Physical Activity Patterns According to the Type of Physical Education Classes by Sex and Obesity among Korean Adolescents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Statistical Analyses

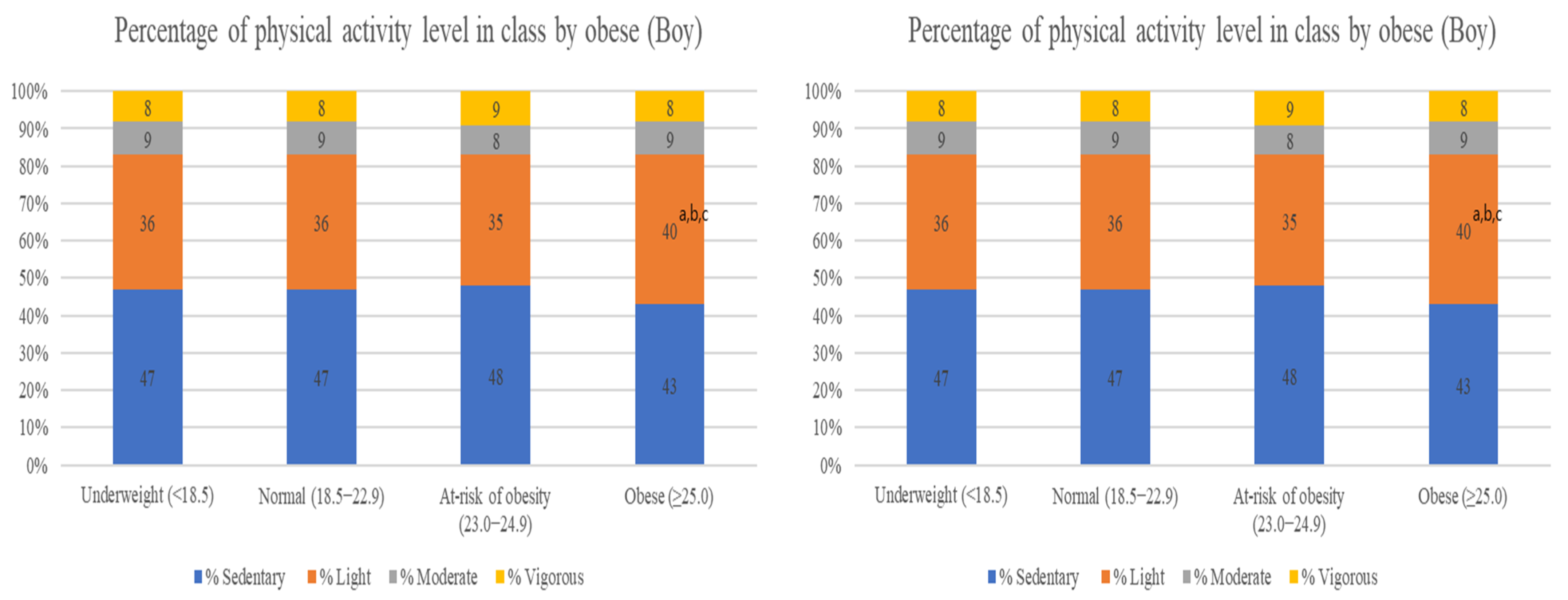

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2016: Monitoring Health for the SDGs Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9241565268. [Google Scholar]

