Efficacy of a Brief Intervention to Improve the Levels of Nutrition and Physical Exercise Knowledge Among Primary School Learners in Tshwane, South Africa: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Instruments

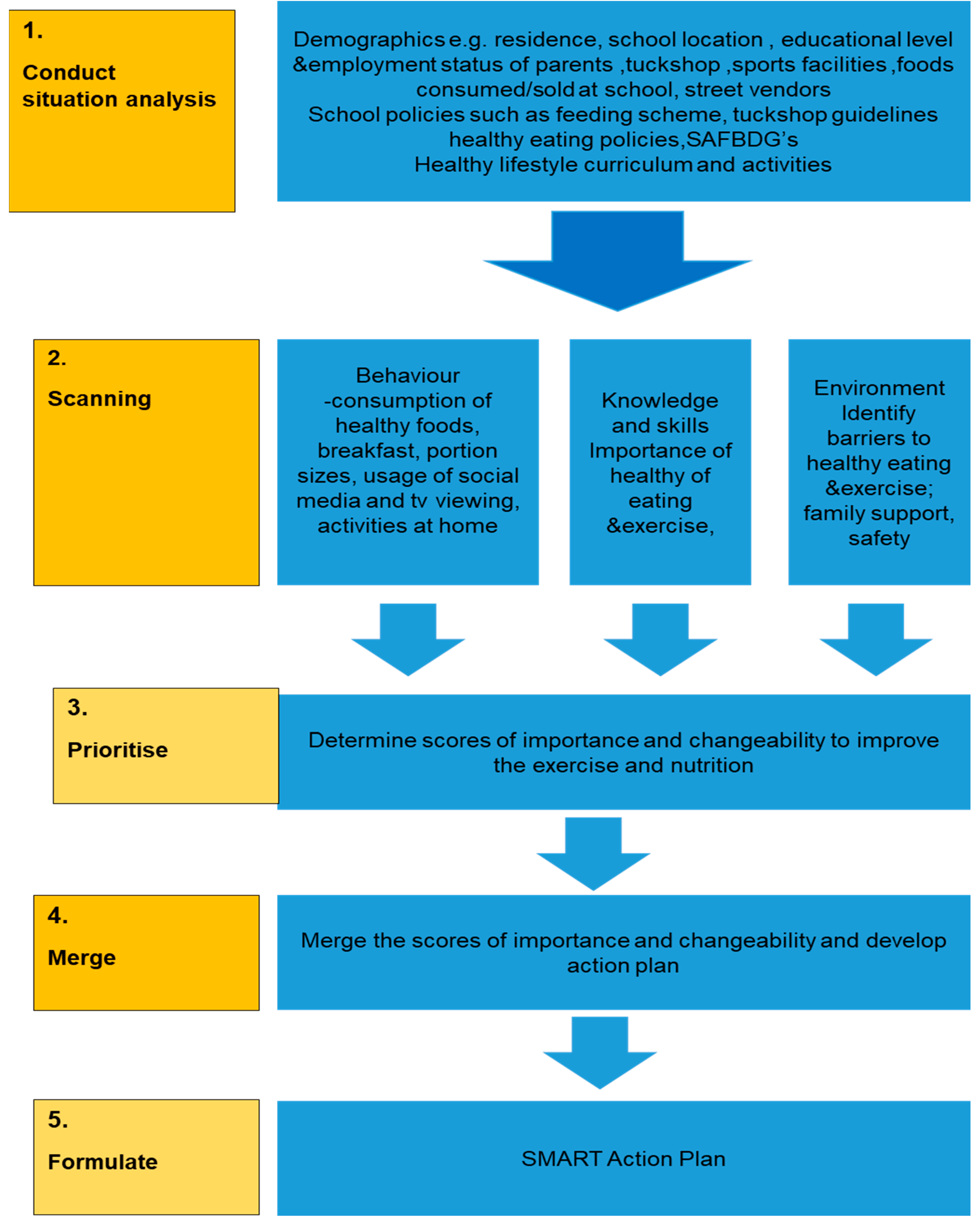

2.1.1. Step 1: Conduct Situational Analysis

2.1.2. Step 2: Scanning

2.1.3. Step 3: Prioritise

2.1.4. Step 4: Merge

2.1.5. Step 5: Formulate

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Brief Intervention

2.3.1. Nutrition and Exercise Education for School Learners

- -

- Educational presentations on the benefits of healthy eating; the importance of consuming fruits, vegetables, and water; and the dangers of consuming unhealthy foods, such as sweetened, fatty, and junk foods. Nutrition education was mainly based on the SAFBDGs;

- -

- For exercise: educational presentations focused on the benefits of exercise, exercise prescription, and injury prevention;

- -

- To further enhance knowledge, researchers designed posters and booklets, as well as used food models.

