Depressive Symptoms Among South African Construction Workers: Associations with Demographic, Social and Work-Related Factors, and Substance Use †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Depression and Depressive Symptoms

2.2. Age, Ethnicity, and Education

2.3. Relationship Status, Living Arrangements and Work Status

2.4. Alcohol Consumption, Drug Use/Abuse, and Depressive Symptoms

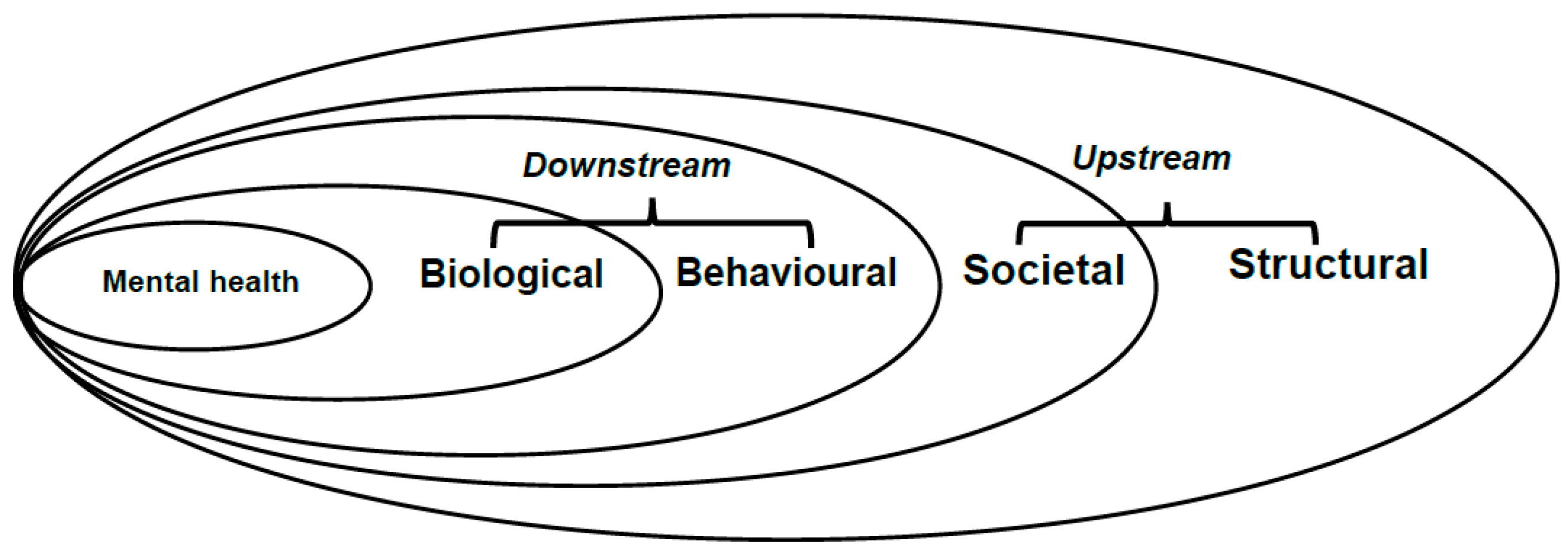

3. The Conceptual Research Model

4. Research Method

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Instrument and Measures

4.3. Participants and Setting

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Data Cleaning

5.2. Analysis Method

6. Results

6.1. Participant Characteristics

6.2. Bivariate Relationships Between Depressive Symptoms and Characteristics of Participants

6.3. Binomial Logistic Regression Analysis

7. Discussion

7.1. Associations Between Demographic Factors and Presence of Depressive Symptoms

7.2. Associations Between Social and Work-Related Factors and Presence of Depressive Symptoms

7.3. Association Between Substance Use and Presence of Depressive Symptoms

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Indicator Metadata Registry List. The Global Health Observatory. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Pincus, H.A.; Pettit, A.R. The societal costs of chronic major depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 62, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. Depression Health Topics. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Boschman, J.S.; van der Molen, H.F.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Psychosocial work environment and mental health among construction workers. Appl. Ergon. 2013, 44, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, H.B.; Caban-Martinez, A.; Onyebeke, L.C.; Sorensen, G.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Reme, S.E. Construction workers struggle with a high prevalence of mental distress and this is associated with their pain and injuries. J. Occup. Environ. Med. Am. Coll. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maskari, F.; Shah, S.; Al-Sharhan, R.; Al-Haj, E.; Al-Kaabi, K.; Khonji, D.; Schneider, J.D.; Nagelkerke, N.J.; Bernsen, R. Prevalence of depression and suicidal behaviors among male migrant workers in United Arab Emirates. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, J.; Hasan, A.; Kamardeen, I. Mental health challenges of manual and trade workers in the construction industry: A systematic review of causes, effects and interventions. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 1497–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. Suicide by Occupation, England: 2011 to 2015. 2017. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/suicidebyoccupation/england2011to2015 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Mates in Construction. Suicide in the Construction Industry. 2016. Available online: https://mates.org.au/media/documents/MIC-Annual-suicide-report-MIC-and-Deakin-University.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Chan, A.P.; Nwaogu, J.M.; Naslund, J.A. Mental ill-health risk factors in the construction industry: Systematic review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.C.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Darko, A.; Yang, J.Y.; Salihu, D. Prevalence and risk factors for poor mental health and suicidal ideation in the Nigerian construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 05022021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western Cape Department of Health and Wellness. Western Cape Burden of Disease Reduction Project; Final Report (Volume 1)-Overview and Executive Summaries (Vol. 2023); Western Cape Government: Cape Town, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders, Global Health Estimates; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Chi, S.; Lee, J.D.; Lee, H.-J.; Choi, H. Analyzing psychological conditions of field-workers in the construction industry. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 23, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; Atkinson, S.; Brown, S.S.; Haslam, R.A. Anxiety and depression in the workplace: Effects on the individual and organisation (a focus group investigation). J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 88, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Sprince, N.L.; Lewis, M.Q.; Burmeister, L.F.; Whitten, P.S.; Zwerling, C. Risk factors for work-related injury among male farmers in Iowa: A prospective cohort study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 43, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-J.; Jeong, B.-Y. Older Male Construction Workers and Sustainability: Work-Related Risk Factors and Health Problems. Sustainability 2001, 13, 13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Feldman, D.C. How do within-person changes due to aging affect job performance? J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varianou-Mikellidou, C.; Boustras, G.; Dimopoulos, C.; Wybo, J.