Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS and Related Factors in Angolans Aged between 15 and 49 Years

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- (i)

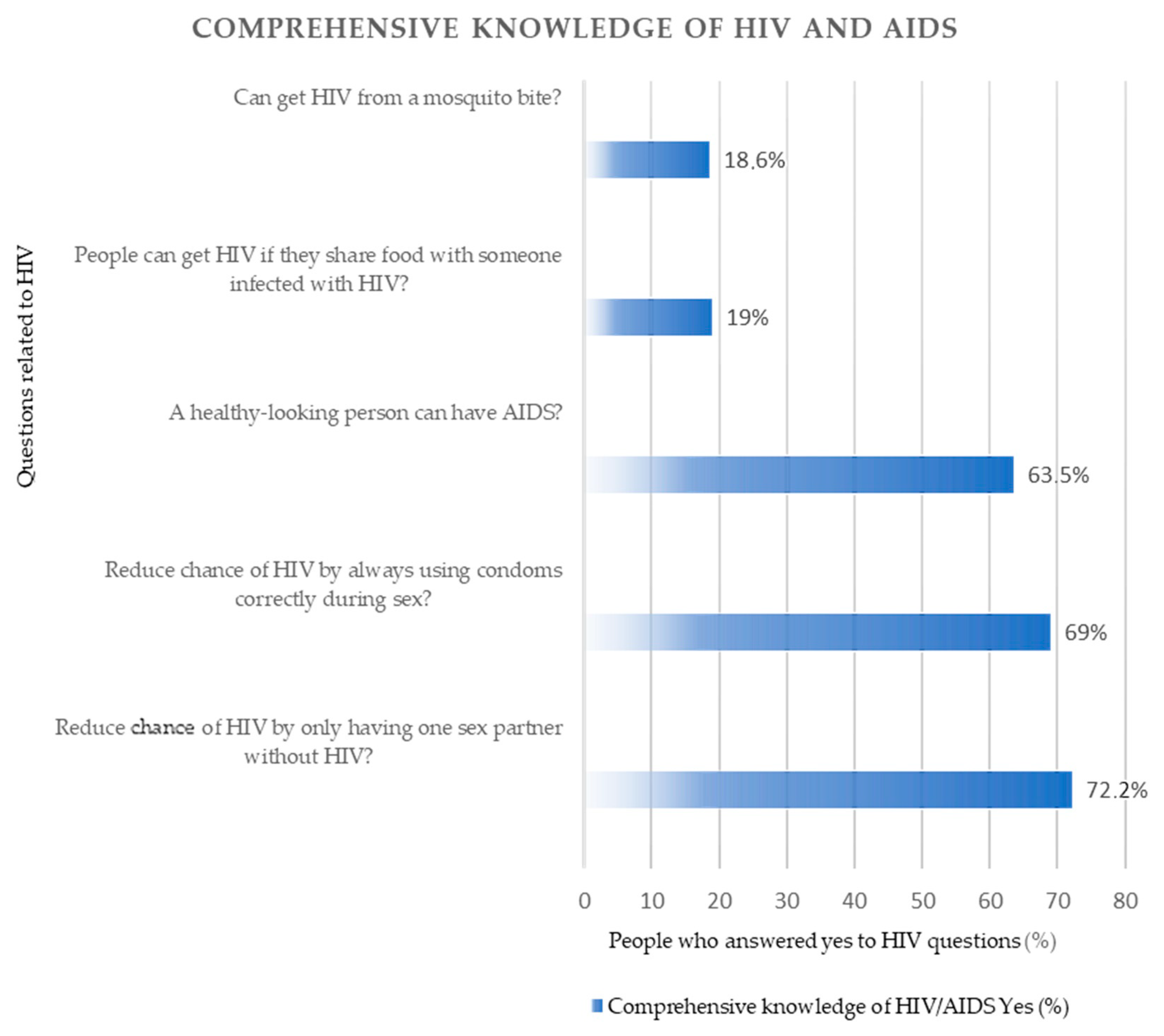

- Can you get HIV from a mosquito bite?

