Associations between Socioeconomic Status and Psychological Distress: An Analysis of Disaggregated Latinx Subgroups Using Data from the National Health Interview Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mental Health and Latinx Subgroups in the US

1.2. Sociodemographic Factors Influencing Mental Health among Latinx Subgroups

1.3. Socioeconomic Status as a Fundamental Cause of Mental Health Disparities

1.4. Specific Aims

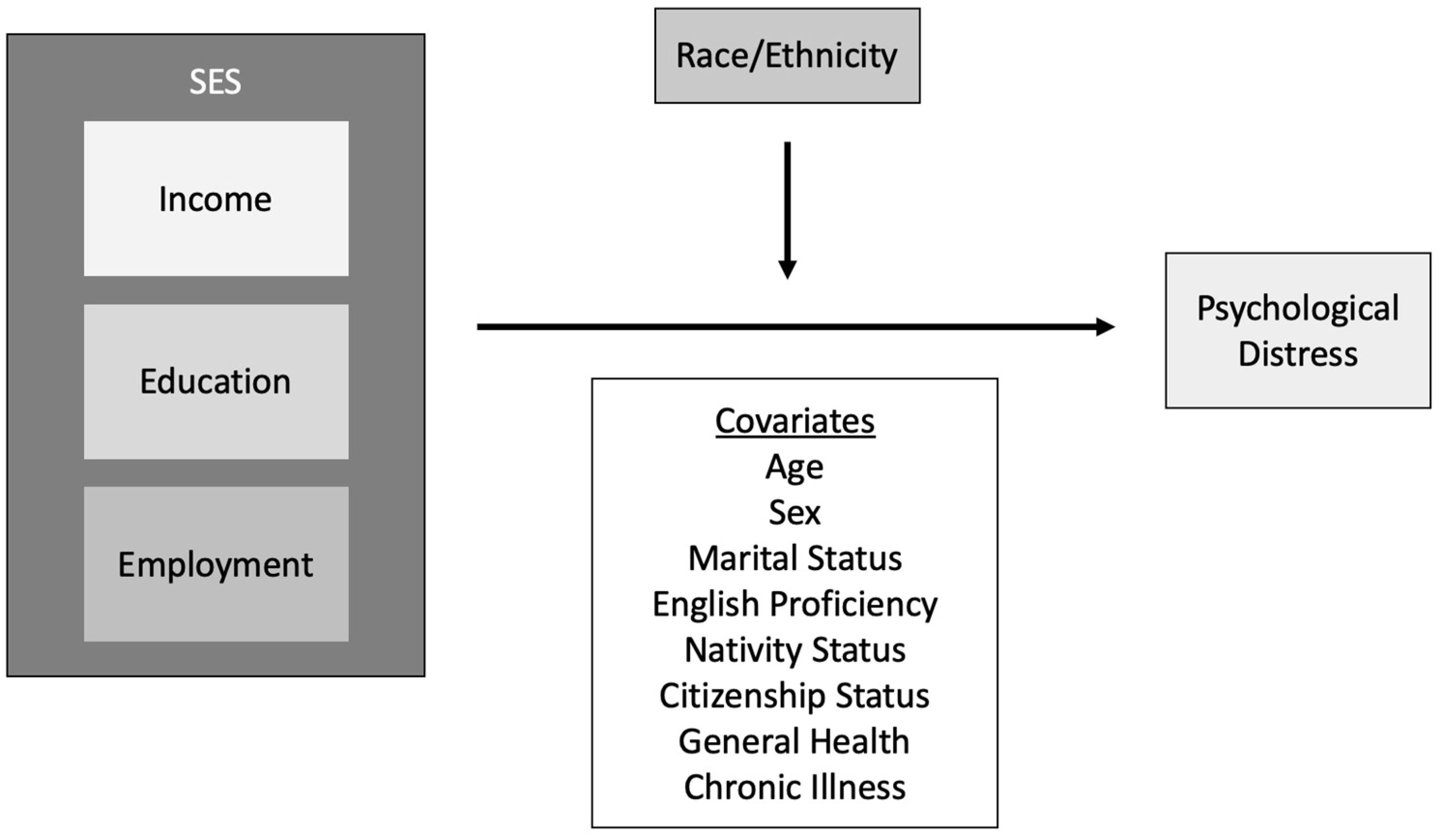

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

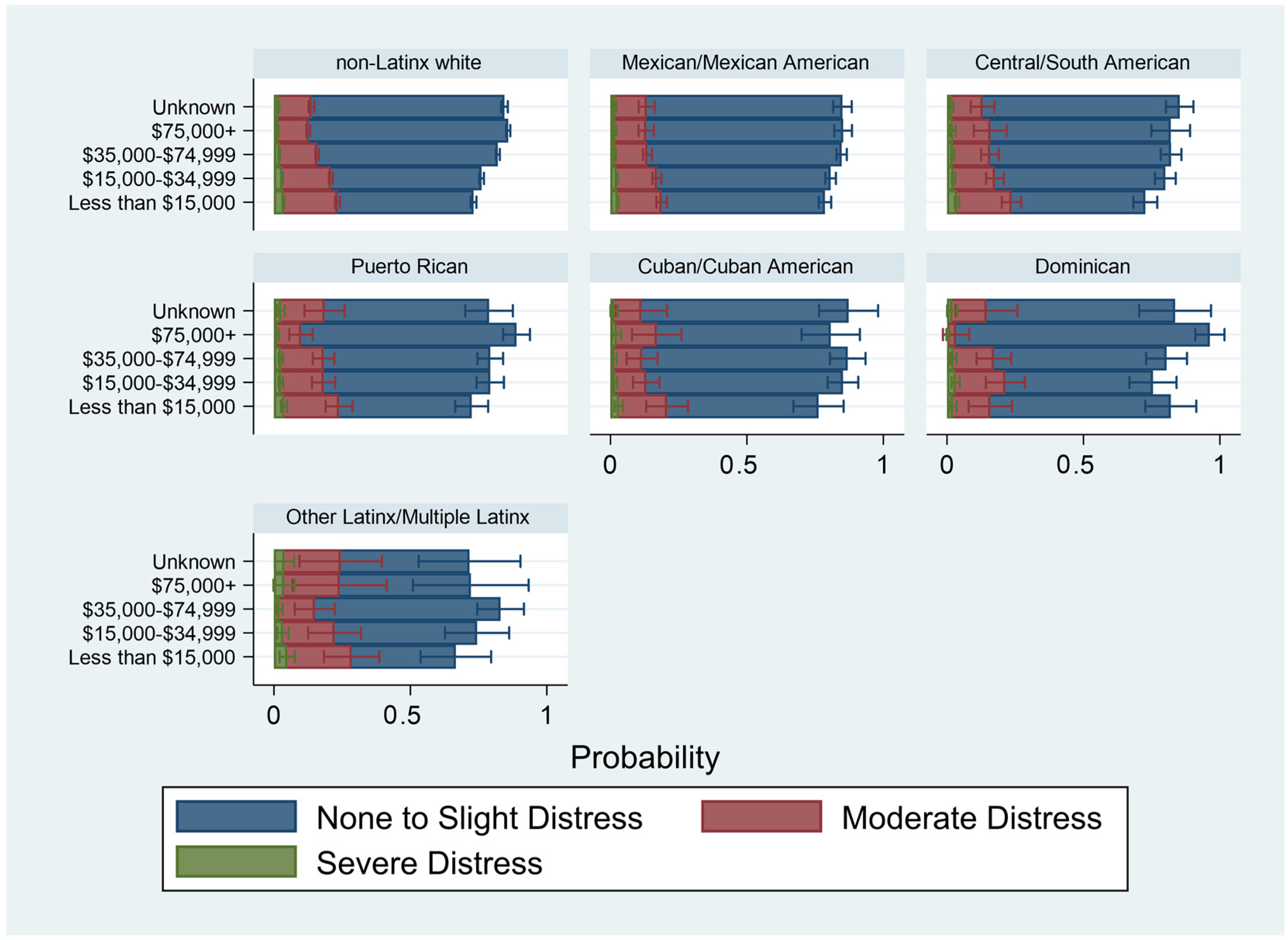

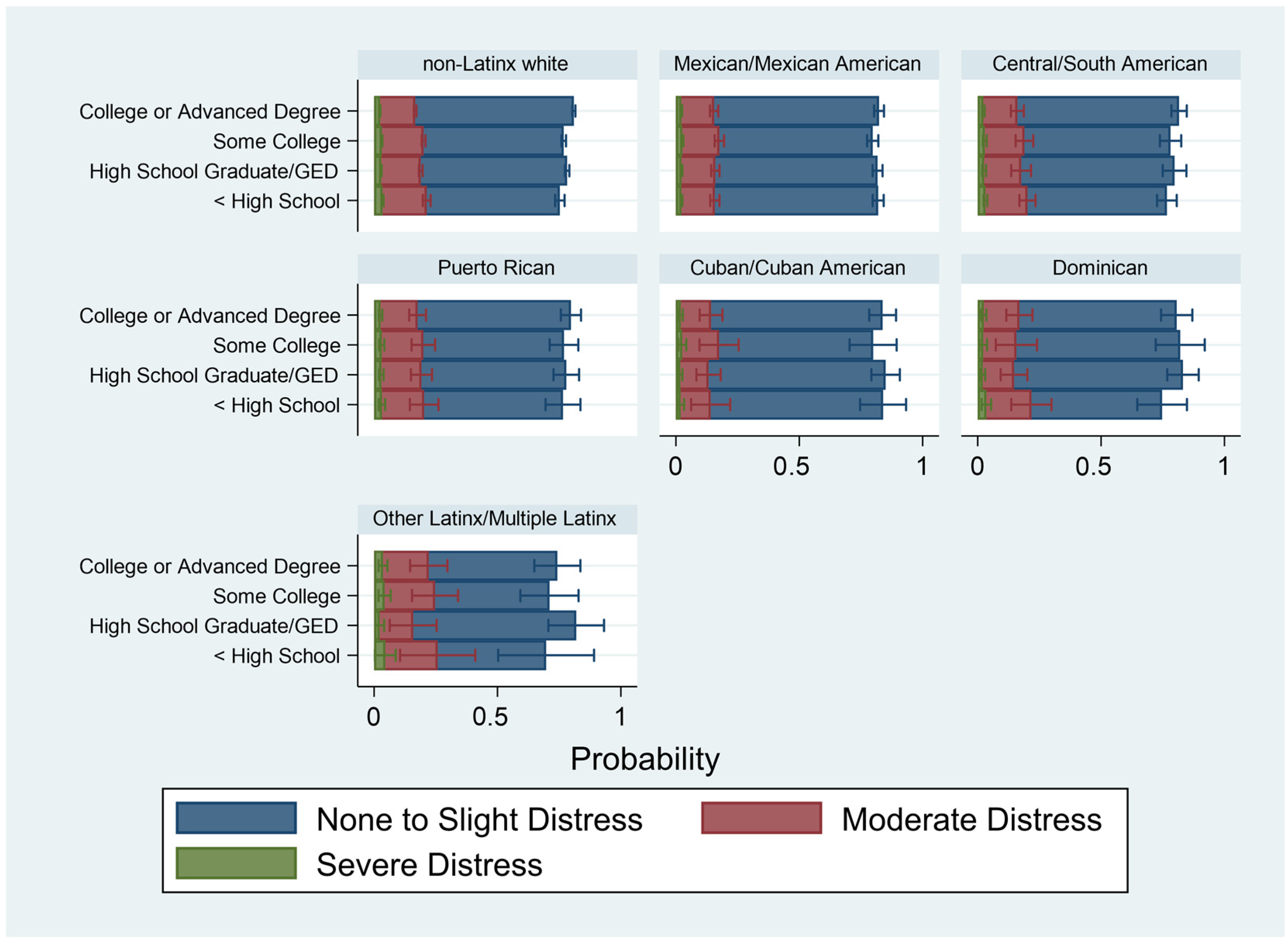

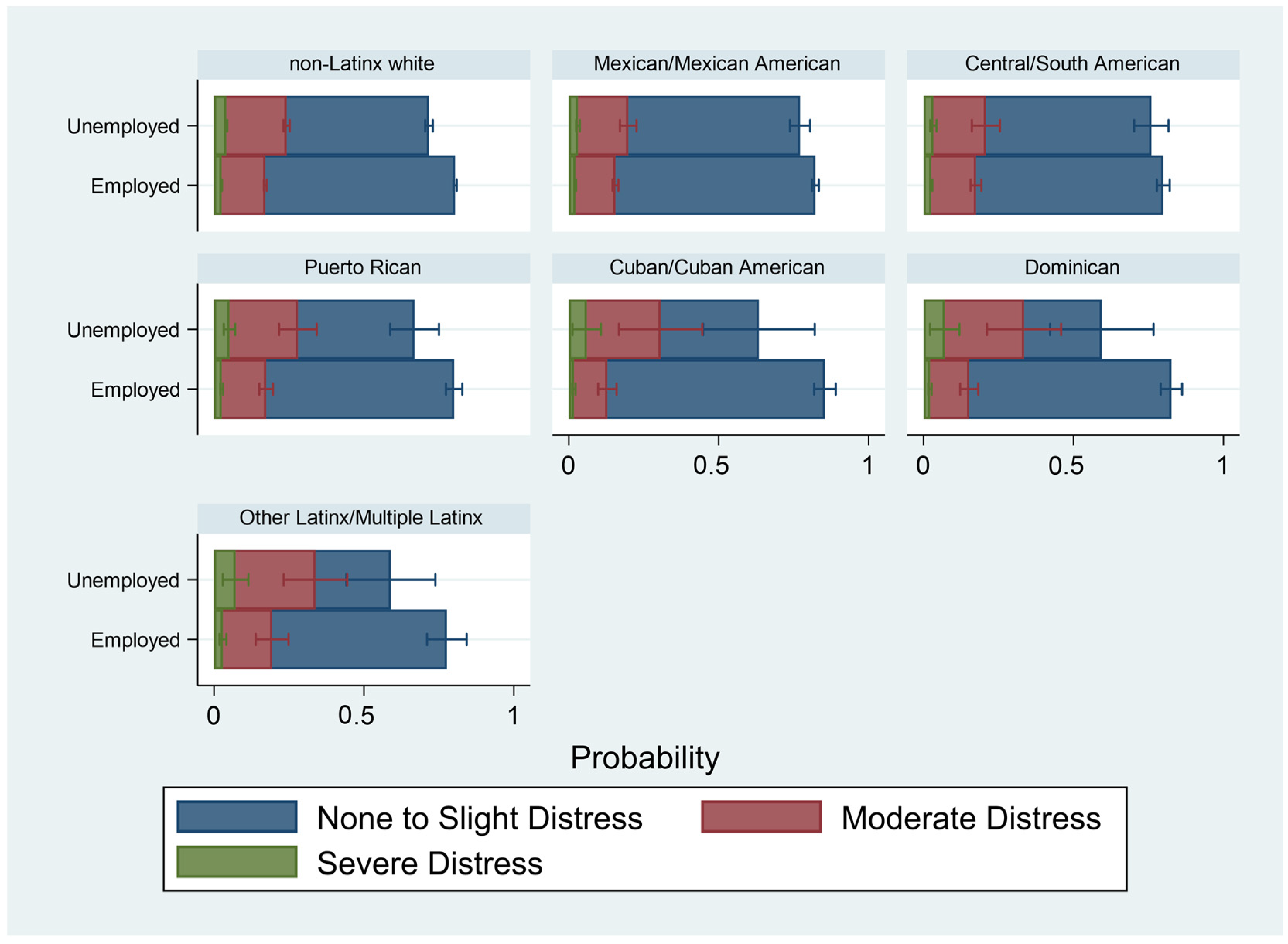

3.2. Associations between Income, Education, and Employment and Psychological Distress by Latinx Subgroup

3.3. Race/Ethnicity as an Effect Modifier

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Lopez, M.H.; Krogstad, J.M.; Passel, J.S. Who is Hispanic? Pew Res. Cent. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/15/who-is-hispanic/ (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Bureau, U.C. Hispanic Population to Reach 111 Million by 2060. Census.gov. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2018/comm/hispanic-projected-pop.html (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Krogstad, J.M.; Passel, J.S.; Noe-Bustamante, L. Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month. Pew Res. Cent. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/23/key-facts-about-u-s-latinos-for-national-hispanic-heritage-month/ (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Alegría, M.; Mulvaney-Day, N.; Torres, M.; Polo, A.; Cao, Z.; Canino, G. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Across Latino Subgroups in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Mondragon, E.; Jimenez, A.; Palladino-Davis, A.G.; Davis, D.; Escamilla-Cejudo, J.A. Hispanic health in the USA: A scoping review of the literature. Public Health Rev. 2016, 37, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegría, M.; Woo, M. Conceptual Issues in Latino Mental Health. In Handbook of U.S. Latino Psychology: Developmental and Community-Based Perspectives; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 15–30. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-26806-002 (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Adame, J.L.; Lo, C.C.; Cheng, T.C. Ethnicity and Self-reported Depression Among Hispanic Immigrants in the U.S. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 58, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratter, J.L.; Eschbach, K. Race/Ethnic Differences in Nonspecific Psychological Distress: Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Soc. Sci. Q. 2005, 86, 620–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, M.; NeMoyer, A.; Bagué, I.F.; Wang, Y.; Alvarez, K. Social Determinants of Mental Health: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.M.; Hamann, H.A.; Mehl, M.R.; O’Connor, M.-F. The Hispanic health paradox: From epidemiological phenomenon to contribution opportunities for psychological science. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 19, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.M.; Chernenko, A.; Read, J.G. Region of origin diversity in immigrant health: Moving beyond the Mexican case. