Our Healthy Community Conceptual Framework and Intervention Model for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Municipalities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Health Promotion and Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases

1.2. Our Healthy Community

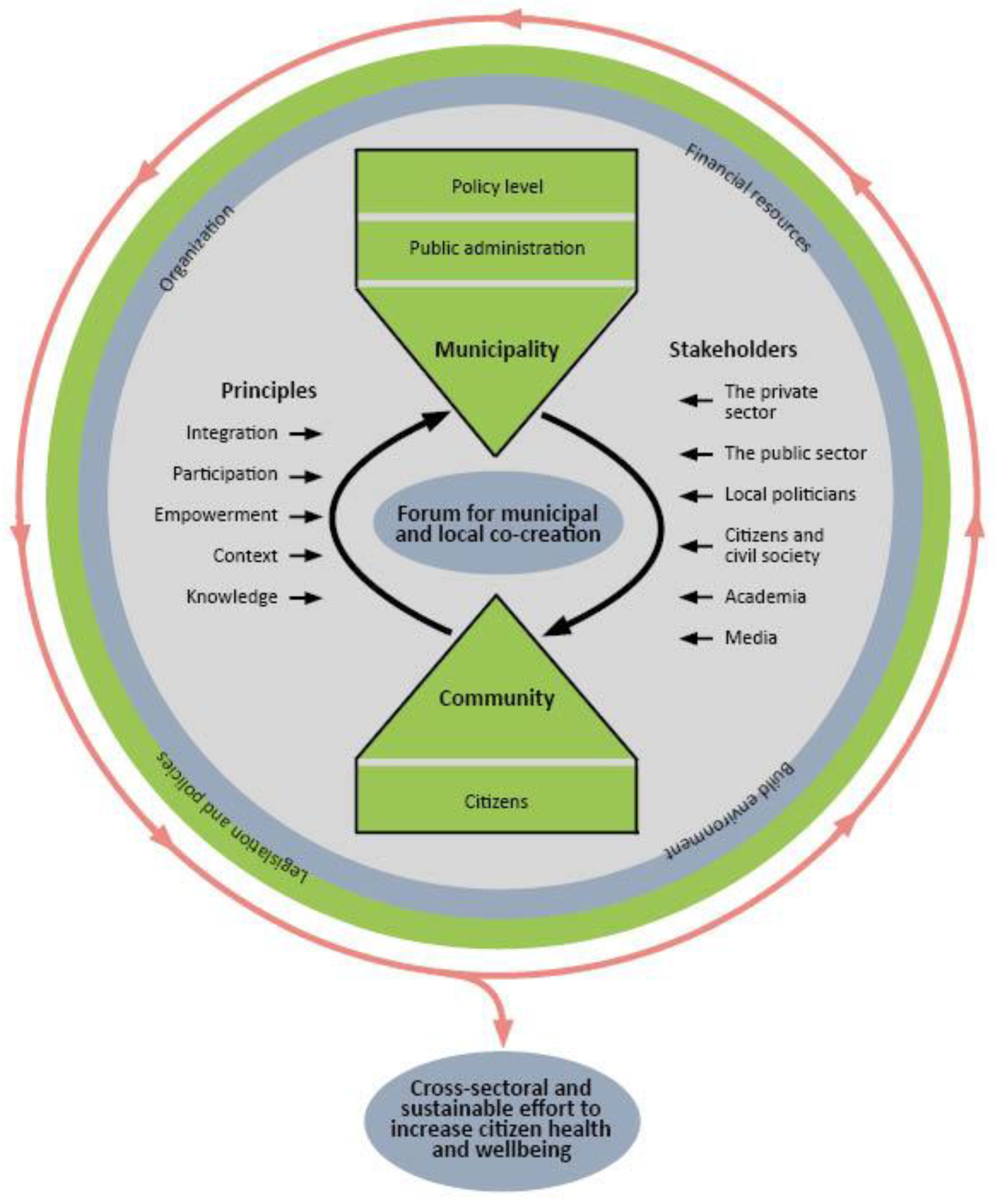

