A Human-Centered Design Approach to Develop Oral Health Nursing Interventions in Patients with a Psychotic Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Contextual Interviews

2.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Persona Construction

2.4.2. Persona Validation

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Contextual Interviews

3.1.1. The Attitudes, Perspectives, and Daily Practices of MHNs Regarding Oral Health

Because in my own experience with my bad teeth in health care, it was sometimes signalled by MHNs, but then nothing was done about it. And that is because, well, people (MHNs), do not think that is their job. And that is a wrong way of thinking.(Participant 9)

3.1.2. Barriers to Providing Oral Health Care

We have about 30 min with a patient. In that time, we also must check on medication, and symptoms. After 30 min, we should go to the next patient. There is no time for MHNs to do something with oral health.(Participant 2)

The cost of treatment of severe symptoms is too high for patients and a barrier to make an appointment. We see patients too late.(Participant 6)

In practice, at the time of intake, we know what medication patients are taking and we can respond accordingly. But if something changes in the meantime and we are not informed, it becomes difficult.(Participant 10)

3.1.3. Needs of MHNs for Providing Oral Care

I know that oral care is important, but I do not know why. Well, brushing twice a day, I think that when I have more background information and underpinning information, I will also do more with it in practice.(Participant 3)

Good communication skills are essential, because the shame and the fear of stigmatization play a crucial role, so you must be able to empathize with patients.(Participant 9)

3.1.4. Interventions for MHNs for Providing Oral Health Care

I see that also that fellow MHNs do not concern themselves with this, and when patients are admitted to an outpatient-team (e.g., early intervention psychosis team or assertive community treatment teams), no attention is paid oral health, and a somatic screening is done and patients were physically examined, except in the mouth.(Participant 3)

A digital decision app with knowledge on oral health (e.g., importance, risk factors) and an advice nurses can give to their patients (e.g., based on oral health screening) could be appropriate, like a decision tree.(Participant 10)