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 166, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, M.; Canino, G.; Shrout, P.E.; Woo, M.; Duan, N.; Vila, D.; Torres, M.; Chen, C.N.; Meng, X.L. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Sánchez, H.; Palloni, A.; Riosmena, F.; Wong, R. SES Gradients Among Mexicans in the United States and in Mexico: A New Twist to the Hispanic Paradox? Demography 2016, 53, 1555–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. Ethnic Variations in the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Psychological Distress among Latino Adults. Race Soc. Probl. 2011, 3, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, K.L.; Mattei, J.; Noel, S.E.; Collado, B.M.; Mendez, J.; Nelson, J.; Griffith, J.; Ordovas, J.M.; Falcon, L.M. The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a Longitudinal Cohort Study on Health Disparities in Puerto Rican Adults: Challenges and Opportunities. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.; McGuire, T.G.; Williams, D.R.; Wang, P. Mental Health in the Context of Health Disparities. AJP 2008, 165, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, P.J.; Good, B.J.; Kleinman, A. A critical review of epidemiological studies of Puerto Rican mental health. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, H.M.; Tarraf, W.; Whitfield, K.E.; Vega, W.A. The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the United States. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, E.; Jenks, D.; Chaikof, J.; Cione, C.; Felton, S.; Goris, I.; Buck, L.; Hershberg, E. Symptoms of PTSD and Depression among Central American Immigrant Youth. Trauma Care 2021, 1, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, R.D.; Parekh, A.; Wainberg, M.L.; Duarte, C.S.; Araya, R.; Oquendo, M.A. Hispanic immigrants in the USA: Social and mental health perspectives. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boen, C.E.; Hummer, R.A. Longer—But Harder—Lives?: The Hispanic Health Paradox and the Social Determinants of Racial, Ethnic, and Immigrant–Native Health Disparities from Midlife through Late Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2019, 60, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.M.; Wallace, S.P. Migration Circumstances, Psychological Distress, and Self-Rated Physical Health for Latino Immigrants in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislo, A.M.; Spence, N.J.; Gayman, M.D. The mental health and psychosocial adjustment of Cuban immigrants in south Florida. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, D.E.; Garza, D.M.; Cárdenas, V.; Marquine, M. Older Latino Mental Health: A Complicated Picture. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, igaa033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, R.C.; Gattamorta, K.A.; Berger-Cardoso, J. Examining Difference in Immigration Stress, Acculturation Stress and Mental Health Outcomes in Six Hispanic/Latino Nativity and Regional Groups. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Priest, N.; Anderson, N. Understanding Associations between Race, Socioeconomic Status and Health: Patterns and Prospects. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A.; Leavell, J.; Collins, C. Race, Socioeconomic Status and Health: Complexities, Ongoing Challenges and Research Opportunities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, I.I. Malignant Citizenship: Race, Imperialism, and Puerto Rico-United States Entanglements. Citizsh. Stud. 2021, 25, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria, M.; Shrout, P.E.; Canino, G.; Alvarez, K.; Wang, Y.; Bird, H.; Markle, S.L.; Ramos-Olazagasti, M.; Rivera, D.V.; Lê Cook, B.; et al. The effect of minority status and social context on the development of depression and anxiety: A longitudinal study of Puerto Rican descent youth. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 35, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Tehranifar, P. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Health Inequalities: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S28–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Link, B.G. A Retrospective on Fundamental Cause Theory: State of the Literature and Goals for the Future. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 47, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.M. Health Disparities, Politics, and the Maintenance of the Status Quo: A New Theory of Inequality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Bromet, E.; Cuitan, M.; Furukawa, T.A.; Gureje, O.; Hinkov, H.; Hu, C.Y.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 19, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: New York City, New York. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/newyorkcitynewyork (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Albrecht, S.S.; McVeigh, K.H. Investigation of the disparity between New York City and national prevalence of nonspecific psychological distress among Hispanics. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2012, 9, E52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossakowski, K.N. Dissecting the Influence of Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status on Mental Health in Young Adulthood. Res. Aging 2008, 30, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NHIS-Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. 30 September 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.T.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.J.; Sung, H.-Y.; Max, W.; Shi, Y.; Ong, M. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcón, L.M.; Todorova, I.; Tucker, K. Social support, life events, and psychological distress among the Puerto Rican population in the Boston area of the United States. Aging Ment. Health 2009, 13, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayón, C.; Nieri, T.; Gurrola, M. Latinx Immigrant Health and Mental Health. Encycl. Soc. Work. 2020. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-1299 (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Hinojosa, J.; Melendez, E.J. Puerto Rican Exodus: One Year Since Hurricane Maria. Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Research Brief Centro RB2018-05, Sep. 2018. Available online: https://centropr-archive.hunter.cuny.edu/sites/default/files/RB2018-05_SEPT2018%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2019).

