Evaluation of Integrative Community Therapy with Domestic Violence Survivors in Quito, Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Description of Integrative Community Therapy

1.2. Evidence of ICT Effectiveness

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Health

2.2.2. Self-Esteem

2.2.3. Social Support

2.2.4. Resilience

2.2.5. Dating Violence Attitudes

2.2.6. Participant Feedback

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison between Groups

3.2. Quantitative Results

3.3. Qualitative Results

3.3.1. Theme 1: Changes in the Violent Relationship

“I do not have a current relationship with my aggressor, neither verbal and much less physical. Since we finished, I have focused on my space, my well-being and getting out of all of that, completely removing him from my life and starting to live from scratch.”

“I have imposed limits, I recognize his victimhood so that he sometimes recognizes that he needs help, I feel more sure of myself, with the strength that if there are no changes, if I can get out of there, I no longer feel alone.”

“Until now, I always take a song from Lu that said “I sway, but I don’t fall. I sway, but I don’t fall.” So every time I have a difficulty, I remember that and I know that I can sway, but I’m not going to fall. And well, this circle of help also came at a very difficult time for me, very difficult, with my aggressor. We were closing an important issue and I was too scared to talk to him. It scared me a lot. But this helped me understand, because in each circle we talk a little about what I had already experienced, remember that there are difficult things and I will overcome them. I knew how to handle it and I’m still here, and that also helped my self-esteem knowing that I can make my decisions, for myself, without fear of anyone.”

3.3.2. Theme 2: Psychological and Emotional Changes

“It has helped me a lot to understand self-love, the many ways in which I can get ahead and that this reality is more common than normal but that I am not alone and that I can trust people. I can help and I can help myself, so that this never happens to me again and I can finally be happy with my new life loving myself.”

“I believe that this workshop that we have followed and of which I have been a part has helped me a lot to embark on a path of many things. I have realized mistakes that I have made and that, more than anything, I have lacked self-love. Realize that I have to learn to forgive myself. If I’ve made mistakes, then that’s life, right? In other words, the important thing is to move forward and improve as human beings. So, I take all that with me and it has served me a lot, it has motivated me a lot to see life differently, with more optimism, being more positive. That has helped me.”

3.3.3. Theme 3: Changes in Feelings of Social Support

“They have helped me a lot, many times I blamed myself too much and thought I was the only one who had suffered. After listening to them I feel stronger, empowered and more self-esteem (which I didn’t have much of before).”

“I felt that I was no longer alone, I was able to talk about topics that I did not talk about with anyone, they listened to me and supported me, I also felt peace and singing the songs or doing exercises outside during my daily life prolonged the effect of peace and company.”

“I think I learned a lot because my fear was always speaking and telling my experience and feeling judged. Because that is what happened to me at the beginning when I spoke and told what had happened to me. People usually always said to me, “But why didn’t you speak up?” But when I had the opportunity to talk about it here, no one said it that way, instead they understood it. They understand the experiences we live, each one of us is healing at their own pace. I know that I lack many things to let go of, but it is the first time that I spoke about it in a group with other women where I actually felt loved from a distance. It was also very nice to experience this circle of support and listening, which is something that I had not experienced and had not had within reach….”

