Narrative Review and Analysis of the Use of “Lifestyle” in Health Psychology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Concepts of Lifestyle

- Internal dimension: Lifestyle as a synonym for personality style, an expression of cognitive styles, or a set of attitudes, interests, and values. The focus is placed on the subject and on the internal processes that guide behaviour and action;

- External dimension: lifestyle as an expression of the individual’s status and social position within a given context or as an expression of behavioural patterns;

- Temporal dimension: lifestyle as a stable dimension that is expressed within daily practices; this dimension is found transversally in some sociological and psychological perspectives.

3.1.1. Internal Dimension

3.1.2. External Dimension

Social Positioning

Practice and Behaviour

3.1.3. Temporal Dimension

3.2. Lifestyle in the Field of Health Psychology

4. Discussion

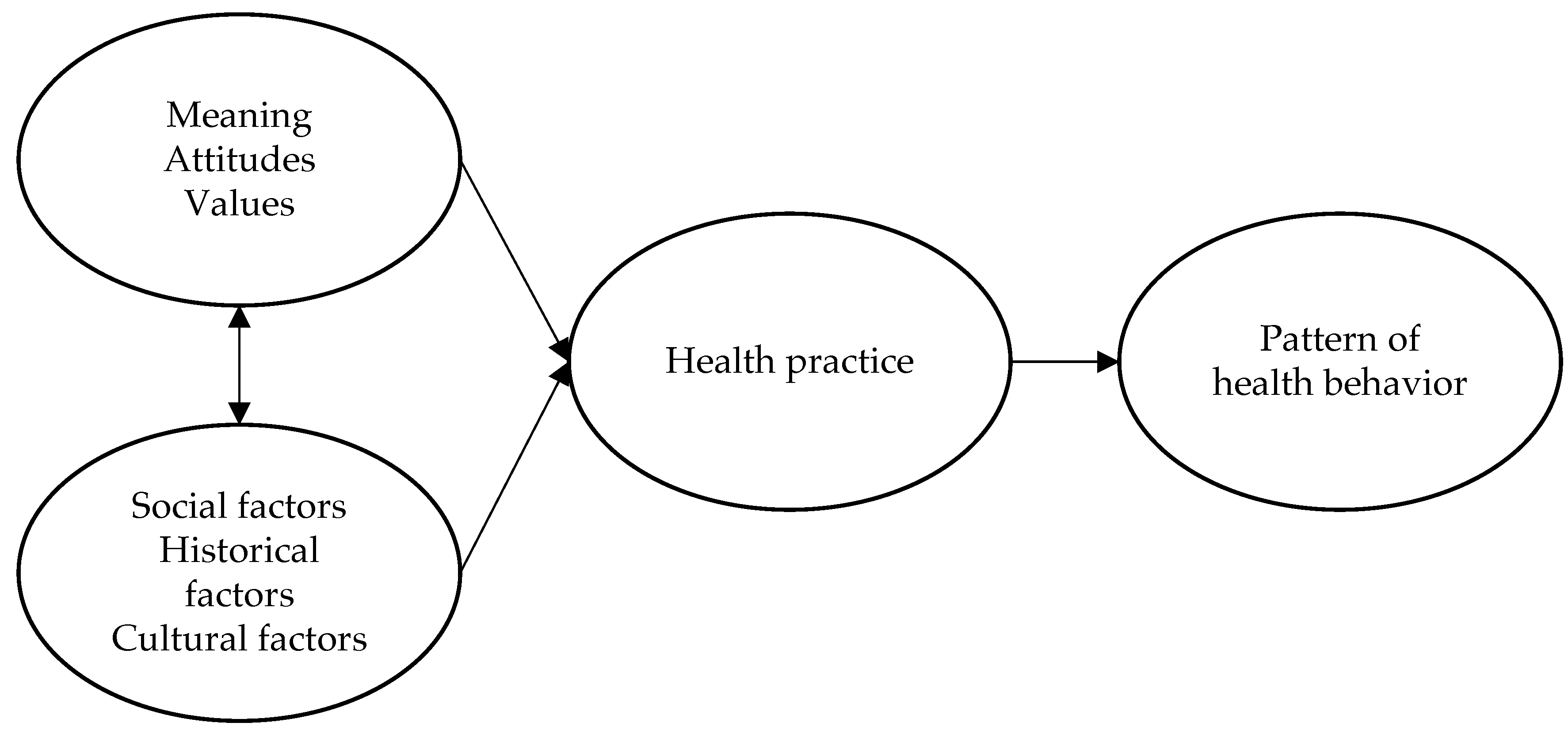

4.1. Toward a Perspective of Definition and Research on Lifestyle

4.2. System of Meanings, Attitudes, and Values within Which Subject Acts

4.3. Define Individual and Collective Models of Health Practices within Social, Historical, and Cultural Contexts

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buffon, L.G.L. Discours Prononcé a l’Académie Française Par M. De Buffon Le Jour de Sa Réception Le 25 Août 1753; J. Lecoffre: Paris, France, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, J. Familiar Quotations: A Collection of Passages, Phrases and Proverbs, Traced to Their Sources in Ancient and Modern Literature, 12th ed.; Morley, C., Everett, L.D., Eds.; Little, Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Ansbacher, H.L. Life Style: A Historical and Systematic Review. J. Individ. Psychol. 1967, 23, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weber, M. Class, Status and Party. In Class, Status, and Power; Bendix, R., Lipset, S., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-674-21277-0. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-8047-1944-5. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins, R.A. Lifestyle as a Generic Concept in Ethnographic Research. Qual. Quant. 1997, 31, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. Way of Life; SRI International: Stanford, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. The Nine American Lifestyles. Who We Are and Where We’re Going; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, H.G.; Baird, P.C.; Hawkes, G.R. Lifestyles and Consumer Behavior of Older Americans; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, A. Social Interest; Capricorn Books: New York, NY, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. Pattern and Growth in Personality; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1961; ISBN 978-0-03-010810-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gochman, D.S. Handbook of Health Behavior Research II: Provider Determinants; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-1-4899-1760-7. [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich, K.; Corin, E.; Potvin, L. A Theoretical Proposal for the Relationship Between Context and Disease. Sociol. Health Illn. 2001, 23, 776–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, J. Social Capital and Health: Implications for Public Health and Epidemiology. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweat, M.D.; Denison, J.A. Reducing HIV Incidence in Developing Countries with Structural and Environmental Interventions. AIDS 1995, 9, S251–S257. [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham, W.C.; Wolfe, J.D.; Bauldry, S. Health Lifestyles in Late Middle Age. Res. Aging 2020, 42, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, J.; Margolis, R.; Wright, L. Emerging Adulthood, Emergent Health Lifestyles: Sociodemographic Determinants of Trajectories of Smoking, Binge Drinking, Obesity, and Sedentary Behavior. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2017, 58, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, T.D. Profiles in Health: Multiple Roles and Health Lifestyles in Early Adulthood. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; Theory, Culture & Society; Sage Publications: London, UK; Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-8039-8345-8. [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks, C.; Johnson, S. A Socially Situated Approach to Inform Ways to Improve Health and Wellbeing. Sociol. Health Illn. 2014, 36, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases: Progress Monitor 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Hubert, H.B.; Bloch, D.A.; Oehlert, J.W.; Fries, J.F. Lifestyle Habits and Compression of Morbidity. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002, 57, M347–M351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.E.; Mainous, A.G.; Carnemolla, M.; Everett, C.J. Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Habits in US Adults, 1988–2006. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegler, I.; Kaplan, B.; Von Dras, D.; Mark, D. Cardiovascular Health: A Challenge for Midlife. In Life in the middle: Psychological and Social Development in Middle Age; Willis, S., Reid, J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Matarazzo, J.D. Behavioral Health: A 1990 Challenge for the Health Sciences Professions. In Behavioral Health: A Handbook of Health Enhancement and Disease Prevention; Matarazzo, J.D., Miller, N.E., Weiss, S.M., Herd, J.A., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1948.

- Huber, M.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Green, L.; van der Horst, H.; Jadad, A.R.; Kromhout, D.; Leonard, B.; Lorig, K.; Loureiro, M.I.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; et al. How Should We Define Health? BMJ 2011, 343, d4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. Guidelines for National Indicators of Subjective Well-Being and Ill-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2006, 7, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, Stress, and Coping; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-87589-412-6. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. The Salutogenic Model as a Theory to Guide Health Promotion1. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canguilhem, G. Le normal et le pathologique; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M. (Ed.) Critical Health Psychology; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-333-99033-9. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to Challenge the Spurious Hierarchy of Systematic over Narrative Reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veal, A.J. The Concept of Lifestyle: A Review. Leis. Stud. 1993, 12, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. Defining Lifestyle. Environ. Sci. 2007, 4, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M.E. Lifestyle and Social Structure: Concepts, Definitions, Analyses; Quantitative Studies in Social Relations; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-12-654280-6. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.C. Abnormal Psychology and Modern Life; Scott, Foresman: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986.