2. The Conceptual Framework

2.1. The Supersetting Approach

2.2. Systems-Based Approaches and Change Models

3. The Conceptual Model

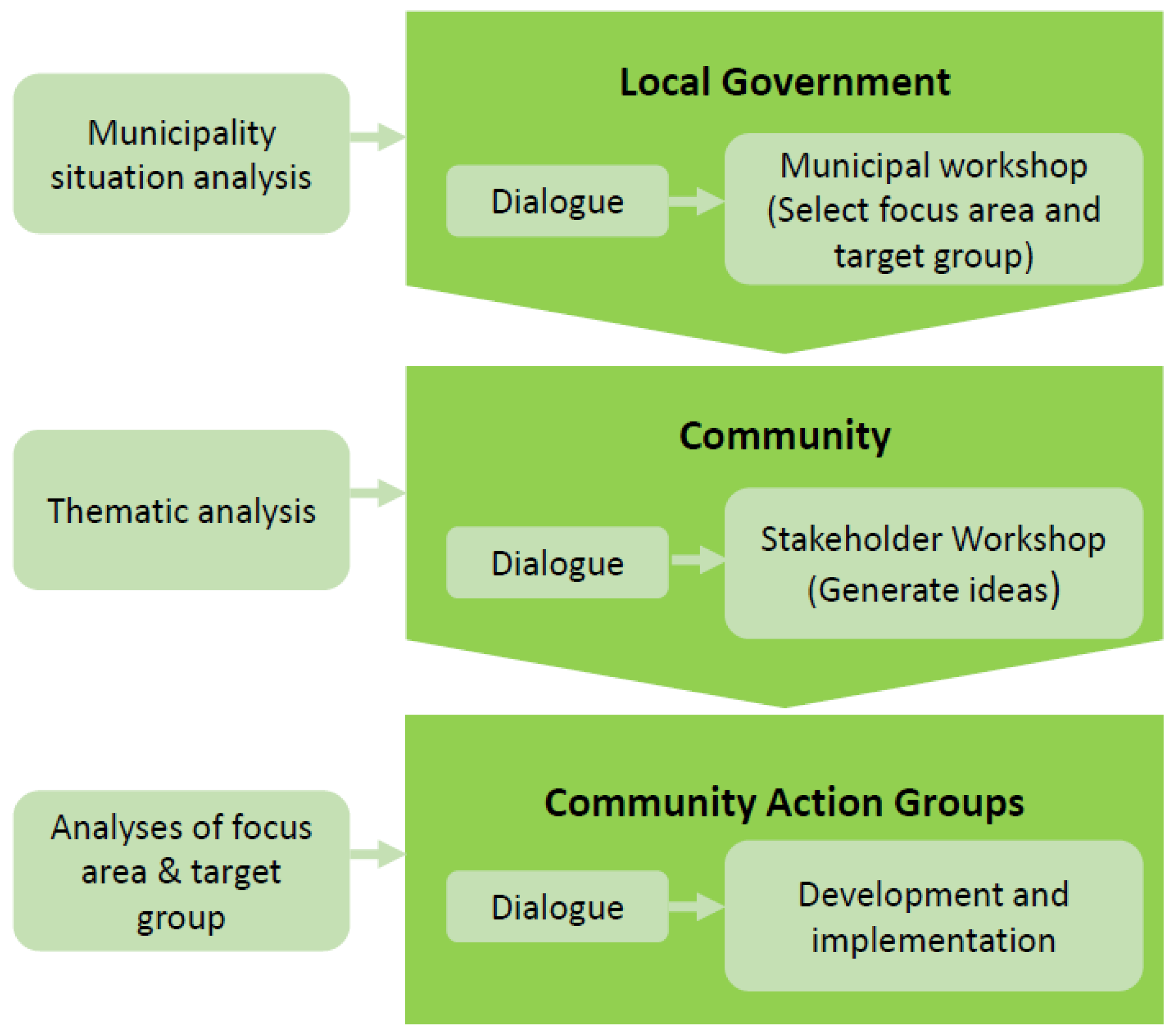

4. The Operational Intervention Model

- Phase 1. Local Government: Situational Analysis, Dialogue, and Political Priorities

