Abstract

Although a recording and reporting format for health centers already exists for Indonesia’s standard information system, numerous health applications still need to meet the needs of each program. Therefore, this study aimed to demonstrate the potential disparities in information systems in the application and data collection of health programs among Indonesian community health centers (CHCs) based on provinces and regions. This cross-sectional research used data from 9831 CHCs from the Health Facilities Research 2019 (RIFASKES). Significance was assessed using a chi-square test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). The number of applications was depicted on a map using the spmap command with STATA version 14. It showed that region 2, which represented Java and Bali, was the best, followed by regions 1, which comprised Sumatra Island and its surroundings, and 3, Nusa Tenggara. The highest mean, equaling that of Java, was discovered in three provinces of region 1, namely, Jambi, Lampung, and Bangka Belitung. Furthermore, Papua and West Papua had less than 60% for all types of data-storage programs. Hence, there is a disparity in the health information system in Indonesia by province and region. The results of this analysis recommend future improvement of the CHCs’ information systems.

1. Introduction

The established health system needs a robust health information system. One measure of its success is equitable distribution. In the current era of digitalization, there are demands for data to be brought together for both individuals and health facilities [1,2,3]. The availability of data and good monitoring enhance their utilization. Hence, they can replace population-based surveys [4].

Data in health facilities of developed countries are inputted electronically, either online or offline. However, in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs), entry of health data, especially for primary services, is not adequate [3,5]. Furthermore, other problems include the use of various applications, varied program data requirements, and poor data quality. This is due to lack of monitoring and evaluation of the information system used [6].

Previous research on Indonesian health information systems has covered hospital information systems, electronic medical records, information systems, mHealth, e-health, telemedicine, and the primary healthcare information system (SIMPUS) [7]. Conversely, in developed countries, research on health information systems has included software, artificial intelligence, clinical decision support systems (clinical DSSs), epidemiological monitoring, data mining, patient safety and outcomes, meaningful use, quality improvement, and social media [8].

As one of the LMICs, Indonesia has a diverse primary care information system. Despite a standard information system already being in place—namely, the existence of records and reports known as the Puskesmas (community health centers) Management Information System (SIMPUS), and all its versions—many health programs, such as maternal, dengue, and other ones, have unique applications [6,9]. Finally, health centers do not work on only one type of system or application that contains various management, facility, and individual data. They have an additional burden of running more than 10 required programs.

The expected outcome of the current vision for data includes efficient and high-quality information. Furthermore, the ability of data entry in CHCs varies depending on the number of employees, the ability of the human resources, the electronic devices, and organizational support, such as the available Internet network [10]. These conditions lead to disparities between regions and provinces, which ultimately affect the health information system. This disparity is likely to occur in Indonesia because this country consists of many islands with unequal resources. By examining the existing information systems in primary health services in Indonesia, it is possible to capture the disparities that occur. Demonstrating the disparities is needed to improve health systems [11]. Therefore, this study was conducted to demonstrate the potential disparities of the health information systems in Indonesia, namely, the application and data collection of programs at the CHCs by province and region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This was an analysis of the Indonesian Health Facility Research (RIFASKES) data for 2019 [12]. The RIFASKES design is a survey. The original survey collected data on health facilities, including the characteristics of facilities, resources, management, organization, planning, supporting facilities, and information systems. Systems consisted of CHCs, hospitals, and other health facilities. Furthermore, the data of this study were related to research on CHCs. The cross-sectional design of the RIFASKES determined the total sample, namely, all the CHCs in Indonesia. The inclusion criteria were registered with the Ministry of Health data in July 2018 and verified by the local District Health Office (DHO). Furthermore, the data of this study focus on CHCs.

2.2. Time, Place, and Data Collection

Data were collected from April to May 2019 by teams of two members from five CHCs per team. Each team visited the CHC health center for four days to obtain all the survey information. The enumerator criteria were a minimum college education (Diploma III at the Department of Health), <45 years old, a non-civil servant, were currently not studying, resided in the province of the research location, applied to become an enumerator, and participated in the selection and technical research training.