- Abarca-Gómez, L.; Abdeen, Z.A.; Hamid, Z.A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; Acosta-Cazares, B.; Acuin, C.; Adams, R.J.; Aekplakorn, W.; Afsana, K.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128 · 9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, S.A.; Hardy, S.T.; Jones, R.; Ng, C.; Kramer, M.R.; Narayan, K.M.V. Changes in the Incidence of Childhood Obesity. Pediatrics 2022, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, A.P.; Dengel, D.R.; Lubans, D.R. Supporting Public Health Priorities: Recommendations for Physical Education and Physical Activity Promotion in Schools. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 57, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairclough, S.; Stratton, G. Physical activity levels in middle and high school physical education: A review. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2005, 17, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.; Rosenkranz, R.R.; Peralta, L.R.; Bennie, A.; Fahey, P.; Lubans, D.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to increase moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in school physical education lessons. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, K.; Donovan, C.; Gibbone, A. Investigating the Effects of Federal Funding on Students’ Attitudes Toward Physical Education. Phys. Educ. 2020, 77, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S. Attitude research in physical education: A review. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, É.R.; Ihle, A.; Gouveia, B.R.; Rodrigues, A.J.; Marques, A.; Freitas, D.L.; Kliegel, M.; Correia, A.L.; Alves, R.; Lopes, H. Students’ attitude toward physical education: Relations with physical activity, physical fitness, and self-concept. Phys. Educ. 2019, 76, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.J.; Sirard, J.R.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Adolescents’ attitudes toward sports, exercise, and fitness predict physical activity 5 and 10 years later. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, K.; Mercier, K.; Centeio, E.; Barcelona, J.; Phillips, S.; Garn, A.C. Development of Youth Physical Activity Attitude Scale (YPAAS) for elementary and middle school students. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2021, 25, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegele, J.A.; Hodge, S.R. Quantitative methodology: A guide for emerging physical education and adapted physical education researchers. Phys. Educ. 2015, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Hall, K. Physical education or playtime: Which is more effective at promoting physical activity in primary school children? BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evenson, K.R.; Catellier, D.J.; Gill, K.; Ondrak, K.S.; McMurray, R.G. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J. Sport. Sci. 2008, 26, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Loprinzi, P.D.; Moore, R.; Pfeiffer, K.A. Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.; Loprinzi, P.; Kim, H.; Kang, M. Temporal Trends in the Association between Participation in Physical Education and Physical Activity among U.S. High School Students, 2011–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, R.; Salmon, J.; Islam, S.M.S.; Khan, A. Physical education class participation is associated with physical activity among adolescents in 65 countries. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.S.; Chaput, J.P.; Tremblay, M.S. Participation frequency in physical education classes and physical activity and sitting time in Brazilian adolescents. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Oh, H.; Sheng, H. Middle school students’ body mass index and physical activity levels in physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, R.K.; Motl, R.W.; Saunders, R.; Felton, G.; Ward, D.S.; Dowda, M.; Pate, R.R. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school-based physical-activity intervention among adolescent girls. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, R.K.; Motl, R.W.; Saunders, R.; Felton, G.; Ward, D.S.; Dowda, M.; Pate, R.R. Enjoyment mediates effects of a school-based physical-activity intervention. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, S.; Stratton, G. ‘Physical education makes you fit and healthy’. Physical education’s contribution to young people’s physical activity levels. Health Educ. Res. 2005, 20, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, M.; Warburton, P.; Coy, M. Observation of children’s physical activity levels in primary school: Is the school an ideal setting for meeting government activity targets? Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2007, 13, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towne, S.D., Jr.; Ory, M.G.; Smith, M.L.; Peres, S.C.; Pickens, A.W.; Mehta, R.K.; Benden, M. Accessing physical activity among young adults attending a university: The role of sex, race/ethnicity, technology use, and sleep. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairclough, S.; Hilland, T.; Stratton, G.; Ridgers, N. ‘Am I able? Is it worth it?’Adolescent girls’ motivational predispositions to school physical education: Associations with health-enhancing physical activity. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2012, 18, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Motl, R.W.; Dishman, R.K.; Saunders, R.; Dowda, M.; Felton, G.; Pate, R.R. Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in adolescent girls. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 21, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Prochaska, J.J.; Taylor, W.C. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2000, 32, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, S.; Subramaniam, P.R. Student attitude toward physical education and physical activity: A review of measurement issues and outcomes. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1999, 19, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, H.S.; Şahin, F.N.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P.; Bianco, A. School-based intervention programs for preventing obesity and promoting physical activity and fitness: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Slymen, D.J.; McKenzie, T.L. A longitudinal study of children’s enjoyment of physical education. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2003, 15, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Fairclough, S. Assessing free-living physical activity using accelerometry: Practical issues for researchers and practitioners. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2011, 11, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (N = 2633) | Boys (n = 1305) | Girls (n = 1328) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 13.77 ± 0.65 | 13.82 ± 0.65 | 13.73 ± 0.62 | 0.002 ** |

| Height (cm) | 162.36 ± 7.35 | 166.40 ± 6.91 | 158.38 ± 5.31 | <0.001 *** |

| Weight (kg) | 61.92 ± 13.99 | 61.92 ± 13.99 | 53.02 ± 10.10 | <0.001 *** |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.68 ± 4.06 | 22.27 ± 4.42 | 21.09 ± 3.58 | <0.001 *** |

| Group (n, %) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 572 (21.72) | 264 (20.23) | 308 (23.19) | <0.001 *** |

| Normal (18.5–22.9 kg/m2) | 1300 (49.37) | 560 (42.91) | 740 (55.72) | |

| At-risk for obesity (23.0–24.9 kg/m2) | 270 (10.25) | 155 (11.88) | 115 (8.66) | |

| Obese (≥25.0 kg/m2) | 491 (18.65) | 326 (24.98) | 165 (12.42) |

| Sedentary | Light | Moderate | Vigorous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 21.30 ± 7.68 | 16.11 ± 5.19 | 4.07 ± 2.45 | 3.48 ± 2.89 |

| Normal (18.5–22.9) | 21.13 ± 7.55 | 16.12 ± 5.27 | 4.05 ± 2.22 | 3.67 ± 3.18 |

| At-risk for obesity (23.0–24.9) | 21.80 ± 8.74 | 15.50 ± 5.88 b | 3.69 ± 2.05 | 3.95 ± 3.71 |