3.1.5. Site Conditions to Provide Oral Health Care

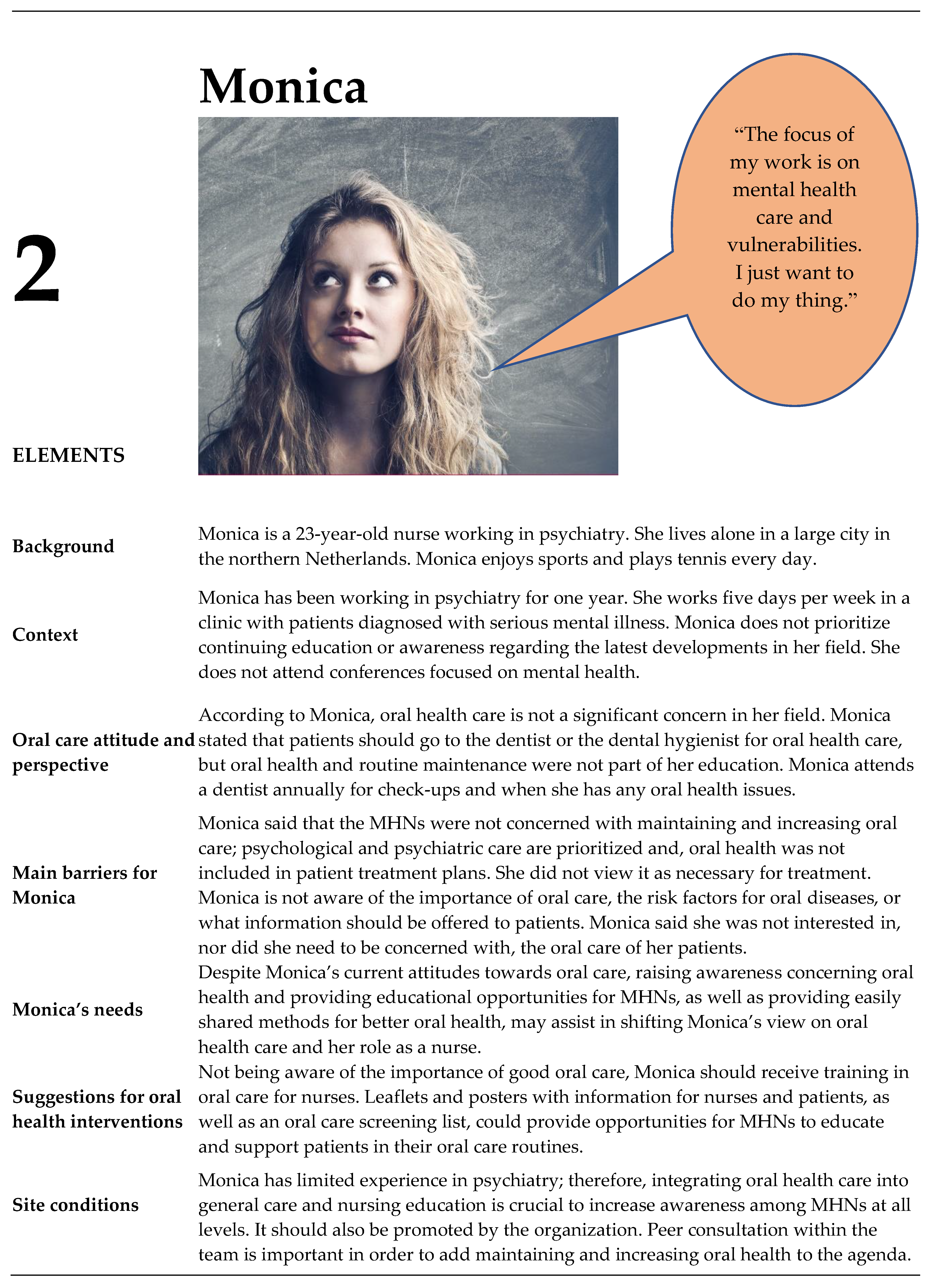

3.2. Personas

3.3. Ecological Validation of the Personas

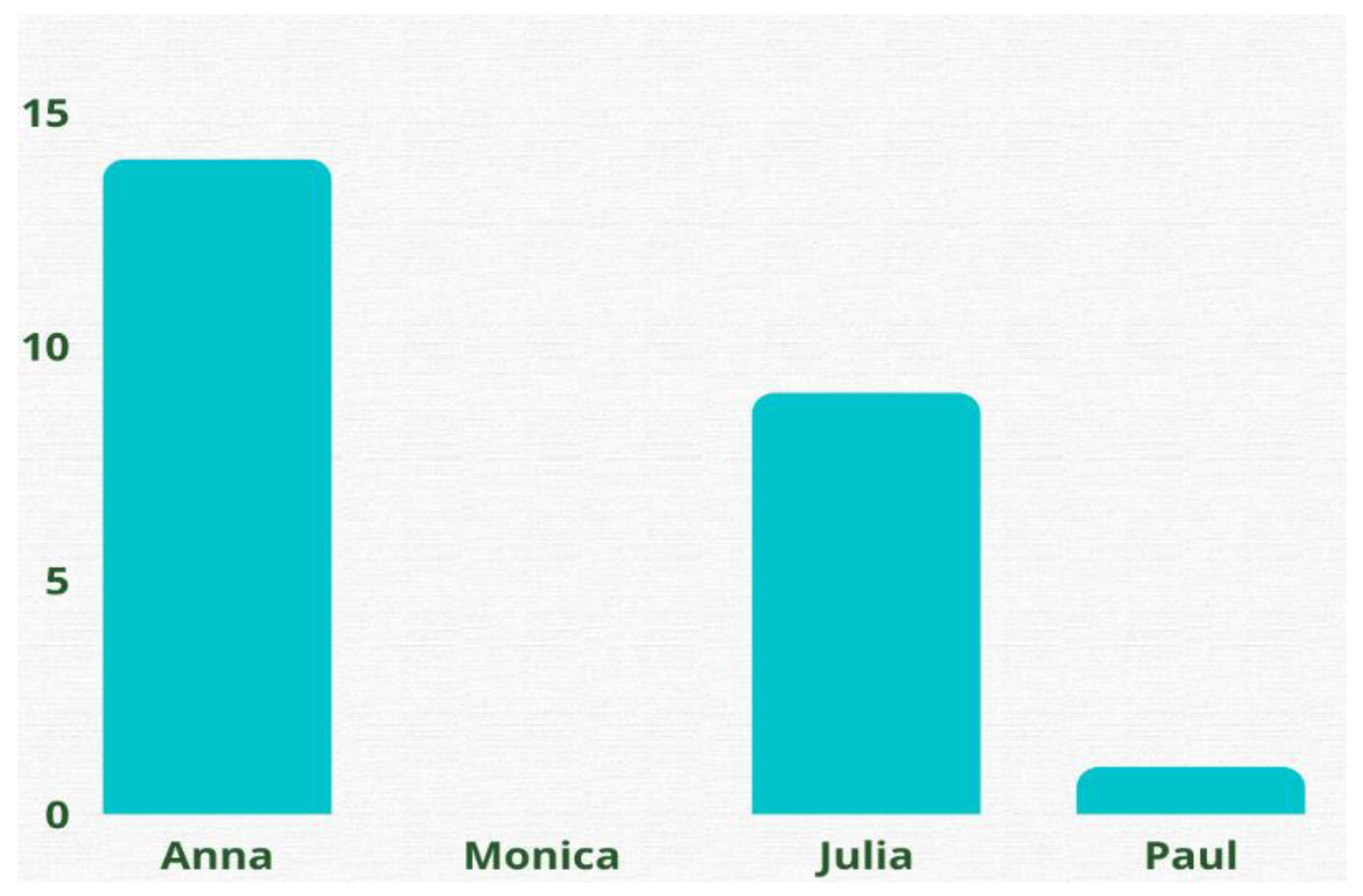

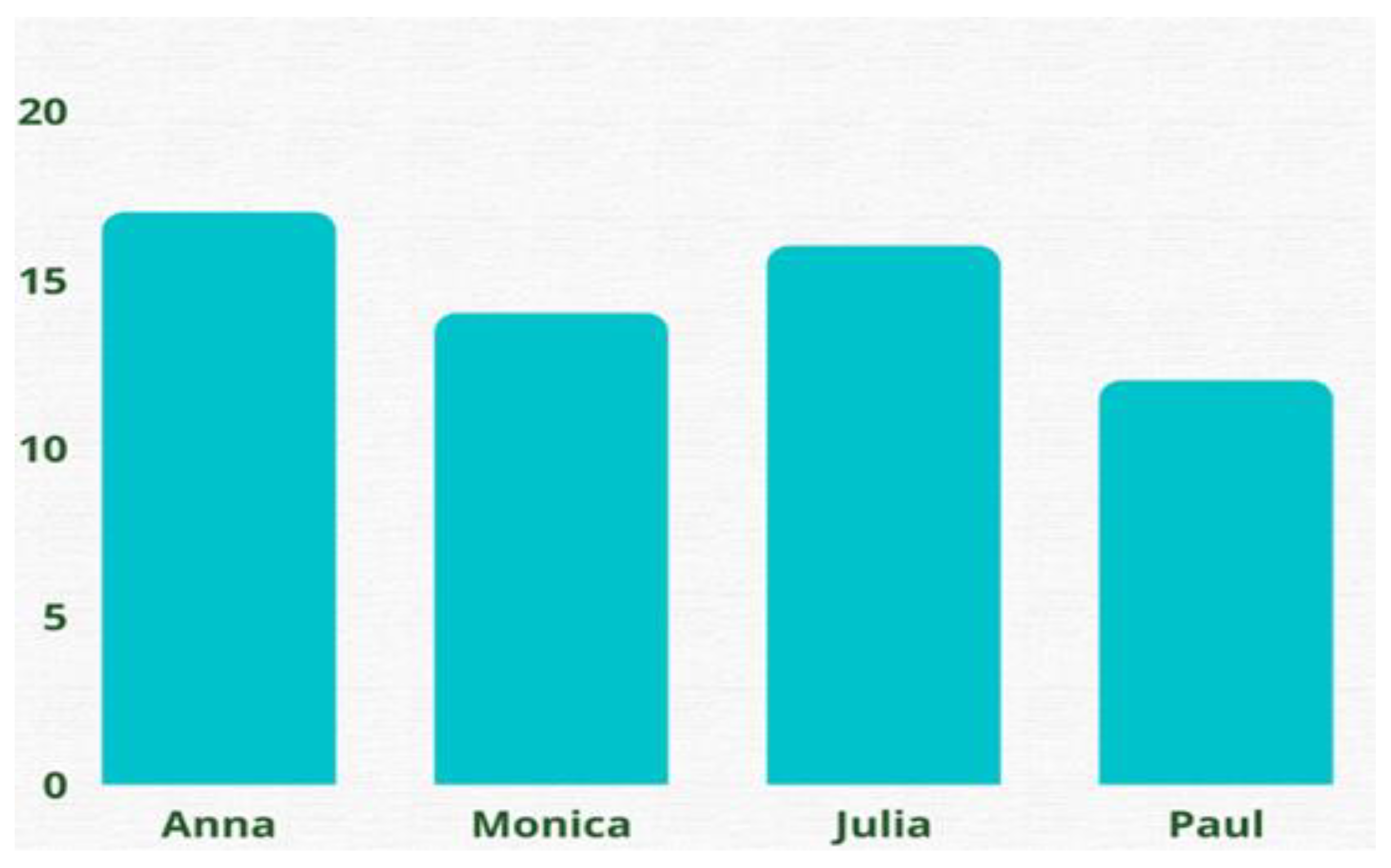

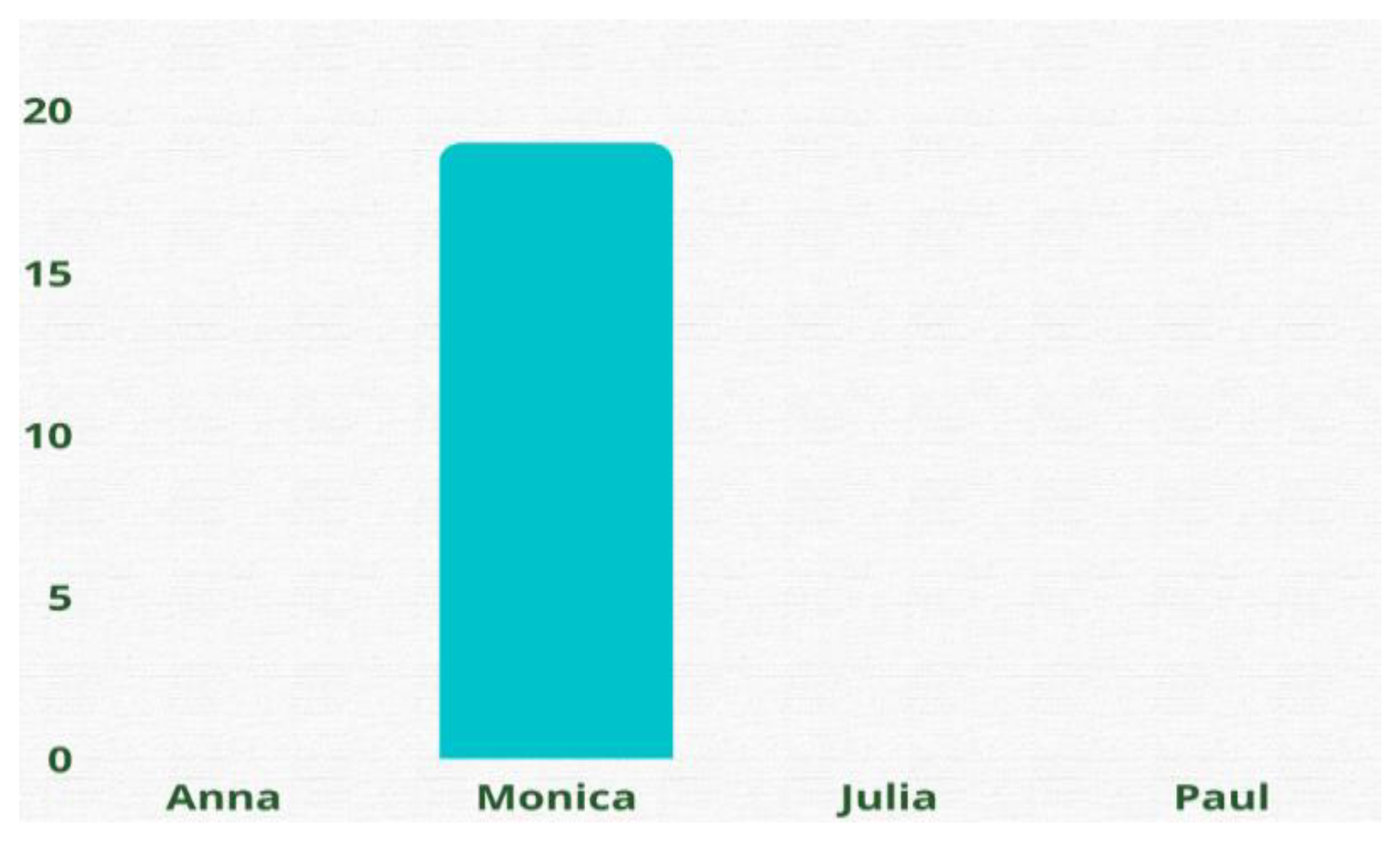

3.3.1. Identification with Personas

But we, as MHNs, do not practice oral health.(Participant 5)

Monica’s perspective is based on the medical model, which focuses on (the absence of) psychiatric complaints. That is not how it works. But also, her limited experience might be an underlaying reason for her current attitude. That means she requires a proper role model.(Participant 7)

3.3.2. Evaluation of Barriers, Needs, Interventions and Site Conditions

This is so recognizable. Not all patients have a toothbrush and toothpaste. I had a patients who had three tubes of toothpaste and no toothbrush, our team found this out three months after the patient’s admission. Nobody does anything about this.(Participant 2)

Today, I had a 28-year-old boy who came to me because he had gum problems. He had not brushed his teeth for a long time. He did not have any materials with him, but we have them. We must show more initiative in an earlier stage because he had already been on admission with us for 9 days.(Participant 18)

Short, 2 min videos would be useful. If I must do something at home (e.g., adjust a derailleur for a bicycle), I quickly look at YouTube, then you can see what needs to be done. And it is relevant to quickly see an example.(Participant 1)