2.3.2. Nutrition and Exercise Materials

2.3.3. Nutrition and Exercise Education for Teachers

2.3.4. Training of Voluntary Food Handlers (VFHs)

- How to urgently substitute the menu in case of the delayed delivery of other food items on the menu;

- Food safety and hygiene;

- A demonstration on how to cook vegetables healthily;

- The use and implementation of the NSNP document.

2.3.5. Launch of Sports Day Events

2.3.6. Create Awareness About the NSNP Policy

- SA tuckshop guidelines: copies of the DOE tuckshop guidelines were distributed;

- The importance of establishing a vegetable garden and healthy eating.

2.3.7. Establishment of the Vegetable Garden

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.; Li, T. The impacts of multiple obesity-related interventions on quality of life in children and adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagbohun, A.; Orimadegun, A.; Yaria, J.; Falade, A. Obesity affects health-related quality of life in schools functioning among adolescents in Southwest of Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 24, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.G.C.D.; Godoy-Leite, M.; Penido, E.A.R.; Ribeiro, K.A.; da Gloria Rodrigues-Machado, M.; Rezende, B.A. Eating behaviour, quality of life and cardiovascular risk in obese and overweight children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Mozaffari, H.; Askari, M.; Azadbakht, L. Association between overweight/obesity with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, W.-W.; Zong, Q.-Q.; Zhang, J.-W.; An, F.-R.; Jackson, T.; Ungvari, G.S.; Xiang, Y.; Su, Y.Y.; D’Arcy, C.; Xiang, Y.T. Obesity increases the risk of depression in children and adolescents: Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 267, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M.; Carey, R. Behavior change techniques. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, N.; Trivedi, D.; Troop, N.A.; Chater, A.M. Are physical activity interventions for healthy inactive adults effective in promoting behavior change and maintenance, and which behavior change techniques are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C.; Kuhle, S.; Lu, C.; Purcell, M.; Schwartz, M.; Storey, K.; Veugelers, P.J. From “best practice” to “next practice”: The effectiveness of school-based health promotion in improving healthy eating and physical activity and preventing childhood obesity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laar, A.; Barnes, A.; Aryeetey, R.; Tandoh, A.; Bash, K.; Mensah, K.; Zotor, F.; Vandevijvere, S.; Holdsworth, M. Implementation of healthy food environment policies to prevent nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in Ghana: National experts’ assessment of government action. Food Policy 2020, 93, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, B.; Allahverdipour, H.; Shaghaghi, A.; Kousha, A.; Jannati, A. Challenges in developing health promoting schools’ project: Application of global traits in local realm. Health Promot. Perspect. 2014, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, K.E.; Kamaluddin, M.A.; Razak, A.Z.A.; Wahid, A.A.A. Building healthy eating habits in childhood: A study of the attitudes, knowledge and dietary habits of schoolchildren in Malaysia. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosettie, K.L.; Micha, R.; Cudhea, F.; Penalvo, J.L.; O’Flaherty, M.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Economos, C.D.; Whitsel, L.P.; Mozaffarian, D. Comparative risk assessment of school food environment policies and childhood diets, childhood obesity, and future cardiometabolic mortality in the United States. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cohen, J.F.W.; Maroney, M.; Cudhea, F.; Hill, A.; Schwartz, C.; Lurie, P.; Mozaffarian, D. Evaluation of health and economic effects of United States school meal standards consistent with the 2020–2025 dietary guidelines for Americans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, E.; Gottesman, K.; Hamlett, P.; Mattar, L.; Robinson, J.; Tovar, A.; Rozga, M. Impact of nutrition and physical activity interventions provided by nutrition and exercise practitioners for the adult general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Education DoB (Ed.) National School Nutrition Programme; Department of Basic Education: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Health Do (Ed.) Strategy for Prevention and Control of Obesity in South Africa, 2015–2020; Republic of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Policy—National School Nutrition Programme—Guidelines for Tuckshop Operators South Africa. 2014. Available online: https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/policy-documents/guideline/ZAF-AD-30-01-GUIDELINE-2014-eng-NSNP-GuideLines-for-Tuck-Shop-Operators.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Phetla, M.C.; Skaal, L. Scanning for Obesogenicity of Primary School Environments in Tshwane, Gauteng, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samdal, G.B.; Eide, G.E.; Barth, T.; Williams, G.; Meland, E. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drimie, S.; van den Bold, M.; du Plessis, L.; Casu, L. Stories of Challenge in South Africa: Changes in the enabling environment for nutrition among young children (1994–2021). Food Secur. 2023, 15, 1629–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogre, V.; Scherpbier, A.J.; Stevens, F.; Aryee, P.; Cherry, M.G.; Dornan, T. Realist synthesis of educational interventions to improve nutrition care competencies and delivery by doctors and other healthcare professionals. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, J.D.; Jepson, R.; Frank, J.; Geddes, R. Obesity prevention in Scotland: A policy analysis using the ANGELO framework. Obes. Facts 2015, 8, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giguère, A.; Zomahoun, H.T.V.; Carmichael, P.H.; Uwizeye, C.B.; Légaré, F.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Gagnon, M.P.; Auguste, D.U.; Massougbodji, J. Printed educational materials: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, Cd004398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanica, N.; Catak, A.; Mujezinovic, A.; Begagic, S.; Galijašević, K.; Oruč, M. The Effectiveness of Leaflets and Posters as a Health Education Method. Mater. Socio-Med. 2020, 32, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.; Theobald, C. Development and Evaluation of Food and Nutrition Teaching Kits for Teachers of Primary Schoolchildren; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.; Goffe, L.; Brown, T.; Lake, A.A.; Summerbell, C.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Adamson, A.J. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1–4 (2008–12). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, F.M.M.; de Paula, J.S.; Mialhe, F.L. Teachers’ views about barriers in implement oral health education for school children: A qualitative study. Braz. Dent. Sci. 2014, 17, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaRosa, D.A.; Skeff, K.; Friedland, J.A.; Coburn, M.; Cox, S.; Pollart, S.; O’connell, M.; Smith, S. Barriers to effective teaching. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayasari, E.; Hayu, R.E.; Permanasari, I. Education Media Videos and Posters on Healthy Snacks Behavior In Elementary Schools Students. STRADA J. Ilm. Kesehat. 2020, 9, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, M.; Husson, H.; DeCorby, K.; LaRocca, R.L. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD007651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Sancho, Á.; Sánchez-Calvo, M. Influence of knowledge area on the use of digital tools during the COVID-19 pandemic among Latin American professors. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur-Nyarko, E.; Agyei, D.D.; Armah, J.K. Digitizing distance learning materials: Measuring students’ readiness and intended challenges. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 2987–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.N.; Sachchithananthan, S.; Gamage, P.S.A.; Peiris, R.; Wickramasinghe, V.P.; Somasundaram, N. Effectiveness and acceptability of a novel school-based healthy eating program among primary school children in urban Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runo, W.S.; Kiara, K.; Mandela, R. Influence of Nutrition Knowledge on Healthy Food Choices among Pupils in Nyeri County, Kenya. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Annan, R.A.; Apprey, C.; Agyemang, G.O.; Tuekpe, D.M.; Asamoah-Boakye, O.; Okonogi, S.; Yamauchi, T.; Sakurai, T. Nutrition education improves knowledge and BMI-for-age in Ghanaian school-aged children. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambuko, C.; Gericke, G.; Muchiri, J. Effects of school-based nutrition education on nutrition knowledge, self-efficacy and food choice intentions of learners from two primary schools in resource limited settings of Pretoria. J. Consum. Sci. 2020, 48, 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, P.; Hasni, A. Interest, motivation and attitude towards science and technology at K-12 levels: A systematic review of 12 years of educational research. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2014, 50, 85–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Hall, K. Physical education or playtime: Which is more effective at promoting physical activity in primary school children? BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, V.P.; Stodden, D.F.; Rodrigues, L.P. Effectiveness of physical education to promote motor competence in primary school children. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2017, 22, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlawski, E.A. Peer learning in first grade: Do children communicate with each other during learning activities? J. Integr. Innov. Humanit. 2021, 1, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Boys = (n%) | Girls = (n%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | <11 years | 27 (63) | 32 (74) | 0.245 |