Data were acquired through interviews with the program manager for the health information system at the CHC, usually the director. Enumerators performed the interviews using a standardized questionnaire. The assessed disease data application is an application installed on the CHC computer. If they had it, we asked if it was used. Additionally, the enumerators observed and searched the documents and applications. This survey did not assess the process and quality of the data.

2.3. Questionnaire

The focus of this analysis was on the CHC record system. Three main parts were analyzed: the Ministry of Health application, an application to support health insurance, and an application for health and disease programs. Questions included the availability of 13 types of records, namely: SKDR (Sistim Kewaspadaan Dini dan Respon), or Early Warning of Epidemic Diseases; ASPAK (Aplikasi Sarana Prasarana dan Alat Kesehatan), or Health Facilities and Supplies Application; PISPK (Program Indonesia Sehat Pendekatan Keluarga), or the Healthy Family Program; P Care (Primary care), a health insurance application; HFIS (Health Financing Information System), for financing of health insurance; SITT (Sistim Informasi Tuberculosis Terpadu), for tuberculosis information; SIHA (Sistim Informasi HIV AIDS), for HIV AIDS information; SIHEPI (Sistim Informasi Hepatisis), or Hepatitis Information; SIPTM (Sistim Informasi Penyakit tidak Menular), or Non Communicable Disease Information; SIPD3I (Sistim Informasi Penyakit yang Dapat Dicegah dan Diobati dengan Imunisasi), or Diseases Prevented and Cured by Immunization; ESISMAL (Electronic System oh Malaria), or Malaria Information; SISTBM (Sistim Informasi Sanitasi Total Berbasis Masyarakat), or Health Sanitation Population-Based; EPPGBM (Electronic Pencataan dan Pelaporan Gizi Berbasis Masyarakat), or Nutrition Information.

The information system owned by the CHCs included medical records and SIMPUS. This analysis excluded health program applications that were relatively new and had not been widely used, such as the dengue and mental health applications.

According to a decree issued by the regional government, criteria for CHCs were established based on urban, rural, remote, and very remote areas. Furthermore, the outpatient and inpatient criteria, accreditation status of the CHC, and financial management were determined based on the available document. Division of the territory into seven regions was performed according to the classification of Indonesia’s development areas, as written in the Medium-Term Development Plan [13]. Regions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 were provinces located on the island of Sumatra and its surroundings, Java and Bali, Nusa Tenggara, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua, respectively.

2.4. Data Management and Analysis

The data processing of RIFASKES 2019 consisted of two stages. The first was conducted in regencies/cities and consisted of data collection, receiving–batching (acceptance–bookkeeping), editing (data quality control), data entry, and sending electronic data. The second was performed in the National Institute of Health Research and Development (NIHRD). It consisted of receiving and merging data for all regencies/cities, cleaning data, merging provincial and national data, cleaning national data, imputation, weighting, and storing electronic data.

The team submitted a data request to the Repository of NIHRD, namely, the data-related health information system at a CHC. Data were tabulated, and the significance was assessed using a chi-square test. Furthermore, the number of applications was assessed for the mean, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) determined the significance. Next, data were mapped using the spmap command with STATA version 14. The categorization was based on the default STATA, which automatically divided the data into four quartiles.

3. Results

The CHCs originated from 34 provinces, which included all Indonesian districts and cities. The total CHSs was 9909. We coordinated with local DHOs before the study was implemented. As a result, 14 health centers were eliminated, since they were declared unavailable. There were 9885 CHCs visited; furthermore, 54 changed their functions during data collection, or their buildings were no longer available. Therefore, there were 9831 CHCs analyzed, and the response rate was 99.2%.