3.3.3. Current Oral Care and the Future of Oral Care in Mental Health Care

4. Discussion

Strength and Limitations of this Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Profession | n | Male/Female | Age in Years | Educational Level | Years of Working Experience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mental health nurse | 1 | Female | 46 | Bachelor of Nursing | 21 |

| 2 | Mental health nurse | 1 | Female | 51 | Bachelor of Nursing | 15 |

| 3 | Mental health nurse | 1 | Female | 25 | Bachelor of nursing | 4 |

| 4 | Mental health nurse | 1 | Male | 53 | Bachelor of Nursing | 7 |

| 5 | Master advanced nurse practitioner | 1 | Female | 31 | Master advanced Nursing Practice | 9 |

| 6 | Master advanced nurse practitioner | 1 | Female | 43 | Master advanced Nursing Practice | 15 |

| 7 | Student Master advanced nurse practitioner | 1 | Female | 27 | Master advanced Nursing Practice | 4 |

| 8 | Mental health nursing student | 1 | Female | 23 | Student Bachelor of Nursing (last year) | 1 |

| 9 | Expert by experience | 1 | Male | 46 | Associate degree for Experts by Experience | 5 |

| 10 | Oral health hygienist | 1 | Female | 37 | Bachelor Oral Health Hygienist | 12 |

Appendix B

| Characteristics|Participant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender M/F | M | F | F | F | F | F | M | M | F |

| Age | 38 | 28 | 30 | 45 | 46 | 38 | 37 | 31 | 31 |

| Education | Nurse sciences and MANP | HBO-V | HBO-V | HBO-V | MANP | MANP | HBO-V, MSc EBP | HBO-V | HBO-V |

| Current job position | |||||||||

| Mental health nurse | x | ||||||||

| Mental health nurse specialist | x | x | x | ||||||

| Mental health nurse specialist i.o. | x (2nd) | x (1st) | x (2nd) | x (1st) | x (3rd) | ||||

| Student nursing | |||||||||

| Current team working | |||||||||

| HIC | x | ||||||||

| VIP | x | ||||||||

| FACT | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Other | Clinical long-term care | IHT | Poli-clinic | ||||||

| Current population working | |||||||||

| FEP | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Several psychotic episodes | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Chronic course afterpsychosis | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Other | Persona-lity disorder | Youth 12–18 years | Illicit drug related psycho-ses | ||||||

| Years of work experience with this population | |||||||||

| 0–4 years | x | x | x | x | |||||

| 5–9 years | x | ||||||||

| 10–14 years | x | ||||||||

| 15–19 years | x | x | |||||||

| 20–24 years | x | ||||||||

| Other | |||||||||

| Characteristics|Participant | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Gender M/F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | M |

| Age | 33 | 46 | 36 | 22 | 48 | 29 | 36 | 54 | 24 |

| Education | MANP | HBO-V | HBO-V | MBO-V | HBO-V | MANP | HBO-V | MANP | HBO-V |

| Current job position | |||||||||

| Mental health nurse | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Mental health nurse specialist | x | x | |||||||

| Mental health nurse specialist i.o. | x (2nd) | x (2nd) | |||||||

| Student nursing | x | ||||||||

| Current team working | |||||||||

| HIC | x | x | |||||||

| VIP | x | x | x | ||||||

| FACT | x | x | x | ||||||

| Other | Autism | Poli-clinic | |||||||

| Current population working | |||||||||

| FEP | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Several psychotic episodes | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Chronic course after psychosis | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Other | |||||||||

| Years of work experience with this population | |||||||||

| 0–4 years | x | x | x | x | |||||

| 5–9 years | x | x | |||||||

| 10–14 years | x | x | |||||||

| 15–19 years | x | ||||||||

| 20–24 years | |||||||||

| Other |

Appendix C. Short List of ‘Guiding’ Questions for Semi-Structured Interviews

- Looking at your role in the context in which you work, in which persona (or elements the persona) do you most identify? (Please circle as appropriate, you may circle more than one)

- Which elements from this persona are most identifiable for you and why? Can you substantiate this with examples per element?

- Looking at the team of nursing colleagues you work in, which persona is most recognizable? (Please circle as appropriate, you may circle more than one).

- Which persona does not fit a mental health nurse at all? (Please circle as appropriate, you may circle more than one).

- Can you also explain why this persona is not representative for a mental health nurse?

- The personas describe the barriers experienced by MHNs. Which barriers do you recognize most and why? Go back to the personas. What would you like to add to (or change) the barriers and why?

- The personas describe what that mental health nurse needs. Which needs do you most identify with? And why? Go back to the personas for this. What would you like to add to (or change) the needs? And why?

- In the personas, several suggestions for interventions are described. Which suggestions for interventions do you most identify? And why? Are these interventions relevant and useful in your work with clients with a psychotic disorder, and why? Go back to the personas for this. What would you like to add to (or adjust) the interventions? Are these interventions relevant and usable in your work with clients with a psychotic disorder and why?

- The personas describe various site conditions. In which site conditions do you recognize yourself the most? And why? To do this, go back to the personas. What would you like to add to (or change) the site conditions? And why?