- (ii)

- Can we reduce the chance of HIV by always using condoms correctly during sex?

- (iii)

- People can get HIV if they share food with someone infected with HIV?

- (iv)

- A healthy-looking person can have HIV/AIDS?

- (v)

- Can we reduce the chance of HIV by only having one sex partner without HIV?

- I.

- In the first step, we computed the comprehensive knowledge of HIV and AIDS variable.

- II.

- In the second, step we used the chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test to analyze the associations between having comprehensive knowledge of HIV and AIDS and each independent variable.

- III.

- Then, we performed a multivariable logistic regression to determine associations. The relationship between the predictor and outcome variables was estimated using odds ratio (ORs) with a 95% confidence interval (CIs).

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS in Angola

3.3. Factors Associated with Having a Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS in Angola

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jahagirdar, D.; Walters, M.K.; Novotney, A.; Brewer, E.D.; Frank, T.D.; Carter, A.; Biehl, M.H.; Abbastabar, H.; Abhilash, E.S.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; et al. Global, regional, and national sex-specific burden and control of the HIV epidemic, 1990–2019, for 204 countries and territories: The Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e633–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Económica dos Estados da África Ocidental. Estratégia Regional Para o VIH, Tuberculose, Hepatite B e C, e Saúde Reprodutiva e Sexual e Direito Entre as Populações-Chave na Comunidade Económica dos Estados da África Ocidental. CEDEAO, UNDP, ONUSIDA, Eds.; CEDEAO, ECOWAS: Burkina Faso, 2020; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Areri, H.; Marshall, A.; Harvey, G. Factors influencing self-management of adults living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy in Northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tique, J.A.; Howard, L.M.; Gaveta, S.; Sidat, M.; Rothman, R.L.; Vermund, S.H.; Ciampa, P.J. Measuring Health Literacy Among Adults with HIV Infection in Mozambique: Development and Validation of the HIV Literacy Test. Aids Behav. 2017, 21, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwamahoro, N.S.; Ngwira, B.; Vinther-Jensen, K.; Rowlands, G. Health literacy among Malawian HIV-positive youth: A qualitative needs assessment and conceptualization. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, G.; Barragan, M.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Williams, M.V.; del Rio, C. Health literacy is a predictor of HIV/AIDS knowledge. Fam. Med. 2006, 38, 717–723. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Literacy Toolkit for Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Series of Information Sheets to Empower Communities and Strengthen Health Systems; Dodson, S., Good, S., Osborne, R., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Teshale, A.B.; Yeshaw, Y.; Alem, A.Z.; Ayalew, H.G.; Liyew, A.M.; Tessema, Z.T.; Tesema, G.A.; Worku, M.G.; Alamneh, T.S. Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS and associated factors among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel analysis using the most recent demographic and health survey of each country. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Country Factsheets Angola. 2020. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/angola (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Son, N.V.; Luan, H.D.; Tuan, H.X.; Cuong, L.M.; Duong, N.T.T.; Kien, V.D. Trends and Factors Associated with Comprehensive Knowledge about HIV among Women in Vietnam. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadawi, A.; Mirghani, H. Assessment of HIV/AIDS comprehensive correct knowledge among Sudanese university: A cross-sectional analytic study 2014. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 24, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachega, J.B.; Mutamba, B.; Basangwa, D.; Nguyen, H.; Dowdy, D.W.; Mills, E.J.; Katabira, E.; Nakimuli-Mpungu, E. Severe mental illness at ART initiation is associated with worse retention in care among HIV-infected Ugandan adults. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2013, 18, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perazzo, J.; Reyes, D.; Webel, A. A Systematic Review of Health Literacy Interventions for People Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, J.; Biswas, R.K. Knowledge About HIV/AIDS and Its Transmission and Misconception Among Women in Bangladesh. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 2542–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budu, E.; Seidu, A.A.; Armah-Ansah, E.K.; Mohammed, A.; Adu, C.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Ahinkorah, B.O. What has comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge got to do with HIV testing among men in Kenya and Mozambique? Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2021, 54, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estifanos, T.M.; Hui, C.; Tesfai, A.W.; Teklu, M.E.; Ghebrehiwet, M.A.; Embaye, K.S.; Andegiorgish, A.K. Predictors of HIV/AIDS comprehensive knowledge and acceptance attitude towards people living with HIV/AIDS among unmarried young females in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandiwa, C.; Namondwe, B.; Munthali, M. Prevalence and correlates of comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge among adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years in Malawi: Evidence from the 2015-16 Malawi demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palella, F.J., Jr.; Baker, R.K.; Moorman, A.C.; Chmiel, J.S.; Wood, K.C.; Brooks, J.T.; Holmberg, S.D. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: Changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006, 43, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtzman, C.W.; Brady, K.A.; Yehia, B.R. Retention in care and medication adherence: Current challenges to antiretroviral therapy success. Drugs 2015, 75, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chory, A.; Nyandiko, W.; Martin, R.; Aluoch, J.; Scanlon, M.; Ashimosi, C.; Njoroge, T.; McAteer, C.; Apondi, E.; Vreeman, R. HIV-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, Behaviors and Experiences of Kenyan Adolescents Living with HIV Revealed in WhatsApp Group Chats. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2021, 20, 2325958221999579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudelson, C.; Cluver, L. Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, G.H.d.; Galvão, M.T.G.; Pinheiro, P.N.d.C.; Vieira, N.F.C. Health literacy for people living with HIV/Aids: An integrative review. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. Poor health literacy: A ‘hidden’ risk factor. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 7, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawuki, J.; Gatasi, G.; Sserwanja, Q.; Mukunya, D.; Musaba, M.W. Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS and associated factors among adolescent girls in Rwanda: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, D.E.E.; Oliveira, C. Study of the Digital Skills of the “Sons of War” of Angola, a contribution. Indagatio Didact. 2020, 12, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, S.A.; Wang, Y.; Tesfamariam, E.H. Predictors of HIV/AIDS knowledge and attitude among young women of Nigeria and Democratic Republic of Congo: Cross-sectional study. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 2017, 8, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, B.; Anyiam, F.E.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Budu, E.; Seidu, A.A.; Yaya, S. Women’s decision-making capacity and its association with comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS in 23 sub-Saharan African countries. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetteh, J.K.; Frimpong, J.B.; Budu, E.; Adu, C.; Mohammed, A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.-A. Comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV testing among men in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel modelling. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2021, 54, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE); Ministério da Saúde (MINSA); Ministério do Planeamento e do Desenvolvimento Territorial (MINPLAN) e ICF International. Inquérito de Indicadores Múltiplos e de Saúde em Angola 2015–2016; INE, MINSA, MINPLAN: Luanda, Angola; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017.

