A Study of Psychometric Instruments and Constructs of Work-Related Stress among Seafarers: A Qualitative Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

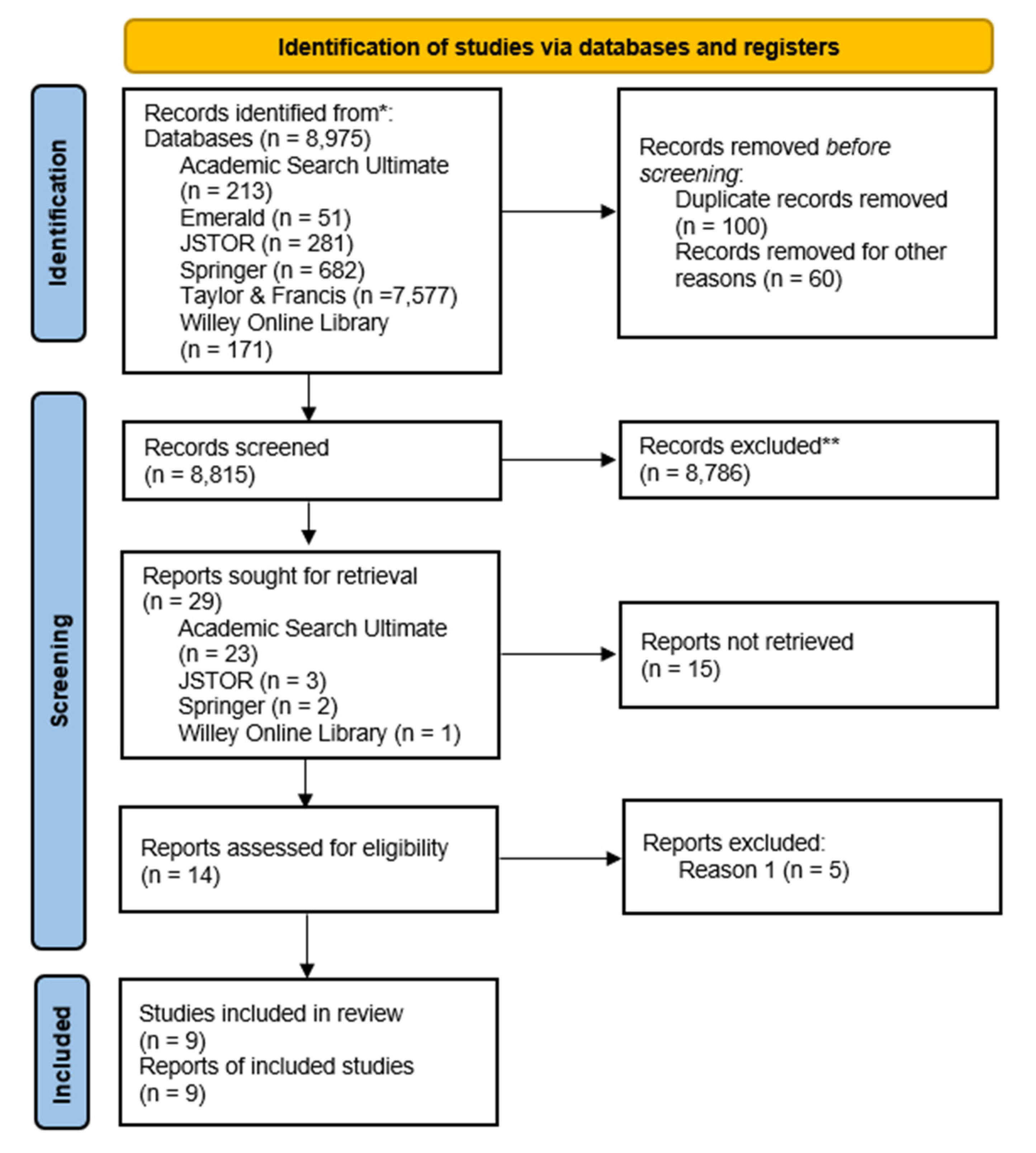

2.1. Phase 1: A Systematic Review

2.1.1. Database Search

2.1.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.1.3. Quality Assessment and Result Synthesis