- Cockerham, W.C. The Social Determinants of the Decline of Life Expectancy in Russia and Eastern Europe: A Lifestyle Explanation. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. Lifestyle: Suggesting Mechanisms and a Definition from a Cognitive Science Perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A. Problems of Neurosis: A Book of Case Histories; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Sperry, J.; Sperry, L. Individual Psychology (Adler). In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 2227–2231. ISBN 978-3-319-24612-3. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.C. Personality Dynamics and Effective Behavior; Scott, Foresman: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. Beliefs, Attitudes, and Values: A Theory of Organization and Change; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1968; ISBN 978-0-87589-013-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. Life Way and Life Styles, Business Intelligence Program; SRI International: Stanford, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. Consumer Values. A Tipology, Value and Lifestyle Program; SRI International: Stanford, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Toward a Psychology of Being; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, W.T.; Golden, L.L. Lifestyle and Psychographics: A Critical Review and Recommendation. In Advances in Consumer Research; Kinnear, T.C., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1984; Volume 11, pp. 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Pessemier, E.A.; Tigert, D.J. Personality, Activity and Attitude Predictors of Consumer Behavior. In New Ideas for Successful Marketing, American Marketing; Whright, J.S., Goldstucker, J.L., Eds.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966; pp. 332–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, W.D. Backward Segmentation. In Insights into Consumer Behavior; Arndt, J., Ed.; Allyn and Bacon: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, W.D. Comment on the Meaning of LifeStyle. In Advances in Consumer Research; Anderson, B.B., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1975; p. 498. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.C. Homemaker Living Patterns and Marketplace Behavior—A Psychometric Approach. In New Ideas for Successful Marketing; Wright, J.S., Goldstucker, J.L., Eds.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966; pp. 305–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, W.D. Life Style and Psychographics; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Valette-Florence, P. Les Styles de vie: Bilan Critique et Perspectives; du Mythe à la Réalité; Connaître et Pratiquer la Gestion; Nathan: Paris, France, 1994; ISBN 978-2-09-192127-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cathelat, B. Les Styles de Vie des Français: 1978–1998; Au-Delà du Miroir; Stanké: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1977; ISBN 978-2-86242-003-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cathelat, B. Styles de Vie; Ed. d’Organisation: Paris, France, 1985; ISBN 978-2-7081-0625-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cathelat, B. Socio-Styles-Système: Les Styles de Vie, Théorie, Méthodes, Applications; Ed. d’Organisation: Paris, France, 1990; ISBN 978-2-7081-1176-9. [Google Scholar]