- Alexander, M.; Polimis, K.; Zagheni, E. The Impact of Hurricane Maria on Out-Migration from Puerto Rico: Evidence from Facebook Data. SocArXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramutti, C.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Vos, S.R.; Schwartz, S.J. The Mental Health Impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and Florida. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benefits for Cuban/Haitian Entrants. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/fact-sheet/benefits-cuban/haitian-entrants (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Assari, S.; Lapeyrouse, L.M.; Neighbors, H.W. Income and Self-Rated Mental Health: Diminished Returns for High Income Black Americans. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, N.; Vargas, E.; Juarez, M.; Cacari-Stone, L.; Bettez, S. What’s Your ‘Street Race’? Leveraging Multidimensional Measures of Race and Intersectionality for Examining Physical and Mental Health Status among Latinxs. Sociol. Race Ethn. 2018, 4, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blacks’ Diminished Health Returns of Educational Attainment: Health and Retirement Study. J. Med. Res. Innov. 2020. Available online: https://jmrionline.com/jmri/article/view/212 (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Assari, S.; Bazargan, M. Minorities’ Diminished Returns of Educational Attainment on Hospitalization Risk: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Hosp. Pract. Res. 2019, 4, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unemployment, Behavioral Health, and Suicide|Health Affairs Brief. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20220302.274862/full/ (accessed on 23 February 2023).

| Characteristics (%) | Non-Latinx White | Mexican/ Mexican American | Central/ South American | Puerto Rican | Cuban/ Cuban American | Dominican | Other/ Multiple Latinx | Full Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 50.96 | 54.38 | 53.53 | 49.44 | 58.73 | 42.86 | 48.39 | 51.36 | |

| Female | 49.04 | 45.62 | 46.47 | 50.56 | 41.27 | 57.14 | 51.61 | 48.64 | |

| Age | |||||||||

| Under 65 | 90.83 | 96.87 | 95.62 | 96.88 | 92.42 | 97.11 | 95.98 | 91.76 | |

| Over 65 | 9.17 | 3.13 | 4.38 | 3.12 | 7.58 | 2.89 | 4.02 | 8.24 | |

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Currently Married | 48.51 | 46.57 | 47.04 | 36.99 | 48.28 | 40.63 | 29.89 | 47.93 | |

| Formerly Married | 19.3 | 15.45 | 16.27 | 18.23 | 17.89 | 22.26 | 18.07 | 18.80 | |

| Co-Habitating | 7.63 | 10.10 | 7.86 | 10.59 | 11.34 | 9.02 | 11.63 | 7.99 | |

| Never Married | 24.57 | 27.88 | 28.82 | 34.19 | 22.49 | 28.09 | 40.41 | 25.28 | |

| English Proficiency | |||||||||

| Very well/Well | 99.71 | 79.19 | 74.04 | 93.83 | 68.25 | 69.93 | 98.23 | 96.33 | |

| Not well | 0.24 | 14.53 | 19.38 | 5.02 | 18.32 | 22.04 | 1.36 | 2.63 | |

| Not at all | <0.01 | 6.28 | 6.58 | 1.15 | 13.43 | 8.03 | 0.41 | 1.05 | |

| Nativity Status | |||||||||

| US Born | 94.95 | 52.72 | 19.39 | 63.62 | 31.45 | 22.51 | 82.88 | 86.83 | |

| Foreign Born | 5.05 | 47.28 | 80.61 | 36.38 | 68.55 | 77.49 | 17.12 | 13.17 | |