3.3.4. Theme 4: Changes for the Future

“I really liked the experience, and I have also talked with my friends who have been through the same thing. It is necessary to have these spaces to feel safe, with empathy. There are many times that we don’t talk to other people because they can’t understand us because they haven’t been through the same thing. I feel that this is very important in these groups. We know how we feel. We empathize with each other because we’ve been through it. Only we can understand everything we’ve been through.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. Encuesta Nacional de Relaciones Familiares y Violencia de Genero Contra las Mujeres; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos: Quito, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Organización de los Estados Americanos.Convención Interamericana para Prevenir, Sancionar y Erradicar la Violencia contra la Mujer. Available online: https://www.oas.org/juridico/spanish/tratados/a-61.html (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Constitución de la República del Ecuador. Available online: https://www.asambleanacional.gob.ec/sites/default/files/documents/old/constitucion_de_bolsillo.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Declaración Sobre el Femicidio. Available online: https://www.oas.org/es/mesecvi/docs/declaracionfemicidio-es.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Código Orgánico de Organización Territorial, Autonomía y Descentralización. Available online: https://www.gob.ec/regulaciones/codigo-organico-organizacion-territorialcootad (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Código Orgánico Integral Penal. Available online: http://biblioteca.defensoria.gob.ec/handle/37000/3427 (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Organización de los Estados Americanos. Declaración sobre la Violencia y el acoso Políticos Contra las Mujeres. Available online: https://www.oas.org/es/mesecvi/docs/declaracionviolenciapolitica-es.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Corporación Utopía. Fortalecimiento de las Comisarías de la Mujer y la Familia: Sistematización de las Comisarías de la Mujer y la Familia; Centro Ecuatoriano para la Promoción y Acción de la Mujer: Quito, Ecuador, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cuvi Sánchez, M. Violencia Contra las Mujeres: La Ruta Crítica en Ecuador; OPS/OMS: Quito, Ecuador, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, C.; Carrillo, P. Los Lenguajes de la Impunidad: Informe de Investigación Delitos Sexuales y Administración de Justicia; Centro Ecuatoriano para la Promoción y Acción de la Mujer: Quito, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Valencia, L.; Galindo, D. Coloniality and psychology: The uprooting of knowledge. Rev. Polis Psique 2019, 9, 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, A. Terapia Comunitária Integrativa Paso a Paso; Gráfica LCR: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira Filha, M.d.O.; Lazarte, R.; Barreto, A.d.P. Impacto e tendências do uso da Terapia Comunitária Integrativa na produção de cuidados em saúde mental. Rev. Eletrônica Enferm. Órgão Fac. Enferm. Univ. Fed. Goiás 2015, 17, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugon, N. La TCI & la Antropologia Cultural; Taller de Terapia Comunitaria Integrativa: Tumbaco, Ecuador, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, L.; Dewar, J. Creative arts, culture, and healing: Building an evidence base. Primatisiwin A J. Aborig. Indig. Community Health 2010, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeneme, S.; Eni, G.; Ezuma, A.; Fortwengel, G. Roads to health in developing countries: Understanding the intersection of culture and healing. Curr. Ther. Res. 2017, 86, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, A.; Grandesso, M. Community therapy: A participatory response to psychic misery. Int. J. Narrat. Ther. Community Work 2010, 2010, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P.; Faundez, A. Learning to Question: A Pedagogy of Liberation; The World Council of Churches: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barranquero Carretero, A.; Sáez Baeza, C. Comunicación y buen vivir. La crítica descolonial y ecológica a la comunicación para el desarrollo y el cambio social. Palabra-Clave 2014, 18, 41–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarte, R. Terapia Comunitaria Reflexions. 2011. Available online: https://docplayer.es/21015728-Terapia-comunitaria-reflexiones-rolando-lazarte.html (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Watzlawick, P.; Beavin, J.B.; Jackson, D.D. Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies, and Paradoxes; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D. Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901–1972) General Systems Theory. In The Science of Synthesis; Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems Theory; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2003; pp. 103–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Campaña Medina, E.; Pereyra, E.; Ruedas vinculates. Nueva tecnologia social al servicio de la gente. In Prácticas Pedagógicas Para el Fomento de la Inter-Culturalidad en el Contexto Universitario: La Experiencia de la Universidad Estatal Amazónica Enconvenio con la Universidad de Málaga; Leiva Olivencia, J.J., Gutiérrez Valerio, R., Eds.; Universidad Estatal Amazonica: Puyo, Ecuador, 2018; pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma; Penguin Publishing Group: New York City, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tummala-Narra, P. Conceptualizing trauma and resilience across diverse contexts: A multicultural perspective. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2007, 14, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.; Hamby, S.; Banyard, V. The resilience portfolio model: Understanding healthy adaptation in victims of violence. Psychol. Violence 2015, 5, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filha, M.D.O.F.; Dias, M.D.; de Andrade, F.B.; de Lima, É.A.R.; Ribeiro, F.F.; Silva, M.D.S.S.D. A terapia comunitária como estratégia de promoção à saúde mental: O caminho para o empoderamento. Rev. Eletrônica Enferm. Órgão Fac. Enferm. Univ. Fed. Goiás 2009, 11, 964–970. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães Lemes, A.; Marcelino da Rocha, E.; Ferreira do Nascimento, V.; Jacinto Volpato, R.; Sousa Oliveira Almeida, M.A.; Franco, S.E.d.J.; Bauer, T.X.; Villar Luis, M.A. Benefits of Integrative Community Therapy revealed by psychoactive drug users. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.A.P.; Dias, M.D.; Miranda, F.A.N.; Ferreira Filha, M.d.O. Contributions by Integrative Community Therapy to users of Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS) and family members: Thematic oral history. Cad. Saúde Pública 2013, 29, 2028–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, I.A.; Sá, A.N.P.; Braga, L.A.V.; Ferreira Filha, M.d.O.; Dias, M.D. Community integrative therapy: Situations of emotional suffering and patients’ coping strategies. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2013, 34, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jatai, J.M.; Silva, L.M.S. Enfermagem e a implantação da Terapia Comunitária Integrativa na Estratégia Saúde da Família: Relato de experiência. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2012, 65, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, E.B.; Cordeiro, R.C.; Pimentel Costa, L.d.F.; Guerra, C.d.S.; Ferreira Filha, M.d.O.; Dias, M.D. Pesquisas brasileiras sobre terapia comunitária integrativa. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Saúde 2013, 15, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, V.R.; Dias, M.D.; Ferreira Filha, M.d.O. Contribuições da terapia comunitária para o enfrentamento das inquietações de gestantes. Rev. Eletrônica Enferm. Órgão Fac. Enferm. Univ. Fed. Goiás 2007, 9, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, S.G.; Ferreira Filha, M.d.O.; Paredes Moreira, M.A.S.; Simpson, C.A.; Rangel Tura, L.F.; Silva, A.O. Social representations of integrative community therapy by the elderly. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2017, 38, e55067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zem Igeski, T.P.; Silva, L.P.; Silva, D.B.; Silva, M.Z. Análise da efetividade da Terapia Comunitária Integrativa na saúde biopsicossocial de diferentes populações: Uma revisão integrativa. Temas Educ. Saúde 2020, 16, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães Lemes, A.; Ferreira do Nascimento, V.; Marcelino da Rocha, E.; Santos da Silva, L.; Sousa Oliveira Almeida, M.A.; Jacinto Volpato, R.; Villar Luis, M.A. A terapia comunitária integrativa no cuidado em saúde mental: Revisão integrativa. Rev. Bras. Promoção Saúde 2020, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.I.; Felipe, A.O.B.; Moreira, D.d.S. Integrative Community Therapy—Interventive strategies in the reduction of depression symptoms in adolescents: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1426–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, C.; Dalley, T. The Handbook of Art Therapy, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCart, M.R.; Smith, D.W.; Sawyer, G.K. Help seeking among victims of crime: A review of the empirical literature. J. Trauma. Stress 2010, 23, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaca-Ferrer, R.; Ferro-García, R.; Valero-Aguayo, L. Efficacy of a group intervention program with women victims of gender violence in the framework of contextual therapies. An. Psicol. 2020, 36, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.P.; Williams, P. A User’s Guide to the General Health Questionnaire; NFER-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-López, M.D.P.; Dresch, V. The 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): Reliability, external validity and factor structure in the Spanish population. Psicothema 2008, 20, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, M.; Arinero, M.; Soberon, C. Analysis of effectiveness of individual and group trauma-focused interventions for female victims of intimate partner violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, G.; Lopez-Nunez, C.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Barrios-Fernandez, S.; Rojo-Ramos, J.; Adsuar, J.C.; Collado-Mateo, D. A multicomponent program to improve self-concept and self-esteem among intimate partner violence victims: A study protocol for a randomized controlled pilot trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpana, H.M.; Lang, J.J.; Yurkowski, K. Validation of a brief version of the Social Provisions Scale using Canadian national survey data. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pract. 2019, 39, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Russell, D. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In Advances in Personal Relationships; Jones, W.H., Perlman, D., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1987; Volume 1, pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, L.E.; Manriquez Prado, A.K.; Santos Malavé, G.F.; Vélez, J.C.; Gillibrand Esquinazi, R.W.; Sanchez, S.E.; Zhong, Q.-Y.; Gelaye, B.; Williams, M.A. Construct validity and factor structure of a spanish-language social support questionnaire during early pregnancy. Int. J. Women’s Health 2018, 10, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rey, R.; Alonso-Tapia, J.; Hernansaiz-Garrido, H. Reliability and validity of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) spanish version. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, e101–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández González, L. Calvete Zumalde, Esther, Orue Sola, Izaskun. The Acceptance of Dating Violence scale (ADV): Psychometric properties of the Spanish version. Psicothema 2017, 29, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelazeem, B.; Abbas, K.S.; Amin, M.A.; El-Shahat, N.A.; Malik, B.; Kalantary, A.; Eltobgy, M. The effectiveness of incentives for research participation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrs Fuchsel, C.L.; Hysjulien, B. Exploring a Domestic Violence Intervention Curriculum for Immigrant Mexican Women in a Group Setting: A Pilot Study. Soc. Work Groups 2013, 36, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey-Bass: San Franciso, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Larance, L.Y.; Porter, M.L. Observations from practice: Support group membership as a process of social capital formation among female survivors of domestic violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, Z.E.; Morrison, S.D.; Norsigian, J.; Rosero, E. Reaching Latinas with Our Bodies, Ourselves and the Guia de Capacitacion para Promotoras de Salud: Health education for social change. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2012, 57, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrata, J.V.; Hernandez-Martinez, M.; Macias, R.L. Self-empowerment of immigrant Latina survivors of domestic violence: A promotora model of community leadership. Hisp. Health Care Int. 2016, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, L.A.; Smyth, K.F. A call for a social network-oriented approach to services for survivors of intimate partner violence. Psychol. Violence 2011, 1, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 64) | ||