| Obese (≥25.0) | 19.46 ± 7.71 | 17.87 ± 5.48 abc | 4.14 ± 2.23 | 3.38 ± 2.57 |

| p-value | 0.037 * | <0.001 *** | 0.380 | 0.379 |

| Girl | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 14.72 ± 7.89 | 17.22 ± 4.54 | 6.23 ± 3.02 | 6.80 ± 4.65 |

| Normal (18.5–22.9) | 15.13 ± 7.56 | 17.39 ± 4.74 | 6.11 ± 2.89 | 6.31 ± 4.15 |

| At-risk for obesity (23.0–24.9) | 13.22 ± 7.03 b | 17.71 ± 4.87 | 6.59 ± 3.22 | 7.40 ± 4.83 b |

| Obese (≥25.0) | 13.58 ± 7.38 b | 19.00 ± 5.15 ab | 6.32 ± 3.00 | 6.03 ± 3.91 c |

| p-value | 0.004 ** | <0.001 *** | 0.341 | 0.004 ** |

| Sedentary | Light | Moderate | Vigorous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | −0.039 (−0.129–0.050) | 0.038 (−0.022–0.098) | 0.015 (−0.014–0.043) | −0.019 (−0.051–0.014) |

| Normal (18.5−22.9) | −0.046 (−0.101–0.008) | 0.041 * (0.003–0.078) | 0.009 (−0.008–0.026) | −0.010 (−0.028–−0.009) |

| At-risk for obesity (23.0−24.9) | 0.005 (−0.170–0.180) | 0.019 (−0.097–0.135) | −0.006 (−0.046–0.034) | −0.024 (−0.093–0.045) |

| Obese (≥25.0) | −0.066 (−0.193–0.061) | 0.071 (−0.026–0.169) | −0.012 (−0.050–0.026) | −0.012 (−0.056–0.032) |

| Girl | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | −0.135 * (−0.227–−0.442) | 0.007 (−0.048–0.063) | 0.059 * (0.020–0.099) | 0.064 * (0.002–0.128) |

| Normal (18.5−22.9) | −0.142 * (−0.199–−0.084) | 0.009 (−0.027–0.046) | 0.065 * (0.042–0.087) | 0.061 * (0.028–0.094) |

| At−risk for obesity (23.0−24.9) | −0.137 * (−0.231–−0.043) | −0.022 (−0.096–0.052) | 0.085 * (0.036–0.134) | 0.068 * (0.001–0.135) |

| Obese (≥25.0) | −0.143 * (−0.228–−0.058) | 0.032 (−0.032–0.095) | 0.074 * (0.041–0.106) | 0.030 (−0.015–0.075) |

| Sedentary | Light | Moderate | Vigorous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.075 (−0.044–0.195) | −0.053 (−0.133–0.027) | −0.030 (−0.067–−0.008) | −0.011 (−0.033–0.054) |

| Normal (18.5−22.9) | 0.181 * (0.091–0.270) | −0.113 * (−0.175–−0.050) | −0.042 * (−0.070–−0.014) | −0.024 (−0.055–−0.008) |

| At-risk for obesity (23.0−24.9) | 0.270 * (0.040–0.500) | −0.216 * (−0.366–−0.066) | −0.051 (−0.104–−0.002) | −0.001 (−0.093–0.095) |

| Obese (≥25.0) | 0.056 * (−0.145–0.256) | −0.064 (−0.219–0.091) | −0.029 (−0.089–0.030) | 0.045 (−0.023–0.114) |

| Girls | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | −0.048 (−0.208–0.112) | −0.085 (−0.180–0.009) | 0.039 (−0.030–0.108) | −0.097 (−0.012–0.205) |

| Normal (18.5−22.9) | 0.002 (−0.092–0.095) | −0.056 (−0.115–0.003) | 0.020 (−0.017–0.058) | −0.039 (−0.014–0.092) |

| At−risk for obesity (23.0−24.9) | −0.180 * (−0.350–−0.010) | 0.088 (−0.044–0.218) | 0.065 (−0.026–0.156) | 0.035 (−0.087–0.156) |

| Obese (≥25.0) | −0.024 (−0.141–0.093) | −0.034 (−0.120–0.052) | −0.018 (−0.028–0.064) | −0.043 (−0.018–0.104) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, G.; Jang, S.; Kong, S. Physical Activity Patterns According to the Type of Physical Education Classes by Sex and Obesity among Korean Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043151

Lee G, Jang S, Kong S. Physical Activity Patterns According to the Type of Physical Education Classes by Sex and Obesity among Korean Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043151

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Gyuil, Seyong Jang, and Sunga Kong. 2023. "Physical Activity Patterns According to the Type of Physical Education Classes by Sex and Obesity among Korean Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043151

APA StyleLee, G., Jang, S., & Kong, S. (2023). Physical Activity Patterns According to the Type of Physical Education Classes by Sex and Obesity among Korean Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043151