- Berzano, L.; Genova, C. Sociologia dei Lifestyles, Studi Superiori, 1st ed.; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-88-430-6030-6. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Wirtshaft und Gesellsschaft, Mohr, Tubingen as: Economy and Society; Roth, G., Wittich, C., Eds.; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1922; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Horley, J. A Longitudinal Examination of Lifestyles. Soc. Indic. Res. 1992, 26, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, I.R.; Higgs, P.; Ekerdt, D.J. Consumption and Generational Change: The Rise of Consumer Lifestyles. In Consumption and Generational Change: The Rise of Consumer Lifestyles; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-4128-0857-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, K.; Colomer, C.; Pérez-Hoyos, S. Research on Lifestyles and Health: Searching for Meaning. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, H.W.; Gilson, C.C. Consumer Behavior: Concepts and Strategies; Dickenson: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, D.C. Lifestyles; Key Ideas; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-415-11718-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dumazedier, J. Vers une Civilisation du Loisir? Points Série Civilisation; Ed. du Seuil: Paris, France, 1972; ISBN 978-2-02-000604-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, A.L. Style and Civilisation; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, M. Lifestyle Conformity and Lifecycle Saving: A Veblenian Perspective; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, D.A.; Baird, J.A. Discerning Intentions in Dynamic Human Action. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2001, 5, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, C.M.; Treur, J.; Wijngaards, W.C.A. A Temporal Modelling Environment for Internally Grounded Beliefs, Desires and Intentions. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2003, 4, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, M. The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-674-00582-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M.; Carpenter, M.; Call, J.; Behne, T.; Moll, H. Understanding and Sharing Intentions: The Origins of Cultural Cognition. Behav. Brain Sci. 2005, 28, 675–691; discussion 691–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, K.; McAdams, D.P. Personality Reconsidered: A New Agenda for Aging Research. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2003, 58, P296–P304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, L.; Caspi, A. Paths to Successful Development: Personality in the Life Course; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-521-80048-8. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Set like Plaster? Evidence for the Stability of Adult Personality. In Can Personality Change? Heatherton, T.F., Weinberger, J.L., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 21–40. ISBN 978-1-55798-213-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzus, C.; Roberts, B.W. Processes of Personality Development in Adulthood: The TESSERA Framework. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 21, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; DelVecchio, W.F. The Rank-Order Consistency of Personality Traits from Childhood to Old Age: A Quantitative Review of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerham, W.C. Health Lifestyle Theory and the Convergence of Agency and Structure. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M. Economy and Society, Volume 2; Roth, G., Wittich, C., Eds.; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- CSDH. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Alcántara, C.; Diaz, S.V.; Cosenzo, L.G.; Loucks, E.B.; Penedo, F.J.; Williams, N.J. Social Determinants as Moderators of the Effectiveness of Health Behavior Change Interventions: Scientific Gaps and Opportunities. Health Psychol. Rev. 2020, 14, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P. Health Disparities and Health Equity: Concepts and Measurement. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R. The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M. Social Determinants of Health Inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Korp, P. Problems of the Healthy Lifestyle Discourse. Sociol. Compass 2010, 4, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.H. Time, Human Agency, and Social Change: Perspectives on the Life Course. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1994, 57, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowsky, J.; Ross, C.E. Education, Social Status, and Health; Social Institutions and Social Change; A. de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-202-30706-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stainton Rogers, W. Changing Behaviour: Can Critical Psychology Influence Policy and Practice? In Advances in Health Psychology: Critical Approaches; Horrocks, C., Johnson, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke/Hampshire, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-230-27538-6. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, R. Health as a Meaningful Social Practice. Health 2006, 10, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B. The (Im)Possibility of Intellectual Work in Neoliberal Regimes. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2005, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R. Healthism and the Medicalization of Everyday Life. Int. J. Health Serv. 1980, 10, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassner, B. Fitness and the Postmodern Self. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1989, 30, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgetts, D.; Bolam, B.; Stephens, C. Mediation and the Construction of Contemporary Understandings of Health and Lifestyle. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakholok, O. The Idea of Healthy Lifestyle and Its Transformation Into Health-Oriented Lifestyle in Contemporary Society. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 2158244013500281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielewczyk, F.; Willig, C. Old Clothes and an Older Look: The Case for a Radical Makeover in Health Behaviour Research. Theory Psychol. 2007, 17, 811–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, A.; Chamberlain, K. The Problematic Messages of Nutritional Discourse: A Case-Based Critical Media Analysis. Appetite 2017, 108, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, M. Critical Health Psychology: Developing and Refining the Approach. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2007, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Poland, B. Health Psychology and Social Action. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 379–384, author reply 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The Problem with the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—An Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and Research in Psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.R.; Williams, D.R.; Onnela, J.-P.; Subramanian, S.V. A Multilevel Approach to Modeling Health Inequalities at the Intersection of Multiple Social Identities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 203, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, R.; McCarthy, W.J.; Yancey, A.K.; Lu, Y.; Patel, M. Resilience and Patterns of Health Risk Behaviors in California Adolescents. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollborn, S.; James-Hawkins, L.; Lawrence, E.; Fomby, P. Health Lifestyles in Early Childhood. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2014, 55, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollborn, S.; Lawrence, E. Family, Peer, and School Influences on Children’s Developing Health Lifestyles. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2018, 59, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint Onge, J.M.; Krueger, P.M. Health Lifestyle Behaviors among U. S. Adults. SSM Popul. Health 2017, 3, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvaro, C.; Jackson, L.A.; Kirk, S.; McHugh, T.L.; Hughes, J.; Chircop, A.; Lyons, R.F. Moving Canadian Governmental Policies beyond a Focus on Individual Lifestyle: Some Insights from Complexity and Critical Theories. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, F.; Fisher, M. Why Behavioural Health Promotion Endures despite Its Failure to Reduce Health Inequities. Sociol. Health Illn. 2014, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layte, R.; Whelan, C.T. Explaining Social Class Inequalities in Smoking: The Role of Education, Self-Efficacy, and Deprivation. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 25, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F. Cracking the Nut of Health Equity: Top down and Bottom up Pressure for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Promot. Educ. 2007, 14, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, K. Tobacco Control and Health Equality. Glob. Health Promot. 2010, 17, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.C.; Chamberlain, K. Health Psychology: A Critical Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-521-00526-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Dombrowski, S.U.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F. Theoretical Explanations for Maintenance of Behaviour Change: A Systematic Review of Behaviour Theories. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, D.; Murray, M.; Evans, B.; Willig, C.; Woodall, C.; Sykes, C.M. (Eds.) Health Psychology: Theory, Research and Practice, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-4129-0336-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophische Untersuchungen; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, B. Youth and Modern Lifestyle. In Youth Culture in Late Modernity; Fornas, J., Bolin, G., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are There Universal Aspects in the Structure and Contents of Human Values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.F. The Case for a Pluralist Health Psychology. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braibanti, P. Ripensare la Salute: Per un Riposizionamento Critico nella Psicologia della Salute; Psicologia Textbook; F. Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2015; ISBN 978-88-568-3563-2. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Definition | Research | Lifestyle Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adler (1933) [12] | “Their ability to show the individual living, acting, and dying as an indivisible whole in closest context with the tasks of his sphere of life rouses our admiration for their work to the highest degree” […] “the wholeness of his individuality.” | Psychology | Internal, temporal |