| 19–29 | 33 | 51.6% |

| 30–39 | 21 | 32.8% |

| 40+ | 10 | 15.6% |

| Ethnic Identity (n = 86) | ||

| Indigenous or indigenous nationality | 1 | 1.2% |

| Montubia | 2 | 2.3% |

| Mestiza | 80 | 93% |

| White | 3 | 3.5% |

| Civil Status (n = 86) | ||

| Married | 3 | 3.5% |

| Civil union | 2 | 2.3% |

| In a relationship | 21 | 24.4% |

| Single | 34 | 39.5% |

| Separated | 13 | 15.1% |

| Divorced | 13 | 15.1% |

| Level of education (n = 86) | ||

| Completed primary school | 1 | 1.2% |

| Completed secondary school | 16 | 18.6% |

| Did not complete university or technical school | 18 | 20.9% |

| Completed university or technical school | 34 | 39.5% |

| Did not complete postgraduate degree | 3 | 3.4% |

| Postgraduate degree completed | 6 | 7.0% |

| Other (including currently in school) | 8 | 9.3% |

| Employment in the previous week (n = 86) | ||

| I was a student | 21 | 24.4% |

| I worked | 34 | 39.5% |

| I didn’t work but I have a job | 2 | 2.3% |

| I was looking for work for the first time | 1 | 1.2% |

| I was looking for work that I did previously | 12 | 14.0% |

| I did domestic labor | 7 | 8.1% |

| I have a physical or mental limitation that does not allow me to work | 3 | 3.5% |

