The Role of Shame, Stigma, and Family Communication Patterns in the Decision to Disclose STIs to Parents in Order to Seek Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Transition to Emerging Adulthood

2.2. The Disclosure Decision-Making Model and Decisions to Disclose

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedures

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Information Assessment

3.3.2. Relational Quality

3.3.3. Disclosure Efficacy

3.3.4. Likelihood of Disclosing to Parent

3.3.5. Likelihood of Disclosing to Third Party

4. Results

4.1. Analyses

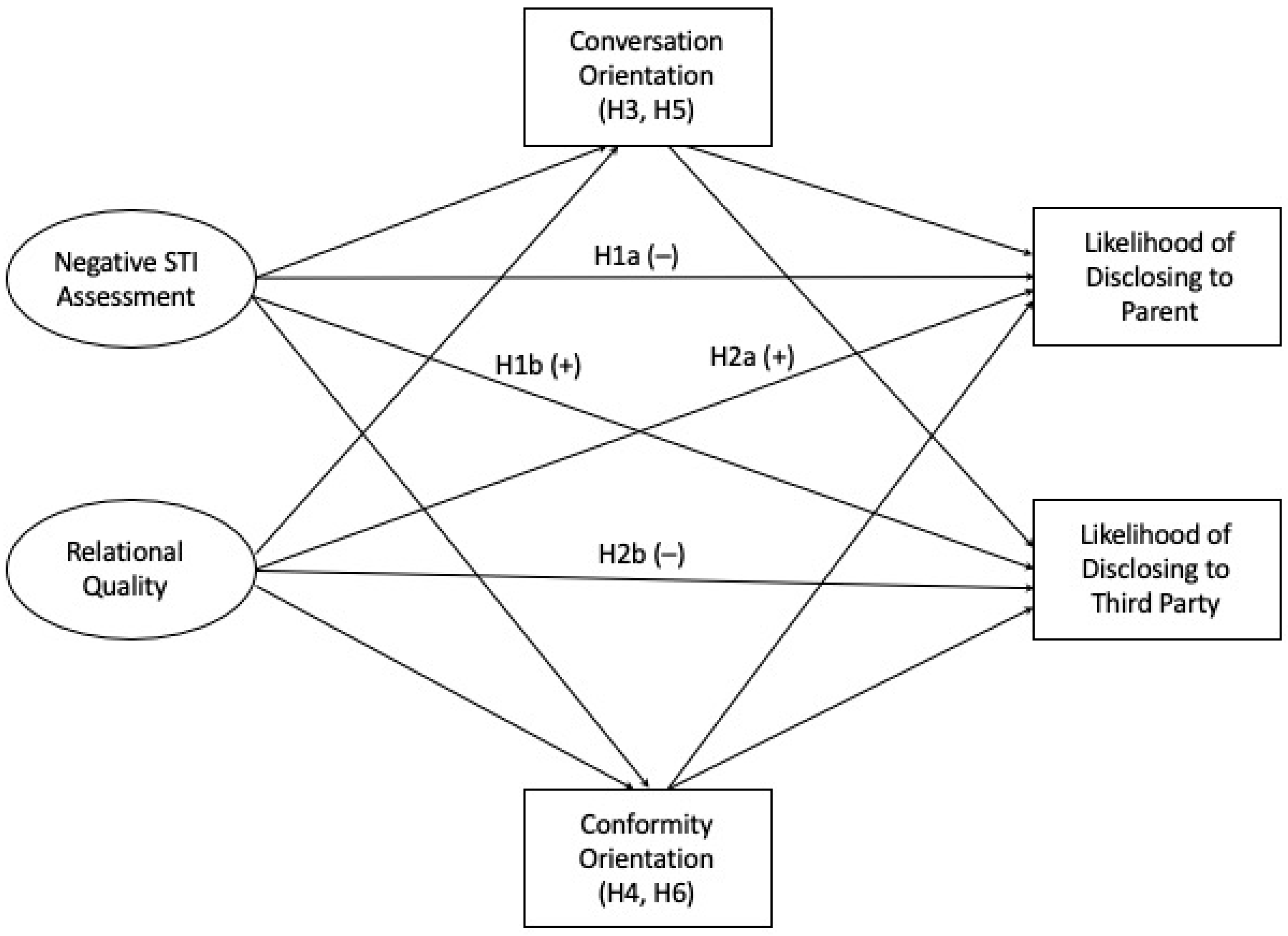

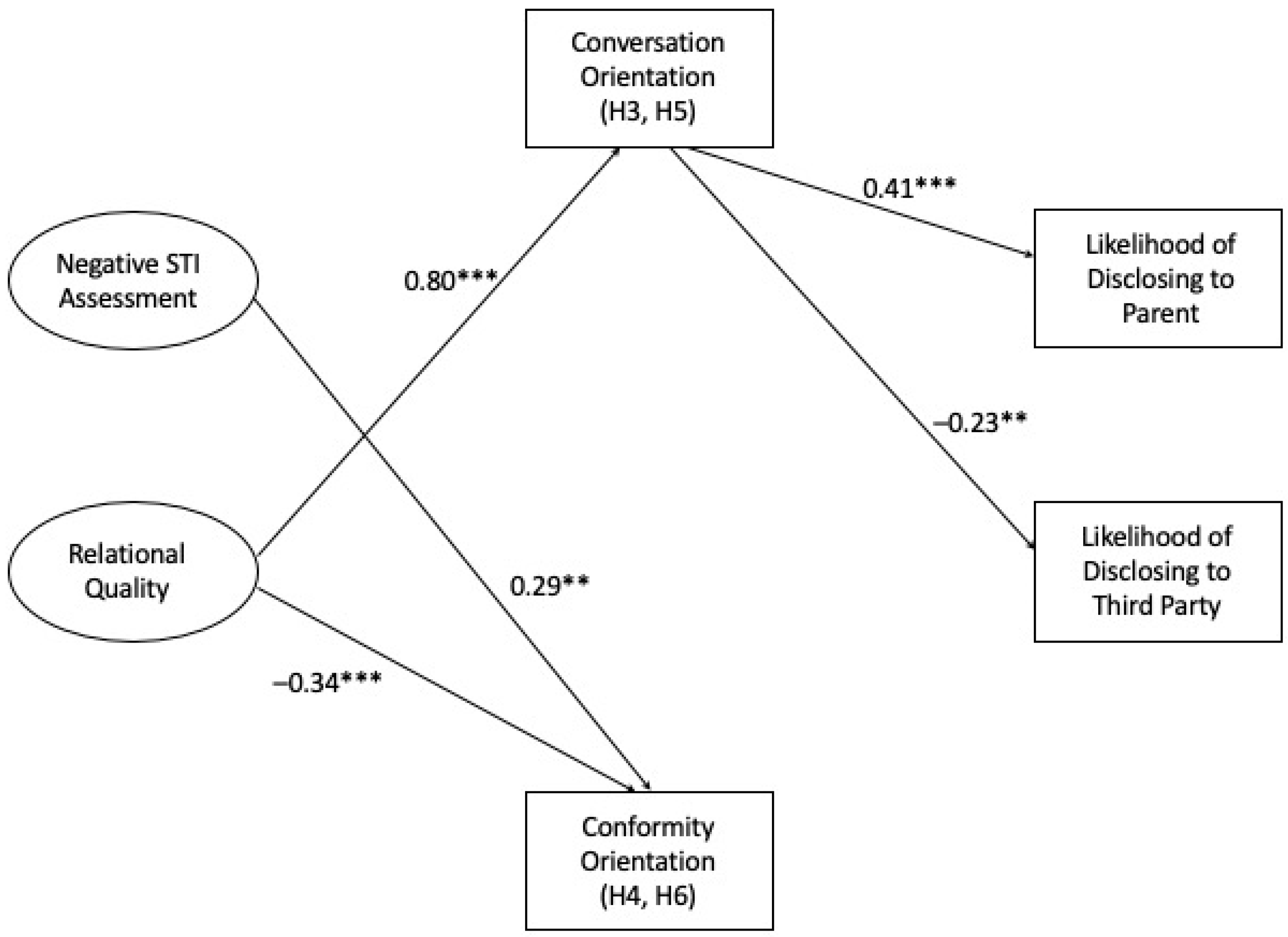

4.2. Hypothesis 1

4.3. Hypothesis 2

4.4. Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 5

4.5. Hypothesis 4 and Hypothesis 6

5. Discussion

5.1. The Role of Stigma and Shame

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs): STD Awareness Month; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- Satterwhite, C.L.; Torrone, E.; Meites, E.; Dunne, E.F.; Mahajan, R.; Ocfemia, M.C.; Su, J.; Xu, F.; Weinstock, H. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: Prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013, 40, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefkowitz, E.S. “Things have Gotten Better” Developmental Changes among Emerging Adults after the Transition to University. J. Adolesc. Res. 2005, 20, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, A. The Contexts of Sexual Involvement and Concurrent Sexual Partnerships. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2010, 42, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; Granato, H.; Blayney, J.A.; Lostutter, T.W.; Kilmer, J.R. Predictors of Hooking Up Sexual Behaviors and Emotional Reactions among US College Students. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; Craft, E.A. Protecting One’s Self from a Stigmatized Disease…once one has it. Deviant Behav. 2002, 23, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, D.C.; McCabe, M. Effects of Sexually Transmitted Infection Status, Relationship Status, and Disclosure Status on Sexual Self-Concept. J. Sex. Res. 2008, 45, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC Fact Sheet: Information for Teens and Young Adults: Staying Healthy and Preventing STDs; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Scheinfeld, E. Shame and STIs: An Exploration of Emerging Adult Students’ Felt Shame and Stigma Towards Getting Tested for and Disclosing Sexually Transmitted Infections. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K. An integrated model of health disclosure decision-making. In Uncertainty, Information Management, and Disclosure Decisions: Theories and Applications; Afifi, T.D., Afifi, W.A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 226–253. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.; Li, X.; Stanton, B. Disclosure of Parental HIV Infection to Children: A Systematic Review of Global Literature. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFebvre, L.E.; Carmack, H.J. Catching Feelings: Exploring Commitment (Un) Readiness in Emerging Adulthood. JSPR 2020, 37, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licoppe, C. Liquidity and Attachment in the Mobile Hookup Culture. A Comparative Study of Contrasted Interactional Patterns in the Main Uses of Grindr and Tinder. J. Cult. Econ. 2020, 13, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotevant, H.D.; Cooper, C.R. Individuation in Family Relationships. Hum. Dev. 1986, 29, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronio, S. Privacy Binds in Family Interactions: The Case of Parental Privacy Invasion; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter, A.M.; Heiss, S.; Sibal, K.; Lev, E.; Battle-Fisher, M.; Shubert, N. Parental Invasive and Children’s Defensive Behaviors at Home and Away at College: Mediated Communication and Privacy Boundary Management. Commun. Stud. 2010, 61, 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinfeld, E.; Worley, T. Understanding the Parent-Child Relationship during the Transition into College and Emerging Adulthood using the Relational Turbulence Theory. Commun. Q. 2018, 66, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, T.R.; Mucci-Ferris, M. Parent–student Relational Turbulence, Support Processes, and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JSPR 2021, 38, 3010–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castilla Gil, R.R.; Cerezo, M.L.; Estrada, R.C. Adolescents and their Sources of Information on Sexuality: Preferences and Perceived Usefulness. Aten Primaria 2001, 27, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente, R.J.; Wingood, G.M.; Crosby, R.; Cobb, B.K.; Harrington, K.; Davies, S.L. Parent-Adolescent Communication and Sexual Risk Behaviors among African American Adolescent Females. J. Pediatr. 2001, 139, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, A.; Kellas, J.K. High School Adolescents’ Perceptions of the Parent–child Sex Talk: How Communication, Relational, and Family Factors Relate to Sexual Health. South Commun. J. 2015, 80, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, J.M.; Milhausen, R.R.; Wingood, G.M.; DiClemente, R.J.; Salazar, L.F.; Crosby, R.A. Validation of a Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale for use in STD/HIV Prevention Interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2008, 35, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.C.; Blitstein, J.L.; Evans, W.D.; Kamyab, K. Impact of a Parent-Child Sexual Communication Campaign: Results from a Controlled Efficacy Trial of Parents. Reprod. Health 2010, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.C.; Evans, W.D.; Kamyab, K. Effectiveness of a National Media Campaign to Promote Parent–child Communication about Sex. Health Educ. Behav. 2013, 40, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistella, C.L.Y.; Bonati, F.A. Communication about Sexual Behavior among Adolescent Women, their Family, and Peers. Fam. Soc. 1998, 79, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, D.D.; Meanley, S.P.; Bond, K.T.; Agenor, M.; Relf, M.V.; Barroso, J.V. Topics for Inclusive Parent-Child Sex Communication by Gay, Bisexual, Queer Youth. Behav. Med. 2021, 47, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nack, A. Bad Girls and Fallen Women: Chronic STD Diagnoses as Gateways to Tribal Stigma. Symb. Interact. 