- What do you currently offer in terms of oral health care within your team? If nothing is available, what would you like to start with?

- What would you personally need in terms of knowledge, skills, or tools to pay more attention to oral health?

- What would you like to see happen so that in a few years, all MHNs will be paying attention to the oral care of their clients?

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

Appendix G

| Questions | Anna | Monica | Julia | Paul | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The personas describe the barriers experienced by MHNs. Which barriers do you recognize most? * | Patients not motivated Patients have no dental aids and insurance No focus on oral health Time constraints | n = 14 n = 11 n = 9 n = 9 | Psychiatric care is prioritized Oral health is not included in patient treatment plans Not aware of the importance of oral care Not knowing what information should be offered to patients | n = 13 n = 14 n = 2 n = 15 | There has not been any coordination regarding oral health (or any physical issues) Feeling uncomfortable discussing oral care | n = 12 n = 9 | Patients often felt unsure Not know how to integrate this into patient care Not know how to advise patients | n = 9 n = 6 n = 9 |

| The personas describe what the mental health nurse needs. Which needs do you most identify with? * | Additional information, such as key factors and highlights on oral health Instructions on motivational interviewing A focused campaign, including literature An oral care screening list Psychoeducation for clients Know how to start the conversation about maintaining and increasing oral health | n = 12 n = 12 n = 14 n = 8 n = 4 | More awareness concerning oral health Educational opportunities for MHNs Easily shared methods for oral health | n = 5 n = 2 n = 3 | How to discuss oral health and oral care with patients How to increase concern and continuity of oral care | n = 5 n = 6 | Training in oral health care, such as the importance of oral health care, risk factors, and screening for oral health | n = 15 |

| With which suggestions for interventions do you most identify? * | Oral health screening should be included in patients’ medical histories and then integrated into the treatment plan. A digital decision tree Leaflets and posters with information | n = 13 n = 2 n = 7 | Training in oral care for nurses Leaflets and posters with information for nurses and patients Oral care screening list | n = 11 n = 13 | More coordination among the nursing team Additional education to promote better oral health and oral hygiene Leaflets and posters with information for nurses and patients An oral care screening list Short 2 min videos regarding oral health | n = 10 n = 5 n = 7 n = 13 n = 2 | A digital screening app focused on oral care including advice on oral care in different situations (e.g., applying a decision tree) | n = 2 |

| In which site conditions do you recognize yourself the most? * | Materials such as tooth-brushes and toothpastes should be available Peer consultation within the team | n = 16 n = 7 | Integrating oral health care into general care nursing education to increase awareness Peer consultation within the team | n = 7 n = 7 n = 3 | Integration of oral healthcare into the MHN’s daily patient care. Peer consultation within the team is important in order to add the topic of oral health to the agenda. | n = 8 n = 5 | Integration of oral care in patient treatment plans and in the organization | n = 17 |