| Citizenship Status | |||||||||

| US-Born | 94.95 | 52.72 | 19.39 | 63.62 | 31.45 | 22.51 | 82.88 | 86.83 | |

| Naturalized Citizen | 3.57 | 16.06 | 37.58 | 35.23 | 39.87 | 50.56 | 9.81 | 7.03 | |

| Non-Citizen | 1.49 | 31.22 | 43.03 | 1.15 | 28.68 | 26.93 | 7.31 | 6.14 | |

| Income | |||||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 16.45 | 21.49 | 21.37 | 19.32 | 14.56 | 21.75 | 20.69 | 17.19 | |

| $15,000 to $34,999 | 22.52 | 36.31 | 33.80 | 29.93 | 34.46 | 32.78 | 28.37 | 24.56 | |

| $35,000 to $74,999 | 33.32 | 25.71 | 25.34 | 29.59 | 27.31 | 24.19 | 30.29 | 32.13 | |

| $75,000+ | 19.96 | 7.58 | 9.06 | 10.67 | 12.39 | 8.40 | 10.83 | 18.05 | |

| Unknown | 7.75 | 8.92 | 10.43 | 10.49 | 11.29 | 12.88 | 9.83 | 8.07 | |

| Education | |||||||||

| Less than HS | 4.18 | 28.99 | 22.20 | 13.74 | 10.97 | 19.63 | 8.24 | 7.55 | |

| HS Graduate/GED | 19.94 | 27.09 | 21.59 | 25.17 | 27.94 | 25.82 | 21.27 | 20.90 | |

| Some College | 19.48 | 18.48 | 18.44 | 19.89 | 13.01 | 19.17 | 24.93 | 19.33 | |

| College/Advanced Degree | 56.39 | 25.44 | 37.77 | 41.20 | 48.07 | 35.38 | 45.57 | 52.21 | |

| Employment | |||||||||

| Employed | 89.04 | 90.10 | 89.59 | 87.97 | 92.75 | 91.50 | 85.70 | 89.17 | |

| Unemployed | 10.96 | 9.90 | 10.41 | 12.03 | 7.25 | 8.50 | 14.30 | 10.83 | |

| Psychological Distress | |||||||||

| Normal | 80.26 | 81.65 | 80.77 | 77.10 | 85.75 | 79.73 | 73.47 | 80.37 | |

| Moderate | 17.40 | 15.71 | 16.35 | 19.72 | 11.80 | 16.17 | 20.80 | 17.20 | |

| Severe | 2.35 | 2.64 | 2.88 | 3.18 | 2.44 | 4.10 | 5.73 | 2.43 | |

| General Health | |||||||||

| Good, Very Good, Excellent | 94.39 | 90.83 | 93.04 | 91.10 | 93.98 | 90.88 | 94.13 | 93.87 | |

| Fair, Poor | 5.66 | 9.17 | 6.96 | 8.90 | 6.02 | 9.12 | 5.87 | 6.13 | |

| Chronic Illness | |||||||||

| Diabetes (Yes) | 5.08 | 6.64 | 4.31 | 5.81 | 5.11 | 6.08 | 4.97 | 5.23 | |

| Heart Disease (Yes) | 2.36 | 1.24 | 1.13 | 1.72 | 2.42 | 2.43 | 1.57 | 2.20 | |

| Stroke (Yes) | 1.18 | 0.67 | 0.96 | 0.66 | 0.25 | 0.78 | 1.43 | 1.10 | |

| COPD (Yes) | 1.71 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.81 | 1.15 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1.51 | |

| Cancer (Yes) | 7.65 | 2.37 | 2.36 | 3.70 | 2.94 | 1.31 | 2.54 | 6.79 | |

| Sample Size | 58,765 | 7601 | 2235 | 1183 | 580 | 399 | 301 | 71,064 | |

| Full Sample (N = 71,064) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Moderate | Severe | |||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Psychological Distress | 57,164 | 80.37 | 12,125 | 17.20 | 1775 | 2.43 | |

| Income *** | |||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 5930 | 15.55 | 2878 | 22.64 | 620 | 33.02 | |

| $15,000 to $34,999 | 3485 | 23.30 | 3617 | 28.91 | 628 | 35.30 | |

| $35,000 to $74,999 | 3152 | 33.06 | 3516 | 29.45 | 340 | 20.38 | |

| $75,000+ | 10,851 | 19.66 | 1412 | 12.46 | 78 | 4.43 | |

| Unknown | 4295 | 8.43 | 702 | 6.55 | 109 | 6.87 | |

| Education *** | |||||||

| Less than HS | 4495 | 7.28 | 1065 | 8.04 | 244 | 12.97 | |

| HS Graduate/GED | 12,211 | 20.62 | 2676 | 21.22 | 490 | 27.91 | |

| Some College | 10,678 | 18.47 | 2737 | 22.43 | 461 | 25.84 | |

| College Degree | 29,780 | 53.62 | 5647 | 48.31 | 580 | 33.27 | |

| Employment *** | |||||||

| Employed | 51,501 | 90.34 | 10,444 | 86.00 | 1294 | 73.16 | |

| Unemployed | 5663 | 9.66 | 1681 | 14.00 | 481 | 26.84 | |

| Non-Latinx White | Mexican/Mexican American | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 47,256 | n = 10,106 | n = 1403 | n = 6167 | n = 1216 | n = 218 | ||

| Variables | Normal | Moderate | Severe | Normal | Moderate | Severe | |

| Psychological Distress ** | 80.26 | 17.40 | 2.35 | 81.65 | 15.71 | 2.64 | |

| Income | |||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 72.08 | 23.18 | 4.74 | 76.40 | 19.53 | 4.07 | |

| $15,000 to $34,999 | 75.05 | 21.38 | 3.56 | 80.62 | 16.46 | 2.92 | |

| $35,000 to $74,999 | 82.47 | 16.03 | 1.50 | 85.34 | 12.87 | 1.80 | |

| $75,000+ | 87.62 | 11.83 | 0.56 | 86.61 | 12.38 | 1.02 | |

| Unknown | 84.31 | 13.72 | 1.97 | 83.59 | 14.47 | 1.94 | |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than HS | 73.98 | 20.83 | 5.19 | 82.23 | 15.08 | 2.90 | |

| HS Graduate/GED | 78.66 | 18.06 | 3.28 | 82.26 | 12.87 | 2.87 | |

| Some College | 76.51 | 20.25 | 3.24 | 78.56 | 18.55 | 2.90 | |

| College Degree | 82.58 | 15.92 | 1.49 | 82.56 | 15.25 | 2.18 | |

| p < 0.001 | p = 0.118 | ||||||

| Employment | |||||||

| Employed | 81.30 | 16.80 | 1.90 | 82.39 | 15.26 | 2.34 | |

| Unemployed | 71.77 | 22.26 | 5.96 | 74.87 | 19.74 | 5.40 | |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Sample Size | 58,765 | 7601 | |||||