- Bank, W. World Development Indicators/The World by Income and Region. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Agency, C.I. Angola Profile. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_ao.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Gyeltshen, D.; Musa, S.S.; Amesho, J.N.; Ewelike, S.C.; Bayoh, A.V.S.; Al-Sammour, C.; Camua, A.A.; Lin, X.; Lowe, M.; Ahmadi, A.; et al. COVID-19: A novel burden on the fragile health system of Angola. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 03059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Ramos, N.N.V.; Fronteira, I.; Martins, M.R.O. Building a Health Literacy Indicator from Angola Demographic and Health Survey in 2015/2016. Int J Env. Res Public Health 2022, 19, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Demographic and Health Surveys Program. Guide to DHS Statistics. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/index.htm#t=Guide_to_DHS_Statistics_DHS-7.htm (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Nations, U. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2015/12/sustainable-development-goals-kick-off-with-start-of-new-year/ (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- McClintock, H.; Alber, J.M.; Schrauben, S.J.; Mazzola, C.M.; Wiebe, D.J. Constructing a measure of health literacy in Sub-Saharan African countries. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 35, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guure, C.; Owusu, S.; Dery, S.; da-Costa Vroom, F.B.; Afagbedzi, S. Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS among Ghanaian Adults from 1998 to 2014: A Multilevel Logistic Regression Model Approach. Scientifica 2020, 2020, 7313497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinamene, O.; Maria do Rosário, M.; Rita, C.; Lemuel, C.; Maria Rosalina, B.; Maria Antónia, N.; Filomena, P. Seropositivity rate and sociodemographic factors associated to HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis among parturients from Irene Neto Maternity of Lubango city, Angola. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2020, 96, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yefimenko, L.; Gasparinho, C.; Lopes, Â.; Castro, R.; Pereira, F. Treponema pallidum infection rate in patients attending the general hospital of Benguela, Angola. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2023, 17, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirwa, G.C. “Who knows more, and why?” Explaining socioeconomic-related inequality in knowledge about HIV in Malawi. Sci. Afr. 2020, 7, e00213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassana, B.Y.; Bashir, A.Y. Socio-ecological predictors of HIV testing in women of childbearing age in Nigeria. PAMJ 2022, 41, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruskin, S. The UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS: Were some lessons of the last 20 years ignored? Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenny, A.P.; Crentsil, A.O.; Asuman, D. Determinants and distribution of comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge in Ghana. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2017, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngadaya, E.; Kimaro, G.; Kahwa, A.; Mnyambwa, N.P.; Shemaghembe, E.; Mwenyeheri, T.; Wilfred, A.; Mfinanga, S.G. Knowledge, awareness and use of HIV services among the youth from nomadic and agricultural communities in Tanzania. Public Health Action 2021, 11, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, M.; Mutonyi, H. Literacy in Rural Uganda: The Critical Role of Women and Local Modes of Communication. Diaspora Indig. Minor. Educ. 2010, 1, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S.; Bishwajit, G.; Danhoundo, G.; Seydou, I. Extent of Knowledge about HIV and Its Determinants among Men in Bangladesh. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Arya, M.; Viswanath, K. Effect of Media Use on HIV/AIDS-Related Knowledge and Condom Use in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofoluwaso Bankole, O.; Abioye, A. Influence of Access to HIV/AIDS Information on the Knowledge of Federal University Undergraduates in Nigeria. Libri 2018, 68, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.M.; Sule, G.M. Media Campaign Exposure and HIV/AIDS Prevention: 1980–2020. In AIDS Updates–Recent Advances and New Perspectives; Okware, S.I., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Adams, S. Electricity access, human development index, governance and income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, C.D.; Tesema, G.A. Effect of mass media on comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS and its spatial distribution among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: A spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents (n = 19,785) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Categories | Weighted Frequency | Weighted Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 5418 | 27.4 |