References

- Petersen, P.E. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous Improvement of Oral Health in the 21st Century—The Approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2003, 31, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, P.E. Priorities for Research for Oral Health in the 21st Century—The Approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent. Health 2005, 22, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kisely, S.; Quek, L.H.; Pais, J.; Lalloo, R.; Johnson, N.W.; Lawrence, D. Advanced Dental Disease in People with Severe Mental Illness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Ehrlich, C.; Kendall, E.; Lawrence, D. Using Avoidable Admissions to Measure Quality of Care for Cardiometabolic and Other Physical Comorbidities of Psychiatric Disorders: A Population-Based, Record-Linkage Analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renvert, S.; Noack, M.J.; Lequart, C.; Roldán, S.; Laine, M.L. The Underestimated Problem of Intra-Oral Halitosis in Dental Practice: An Expert Consensus Review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2020, 12, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, C.; Sampogna, G.; Luciano, M.; del Vecchio, V.; Pocai, B.; Borriello, G.; Giallonardo, V.; Savorani, M.; Pinna, F.; Pompili, M.; et al. Improving Physical Health of Patients with Severe Mental Disorders: A Critical Review of Lifestyle Psychosocial Interventions. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2017, 17, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plana-Ripoll, O.; Musliner, K.L.; Dalsgaard, S.; Momen, N.C.; Weye, N.; Christensen, M.K.; Agerbo, E.; Iburg, K.M.; Laursen, T.M.; Mortensen, P.B.; et al. Nature and Prevalence of Combinations of Mental Disorders and Their Association with Excess Mortality in a Population-Based Cohort Study. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormac, I.; Jenkins, P. Understanding the Importance of Oral Health in Psychiatric Patients. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 1999, 5, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Horvitz-Lennon, M.; Post, E.P.; McCarthy, J.F.; Cruz, M.; Welsh, D.; Blow, F.C. Oral Health in Veterans Affairs Patients Diagnosed with Serious Mental Illness. J. Public Health Dent. 2007, 67, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S. No Mental Health without Oral Health. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, S.; Boonstra, N.; Kronenberg, L.; Keuning-Plantinga, A.; Castelein, S. Oral Health Interventions in Patients with a Mental Health Disorder: A Scoping Review with Critical Appraisal of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, P.C.; John, D.A.; Galfalvy, H.; Kunzel, C.; Lewis-Fernández, R. Oral Health–Related Quality of Life among Publicly Insured Mental Health Service Outpatients with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, S.A.; Castelein, S.; Barf, H.; Kronenberg, L.; Boonstra, N. Risk Factors and Oral Health-Control Comparison between Patients Diagnosed with a Psychotic Disorder (First-Episode) and People from the General Population. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, J.; Jones, V.; Leeman, I.; Lewis, D.; Blankenstein, R. Oral Health Care for People with Mental Health Problems; British Society for Disability and Oral Health: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McCreadie, R.G.; Stevens, H.; Henderson, J.; Hall, D.; McCaul, R.; Filik, R.; Young, G.; Sutch, G.; Kanagaratnam, G.; Perrington, S.; et al. The Dental Health of People with Schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 110, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, K.; Axtelius, B.; SÖderfeldt, B.; Östman, M. Monitoring Oral Health and Dental Attendance in an Outpatient Psychiatric Population. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack-Smith, L.; Hearn, L.; Scrine, C.; Durey, A. Barriers and Enablers for Oral Health Care for People Affected by Mental Health Disorders. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Platania-Phung, C.; Scott, D. Physical Health Care for People with Mental Illness: Training Needs for Nurses. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Scott, D.; Platania-Phung, C. Perceptions of Barriers to Physical Health Care for People with Serious Mental Illness: A Review of the International Literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeuwissen, J.; van Gool, R.; Hermens, M.; van Meijel, B. Leefstijlbevordering bij mensen met een ernstige psychische aandoening: Een nieuwe multidisciplinaire richtlijn. Ned. Tijdschr. Evid. Based Pract. 2015, 13, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curedale, R. Design Thinking: Process & Methods, 5th ed.; Design Community College Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-940805-45-0. [Google Scholar]

- Miaskiewicz, T.; Kozar, K.A. Personas and User-Centered Design: How Can Personas Benefit Product Design Processes? Des. Stud. 2011, 32, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenberger, C.; Good, J.; Keay-Bright, W. Designing Technology for Children with Special Needs: Bridging Perspectives through Participatory Design. CoDesign 2011, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeenk, W.; Sturm, J.; Eggen, B. Empathic Handover: How Would You Feel? Handing over Dementia Experiences and Feelings in Empathic Co-Design. CoDesign 2018, 14, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brest, P.; Roumani, N.; Bade, J. Introduction: Two Complementary Approaches to Solving Problems. In Problem Solving, Human-Centered Design, and Strategic Processes; Stanford PACS: Stanford, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, C. Human-Centered Design vs. Design-Thinking: How They’re Different and How to Use Them Together to Create Lasting Change. Available online: https://blog.movingworlds.org/human-centered-design-vs-design-thinking-how-theyre-different-and-how-to-use-them-together-to-create-lasting-change/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Pruitt, J.; Grudin, J. Personas: Practice and Theory. In Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Designing for User Experiences, San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–7 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Design Council. Eleven Lessons: Managing Design in Eleven Global Companies; Design Council: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, A.; Valentim, N.; Moraes, B.; Zilse, R.; Conte, T. Applying User-Centered Techniques to Analyze and Design a Mobile Application. J. Softw. Eng. Res. Dev. 2018, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, L.; Jonker, T.; Wadman, H.; Wunderink, C.; van Weeghel, J.; Pijnenborg, G.H.M.; van Setten, E.R.H. Targeting Personal Recovery of People with Complex Mental Health Needs: The Development of a Psychosocial Intervention through User-Centered Design. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 635514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Termglinchan, V.; Daswani, S.; Duangtaweesub, P.; Assavapokee, T.; Milstein, A.; Schulman, K. Identifying Solutions to Meet Unmet Needs of Family Caregivers Using Human-Centered Design. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton, S.J. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Purcell, R.; Hickie, I.B.; Yung, A.R.; Pantelis, C.; Jackson, H.J. Clinical Staging: A Heuristic Model for Psychiatry and Youth Mental Health. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, S40–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van’t Veer, J.; Wouters, E.; Veeger, M.; van der Lugt, R. Ontwerpen Voor Zorg en Welzijn; Eerste Druk, Tweede Oplage; Uitgeverij Coutinho: Bussum, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 978-90-469-0691-0. [Google Scholar]