- A detailed municipality situational analysis of prevailing conditions, resources, and challenges at the municipality level is carried out by project staff. This is undertaken to establish a solid knowledge base for informed decision-making in local government. The analysis includes an extensive analysis of socio-demography, health status, and lifestyle among citizens in the municipality, the organization of health systems and services, as well as existing health promotion and disease prevention initiatives in the municipality. It is mainly based on data from the National Health Profile survey [1]. In Denmark, the National Health Profile survey is carried out as a representative questionnaire-based survey within the adult population in all municipalities every four years (2013, 2017, 2021, etc.). The Municipality Situational Analysis is also based on data and information from other sources, surveys, and projects addressing health conditions, lifestyle, and well-being of citizens at the municipality level, including surveys among children, if available.

- A series of dialogue meetings are held between project staff or project representatives and relevant managers, leaders, and senior staff members in all local municipality administration departments. This is undertaken to present and talk about the project with decision-makers who may or may not consider the core functions of their department to relate to health promotion and disease prevention. The meetings are also held to gain knowledge on the tasks and duties of the departments from the perspective of decision-makers and how this relates to health, if at all. Each dialogue meeting involves a project researcher, the local project coordinator, and 2–5 public officials. It is concluded by an invitation to the department to participate in a subsequent workshop for all high-level decision-makers in the public administration and local government.

- A municipal workshop is organized for all high-level department representatives, directors, and elected council members in local government. The primary objective of this workshop is for the public administration and local government to jointly identify a thematic focus area and a primary target group for subsequent preventive intervention. Secondary objectives are for participants to become familiar with each other, to jointly discuss health as an intersectoral issue, and to establish a conducive environment in the administration for interacting and working together across departments and sectors. The workshop is of 3–4 h duration and is organized and facilitated jointly by project staff and core partners in the public administration. Facilitation is supported by various resources including an extract of data from the municipality situational analysis and a summary of the deliberations from the dialogue meetings. Methodologically, the workshop is inspired by “the search conference” approach [48] and includes group work on processes of co-creation, discussion, negotiation, and consensus building among participants.

- Phase 2. Community: Thematic Co-Creation among Professional Stakeholders

- D.

- A detailed thematic analysis of social, structural, organizational, and health-related conditions in the municipality that are directly related to the thematic focus area and primary target group for intervention is carried out by project staff. This is conducted to inform the process of bringing the selected focus areas into action. The analysis includes a mapping of relevant stakeholder organizations, physical structures, settings, and environments in the municipality. It also includes an analysis of health and social data from the municipality regarding the specific health topic that has been prioritized for intervention. Finally, the analysis includes evidence of effective solutions obtained from the scientific literature or from other publications presenting findings from projects and initiatives carried out in Denmark or elsewhere.

- E.

- A series of dialogue meetings are held between project staff, representatives from organizations, institutions, and associations from the public sector, the private sector, and the civil society in the municipality. This is undertaken to present and discuss the project with key community-based stakeholders and to understand their perspectives, priorities, and interests in joining the project and contributing to the development and implementation of project interventions at community level. Each dialogue meeting involves a project researcher, the local project coordinator, and 1–3 stakeholder representatives. It is concluded by an invitation to the stakeholder organization to participate in a subsequent workshop for all relevant community-based stakeholders in the municipality.

- F.

- A stakeholder workshop is organized for representatives from all community-based stakeholder organizations in the municipality who are interested and considered relevant to the thematic focus area and primary target group of the intervention. Eligibility and relevance of stakeholders are determined by core partners in the public administration of the municipality. The primary objective of the workshop is to identify a variety of specific ideas and topics for action within the model of the given thematic focus area and primary target group. Secondary objectives are for participants to get to know each other, to jointly discuss health as an intersectoral issue, and to commence the establishment of a relationship for interacting and working together across organizations and sectors. The workshop is of 3–4 h duration and is organized and facilitated jointly by project staff and core partners in the public administration. Facilitation is supported by various resources including an extract of data from the thematic analysis, a summary of deliberations from the dialogue meetings with stakeholders, and a geographical GIS map of the municipality. Methodologically, the workshop is inspired by “the search conference” approach [36] and includes group work on processes of co-creation, discussion, negotiation, and consensus building among participants.