2002, 25, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloep, M.; Hendry, L.B. Letting Go Or Holding on? Parents’ Perceptions of their Relationships with their Children during Emerging Adulthood. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 28, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friley, L.B.; Venetis, M.K. Decision-Making Criteria when Contemplating Disclosure of Transgender Identity to Medical Providers. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.R.; Birnholtz, J. “I Don’t Want them to Not Know” Investigating Decisions to Disclose Transgender Identity on Dating Platforms. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, L.M.; Brothers, S.L.; Lang, A. Self-Disclosure Patterns among Children and Youth with Epilepsy: Impact of Perceived-Stigma. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2023, 14, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulginiti, A. Applying the Disclosure Decision-Making Model to Suicide-Related Disclosure: A Theory-Informed Multilevel Social Network Analysis. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 2021; online advance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, E.E.; Shannon, K.L.; Pitchford, B. Adolescents’ Disclosure of Mental Illness to Parents: Preferences and Barriers. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, V.; Ahmed, H.; Lindsay, S. Unravelling the Complexities of Disclosure for Employees with Non-Visible Disabilities/Illnesses at Work: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalibi, N.; Forte, A. Announcing Pregnancy Loss on Facebook: A Decision-Making Framework for Stigmatized Disclosures on Identified Social Network Sites. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21 April 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, K.; Magsamen-Conrad, K.; Venetis, M.K.; Checton, M.G.; Bagdasarov, Z.; Banerjee, S.C. Assessing Health Diagnosis Disclosure Decisions in Relationships: Testing the Disclosure Decision-Making Model. Health Commun. 2012, 27, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K. An integrated model of health disclosure decision-making. In Uncertainty, Information Management, and Disclosure Decisions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 242–269. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner, A.F.; Fitzpatrick, M.A. Toward a Theory of Family Communication. Commun. Theory 2002, 12, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.A.; Marshall, L.J.; Leutwiler, T.J.; Krcmar, M. The Effect of Family Communication Environments on Children’s Social Behavior during Middle Childhood. Commun. Res. 1996, 23, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, M.C.; Schrodt, P. Privacy Orientations as a Function of Family Communication Patterns. Commun. Rep. 2013, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, E.A.; Hesse, C.; Miller, S.; Ford, W.; Youngs, E.L. Privacy and Family Communication about Genetic Cancer Risk: Investigating Factors Promoting Women’s Disclosure Decisions. J. Fam. Commun. 