed.; EdiPUCE: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, A.H.; Keevers, Y.; Kaouar, S.; Kimonis, E.R. Conception and Development of the Warmth/Affection Coding System (WACS): A Novel Hybrid Behavioral Observational Tool for Assessing Parent-to-Child Warmth. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 51, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. The Relationship between Parental Emotional Warmth and Rural Adolescents’ Hope: The Sequential Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Prosocial Behavior. J. Genet. Psychol. 2023, 184, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, C.C.; Howell, K.H.; Mandell, J.E.; Hasselle, A.H.; Thurston, I.B. Spirituality and Parenting among Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riany, Y.E.; Haslam, D.M.; Sanders, M. Parental Mood, Parenting Style and Child Emotional and Behavioural Adjustment: Australia-Indonesia Cross-Cultural Study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 2331–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstadt, M. The Role of Mental Health Apps (MHapps) in Furthering Progress on SDG3: A Case for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration. In Integrated Science for Sustainable Development Goal 3; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Integrated Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 25, pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Papola, D.; Barbui, C.; Patel, V. Leave No One Behind: Rethinking Policy and Practice at the National Level to Prevent Mental Disorders. Ment. Health Prev. 2024, 33, 200317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamambang, R.; Kusi-Mensah, K.; Bella-Awusah, T.; Ogunmola, O.; Afolayan, A.; Toska, E.; Hertzog, L.; Rudgard, W.; Evans, R.; Stöeckl, H.; et al. Two are Better Than One but Three is Best: Fast-Tracking the Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Among In-School Adolescents in Nigeria. Child Indic. Res. 2024, 17, 2219–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzamarski, C.; de Steiguer, A.; Omari, F.; Hellmuth, J.; Walters, A.S. Accessing Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons from Western Kenya. In Innovations in Global Mental Health; Okpaku, S.O., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 971–986. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Holtmaat, K.; Verdonck-De Leeuw, I.M.; Koole, S.L. Chinese college students’ mental health during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic: The protective role of family functioning. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1383399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palimaru, A.I.; Dong, L.; Brown, R.A.; D’Amico, E.J.; Dickerson, D.L.; Johnson, C.L.; Troxel, W.M. Mental health, family functioning, and sleep in cultural context among American Indian/Alaska Native urban youth: A mixed methods analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Deductive Category Assignments | Definition | Anchor Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Family strengths as a protective factor | Positive attitudes, values or beliefs. Conflict resolution skills. Good mental, physical, spiritual and emotional health. | ‘Having effective communication with the children’; ‘being attentive to their needs’; ‘giving them love’. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medina-Maldonado, V.; Carrasco-Tenezaca, M.; Frey, M.; Baus-Carrera, E. Understanding Family Functioning as a Protective Factor for Adolescents’ Mental Health from the Parental Perspective: Photovoice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101471

Medina-Maldonado V, Carrasco-Tenezaca M, Frey M, Baus-Carrera E. Understanding Family Functioning as a Protective Factor for Adolescents’ Mental Health from the Parental Perspective: Photovoice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101471

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedina-Maldonado, Venus, Majo Carrasco-Tenezaca, Molly Frey, and Esteban Baus-Carrera. 2025. "Understanding Family Functioning as a Protective Factor for Adolescents’ Mental Health from the Parental Perspective: Photovoice in Rural Communities of Ecuador" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101471

APA StyleMedina-Maldonado, V., Carrasco-Tenezaca, M., Frey, M., & Baus-Carrera, E. (2025). Understanding Family Functioning as a Protective Factor for Adolescents’ Mental Health from the Parental Perspective: Photovoice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101471