- Phase 3. Target Area: Intervention Development and Implementation

- G.

- Several community action groups are formed by project staff in collaboration with the local coordinator and the municipality based on the outputs of the stakeholder workshop. This is undertaken to establish relevant, intersectoral, and interorganizational partnerships to further develop and test interventions based on their joint priorities and ideas. Prior to this, project staff have reviewed the different ideas for community action that were generated at the stakeholder workshop and aligned them based on proposed topics, settings, target groups, etc. The community action groups thus comprise participants from the stakeholder workshop across public, private, and civic affiliations. New stakeholders may subsequently come onboard while others may leave, depending on the directions taken by the groups. Each community action group strives to develop and implement one or more activities or projects together with relevant citizens and population groups. The community action groups are supported and facilitated by project staff as long as necessary.

- H.

- A variety of specific activities or projects are developed and implemented by the community action groups. For a period of 4–6 months, administrative and technical support is provided to the community action groups by the local project coordinator who organizationally bridges the municipality administration and the project secretariat embedded in an academic partner institution. The project coordinator is partly or fully funded by the project or shared between the project and local government. Project staff mainly provide support to processes of developing and evaluating the activities and projects that are developed by the community action groups. This involves support to the facilitation of development processes and to the evaluation of processes and effects of the intervention. It may also involve support to conduct a contextualised analysis of the selected geographical focus area and target group. To promote synergy and increase impact, the activities and projects that are developed by the different community action groups are coordinated and integrated with each other and with other activities in the municipality. This provides circumstances for developing a coordinated and integrated intervention that is perceived as relevant, has strong local ownership, and is integrated in operations and systems of the municipality.