Table 1 shows the number of health centers per province. Based on that table, the majority of the CHCs, which included those with inpatient status, were located in rural areas. In Indonesia, at least 2262 health centers were not accredited. Being an unaccredited CHC implied that they had not accomplished accreditation when this research was conducted. Regarding financial management, most were non-public services (non-BLUD), which indicated that the operational funds were entirely from the local government, whereas BLUD refers to CHCs that had satisfied the requirements for some degree of financial autonomy. The highest numbers of health centers were in West and East Java, and the smallest numbers were in Bangka Belitung and North Kalimantan. Table 2 shows the number of health-center applications based on regional criteria.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the CHCs.

Table 2.

Number of applications or programs in urban, rural, and remote areas.

Table 2 shows disparities in the numbers and percentages of available health applications. In general, urban and rural areas had more health applications, except for E SISMAL, which was more widely available in rural and remotes areas—71.16% and 75.39%, respectively. This pattern was different from urban areas, which did not have many of these applications. Table 3 shows the regional division in Indonesia, which consists of seven regions.

Table 3.

Numbers and percentages of the presence of information programs based on the number of CHCs in each region in Indonesia.

Table 3 shows that many health centers in Indonesia have applications for these programs—more than 50%. Furthermore, ASPAK, PISPK, and P.care were owned by approximately 90% of health centers. As a result, there were some regions, 4, 5, 6, and 7, that had health applications. On average, the health centers had 10 information system programs (mean = 10.37 and median of 10.80). The results have been displayed in the form of a map by region.

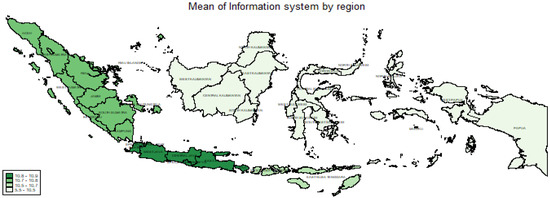

In Figure 1, the categories are divided into four quartiles, namely, areas with means of 5.5 to <10.5, 10.5 to <10.7, 10.7 to <10.8, and 10.8 to 10.9. The best areas were region 2, followed by 1 (Sumatra), and then 3 (Nusa Tenggara). Meanwhile, 4, 5, 6, and 7 were in one category, as they had means of 5.5 to <10.5.

Figure 1.

Mean presence of an information system by region.

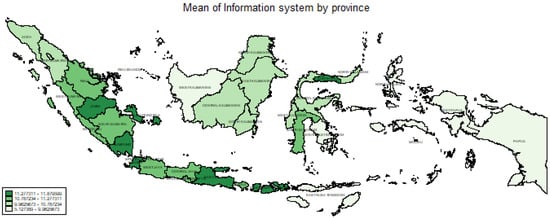

In Figure 2, the area is divided based on quartiles, namely, 5.13 to <9.96, 9.96 to <10.78, 10.78 to <11.27, and 11.27 to 11.87. It is shown that in the best region (region 2), not all provinces had a high mean of 11.27–11.87. Those with the highest mean were observed in the Banten and East Java provinces. The highest mean, that of region 1 (Sumatra Island), was discovered in the Jambi, Lampung, and Bangka Belitung provinces. Apart from regions 1 and 2, only Gorontalo Province a mean in the highest quartile. Meanwhile, only South Sulawesi Province had a high mean of 10.78 to <11.27.

Figure 2.

Mean presence of an information systems by province.

Table 4 shows the proportion of CHCs with Information Application or Program by Province. It shows that Papua and West Papua had percentages of less than 60% for all types of information application. Furthermore, Jakarta had less than 50% ownership for several programs, namely, SIHA, SIHEPI, and ESISMAL. Programs with less than 60% ownership in several provinces included SKDR, SIHA, SIHEPI, SIPD3I, and ESISMAL. However, there was no SKDR ownership of more than 90%. Many provinces had below 70% ownership of HFIS, even though this was mandatory for the national health insurance provider. The same was true for SIHA and SIHEPI, many of which still had SIPD3I percentages below 70%.