| Central/South American | Puerto Rican | ||||||

| n = 1795 | n = 375 | n = 65 | n = 908 | n = 236 | n = 39 | ||

| Variables | Normal | Moderate | Severe | Normal | Moderate | Severe | |

| Psychological Distress ** | 80.77 | 16.35 | 2.88 | 77.10 | 19.72 | 3.18 | |

| Income | |||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 72.86 | 22.36 | 4.79 | 70.66 | 23.42 | 5.92 | |

| $15,000 to $34,999 | 81.09 | 15.87 | 3.04 | 76.17 | 19.67 | 4.17 | |

| $35,000 to $74,999 | 84.19 | 14.40 | 1.41 | 78.00 | 19.58 | 2.41 | |

| $75,000+ | 84.85 | 13.72 | 1.43 | 90.26 | 8.74 | 0.00 | |

| Unknown | 84.14 | 12.60 | 3.26 | 75.73 | 23.60 | 0.67 | |

| p = 0.007 | p = 0.175 | ||||||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than HS | 77.44 | 18.76 | 3.80 | 73.71 | 19.65 | 6.64 | |

| HS Graduate/GED | 81.05 | 15.54 | 3.41 | 76.66 | 19.02 | 4.32 | |

| Some College | 78.79 | 16.91 | 4.30 | 76.33 | 20.71 | 2.96 | |

| College Degree | 83.54 | 15.12 | 1.33 | 78.88 | 19.69 | 1.43 | |

| p = 0.081 | p = 0.175 | ||||||

| Employment | |||||||

| Employed | 81.39 | 16.08 | 2.52 | 79.21 | 18.40 | 2.40 | |

| Unemployed | 75.46 | 18.62 | 5.92 | 61.74 | 29.38 | 8.88 | |

| p = 0.008 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Sample Size | 2235 | 1183 | |||||

| Cuban/Cuban American | Dominican | ||||||

| n = 495 | n = 71 | n = 14 | n = 316 | n = 65 | n = 18 | ||

| Variables | Normal | Moderate | Severe | Normal | Moderate | Severe | |

| Psychological Distress ** | 85.75 | 11.80 | 2.44 | 79.73 | 16.17 | 4.10 | |

| Income | |||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 77.39 | 18.58 | 4.03 | 80.79 | 15.38 | 3.84 | |

| $15,000 to $34,999 | 86.52 | 10.71 | 2.77 | 72.64 | 21.07 | 6.29 | |

| $35,000 to $74,999 | 88.72 | 10.73 | 0.55 | 80.14 | 17.27 | 2.59 | |

| $75,000+ | 84.29 | 13.89 | 1.81 | 97.06 | 2.94 | 0.00 | |

| Unknown | 88.63 | 6.65 | 4.71 | 83.94 | 11.60 | 4.46 | |

| p = 0.506 | p = 0.345 | ||||||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than HS | 85.76 | 8.36 | 5.88 | 72.64 | 21.41 | 5.95 | |

| HS Graduate/GED | 86.50 | 11.40 | 2.10 | 82.61 | 13.53 | 3.86 | |

| Some College | 81.04 | 15.76 | 3.20 | 81.80 | 13.67 | 4.52 | |

| College Degree | 86.60 | 11.75 | 1.66 | 80.44 | 16.54 | 3.01 | |

| p = 0.506 | p = 0.770 | ||||||

| Employment | |||||||

| Employed | 87.34 | 10.79 | 1.87 | 82.20 | 14.53 | 3.27 | |

| Unemployed | 65.44 | 24.74 | 9.82 | 53.12 | 33.86 | 13.02 | |

| p = 0.002 | p = 0.001 | ||||||

| Sample Size | 580 | 399 | |||||

| Other Latinx/Multiple Latinx | |||||||

| n = 227 | n = 56 | n = 18 | |||||

| Variables | Normal | Moderate | Severe | ||||

| Psychological Distress ** | 73.47 | 20.8 | 5.73 | ||||

| Income | |||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 63.58 | 30.21 | 6.21 | ||||

| $15,000 to $34,999 | 74.03 | 17.8 | 8.17 | ||||

| $35,000 to $74,999 | 81.24 | 15 | 3.76 | ||||

| $75,000+ | 74.5 | 22.9 | 2.6 | ||||

| Unknown | 67.6 | 25.2 | 7.2 | ||||

| p = 0.546 | |||||||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than HS | 63.2 | 30.11 | 6.68 | ||||

| HS Graduate/GED | 83 | 12.58 | 4.42 | ||||

| Some College | 70.27 | 24.6 | 5.13 | ||||

| College Degree | 72.63 | 20.87 | 6.5 | ||||

| p = 0.660 | |||||||

| Employment | |||||||

| Employed | 77.13 | 17.54 | 5.32 | ||||

| Unemployed | 51.5 | 40.32 | 8.18 | ||||

| p = 0.009 | |||||||

| Sample Size | 301 | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Female Sex (Male Ref) | 1.30 *** | 1.24–1.36 | 1.29 *** | 1.23–1.35 | 1.44 *** | 1.38–1.51 | 1.41 *** | 1.34–1.47 | 1.30 *** | 1.24–1.36 | |

| Less than 65 years old (65+ Ref) | 2.61 *** | 2.35–2.89 | 2.51 *** | 2.26–2.79 | 2.24 *** | 2.03–2.48 | 2.44 *** | 2.20–2.70 | 2.60 *** | 2.34–2.89 | |

| Marital Status (Married Ref) | |||||||||||

| Formerly Married | 1.66 *** | 1.56–1.77 | 1.68 *** | 1.58–1.78 | 1.66 *** | 1.56–1.77 | 1.71 *** | 1.61–1.82 | 1.66 *** | 1.56–1.77 | |

| Co-Habitating | 1.60 *** | 1.48–1.73 | 1.61 *** | 1.48–1.74 | 1.71 *** | 1.58–1.86 | 1.75 *** | 1.62–1.90 | 1.60 *** | 1.48–1.73 | |

| Never Married | 1.61 *** | 1.52–1.71 | 1.63 *** | 1.53–1.72 | 1.82 *** | 1.71–1.93 | 1.81 *** | 1.71–1.92 | 1.61 *** | 1.52–1.71 | |

| English Proficiency (Very well/well Ref) | |||||||||||

| Not well | 0.99 | 0.84–1.16 | 1.02 | 0.86–1.20 | 1.08 | 0.92–1.28 | 1.11 | 0.94–1.30 | 1.03 | 0.87–1.22 | |