-L.; Guldenmund, F.W.; Nicolaidou, O.; Anyfantis, I. Occupational health and safety management in the context of an ageing workforce. Saf. Sci. 2019, 116, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zwart, B.C.H.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; Duivenbooden, J.C.V. Senior workers in the Dutch construction industry: A search for age-related work and health Issues. Exp. Aging Res. 1999, 25, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.K.; Mokonogho, J.; Kumar, A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riolo, S.A.; Nguyen, T.A.; Greden, J.F.; King, C.A. Prevalence of depression by race/ethnicity: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 998–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, R.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Karlan, D.S.; Zinman, J. Social and economic correlates of depressive symptoms and perceived stress in South African adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, J.W.; Chia, C.; Koh, C.J.; Chua, B.W.; Narayanaswamy, S.; Wijaya, L.; Chan, L.G.; Goh, W.L.; Vasoo, S. Healthcare-seeking behaviour, barriers and mental health of non-domestic migrant workers in Singapore. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, K.; Natarajan, R.; Dasgupta, C. Prevalence and risk factors for depression, anxiety and stress among foreign construction workers in Singapore–A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 23, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.; Tyrovolas, S.; Koyanagi, A.; Chatterji, S.; Leonardi, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Koskinen, S.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Haro, J.M. The role of socio-economic status in depression: Results from the COURAGE (aging survey in Europe). BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: Resource multiplication or resource substitution? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1400–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, T.; Nakata, A.; Takahashi, M.; Hojou, M.; Haratani, T.; Nishikido, N.; Kamibeppu, K. Correlates of depressive symptoms among workers in small- and medium-scale manufacturing enterprises in Japan. J. Occup. Health 2009, 51, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulloch, A.G.M.; Williams, J.V.A.; Lavorato, D.H.; Patten, S.B. The depression and marital status relationship is modified by both age and gender. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 223, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPierre, T.A. Marital status and depressive symptoms over time: Age and gender variations. Fam. Relat. 2009, 58, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S.R. Marital status and mental health revisited: Examining the importance of risk factors and resources. Fam. Relat. 1999, 48, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, A.E.; Shuey, K.M.; Elder, J.; Glen, H. Cumulative advantage processes as mechanisms of inequality in life course health. Am. J. Sociol. 2007, 112, 1886–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.S.; Brooks, R.D.; Brown, S.; Harris, W. Psychological distress and suicidal ideation among male construction workers in the United States. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 65, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, S. From Control to Confusion: The Changing Role of Administration Boards in South Africa, 1971–1983; Shuter & Shooter: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Posel, D. Living alone and depression in a developing country context: Longitudinal evidence from South Africa. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.; Posel, D. Here to work: The socioeconomic characteristics of informal dwellers in post-apartheid South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2012, 24, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.; O’Leary, B.; Mutsonziwa, K. Measuring quality of life in informal settlements in South Africa. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 81, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.L.; Ho, A.H.Y.; Chi, I. Living alone and depression in Chinese older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, S.T.; Beach, S.R.; Musa, D.; Schulz, R. Living alone and depression: The modifying role of the perceived neighborhood environment. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlan, M.; Mayhew, C.; Bohle, P. The global expansion of precarious employment, work disorganization, and consequences for occupational health: A review of recent research. Int. J. Health Serv. 2001, 31, 335–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Hewison, K. Precarious work and the challenge for Asia. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazdins, L.; D’Souza, R.M.; Lim, L.L.-Y.; Broom, D.H.; Rodgers, B. Job strain, job insecurity, and health: Rethinking the relationship. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Smith, P.M.; Louie, A.M.; Quinlan, M.; Ostry, A.S.; Shoveller, J. Psychosocial and other working conditions: Variation by employment arrangement in a sample of working Australians. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2012, 55, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R. Are work stressors related to employee substance use? The importance of temporal context assessments of alcohol and illicit drug use. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkaware. Adults (18–75) in the UK Who Drink Alcohol for Coping Reasons; Drinkaware: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, P.; Edwards, P.; Lingard, H.; Cattell, K. Workplace stress, stress effects, and coping mechanisms in the construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140, 04013059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, J.; Ajayi, S.O.; Oyegoke, A.S. Alcohol and substance misuse in the construction industry. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 27, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, R.R.; Sawang, S. Construction workers’ well-being: What leads to depression, anxiety, and stress? J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04017100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Farrell, L. Alcohol and depression: Evidence from the 2014 health survey for England. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 180, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleton, A.; James, R.; Larsen, J. The Association between Mental Wellbeing, Levels of Harmful Drinking, and Drinking Motivations: A Cross-Sectional Study of the UK Adult Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.B.; Aasland, O.G.; Babor, T.F.; de la Fuente, J.R.; Grant, M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction 1993, 88, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.H.; Bergman, H.; Palmstierna, T.; Schlyter, F. Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur. Addict. Res. 2005, 11, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.D.; Ormrod, J.E. Practical Research: Planning and Design, 9th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.W. Missing Data: Analysis and Design; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, E.C.; Davies, T.; Lund, C. Validation of the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) in Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans populations in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Zhang, R.P. Psychometric properties of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and prevalence of alcohol use among SA site-based construction workers. Civ. Eng. Res. J. 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Zhang, R.P. Psychometric properties of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) and prevalence of drug use among SA site-based construction workers. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 29, 1692–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 28.0; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02111stQuarter2022.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- David, R.W.; Hector, M.G.; Harold, N.; Randolph, N.; Jamie, M.A.; Julie, S.; James, S.J. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin, L.I. The sociological study of stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1989, 30, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straker, G.; The Sanctuaries Counseling Team. The continuous traumatic stress syndrome: The single therapeutic interview. Psychol. Soc. 1987, 8, 46–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P.B.; Williams, D.R.; Stein, D.J.; Herman, A.; Williams, S.L.; Redmond, D.L. Race and psychological distress: The South African stress and health study. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.P.; Bowen, P.; Edwards, P. Determinants of Depressive Symptoms among Male Construction Workers in Cape Town, South Africa. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual ARCOM Conference, Leeds, UK, 4–6 September 2023; Tutesigensi, A., Neilson, C.J., Eds.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management (ARCOM): Leeds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Borra, C.; Gómez-García, F. Wellbeing at work and the great recession: The effect of others’ unemployment. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 1939–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, M.G.; Abrams, K.; Borchardt, K. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, A.; Renström, E.; Bäck, H.; Gustafsson, S. Measuring gender in surveys: Social Psychological Perspectives. In Proceedings of the Gender Diversity in Survey Research Workshop, Gothenburg, Sweden, 11–12 June 2018; Available online: http://www.genderfair.se/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Lindqvist-et-al-2018-Measuring-gender-in-surveys.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