Table 4.

Proportion of CHCs with Information Application or Program by Province.

4. Discussion

The analysis showed disparities between the regions and provinces regarding the number of applications and data collection of health programs. Figure 1 indicates that the eastern part of Indonesia is significantly different from the western part. The central part was almost the same as eastern Indonesia regarding the average number of applications owned. Furthermore, some provinces had a small average of applications or programs compared to others. This is common in LMICs where the health information systems are strongly influenced by human-resource factors, institutional funding, foreign aid, corruption, transparency, and poor priorities [5,14].

The province of Jakarta, where the capital city is located, had an average number of applications or health programs which was not high compared to other provinces on the island of Java. Although this has never been analyzed, it is possible, since the CHCs in Jakarta are different from those in other regions. For example, the CHCs in this province are located almost exclusively in sub-districts (kelurahan). However, they are independent in their work and not branch of the CHCs in some large sub-district [15]. Therefore, many sub-districts’ CHCs did not have information-system programs, since they shared tasks with sub-district health centers. Another explanation is that Jakarta was not an endemic area for diseases such as malaria; hence, the use of ESISMAL was deficient, at approximately 25%. In contrast to the disparity problem in eastern Indonesia, there are issues pertaining to the availability of PCs, the electricity supply, workforce availability and their skills, Internet access, etc.

This disparity in one part of the health information system causes various problems. The primary issue is interoperability with security and intellectual property [1,14,16,17,18]. The poor implementation is caused by the absence of monitoring or evaluation [6,19]. Furthermore, its evaluation is complex in many countries, since there are no tools available to assess them, unlike the information system in the maternal sector, which has the MADE IN/OUT method for evaluation [9].

A system for recording health and disease programs can replace extensive surveys and provide good-quality data [4]. They are used in research, even for randomized clinical trials [2,20]. Additionally, some health facilities use information systems capable of diagnosing diseases [21]. Their implementation is related to the competence of human resources and updating programs or applications [22,23,24,25]. However, a lack of human resources and not being consistent with the number of patients will cause the system to not work well and produce poor-quality data [23,25,26].

Support from the government is required to improve the implementation of the health information system [4,27]. The disparities in the health sector among regions in Indonesia exist in the utilization of health facilities, not only in the information system alone [28]. According to the regulation of Minister of Health Number 97 in 2015, the government emphasized the procurement of data on health facilities, data flow, and access. Hence, the problem of interoperability and data quality was not a significant issue [1].

Furthermore, many things should be considered in the health information system, such as electronic medical records, and integration or bridging with other data, especially with population identity data, as attempted in Brazil [17,29], including system modifications for certain groups [30].

A limitation of this research was the absence of an evaluation in the implementation process and the quality of the data output. Furthermore, not all information systems in health centers were assessed, such as medical records, or CHC information systems, such as SIMPUS. In contrast, the inclusion of national data from all CHCs registered in the Health Service and the Ministry of Home Affairs would require a great effort and an enormous cost.

Based on the disparities shown through the results of this study, it is necessary to strengthen the health system in the form of surveillance of data and more significant support from the provincial and district levels to CHCs to ensure the uploading and operation of the required applications. Another suggestion is that the government should be expected to evaluate the information systems of the CHCs, especially regarding data entry for disease-based health programs.

Additionally, interoperability capabilities, deployment of human resources, and updating the system according to the current situation should also be monitored continuously.

Disease data applications involve the digitalization of disease records. The deployment of digital systems requires well-designed applications, supporting and changing management, and strengthening human resources to realize and sustain system health gains [31]. This process does not just happen, but begins with digitization and digital transformation [32]. Nowadays, the digitalization of the system has become an important determinant [33].