| Allport (1961) [13] | “The complex propriate organisation that determines the ‘total posture’ of a mature life-system.” […] [The lifestyle] “evolves gradually in the course of life, and day by day guides and unifies all, or at least many, of a person’s transactions with life.” | Psychology | Internal, temporal |

| Coleman (1964) [41] | “The general pattern of assumptions, motives, cognitive styles, and coping techniques that characterise the behavior of a given individual and give it consistency.” | Psychology | Internal, temporal |

| Schutz et al. (1979) [11] | “The orientation of self, others, and society that each individual develops and follow […] [it] reflects the values and cognitive style of individual. This orientation is derived from personal beliefs based on cultural context and the psycho-social milieu related to the stages of the individual’s life.” | Psychology | Internal |

| Mitchell, (1983 ) [9] | “We started from the premise that an individual’s array of inner values would create specific matching patterns of outer behavior –that is, of lifestyle.” | Psychology | Internal |

| WHO (1986) [42] | “Lifestyles are patterns of (behavioural) choices from the alternatives that are available to people according to their socio-economic circumstances and the ease with which they are able to choose certain ones over others.” | ||

| Giddens (1991) [6] | “A lifestyle can be defined as a more or less integrated set of practices which an individual embraces, not only because such practices fulfil utilitarian needs, but because they give material form to a particular narrative of self-identity.” “Lifestyles are routine practices, the routines incorporated into habits of dress, eating, modes of acting and favoured milieus for encountering others; but the routines followed are reflexively open to change in the light of the mobile nature of self-identity.” | Sociology | External, temporal |

| Veal (1993) [38] | “Lifestyle is the distinctive pattern of personal and social behaviour characteristic of an individual or a group.” | Sociology | External, temporal |

| Stebbins (1997) [7] | “A lifestyle is a distinctive set of shared patterns of tangible behavior that is organised around a set of coherent interests or social condition or both, that is explained and justified by a set of values, attitudes, and orientations and that, under certain conditions, becomes the basis for a separate, common social identity for its participants” and “lifestyle are not entirely individual […] but are constructed through affiliation and negotiation, by the active integration of the individual and society, which are constantly […] reproduced through each other.” | Sociology | Internal, temporal |

| Cockerham et al. (1997) [43] | “Collective patterns of health-related behaviour based on choices from options available to people according to their life chances.” | Sociology | External, temporal |

| Jensen (2009) [44] | “A lifestyle is a pattern of repeated acts that are both dynamic and to some degree hidden to the individual, and they involve the use of artefacts. This lifestyle is founded on beliefs about the world, and its constancy over time is led by intentions to attain goals or sub-goals that are desired. In other words, a lifestyle is a set of habits that are directed by the same main goal.” | Psychology | External, temporal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brivio, F.; Viganò, A.; Paterna, A.; Palena, N.; Greco, A. Narrative Review and Analysis of the Use of “Lifestyle” in Health Psychology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054427

Brivio F, Viganò A, Paterna A, Palena N, Greco A. Narrative Review and Analysis of the Use of “Lifestyle” in Health Psychology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054427

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrivio, Francesca, Anna Viganò, Annalisa Paterna, Nicola Palena, and Andrea Greco. 2023. "Narrative Review and Analysis of the Use of “Lifestyle” in Health Psychology" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054427

APA StyleBrivio, F., Viganò, A., Paterna, A., Palena, N., & Greco, A. (2023). Narrative Review and Analysis of the Use of “Lifestyle” in Health Psychology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054427