| I did not work | 6 | 7.0% |

| Number of violent relationships (n = 86) | ||

| 1 | 36 | 41.9% |

| 2 | 30 | 34.9% |

| 3 to 5 | 17 | 19.8% |

| More than 5 | 3 | 3.5% |

| The most recent relationship that included violence (n = 86) | ||

| Casual dating partner | 2 | 2.3% |

| Steady partner | 45 | 52.3% |

| Partner I was living with | 23 | 26.7% |

| Husband | 16 | 18.6% |

| Type of violence in the last relationship (n = 87) | ||

| Physical | 64 | 73.6% |

| Sexual | 47 | 54% |

| Reproductive | 13 | 14.9% |

| Psychological or emotional | 87 | 100% |

| Economic | 43 | 49.4% |

| Stalking | 46 | 52.9% |

| How long was your last relationship that included violence (n = 87) | ||

| Less than a year | 13 | 14.9% |

| 1–2 years | 23 | 26.4% |

| 3–5 years | 26 | 29.8% |

| 6–9 years | 14 | 16% |

| 10+ years | 11 | 12.6% |

| When did your last violent relationship end (n = 87) | ||

| Currently in the relationship | 1 | 1.1% |

| Less than six months ago | 12 | 13.8% |

| 6 to 11 months ago | 8 | 9.2% |

| 1–2 years ago | 30 | 34.5% |

| 3–5 years ago | 20 | 22.9% |

| 6+ years ago | 16 | 18.3% |

| Services used to help with partner violence (n = 82) | ||

| Social work | 4 | 4.9% |

| Psychologist or mental health professional | 51 | 62.2% |

| Attorney or public defender | 2 | 2.4% |

| Group therapy | 9 | 11% |

| Judicial system | 8 | 9.8% |

| Civil rights protection | 1 | 1.2% |

| Police | 7 | 8.5% |

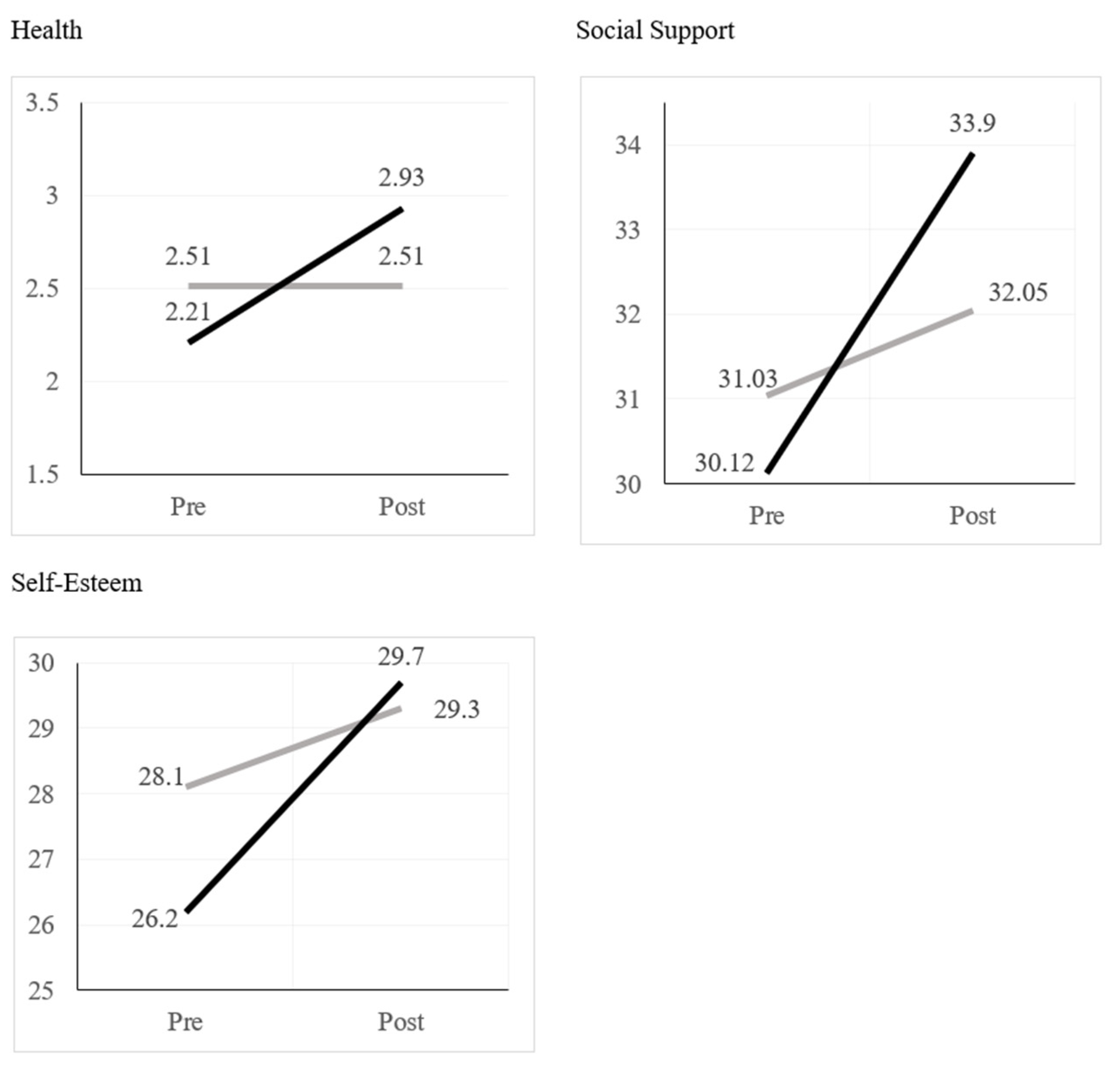

| Pre | Post | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dating Violence Attitudes | Intervention | 1.11 | 1.01 | 3.04 | 0.09 |

| Comparison | 1.21 | 1.25 | |||

| Resilience | Intervention | 16.08 | 18.04 | 0.25 | 0.62 |

| Comparison | 16.21 | 17.61 | |||