- Coble, J.M.; Maffitt, J.S.; Orland, M.J.; Kahn, M.G. Contextual Inquiry: Discovering Physicians’ True Needs. In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer Application in Medical Care; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1995; pp. 469–473. [Google Scholar]

- Hartson, R.; Pyla, P.S. The UX Book Agile UX Design for a Quality User Experience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 978-0-12-805342-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic Methodological Review: Developing a Framework for a Qualitative Semi-Structured Interview Guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudin, J.; Pruitt, J. Personas, Participatory Design and Product Development: An Infrastructure for Engagement. Proc. PDC 2002, 2, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, C.N.; Milham, R.P. The Personas’ New Clothes: Methodological and Practical Arguments against a Popular Method. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006; Volume 50, pp. 634–636. [Google Scholar]

- Stickdorn, M.; Hormess, M.E.; Lawrence, A.; Schneider, J. (Eds.) This Is Service Design Doing: Applying Service Design Thinking in the Real World; a Practitioners’ Handbook, 1st ed.; O’Reilly: Sebastapol, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4919-2718-2. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Howard, L.; Gamble, C. Supporting Mental Health Nurses to Address the Physical Health Needs of People with Serious Mental Illness in Acute Inpatient Care Settings. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roebroek, L.O.; Bruins, J.; Boonstra, A.; Veling, W.; Jörg, F.; Sportel, B.E.; Delespaul, P.A.; Castelein, S. The Effects of a Computerized Clinical Decision Aid on Clinical Decision-Making in Psychosis Care. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 156, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.; Happell, B.; Browne, G. Talking or Avoiding? Mental Health Nurses’ Views about Discussing Sexual Health with Consumers. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 20, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, W.R. The Global Presence of Holistic Nursing. J. Holist. Nurs. 2011, 29, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, S.; Castelein, S.; Malda, A.; Kronenberg, L.; Boonstra, N. Oral Health Experiences and Needs among Young Adults after a First-Episode Psychosis: A Phenomenological Study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 25, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, A.L.; Purwaningtyas, R.A.; Astuti, D. The Effectiveness of Traditional Media (Leaflet and Poster) to Promote Health in a Community Setting in the Digital Era: A Systematic Review. J. Ners 2019, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Kamp, A.; Fersch, B. Detached Co-Involvement in Interactional Care: Transcending Temporality and Spatiality through MHealth in a Social Psychiatry out-Patient Setting. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Merinder, L.B.; Belgamwar, M.R. Psychoeducation for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaars, B.; Weening-Verbree, L.F.; Jerković-Ćosić, K.; Schoonmade, L.; Bleijenberg, N.; de Wit, N.J.; van der Heijden, G.J.M.G. Measurement Properties of Oral Health Assessments for Non-Dental Healthcare Professionals in Older People: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harderwijk, H. Translating and Validating the Dutch Version of the Oral Health Assessment Tool for Older; University of Utrecht: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, J.M.; King, P.L.; Spencer, A.J.; Wright, F.A.C.; Carter, K.D. The Oral Health Assessment Tool—Validity and Reliability. Aust. Dent. J. 2005, 50, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chivilgina, O.; Wangmo, T.; Elger, B.S.; Heinrich, T.; Jotterand, F. mHealth for Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Management: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 642–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almomani, F.; Williams, K.; Catley, D.; Brown, C. Effects of an Oral Health Promotion Program in People with Mental Illness. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.M.; Scott, E.S. A New Leadership Development Model for Nursing Education. J. Prof. Nurs. 2019, 35, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massanari, A.L. Designing for Imaginary Friends: Information Architecture, Personas and the Politics of User-Centered Design. New Media Soc. 2010, 12, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, J.O.; Jung, S.; Jansen, B.J. Are Data-Driven Personas Considered Harmful?: Diversifying User Understandings with More than Algorithms. Pers. Stud. 2021, 7, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuipers, S.; Castelein, S.; Kronenberg, L.; Veer, J.v.’t.; Boonstra, N. A Human-Centered Design Approach to Develop Oral Health Nursing Interventions in Patients with a Psychotic Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043475

Kuipers S, Castelein S, Kronenberg L, Veer Jv’t, Boonstra N. A Human-Centered Design Approach to Develop Oral Health Nursing Interventions in Patients with a Psychotic Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043475

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuipers, Sonja, Stynke Castelein, Linda Kronenberg, Job van ’t Veer, and Nynke Boonstra. 2023. "A Human-Centered Design Approach to Develop Oral Health Nursing Interventions in Patients with a Psychotic Disorder" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043475

APA StyleKuipers, S., Castelein, S., Kronenberg, L., Veer, J. v. ’t., & Boonstra, N. (2023). A Human-Centered Design Approach to Develop Oral Health Nursing Interventions in Patients with a Psychotic Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043475