A Path Analysis Study on the Influence of Social Norms on Substance Use Severity: Focusing on People Who Use Cannabis, Narcotics, and Psychotropic Substances in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To identify the general characteristics, social norms, health beliefs, and severity of substance use among people of Republic of Korea who use cannabis, narcotics, and psychotropic substances

- (2)

- To analyze the effects of social norms on substance use severity, mediated by health beliefs among people of Republic of Korea who use cannabis, narcotics, and psychotropic substances.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Analysis

Main Variables

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation of Two Groups: People Who Use Cannabis and Narcotics and People Who Use Psychotropic Substances

3.3. The Impact of Social Norms and Health Belief Characteristics on Substance Use Severity

3.3.1. Goodness of Fit

3.3.2. Results of the Path Analysis of Social Norms and Health Beliefs to Health Beliefs and Severity of Substance Use

3.4. The Direct and Indirect Effect Decomposition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Supreme Prosecutors Office. 2023 Drug Control in Korea; Supreme Prosecutors Office: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, H.; Kim, S.; Hong, H.; Lee, J.; Shin, Y.J. Exploring the Influencing Factors of Entry into Social Rehabilitation Services through the Recovery Support Experience of Recovery Counselors Working in the Area of Drug Rehabilitation Services: Using Focus Group Interview. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2023, 23, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.; Neighbors, C.; Larimer, M.E. Social Norms and Substance Use: How Social Influence Shapes Behavior in the United States. Subst. Use Misuse 2021, 56, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Jansen, A.P. The Role of Social Media in Shaping Attitudes Toward Substance Use Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Addict. Behav. 2022, 112, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z.; King, D.L. The Role of Digital Platforms in Shaping Substance Use Norms: Implications for Risk Perception. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2023, 37, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y. Stigmatization and Legal Consequences: The Social and Legal Implications of Substance Use in China. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 77, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q. Social Exclusion and Substance Use in China: The Impact of Cultural Stigma and Legal Repercussions. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Digital Divide and Rural-Urban Disparities in access to Substance Use Disorder Treatment in China. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2023, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Kim, B.C.; Yamaguchi, H. The Stigma of Substance Abuse in Japan: A Qualitative Study on Attitudes Toward Individuals with Substance Use Disorders. Asian Pac. J. Public Health 2019, 31, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T. The Societal Perception of Substance Use and its Consequences in Japan: A Cultural Perspective. Asian J. Addict. Stud. 2021, 29, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, H.G. The Criminalization of Addiction in South Korea: How Societal Attitudes Hinder Treatment Access. Int. J. Addict. Recovery 2020, 8, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Choi, K.J.; Lee, M.H. The Stigma of Substance Use and Its Impact on Treatment Access in South Korea. Addict. Res. Theory 2022, 30, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Lee, S.J. Legal Punishment and Treatment of Individuals with Substance Use Disorders in South Korea. J. Korean Addict. Stud. 2021, 22, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Jang, W.Y.; Lee, M.H. Legal Penalties and Stigma as Barriers to Substance Use Disorder Treatment in South Korea. J. Addict. Med. 2024, 45, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimore, P.K.; Steffey, D.M. The Impact of Drug courts on Recidivism: A Meta-Analysis. J. Exp. Criminol. 2018, 14, 209–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumbourou, J.W.; Williams, I.; Letcher, P. Effectiveness of Prevention Programs for Substance Use in Adolescents. Addict. Res. Theory 2017, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Compulsory Drug Treatment and Rehabilitation in East and Southeast Asia; UNDOC: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022; Available online: https://www.unodc.org/roseap/en/2022/01/compulsory-treatment-rehabilitation-east-southeast-asia.html (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Lee, S.H.; Baik, H.; Kim, J.W. Comparison of Seoul’s Drug Addiction Policy and Social Rehabilitation Service Development with Overseas Cases; Seoul Metropolitan City Seoul Welfare Foundation: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; Available online: http://125.61.91.238:8080/SynapDocViewServer/viewer/doc.html?key=87a6196086ce4b5c8935741a489b5d26&convType=html&convLocale=ko_KR&contextPath=/SynapDocViewServer/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Son, A.R.; Kim, M.H.; Yang, J.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Bae, J.H.; Eom, S.H.; Seo, Y.K. The National Survey of the Drug and Substance Abuse Attitude: An Initial Scale Development of Drug Attitude and the Drug Abuse Screening Test; Ministry of Food and Drug Safety∙Sahmyook University Industry-Academic Cooperative Foundation: Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Principles of Topological Psychology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.; Park, G.R.; Park, C.H.; Jang, M.; Han, E.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Jung, J.H.; Son, A.; Yang, M.Y.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Improvement Research on Drug Addiction Treatment, Rehabilitation, and Abuse Prevention; Ministry of Food and Drug Safety: Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. A Review on the Operational Status of the National Institute of Mental Health in America & Japan. Korean Public Health Res. 2009, 35, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Lim, H.W.; Jung, H.S.; Chun, Y.H.; Cho, S.J.; Jang, O.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, M.H.; Jeon, Y.R.; Osan, Y. The Survey of Drug Users in Korea 2021; National Center for Mental Health: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E. Consideration of criminal justice intervention on crimes related with addictions. J. Law Politics Res. 2017, 17, 57–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.L. Revising Sample Size and Number of Parameter Estimates: Some Support for the N;q Hypothesis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Cho, M.J. Gender-specific factors predicting substance abuse: In search of health communication strategies for high risk group. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2012, 55, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.A. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Validating a Korean Version of the Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 (DAST-10). J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2014, 40, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yang, D.H.; Moon, J.Y. A Qualitative Content Analysis on Relapse Experience of Drug Addicts. Correct. Rev. 2016, 70, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Kim, Y. A Study on Countermeasures Against Increasing Drug Offenders in Their Teens and 20s; Supreme Prosecutors Office: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, M.; Jang, C. Comparison of Service Delivery Systems in Korea and Japan on Drug Addiction. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 12, 688–696. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.; An, H.; Kim, S. Study on the Implications of the Countermeasures against Drug Abuse Crimes in Singapore. J. Law 2020, 30, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Kim, J. Effective Treatment for Drug Offenders on Probation; Korean Institute of Criminology: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.; Yoo, S. Analysis of Factors Affecting the Effectiveness of Preventive Education for Juvenile Drug Crimes: Focusing on the Perception of Scientific Investigators of the Seoul Metropolitan Police. J. Police Policies 2021, 35, 73–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winddle, J. Drug and Drug Policy in Thailand. In Improving Global Drug Policy: Comparative Perspectives and UNGASS 2016; Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/WindleThailand-final.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Park, J. International Case and Introduction for Preventing Recidivism of Drug Offenders. Chungang Law Rev. 2017, 19, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. A Study on the Responses to the Analysis of the Public Awareness of the Seriousness of Narcotics; Korean National Security and Public Safety Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, G.W. A Study on the Institutional Counter-measures against the New Drugs by the Characteristics. Korean Law Assoc. 2019, 76, 273–295. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | 1. Social Norms | 2. Health Beliefs | 3. Severity of Substance Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social norms | 1 | −0.043 | 0.185 | |||