| Not at all | 0.90 | 0.71–1.16 | 0.93 | 0.73–1.20 | 1.00 | 0.78–1.29 | 1.04 | 0.81–1.33 | 0.97 | 0.75–1.25 | |

| Born Outside of the U.S. (U.S. born Ref) | 0.87 * | 0.77–0.99 | 0.88 * | 0.78–1.00 | 0.92 | 0.81–1.05 | 0.90 | 0.80–1.02 | 0.91 | 0.80–1.03 | |

| Naturalized Citizen (U.S. born Citizen Ref) | 1.03 | 0.89–1.18 | 1.01 | 0.88–1.16 | 0.96 | 0.84–1.11 | 0.97 | 0.84–1.11 | 1.00 | 0.87–1.16 | |

| Survey Year (2014 Ref) | |||||||||||

| 2015 | 1.17 *** | 1.08–1.27 | 1.17 *** | 1.08–1.26 | 1.16 *** | 1.07–1.25 | 1.15 *** | 1.06–1.24 | 1.17 *** | 1.08–1.27 | |

| 2016 | 1.15 *** | 1.06–1.24 | 1.15 *** | 1.06–1.24 | 1.08 * | 1.00–1.17 | 1.08 + | 0.99–1.16 | 1.15 *** | 1.06–1.24 | |

| 2017 | 1.27 *** | 1.17–1.36 | 1.26 *** | 1.17–1.36 | 1.18 *** | 1.09–1.27 | 1.17 *** | 1.09–1.27 | 1.27 *** | 1.18–1.36 | |

| 2018 | 1.41 *** | 1.30–1.53 | 1.40 *** | 1.29–1.52 | 1.29 *** | 1.19–1.40 | 1.30 *** | 1.20–1.41 | 1.41 *** | 1.30–1.53 | |

| Health Conditions | |||||||||||

| Fair/Poor Health (Good Health Ref ⊥) | 3.72 *** | 3.43–4.04 | 3.83 *** | 3.53–4.16 | 3.97 *** | 3.66–4.31 | 3.94 *** | 3.63–4.28 | 3.72 *** | 3.43–4.04 | |

| Diabetes (None Ref) | 1.15 ** | 1.04–1.28 | 1.16 ** | 1.05–1.28 | 1.15 ** | 1.04–1.27 | 1.15 ** | 1.04–1.27 | 1.15 ** | 1.04–1.27 | |

| Coronary Heart Disease (None Ref) | 1.11 | 0.95–1.31 | 1.12 | 0.95–1.32 | 1.14 | 0.96–1.34 | 1.12 | 0.95–1.32 | 1.11 | 0.94–1.31 | |

| Stroke (None Ref) | 1.54 *** | 1.27–1.87 | 1.56 *** | 1.28–1.89 | 1.56 *** | 1.28–1.90 | 1.57 *** | 1.29–1.91 | 1.54 *** | 1.26–1.87 | |

| COPD (None Ref) | 1.57 *** | 1.34–1.85 | 1.59 *** | 1.36–1.87 | 1.64 *** | 1.39–1.92 | 1.65 *** | 1.41–1.94 | 1.57 *** | 1.33–1.84 | |

| Cancer (None Ref) | 1.11 * | 1.00–1.22 | 1.11 * | 1.01–1.23 | 1.09 + | 0.99–1.20 | 1.07 | 0.97–1.17 | 1.11 * | 1.01–1.22 | |

| Race and Ethnicity (non-Latinx white Ref) | |||||||||||

| Mexican/Mexican American | 0.79 *** | 0.72–0.87 | 0.73 *** | 0.63–0.85 | 0.65 *** | 0.53–0.79 | 0.88 ** | 0.80–0.96 | 0.64 *** | 0.50–0.82 | |

| Central/South American | 0.95 | 0.82–1.10 | 1.02 | 0.81–1.30 | 0.92 | 0.70–1.21 | 1.03 | 0.89–1.20 | 1.10 | 0.78–1.55 | |

| Puerto Rican | 1.01 | 0.86–1.20 | 1.04 | 0.75–1.44 | 0.93 | 0.60–1.44 | 1.02 | 0.85–1.23 | 0.82 | 0.48–1.39 | |

| Cuban/Cuban American | 0.74 * | 0.55–0.99 | 0.84 | 0.49–1.45 | 0.55 | 0.26–1.19 | 0.68 * | 0.50–0.93 | 0.55 | 0.23–1.33 | |

| Dominican | 0.89 | 0.67–1.18 | 0.58 | 0.30–1.13 | 1.03 | 0.57–1.87 | 0.85 | 0.65–1.12 | 0.52 | 0.22–1.23 | |

| Other Latinx/Multiple Latinx | 1.27 | 0.89–1.81 | 1.39 | 0.75–2.58 | 1.36 | 0.49–3.76 | 1.20 | 0.79–1.82 | 1.10 | 0.31–3.87 | |

| Income (<$15,000 Ref) | |||||||||||

| $15,000–$34,999 | 0.91 ** | 0.85–0.97 | 0.85 *** | 0.79–0.91 | 0.93 * | 0.86–1.00 | |||||

| $35,000–$74,999 | 0.66 *** | 0.61–0.71 | 0.58 *** | 0.54–0.62 | 0.65 *** | 0.60–0.70 | |||||

| $75,000+ | 0.50 *** | 0.46–0.55 | 0.43 *** | 0.39–0.47 | 0.49 *** | 0.45–0.54 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.55 *** | 0.49–0.61 | 0.48 *** | 0.43–0.54 | 0.52 *** | 0.47–0.59 | |||||

| Race and Ethnicity × Income | |||||||||||

| Mexican × $15,000–$34,999 | 1.03 | 0.85–1.25 | 0.99 | 0.81–1.20 | |||||||

| Mexican × $35,000–$74,999 | 1.12 | 0.90–1.40 | 1.04 | 0.83–1.31 | |||||||

| Mexican × $75,000+ | 1.44 * | 1.06–1.97 | 1.31 + | 0.95–1.79 | |||||||

| Mexican × Unknown | 1.31 + | 0.96–1.80 | 1.26 | 0.91–1.72 | |||||||

| Central/South × $15,000–$34,999 | 0.77 | 0.54–1.08 | 0.73+ | 0.52–1.02 | |||||||

| Central/South × $35,000–$74,999 | 0.97 | 0.67–1.40 | 0.97 | 0.67–1.40 | |||||||