| >11 years | 16 (37) | 11 (26) | ||

| Learners stay | Parents | 36 (84) | 33 (77) | 0.430 |

| Others | 7 (16) | 10 (23) | ||

| Carries lunchbox | Yes | 35 (81) | 32 (74) | 0.143 |

| No | 8 (19) | 11 (26) | ||

| Eats via a feeding scheme | Yes | 32 (74) | 33 (77) | 0.881 |

| No | 11 (26) | 10 (23) | ||

| Carries pocket money | Yes | 33 (77) | 28 (65) | 0.650 |

| No | 10 (33) | 15 (35) | ||

| Mode of transport | Car | 21 (49) | 18 (42) | 0.650 |

| Walk | 22 (51) | 25 (58) | ||

| BMI | Obese | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 0.151 |

| Overweight | 3 (7) | 1 (2) | ||

| Normal | 17 (40) | 25 (58) | ||

| Thinness | 22 (51) | 14 (33) | ||

| Statement Related to Posters—Nutrition Booklet and Nutrition Education Used in the Implementation of Nutrition Programme | Yes |

|---|---|

| Posters (n = 86) | |

| Did you see posters about nutrition and exercise? | 100% |

| Did you read what is written on the posters? | 100% |

| Did you understand the information on the posters? | 100% |

| Did the posters improve your knowledge of nutrition and exercise? | 100% |

| Nutrition booklet (n = 86) | |

| Did you receive the nutrition and exercise information booklet? | 100% |

| Did you read what is written in the nutrition and exercise booklet? | 100% |

| Did you understand the information in the nutrition and exercise information booklet? | 100% |

| Did the information in the booklet improve your nutrition and exercise knowledge? | 100% |

| Nutrition education (n = 86) | |

| Did you attend nutrition and exercise education classes? | 100% |

| Did you understand the information presented during nutrition and exercise education? | 100% |

| Did nutrition and exercise education improve your knowledge? | 100% |

| Did you start eating healthy foods daily? | 100% |

| Are you willing to exercise 3 times a week for 60 min? | 100% |

| Sports Day (n = 86) | |

| Did you enjoy the activities of the sports day? | 100% |

| Did you benefit from sports day? | 100% |

| I have started to exercise regularly. | 100% |

| Mean | Std Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | Significance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | t | df | One-Sided p | Two-Sided p | ||||

| Pair 1 Nutrition knowledge (pretest) Nutrition knowledge (post-test) | −5.34884 | 3.31047 | 0.35698 | −6.05860 | −4.63907 | −14,984 | 85 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pair 2 Exercise knowledge (pretest) Exercise knowledge (post-test) | −2.52326 | 1.69238 | 0.18249 | −2.88610 | −2.16041 | −13,826 | 85 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phetla, M.C.; Skaal, L. Efficacy of a Brief Intervention to Improve the Levels of Nutrition and Physical Exercise Knowledge Among Primary School Learners in Tshwane, South Africa: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121592

Phetla MC, Skaal L. Efficacy of a Brief Intervention to Improve the Levels of Nutrition and Physical Exercise Knowledge Among Primary School Learners in Tshwane, South Africa: A Quasi-Experimental Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(12):1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121592

Chicago/Turabian StylePhetla, Morentho Cornelia, and Linda Skaal. 2024. "Efficacy of a Brief Intervention to Improve the Levels of Nutrition and Physical Exercise Knowledge Among Primary School Learners in Tshwane, South Africa: A Quasi-Experimental Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 12: 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121592

APA StylePhetla, M. C., & Skaal, L. (2024). Efficacy of a Brief Intervention to Improve the Levels of Nutrition and Physical Exercise Knowledge Among Primary School Learners in Tshwane, South Africa: A Quasi-Experimental Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(12), 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121592