| Characteristic | Response Options and Scoring |

|---|---|

| Age | Years |

| Ethnicity | ‘Black’ African = 1; ‘Other’ = 2 |

| Education | Primary or less = 1; Secondary exposed or completed = 2; Tertiary exposed or completed = 3 |

| Relationship status | Divorced, separated, widowed, or never married = 0; Married or living with a partner = 1 |

| Living arrangements | ‘Live alone = 1’; ‘Live with other adults; no children’ = 2; ‘Live with other adults and children < 18 yrs. = 3’; ‘Live only with children < 18 yrs. = 4’ |

| Work status | Casual or contract = 1; Permanent = 2 |

| Characteristics | Total | % | Absence of Depressive Symptoms | Presence of Depressive Symptoms | χ2 p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 496 | 100 | 406 | 81.9 | 90 | 18.1 | − |

| (Absence vs. presence) | |||||||

| Demographic, social and work-related characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.454 + |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.024 § | ||||||

| ‘Black’ African | 293 | 59.3 | 230 | 56.9 | 63 | 70.0 | |

| ‘Others’ | 201 | 40.7 | 174 | 43.1 | 27 | 30.0 | |

| Education (exposed or completed) | 0.052 | ||||||

| Primary | 86 | 18.2 | 63 | 16.2 | 23 | 27.4 | |

| Secondary | 309 | 65.5 | 259 | 66.8 | 50 | 59.5 | |

| Tertiary | 77 | 16.3 | 66 | 17.0 | 11 | 13.1 | |

| Relationship status | 0.342 § | ||||||

| Single | 248 | 51.8 | 208 | 52.8 | 40 | 47.1 | |

| Married / Long-term relationship | 231 | 48.2 | 186 | 47.2 | 45 | 52.9 | |

| Living arrangements | 0.025 § | ||||||

| Live alone | 90 | 19.2 | 66 | 17.0 | 24 | 29.6 | |

| Live with other adults; no children | 90 | 19.2 | 72 | 18.5 | 18 | 22.2 | |

| Live with other adults and children < 18 yrs. | 257 | 54.8 | 221 | 57.0 | 36 | 44.5 | |