Key Assumptions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jensen, H.A.R.; Davidsen, M.; Ekholm, O.; Christensen, A.L. Danskernes Sundhed—Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2017; 2018. Available online: https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2018/danskernes-sundhed-den-nationale-sundhedsprofil-2017 (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) GLobal Observatory (GHO) Data. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Eurostat. Eurostat Statistics Explained. Healthcare Expenditure Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Healthcare_expenditure_statistics#Healthcare_expenditure (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Levelling up (part 2): A Discussion Paper on European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2006. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107791 (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- World Health Organization: Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ottawa-charter-for-health-promotion (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Bordieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociaology of Education; Richardson, J.D., Ed.; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Pelican, J.M. Understanding Differentiation of Health in Late Modernity by Use of Sociological Systems Theory. In Health and Modernity—The Role of Theory in Health Promotion; McQueen, D.V., Kickbusch, I., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson, T.; Kawachi, I. Behavioral economics: Merging psychology and economics for lifestyle interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, T.; Capewell, S.; Prescott, E.; Allender, S.; Sans, S.; Zdrojewski, T.; De Bacquer, D.; de Sutter, J.; Franco, O.H.; Logstrup, S.; et al. Population-level changes to promote cardiovascular health. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2013, 20, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Afshin, A.; Benowitz, N.L.; Bittner, V.; Daniels, S.R.; Franch, H.A.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Kraus, W.E.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Krummel, D.A.; et al. Population approaches to improve diet, physical activity, and smoking habits: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012, 126, 1514–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosse, E. National objectives—Local practice: Implementation of health promotion policies. In An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Systems, Settings and Social Processes; Wold, B., Samdal, O., Eds.; Bentham Science: Sharjay, United Arab Emirates, 2012; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cinar, E.; Trott, P.; Simms, C. A systematic review of barriers to public sector innovation process. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 264–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundhedsloven. 2018. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2018/191 (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Ministry of Health. Healthcare in Denmark—An Overview. 2017. Available online: https://www.healthcaredenmark.dk/media/ykedbhsl/healthcare-dk.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Khalil, H.; Kynoch, K. Implementation of sustainable complex interventions in health care services: The triple C model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescud, M.; Rychetnik, L.; Allender, S.; Irving, M.J.; Finegood, D.T.; Riley, T.; Ison, R.; Rutter, H.; Friel, S. From Understanding to Impactful Action: Systems Thinking for Systems Change in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems 2021, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, H.; Savona, N.; Glonti, K.; Bibby, J.; Cummins, S.; Finegood, D.T.; Greaves, F.; Harper, L.; Hawe, P.; Moore, L.; et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 2017, 390, 2602–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, L.; McQueen, D.V. Modernity, Public Health and Health Promotion: A reflexive Discourse. In Health and Modernity—The Role of Theory in Health Promotion; McQueen, D.V., Kickbusch, I., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, P.; Toft, U.; Reinbach, H.C.; Clausen, L.T.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Poulsen, K.; Jensen, B.B. Revitalizing the setting approach—Supersettings for sustainable impact in community health promotion. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 2014, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, B.E.; Bloch, P.; Reinbach, H.C.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Lawaetz Winkler, L.; Toft, U.; Glumer, C.; Jensen, B.B.; Aagaard-Hansen, J. Project SoL-A Community-Based, Multi-Component Health Promotion Intervention to Improve Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Practices among Danish Families with Young Children Part 2: Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft, U.; Bloch, P.; Reinbach, H.C.; Winkler, L.L.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Aagaard-Hansen, J.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Jensen, B.B.; Glumer, C. Project SoL-A Community-Based, Multi-Component Health Promotion Intervention to Improve Eating Habits and Physical Activity among Danish Families with Young Children. Part 1: Intervention Development and Implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toft, U.; Andersen, T.B.; Bloch, P.; Winkler, L.L.; Glumer, C. The Quantitative evaluation of the Health and Local Community Project (SoL). Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniszewska, S. Patient and public involvement in health services and health research: A brief overview of evidence, policy and activity. J. Res. Nurs. 2009, 14, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, L.; Caplan, J.; Ben-Moshe, K.; Dillon, L. Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments; American Public Health Association and Public Health Institute: Washington, DC, USA; Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G.F.; Evans, R.E.; Hawkins, J.; Littlecott, H.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Bonell, C.; Murphy, S. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: Future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Evaluation 2019, 25, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall, A.M.; Radley, D.; Jones, R.; Gately, P.; Nobles, J.; Van Dijk, M.; Blackshaw, J.; Montel, S.; Sahota, P. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramante, C.T.; Thornton, R.L.J.; Bennett, W.L.; Zhang, A.; Wilson, R.F.; Bass, E.B.; Tseng, E. Systematic Review of Natural Experiments for Childhood Obesity Prevention and Control. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.; McGIll, E.; Penney, T.; Anderson de Cuevas, R.; Er, V.; Orton, L.C. NIHR SPHR Guidance on Systems Approaches to Local Public Health Evaluation. Part 2: What to Consider when Planning a Systems Evaluation. National Institute for Health Research School for Public Health Research, London. 2019. Available online: https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NIHR-SPHR-SYSTEM-GUIDANCE-PART-2-v2-FINALSBnavy.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Egan, M.; McGIll, E.; Penney, T.; Anderson de Cuevas, R.; Er, V.; Orton, L.C. NIHR SPHR Guidance on Systems Approaches to Local Public Health Evaluation. Part 1: Introducing Systems Thinking; National Institute for Health Research School for Public Health Research, London. 2019. Available online: https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NIHR-SPHR-SYSTEM-GUIDANCE-PART-1-FINAL_SBnavy.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Soparnot, R. The concept of organizational change capacity. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2011, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperrider, D.L.; Whitney, D.; Stavros, J. Appreciative Inquiry Handbook, for Leaders of Change; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Quinn, R.E. Organizational change and development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Wold, B.; Samdal, O. The ecology of Health Promotion. In An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Systems, Settings and Social Processes; Wold, B., Samdal, O., Eds.; Bentham Science: Sharjay, United Arab Emirates, 2012; pp. 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Nowell, B.; Yang, H. Putting the system back into systems change: A framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, J.F.; Egilstrod, B.; Overgaard, C.; Petersen, K.S. Public involvement in the planning, development and implementation of community health services: A scoping review of public involvement methods. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 809–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, E.J. Ecology, Wicked Problems, and the Context of Community Interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, E.J.; Schensul, J.J. Summary comments: Multi-level community based culturally situated interventions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 43, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trøndelagsmodellen for Folkehelse Arbeid. Available online: https://www.trondelagfylke.no/globalassets/dokumenter/folkehelse-idrett-og-frvillighet/folkehelse/program-for-folkehelsearbeid-i-trondelag-2017---2023/om-programmet/trondelagsmodellen-for-folkehelsearbeid.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Haynes, A.; Rowbotham, S.; Grunseit, A.; Bohn-Goldbaum, E.; Slaytor, E.; Wilson, A.; Lee, K.; Davidson, S.; Wutzke, S. Knowledge mobilisation in practice: An evaluation of the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillefjell, M.; Wist, G.; Magnus, E.; Anthun, K.S.; Horghagen, S.; Espnes, G.A.; Knudtsen, M.S. Trøndelagsmodellen; NTNU Senter for Helsefremmende Forskning: 2017. Available online: https://inherit.eu/wp-content/uploads/pdf/The%20Trondelag%20Model.pdf. (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Thorlindsson, T.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Roe, K.M.; Allegrante, J.P. Substance use prevention for adolescents: The Icelandic Model. Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterlander, W.E.; Luna Pinzon, A.; Verhoeff, A.; den Hertog, K.; Altenburg, T.; Dijkstra, C.; Halberstadt, J.; Hermans, R.; Renders, C.; Seidell, J.; et al. A System Dynamics and Participatory Action Research Approach to Promote Healthy Living and a Healthy Weight among 10-14-Year-Old Adolescents in Amsterdam: The LIKE Programme. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization and Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Health in All Policies: Helsinki Statement. Framework for Country Action. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506908 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Baum, F.; Delany-Crowe, T.; MacDougall, C.; Lawless, A.; van Eyk, H.; Williams, C. Ideas, actors and institutions: Lessons from South Australian Health in All Policies on what encourages other sectors’ involvement. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delany, T.; Lawless, A.; Baum, F.; Popay, J.; Jones, L.; McDermott, D.; Harris, E.; Broderick, D.; Marmot, M. Health in All Policies in South Australia: What has supported early implementation? Health Promot. Int. 2016, 31, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, E.; Knudtsen, M.S.; Wist, G.; Weiss, D.; Lillefjell, M. The Search Conference as a Method in Planning Community Health Promotion Actions. J. Public Health Res. 2016, 5, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aadahl, M.; Vardinghus-Nielsen, H.; Bloch, P.; Jørgensen, T.S.; Pisinger, C.; Tørslev, M.K.; Klinker, C.D.; Birch, S.D.; Bøggild, H.; Toft, U. Our Healthy Community Conceptual Framework and Intervention Model for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Municipalities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053901

Aadahl M, Vardinghus-Nielsen H, Bloch P, Jørgensen TS, Pisinger C, Tørslev MK, Klinker CD, Birch SD, Bøggild H, Toft U. Our Healthy Community Conceptual Framework and Intervention Model for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Municipalities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053901

Chicago/Turabian StyleAadahl, Mette, Henrik Vardinghus-Nielsen, Paul Bloch, Thea Suldrup Jørgensen, Charlotta Pisinger, Mette Kirstine Tørslev, Charlotte Demant Klinker, Signe Damsbo Birch, Henrik Bøggild, and Ulla Toft. 2023. "Our Healthy Community Conceptual Framework and Intervention Model for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Municipalities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053901

APA StyleAadahl, M., Vardinghus-Nielsen, H., Bloch, P., Jørgensen, T. S., Pisinger, C., Tørslev, M. K., Klinker, C. D., Birch, S. D., Bøggild, H., & Toft, U. (2023). Our Healthy Community Conceptual Framework and Intervention Model for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Municipalities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053901