5. Conclusions

This analysis showed disparities in the health information system in Indonesia by province and region. For example, although the islands of Java, Bali, and Sumatra had attractive situations when broken down, some provinces had poor information systems in their CHCs regarding availability and the number of applications or data-storage programs used. The results of this analysis recommend future improvement of the CHCs’ information systems. The gap between the western and the eastern parts of Indonesia needs to be overcome by increasing resources, including human resources and supportive management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I. and H.H.; methodology S.I. and H.H.; formal analysis, S.I. and M.H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I.; writing—review and editing, S.I. and M.H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study used the National Survey Data funded by the Indonesian government through Ministry of Health budget (APBN).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Commission of the National Institute of Health Research and Development (NIHRD) of Ministry of Health, number LB.02.01/2/KE.318/2018, and amendment number: LB.02.01/2/KE.011/2019.

Informed Consent Statement

All methods were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and all its future amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interviews.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical reasons but are available upon request from the Director of the NIHRD, which has now been renamed the Health Policy Agency of Ministry of Health Indonesia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Director General of the NIHRD of Ministry of Health Indonesia for granting access to the data. The authors are also grateful for the data management team for providing the dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wardhani, V.; Mathew, S.; Seo, J.-W.; Wiryawan, K.G.; Setiawaty, V.; Badrakh, B. Why and how do we keep editing local medical journals in an era of information overload? Sci. Ed. 2018, 5, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yang, G.; Li, D.; Wang, L.; Tang, L. Changing antibiotic prescribing practices in outpatient primary care settings in China: Study protocol for a health information system-based cluster-randomised crossover controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0259065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higman, S.; Dwivedi, V.; Nsaghurwe, A.; Busiga, M.; Sotter Rulagirwa, H.; Smith, D.; Wright, C.; Nyinondi, S.; Nyella, E.; Nsaghurwe, A.; et al. Designing interoperable health information systems using Enterprise Architecture approach in resource-limited countries: A literature review. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 34, e85–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Bergen, N.; Schlotheuber, A.; Boerma, T. National health inequality monitoring: Current challenges and opportunities. Glob. Health Action 2018, 11, 1392216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.C. Contextual factors affecting health information system strengthening. Glob. Public Health 2017, 12, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faridah, L.; Rinawan, F.R.; Fauziah, N.; Mayasari, W.; Dwiartama, A.; Watanabe, K. Evaluation of Health Information System (HIS) in The Surveillance of Dengue in Indonesia: Lessons from Case in Bandung, West Java. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watsiq, A.; Madjido, M.; Espressivo, A.; Watsiq Maula, A.; Fuad, A.; Hasanbasri, M. Health Information System Research Situation in Indonesia: A Bibliometric Analysis ScienceDirect Health Information System Research Situation in Indonesia: A Bibliometric Analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Wang, S.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, X.; Kim, H.-E.; Sun, J.; Ohno-Machado, L. Trends in biomedical informatics:automated topic analysis of JAMA articles. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qomariyah, S.N.; Sethi, R.; Izati, Y.N.; Rianty, T.; Latief, K.; Zazri, A.; Besral; Bateman, M.; Pawestri, E.A.; Ahmed, S.; et al. No one data source captures all: A nested case-control study of the completeness of maternal death reporting in Banten Province, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, N.C.; Handayani, P.W.; Hidayanto, A.N. Barriers in Health Information Systems and Technologies to Support Maternal and Neonatal Referrals at Primary Health Centers. Healthc Inform. Res. 2021, 27, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hailu, B.; Tabor, D.C.; Gold, R.; Sayre, M.H.; Sim, I.; Jean-Francois, B.; Casnoff, C.A.; Cullen, T.; Thomas, V.A.; et al. Role of Health Information Technology in Addressing Health Disparities: Patient, Clinician, and System Perspectives. Med. Care 2019, 57, S115–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.Z. Numerical study of heat and mass transfer in an enthalpy exchanger with a hydrophobic-hydrophilic composite membrane core. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2005, 51, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of National Development of Planning Indonesia. Buku III RPJMN 2015–2019. 