2015, 15, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, A.; Maliski, R.; Warner, B. Analyzing the Effects of Family Communication Patterns on the Decision to Disclose a Health Issue to a Parent: The Benefits of Conversation and Dangers of Conformity. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.N.; Hovick, S.R. The Indirect Effect of Family Communication Patterns on Young Adults’ Health Self-Disclosure: Understanding the Role of Descriptive and Injunctive Norms in a Test of the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction. Commun. Rep. 2021, 34, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checton, M.G.; Greene, K.; Magsamen-Conrad, K.; Venetis, M.K. Patients’ and Partners’ Perspectives of Chronic Illness and its Management. Fam. Syst. Health 2012, 30, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortenberry, J.D.; McFarlane, M.; Bleakley, A.; Bull, S.; Fishbein, M.; Grimley, D.M.; Malotte, C.K.; Stoner, B.P. Relationships of Stigma and Shame to Gonorrhea and HIV Screening. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Z. Measurement of Romantic Love. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1970, 16, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larzelere, R.E.; Huston, T.L. The Dyadic Trust Scale: Toward Understanding Interpersonal Trust in Close Relationships. J. Marriage Fam. 1980, 42, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, T.D.; Moors, A.C.; Ziegler, A.; Feltner, M.R. Trust and Satisfaction in Adult Child–mother (and Other) Relationships. BASP 2011, 33, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Chapter 26: Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In The SAGE Handbook of Innovation in Social Research Methods; Williams, M., Vogt, W.P., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bogle, K.A. The Shift from Dating to Hooking Up in College: What Scholars have Missed. Sociol. Compass 2007, 1, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetis, M.K.; Chernichky-Karcher, S.M.; Lillie, H.M. Communicating Resilience: Predictors and Outcomes of Dyadic Communication Resilience Processes among both Cancer Patients and Cancer Partners. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2020, 48, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scheinfeld, E. The Role of Shame, Stigma, and Family Communication Patterns in the Decision to Disclose STIs to Parents in Order to Seek Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064742

Scheinfeld E. The Role of Shame, Stigma, and Family Communication Patterns in the Decision to Disclose STIs to Parents in Order to Seek Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064742

Chicago/Turabian StyleScheinfeld, Emily. 2023. "The Role of Shame, Stigma, and Family Communication Patterns in the Decision to Disclose STIs to Parents in Order to Seek Support" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064742

APA StyleScheinfeld, E. (2023). The Role of Shame, Stigma, and Family Communication Patterns in the Decision to Disclose STIs to Parents in Order to Seek Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064742