| 2. Health beliefs | 0.433 ** | 1 | 0.054 | |||

| 3. Severity of substance use | 0.109 | 0.150 * | 1 | |||

| Variables | A | B | A | B | A | B |

| Mean | 3.43 | 3.35 | 3.40 | 3.52 | 4.08 | 4.58 |

| SD | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.69 | 2.50 | 2.89 |

| Skewness | 0.73 | −0.35 | −2.04 | −0.51 | 9.04 | 0.00 |

| Kurtosis | 1.25 | 3.20 | 9.04 | 1.26 | −0.33 | −1.06 |

| Measure | χ2 | df | Normed | TLI | CFI | NFI | IFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO90 | HI90 | ||||||||

| Comparison model | 4.341 | 2 | 2.170 | 0.835 | 0.945 | 0.911 | 0.950 | 0.063 | |

| 0.000 | 0.145 | ||||||||

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | ||||

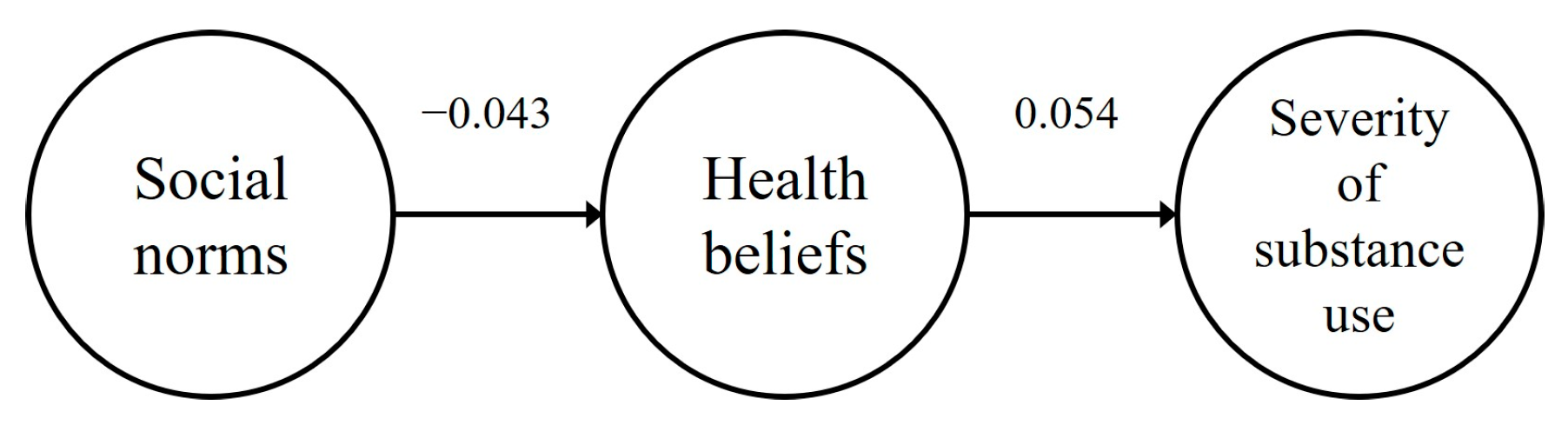

| (A) Social norms → Health beliefs | −0.057 | −0.043 | 0.128 | −0.445 | 0.656 |

| (A) Health beliefs → Severity of substance use | 0.219 | 0.054 | 0.385 | 0.568 | 0.570 |

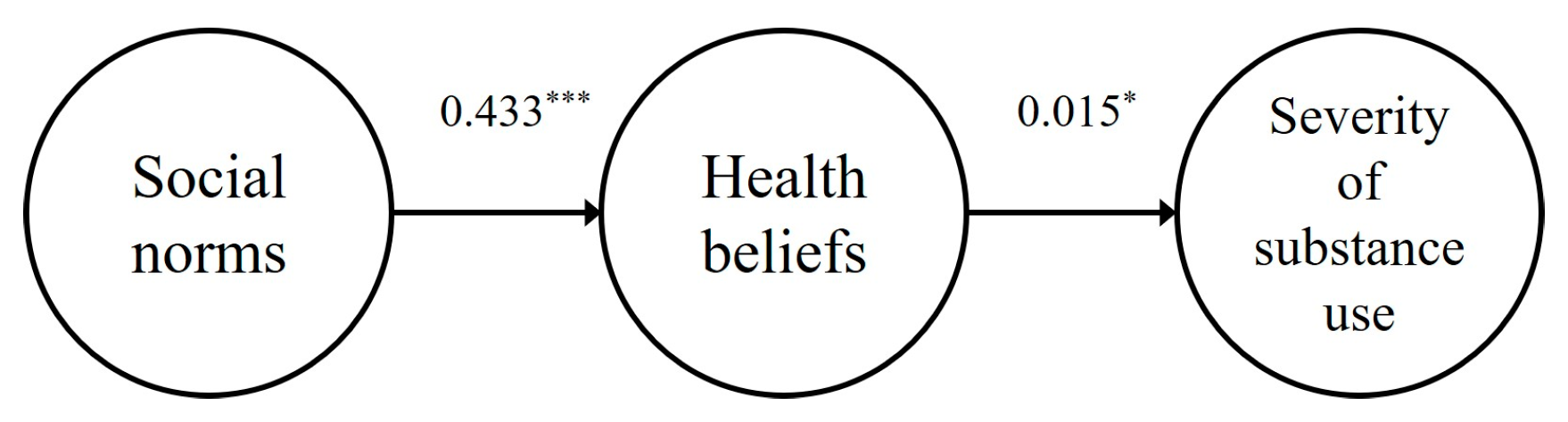

| (B) Social norms → Health beliefs | 0.540 | 0.433 | 0.082 | 6.612 *** | 0.0009 |

| (B) Health beliefs → Severity of substance use | 0.630 | 0.150 | 0.301 | 2.093 * | 0.036 |

| Path | Estimate (β) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | |

| (A) Social norms → Health beliefs | −0.043 | - | −0.043 |

| (A) Social norms → Severity of substance use | - | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| (A) Health beliefs → Severity of substance use | 0.054 | - | 0.054 |

| (B) Social norms → Health beliefs | 0.433 *** | - | 0.433 *** |

| (B) Social norms → Severity of substance use | - | 0.065 * | 0.065 * |

| (C) Health beliefs → Severity of substance use | 0.150 * | - | 0.150 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Baik, H.-U.; Lee, J.; Shin, Y. A Path Analysis Study on the Influence of Social Norms on Substance Use Severity: Focusing on People Who Use Cannabis, Narcotics, and Psychotropic Substances in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010015

Lee S, Baik H-U, Lee J, Shin Y. A Path Analysis Study on the Influence of Social Norms on Substance Use Severity: Focusing on People Who Use Cannabis, Narcotics, and Psychotropic Substances in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Songhee, Hyung-Ui Baik, Juyong Lee, and Yunjae Shin. 2025. "A Path Analysis Study on the Influence of Social Norms on Substance Use Severity: Focusing on People Who Use Cannabis, Narcotics, and Psychotropic Substances in South Korea" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010015

APA StyleLee, S., Baik, H.-U., Lee, J., & Shin, Y. (2025). A Path Analysis Study on the Influence of Social Norms on Substance Use Severity: Focusing on People Who Use Cannabis, Narcotics, and Psychotropic Substances in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010015