| Health | Intervention | 2.21 | 2.94 | 19.04 | <0.001 |

| Comparison | 2.50 | 2.51 | |||

| Social Support | Intervention | 30.13 | 33.90 | 8.10 | 0.01 |

| Comparison | 31.03 | 32.05 | |||

| Self-esteem | Intervention | 26.20 | 29.65 | 3.98 | 0.05 |

| Comparison | 28.08 | 29.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sabina, C.; Perez-Figueroa, D.; Reyes, L.; Campaña Medina, E.; Pereira de Souza, E.; Markovits, L.; Oña Jacho, A.C.; Rojas Bohorquez, G.K. Evaluation of Integrative Community Therapy with Domestic Violence Survivors in Quito, Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085492

Sabina C, Perez-Figueroa D, Reyes L, Campaña Medina E, Pereira de Souza E, Markovits L, Oña Jacho AC, Rojas Bohorquez GK. Evaluation of Integrative Community Therapy with Domestic Violence Survivors in Quito, Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(8):5492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085492

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabina, Chiara, Diego Perez-Figueroa, Laurent Reyes, Eduardo Campaña Medina, Eluzinete Pereira de Souza, Lisa Markovits, Andrea Carolina Oña Jacho, and Gissel Katherine Rojas Bohorquez. 2023. "Evaluation of Integrative Community Therapy with Domestic Violence Survivors in Quito, Ecuador" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 8: 5492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085492

APA StyleSabina, C., Perez-Figueroa, D., Reyes, L., Campaña Medina, E., Pereira de Souza, E., Markovits, L., Oña Jacho, A. C., & Rojas Bohorquez, G. K. (2023). Evaluation of Integrative Community Therapy with Domestic Violence Survivors in Quito, Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(8), 5492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085492