2014, Volume 58, pp. 7250–7257. Available online: http://stranasrr.bappenas.go.id/web/assets/web/file_article/document/ (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Afrizal, S.H.; Handayani, P.W.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Eryando, T.; Budiharsana, M.; Martha, E. Barriers and challenges to Primary Health Care Information System (PHCIS) adoption from health management perspective: A qualitative study. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2019, 17, 10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinas Kesehatan, Puskesmas. Available online: https://www.jakarta.go.id/puskesmas (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Nsaghurwe, A.; Dwivedi, V.; Ndesanjo, W.; Bamsi, H.; Busiga, M.; Nyella, E.; Massawe, J.V.; Smith, D.; Onyejekwe, K.; Metzger, J.; et al. One country’s journey to interoperability: Tanzania’s experience developing and implementing a national health information exchange. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, G.; Neto, C.; Neto, G.C.C.; Andreazza, R.; Chioro, A. Integration among national health information systems in Brazil: The case of e-SUS Primary Care. Rev. Saúde Pública 2021, 55, S1518–S8787. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, A.; Anderson, M.; Albala, S.; Casadei, B.; Dean Franklin, B.; Richards, M.; Taylor, D.; Tibble, H.; Mossialos, E. Health information technology and digital innovation for national learning health and care systems. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e383–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami Andargoli, A.; Scheepers, H.; Rajendran, D.; Sohal, A. Health information systems evaluation frameworks: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 97, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, D.; López-Jiménez, T.; Cos-Claramunt, X.; Ortega, Y.; Duarte-Salles, T. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer: A study protocol of case-control study using data from the Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP) in Catalonia. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.P.; Kang, D.; Houck, J. Can Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS) measures accurately enhance understanding of acceptable symptoms and functioning in primary care? J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2020, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, C.; Yakob, B.; Tilahun, T.; Nigatu, T.G.; Dinsa, G.; Woldie, M.; Kassa, M.; Berman, P.; Kruk, M.E. Patient volume and quality of primary care in Ethiopia: Findings from the routine health information system and the 2014 Service Provision Assessment survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnew, E.; Woreta, S.A.; Shiferaw, A.M. Routine health information utilization and associated factors among health care professionals working at public health institution in North Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S.T.; Georgiou, A.; Marin, H. Evaluation of Digital Health & Information Technology in Primary Care. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 144, 104285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiferaw, A.M.; Zegeye, D.T.; Assefa, S.; Yenit, M.K. Routine health information system utilization and factors associated thereof among health workers at government health institutions in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshkohan, A.; Alimoradi, M.; Ahmadi, M.; Alipour, J. Data quality and data use in primary health care: A case study from Iran. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 28, 100855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumamba, A.P.; Bisvigou, U.J.; Ngoungou, E.B.; Diallo, G. Health information systems in developing countries: Case of African countries. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyanto, J.; Kunst, A.E.; Kringos, D.S. Geographical inequalities in healthcare utilisation and the contribution of compositional factors: A multilevel analysis of 497 districts in Indonesia. Health Place 2019, 60, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Bellucci, E.; Nguyen, L.T. Electronic health records implementation: An evaluation of information system impact and contingency factors. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, T.; Flowers, J.; Sequist, T.D.; Hays, H.; Biondich, P.; Laing, M.Z. Envisioning health equity for American Indian/Alaska Natives: A unique HIT opportunity. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2019, 26, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrat, T.; Chandir, S.; Alland, K.; Pedrana, A.; Shah, M.T.; Footitt, C.; Snyder, J.; Ratanaprayul, N.; Siddiqi, D.A.; Nazneen, N.; et al. Digitalization of routine health information systems: Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan. Bull. World Health Organ. 2022, 100, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyamu, I.; Xu, A.X.T.; Gómez-Ramírez, O.; Ablona, A.; Chang, H.J.; Mckee, G.; Gilbert, M. Defining digital public health and the role of digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation: Scoping review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e30399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health, T.L.D. Digital technologies: A new determinant of health. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).