| Female | 14,360 | 72.6 | |

| Age groups | 15–19 | 4925 | 24.9 |

| 20–24 | 4070 | 20.6 | |

| 25–29 | 3364 | 17 | |

| 30–34 | 2394 | 12 | |

| 35–39 | 2021 | 10 | |

| 40–44 | 1698 | 8.6 | |

| 45–49 | 1311 | 6.6 | |

| Marital status | Not married | 17,436 | 88.1 |

| Married | 2349 | 11.9 | |

| Residence | Urban | 13,916 | 70.3 |

| Rural | 5869 | 29.7 | |

| Region | Cabinda | 481 | 2.4 |

| Bengo | 225 | 1.1 | |

| Zaire | 414 | 2.1 | |

| Uíge | 965 | 4.9 | |

| Luanda | 7828 | 39.6 | |

| Cuanza Norte | 229 | 1.2 | |

| Cuanza Sul | 1355 | 6.8 | |

| Malange | 616 | 3.1 | |

| Lunda Norte | 485 | 2.5 | |

| Lunda Sul | 312 | 1.6 | |

| Benguela | 1608 | 8.1 | |

| Huambo | 1271 | 6.4 | |

| Bié | 795 | 4 | |

| Moxico | 350 | 1.8 | |

| Huíla | 1574 | 8 | |

| Namibe | 245 | 1.2 | |

| Cuando Cubango | 329 | 1.7 | |

| Cunene | 703 | 3.6 | |

| Education | Complete primary and more | 13,116 | 66.3 |

| Incomplete primary | 6669 | 33.7 | |

| Radio | At least once a week | 5826 | 29.4 |

| Less than once a week | 6173 | 31.2 | |

| Not at all | 7786 | 39.4 | |

| Television | At least once a week | 9589 | 48.5 |

| Less than once a week | 3859 | 19.5 | |

| Not at all | 6336 | 32 | |

| Journals and magazines | At least once a week | 1617 | 8.2 |

| Less than once a week | 4802 | 24.3 | |

| Not at all | 6547 | 33.1 | |

| Language spoken at home | Portuguese | 14,171 | 71.6 |

| Local languages | 5614 | 28.4 | |

| Variables | Categories | Chi-Square Analysis | Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Frequency (N = 19,785 | Weighted Percentage (%) | Crude OR (CI 95%) | Adjusted OR (CI 95%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 2989 | 55.2 | 1.51 (1.42–1.61) | 0.90 (0.91–1.07) |

| Female | 6449 | 44.9 | ref | ref | |

| Age groups | 15–19 | 2439 | 49.5 | 1.34 (1.21–1.54) | 0.93 (0.79–1.11) |

| 20–24 | 1995 | 49 | 1.34 (1.18–1.51) | 0.913 (0.76–1.09) | |

| 25–29 | 1961 | 50.3 | 1.40 (1.24–1.60) | 1.04 (0.86–1.25) | |

| 30–34 | 1152 | 48.1 | 1.29 (1.12–1.47) | 1.14 (0.93–1.38) | |

| 35–39 | 903 | 44.7 | 1.12 (0.98–1.29) | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | |

| 40–44 | 710 | 41.8 | 1.000 (0.86–1.16) | 0.95 (0.77–1.18) | |

| 45–49 | 548 | 41.8 | ref | ref | |

| Marital status | Not married | 8433 | 48.4 | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) |

| Married | 1005 | 42.8 | ref | ref | |

| Residence * | Urban | 8236 | 59.2 | 5.63 (5.24–6.05) | 1.51 (1.34–1.71) |

| Rural | 1202 | 20.5 | ref | ref | |

| Education * | Completed primary education and above | 392 | 55 | 2.44 (2.30–2.60) | 1.83 (1.67–2.00) |

| Did not complete primary education | 94 | 33.3 | ref | ref | |

| Radio | More than once a week | 176 | 62.5 | 3.51 (3.27–3.77) | 1.09 (0.97–1.21) |

| At least once a week | 241 | 53.2 | 2.39 (2.23–2.56) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) | |

| Not at all | 5593 | 32.2 | ref | ref | |

| Television * | More than once a week | 99 | 67.7 | 8.35 (7.74–8.99) | 2.40 (2.11–2.72) |

| At least once a week | 334 | 43.3 | 3.04 (2.78–3.32) | 1.32 (1.16–1.52) | |

| Not at all | 202 | 20.1 | ref | ref | |

| Newspapers and magazines * | More than once a week | 170 | 77.9 | 3.47 (3.06–3.94) | 1.99 (1.73–2.30) |

| At least once a week | 107 | 69.9 | 2.29 (2.12–2.43) | 1.626 (1.49–1.77) | |

| Not at all | 456 | 50.3 | ref | ref | |

| Language spoken at home * | Portuguese | 258 | 57.5 | 4.53 (4.22–4.86) | 1.39 (1.24–1.56) |

| Local languages | 100 | 23 | ref | ref | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos, N.N.V.; Fronteira, I.; Martins, M.d.R.O. Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS and Related Factors in Angolans Aged between 15 and 49 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196816

Ramos NNV, Fronteira I, Martins MdRO. Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS and Related Factors in Angolans Aged between 15 and 49 Years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(19):6816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196816

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos, Neida Neto Vicente, Inês Fronteira, and Maria do Rosário O. Martins. 2023. "Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS and Related Factors in Angolans Aged between 15 and 49 Years" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 19: 6816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196816

APA StyleRamos, N. N. V., Fronteira, I., & Martins, M. d. R. O. (2023). Comprehensive Knowledge of HIV and AIDS and Related Factors in Angolans Aged between 15 and 49 Years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(19), 6816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196816