| Live only with children < 18 yrs. | 32 | 6.8 | 29 | 7.5 | 3 | 3.7 | |

| Work status | 0.190 § | ||||||

| Casual or contract | 254 | 53.1 | 214 | 54.6 | 40 | 46.5 | |

| Permanent | 224 | 46.9 | 178 | 45.4 | 46 | 53.5 | |

| Behavioural characteristics | |||||||

| AUDIT score (alcohol consumption) | 0.009 § | ||||||

| Low risk of harm | 371 | 75.1 | 308 | 76.2 | 63 | 70.0 | |

| Moderate risk of harm | 86 | 17.5 | 72 | 17.8 | 14 | 15.6 | |

| High risk of harm | 18 | 3.6 | 14 | 3.5 | 4 | 4.4 | |

| Likely dependence | 19 | 3.8 | 10 | 2.5 | 9 | 10.0 | |

| DUDIT score (drug use/abuse) | 0.012 § | ||||||

| Absence of drug-related problems | 465 | 94.1 | 383 | 94.8 | 82 | 91.1 | |

| Possible drug-related problems | 25 | 5.1 | 20 | 5.0 | 5 | 5.6 | |

| High level of drug dependency | 4 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) + | ||

|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| ‘Black’ African | - | - |

| ‘Others’ | 1.90 * | 1.04–3.47 |

| Education (exposed or completed) | ||

| Primary | - | - |

| Secondary | 2.99 * | 1.21–7.41 |

| Tertiary | 1.26 | 0.57–2.79 |

| Social and work-related characteristics | ||

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | - | - |

| Married/Long-term relationship | 0.41 ** | 0.21–0.81 |

| Living arrangements | ||

| Live alone | - | - |

| Live with other adults; no children | 12.11 * | 1.47–99.96 |

| Live with other adults and children < 18 yrs. | 7.25 | 0.88–59.65 |

| Live only with children < 18 yrs. | 3.92 | 0.50–30.93 |

| Work status | ||

| Casual or contract | - | - |

| Permanent | 0.65 | 0.37–1.14 |

| Behavioural characteristics | ||

| AUDIT score (alcohol consumption) (AC) | ||

| Low risk of harm | - | - |

| Moderate risk of harm | 0.20 ** | 0.06–0.60 |

| High risk of harm | 0.23 * | 0.07–0.78 |

| Likely dependence | 0.25 | 0.04–1.60 |

| DUDIT score (drug use/abuse) (DU) | ||

| Absence of drug-related problems | - | - |

| Possible drug-related problems | 0.03 ** | 0.003–0.04 |

| High level of drug dependency | 0.03 * | 0.002–0.51 |

| Hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|

| H1: Older construction workers are more likely to present with more depressive symptoms compared to younger construction workers in South Africa | Not supported |

| H2: In the South African construction industry, “Black” African workers are more likely to exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to individuals from “Other” ethnic backgrounds | Not supported |

| H3: In the South African construction industry, workers with higher levels of education are more likely to exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to their less educated counterparts | Partially supported |

| H5: Workers in the South African construction industry who live alone are more likely to exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to workers who cohabit with others | Not supported |

| H6: Construction workers on casual or temporary contracts in the South African construction industry are more likely to exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to their counterparts in permanent positions | Not supported |

| H8: In the South African construction industry, workers who score as at possible risk of drug-related problems or heavily dependent on drugs on validated tests are more likely to exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to workers who score as having no drug-related problems | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.P.; Bowen, P.; Edwards, P. Depressive Symptoms Among South African Construction Workers: Associations with Demographic, Social and Work-Related Factors, and Substance Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050694

Zhang RP, Bowen P, Edwards P. Depressive Symptoms Among South African Construction Workers: Associations with Demographic, Social and Work-Related Factors, and Substance Use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):694. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050694

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Rita Peihua, Paul Bowen, and Peter Edwards. 2025. "Depressive Symptoms Among South African Construction Workers: Associations with Demographic, Social and Work-Related Factors, and Substance Use" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050694

APA StyleZhang, R. P., Bowen, P., & Edwards, P. (2025). Depressive Symptoms Among South African Construction Workers: Associations with Demographic, Social and Work-Related Factors, and Substance Use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050694