| Central/South × $75,000+ | 1.32 | 0.75–2.33 | 1.36 | 0.75–2.47 | |||||||

| Central/South × Unknown | 0.91 | 0.55–1.50 | 0.87 | 0.53–1.43 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × $15,000–$34,999 | 0.79 | 0.50–1.27 | 0.83 | 0.52–1.33 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × $35,000–$74,999 | 1.17 | 0.74–1.84 | 1.23 | 0.76–1.99 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × $75,000 | 0.72 | 0.39–1.34 | 0.77 | 0.40–1.50 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × Unknown | 1.44 | 0.74–2.78 | 1.44 | 0.75–2.76 | |||||||

| Cuban × $15,000–$34,999 | 0.64 | 0.32–1.25 | 0.72 | 0.33–1.56 | |||||||

| Cuban × $35,000–$74,999 | 0.80 | 0.37–1.76 | 0.97 | 0.38–2.50 | |||||||

| Cuban × $75,000+ | 1.75 | 0.71–4.33 | 2.16 | 0.75–6.18 | |||||||

| Cuban × Unknown | 0.93 | 0.30–2.86 | 1.14 | 0.36–3.64 | |||||||

| Dominican × $15,000–$34,999 | 1.79 | 0.83–3.83 | 2.16 + | 0.95–4.91 | |||||||

| Dominican × $35,000–$74,999 | 1.92 | 0.81–4.56 | 2.48 + | 0.94–6.54 | |||||||

| Dominican × $75,000 | 0.38 | 0.07–2.00 | 0.39 | 0.09–1.77 | |||||||

| Dominican × Unknown | 1.85 | 0.54–6.31 | 1.96 | 0.61–6.27 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × $15,000–$34,999 | 0.79 | 0.31–2.00 | 0.97 | 0.28–3.41 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × $35,000–$74,999 | 0.67 | 0.30–1.50 | 0.87 | 0.31–2.43 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × $75,000+ | 1.77 | 0.49–6.33 | 2.30 | 0.49–10.88 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × Unknown | 1.62 | 0.52–5.06 | 2.19 | 0.60–7.93 | |||||||

| Education (Less than HS Ref) | |||||||||||

| HS Graduate/GED | 0.92 + | 0.84–1.01 | 0.83 ** | 0.74–0.94 | 0.88 * | 0.78–1.00 | |||||

| Some College | 0.99 | 0.90–1.09 | 0.91 | 0.81–1.03 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.06 | |||||

| College Degree | 0.90 * | 0.82–0.98 | 0.70 *** | 0.62–0.78 | 0.86 * | 0.76–0.96 | |||||

| Race and Ethnicity × Education | |||||||||||

| Mexican × HS Graduate/GED | 1.22 | 0.95–1.56 | 1.16 | 0.90–1.48 | |||||||

| Mexican × Some College | 1.28 + | 0.99–1.66 | 1.28 + | 0.99–1.66 | |||||||

| Mexican × College Degree | 1.40 ** | 1.10–1.78 | 1.28 * | 1.00–1.63 | |||||||

| Central/South × HS Graduate/GED | 0.98 | 0.66–1.47 | 0.92 | 0.61–1.38 | |||||||

| Central/South × Some College | 1.00 | 0.68–1.47 | 0.98 | 0.66–1.44 | |||||||

| Central/South × College Degree | 1.04 | 0.73–1.48 | 0.88 | 0.61–1.27 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × HS Graduate/GED | 1.10 | 0.63–1.93 | 1.12 | 0.66–1.93 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × Some College | 1.07 | 0.60–1.92 | 1.16 | 0.66–2.04 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × College Degree | 1.17 | 0.68–2.00 | 1.20 | 0.69–2.06 | |||||||

| Cuban × HS Graduate/GED | 1.10 | 0.47–2.62 | 1.12 | 0.45–2.79 | |||||||

| Cuban × Some College | 1.48 | 0.59–3.70 | 1.49 | 0.53–4.15 | |||||||

| Cuban × College Degree | 1.46 | 0.61–3.51 | 1.19 | 0.45–3.19 | |||||||

| Dominican × HS Graduate/GE | 0.68 | 0.32–1.47 | 0.64 | 0.27–1.50 | |||||||

| Dominican × Some College | 0.68 | 0.28–1.68 | 0.69 | 0.27–1.75 | |||||||

| Dominican × College Degree | 0.99 | 0.47–2.08 | 0.96 | 0.43–2.12 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × HS Graduate/GED | 0.57 | 0.15–2.15 | 0.66 | 0.18–2.49 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × Some College | 1.02 | 0.31–3.40 | 0.96 | 0.29–3.13 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × College Degree | 1.12 | 0.35–3.60 | 1.02 | 0.31–3.32 | |||||||

| Employment Status (Employed Ref) | 1.45 *** | 1.36–1.56 | 1.69 *** | 1.57–1.82 | 1.44 *** | 1.34–1.56 | |||||

| Race and Ethnicity × Employment Status | |||||||||||

| Mexican × Unemployed | 0.83 | 0.67–1.04 | 0.92 | 0.72–1.16 | |||||||

| Central/South × Unemployed | 0.76 | 0.53–1.10 | 0.85 | 0.59–1.22 | |||||||

| Puerto Rican × Unemployed | 1.25 | 0.79–1.98 | 1.35 | 0.85–2.16 | |||||||

| Cuban × Unemployed | 2.24 + | 0.86–5.78 | 2.37 + | 0.86–6.57 | |||||||

| Dominican × Unemployed | 2.14 + | 0.97–4.72 | 2.93 * | 1.17–7.34 | |||||||

| Other/Multiple × Unemployed | 1.55 | 0.69–3.52 | 1.64 | 0.58–4.65 | |||||||

| Observations | 71,064 | 71,064 | 71,064 | 71,064 | 71,064 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McSorley, A.-M.M.; Bacong, A.M. Associations between Socioeconomic Status and Psychological Distress: An Analysis of Disaggregated Latinx Subgroups Using Data from the National Health Interview Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064751

McSorley A-MM, Bacong AM. Associations between Socioeconomic Status and Psychological Distress: An Analysis of Disaggregated Latinx Subgroups Using Data from the National Health Interview Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064751

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcSorley, Anna-Michelle Marie, and Adrian Matias Bacong. 2023. "Associations between Socioeconomic Status and Psychological Distress: An Analysis of Disaggregated Latinx Subgroups Using Data from the National Health Interview Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064751

APA StyleMcSorley, A.-M. M., & Bacong, A. M. (2023). Associations between Socioeconomic Status and Psychological Distress: An Analysis of Disaggregated Latinx Subgroups Using Data from the National Health Interview Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064751