2.2. Phase 2: A Qualitative Study Using Semi-Structured Interview

3. Results

3.1. Valid and Reliable Instruments in Measuring Work-Related Stress among Seafarers

3.2. Work-Related Stress Constructs among Malaysian Seafarers

3.2.1. Physical Stress

3.2.2. Personal Issues

3.2.3. Social Living on Board

3.2.4. Technostress

3.2.5. Work Factors

3.2.6. COVID-19 Pandemic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iversen, R.T. The Mental Health of Seafarers. Int. Marit. Health 2012, 63, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Håvold, J.I. Stress on the Bridge of Offshore Vessels: Examples from the North Sea. Saf. Sci. 2015, 71, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J.; MacLachlan, M.; Stilz, R.; Cox, H.; Doyle, N.; Fraser, A.; Dyer, M. Positive Psychology and Well-Being at Sea. In Maritime Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Carotenuto, A.; Molino, I.; Fasanaro, A.M.; Amenta, F. Psychological Stress in Seafarers: A Review. Int. Marit. Health 2012, 63, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- af Geijerstam, K.; Svensson, H. Ship Collision Risk—An Identification and Evaluation of Important Factors in Collisions with Offshore Installations. 2008, p. 137. Available online: http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/1689121 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Wanyoike, B.W. Depression Causes Suicide. J. Lang. Technol. Entrep. Africa 2014, 5, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh, J.; MacLachlan, M.; Coyle, C.; Kavanagh, B. Perceptions of Well-Being, Resilience and Stress amongst a Sample of Merchant Seafarers and Superintendents. Marit. Stud. 2019, 18, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.S.; Lee, P.T.W.; Lee, J.K. Burnout in Seafarers: Its Antecedents and Effects on Incidents at Sea. Marit. Policy Manag. 2017, 44, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Huang, B.; Shen, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y. Association between Social Support and Health-Related Quality of Life among Chinese Seafarers: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, N.; Johar, S.S.H.; Ismail, F.B. The Effect of Employee Happiness on Employee Performance in UAE: The Moderating Role of Spirituality and Emotional Wellness. J. Adm. Bus. Stud. 2019, 5, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurcholis, G.; Qurniawati, M. Psychological Well Being, Stress at Work and Safety Behaviour at Sea of Seafarer on Shipping Company. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 12, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, M.; Jensen, H.J. Stress and Strain among Seafarers Related to the Occupational Groups. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.U.; Aston, J. A Relationship between Occupational Stress and Organisational Commitment of It Sector’s Employees in Contrasting Economies. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 14, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, M.; Jensen, H.J. Stress and Strain among Merchant Seafarers Differs across the Three Voyage Episodes of Port Stay, River Passage and Sea Passage. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slišković, A. Occupational Stress in Seafaring. In Maritime Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Carotenuto, A.; Fasanaro, A.M.; Molino, I.; Sibilio, F.; Saturnino, A.; Traini, E.; Amenta, F. The Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) for Assessing Stress of Seafarers on Board Merchant Ships. Int. Marit. Health 2013, 64, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengamani, J.; Murugan, M.S. A Study on the Factors Influencing the Seafarers’ Stress. AMET Int. J. Manag. 2012, 4, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, M.; Jensen, H.J.; Latza, U.; Baur, X. Seafaring Stressors Aboard Merchant and Passenger Ships. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeżewska, M.; Leszczyńska, I.; Jaremin, B. Work Related Stress in Seamen. Int. Marit. Health 2006, 57, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, M.; Jensen, H.J.; Wegner, R. Burnout Syndrome in Seafarers in the Merchant Marine Service. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2013, 86, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, M.; Hogan, B.; Jensen, H.J. Systematic Review of Maritime Field Studies about Stress and Strain in Seafaring. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2013, 86, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comperatore, C.A.; Rivera, P.K.; Kingsley, L. Enduring the Shipboard Stressor Complex: A Systems Approach. Aviat. Sp. Environ. Med. 2005, 76, B108–B118. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, A.U.; Oino, I. Managerial Challenges for Software Houses Related to Work, Worker and Workplace: Stress Reduction and Sustenance of Human Capital. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J.; MacLachlan, M.; Kavanagh, B. The Positive Psychology of Maritime Health. J. Inst. Remote Health Care 2016, 7, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rengamani, J.; Venkatraman, V. Study on the Job Satisfaction of Seafarers While on Stress Predicament. Int. J. Mark. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 6, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, R.Z.A.R.; Zalam, W.Z.M.; Foster, B.; Afrizal, T.; Johansyah, M.D.; Saputra, J.; Ali, S.N.M. Psychosocial Work Environment and Teachers’ Psychological Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Job Control and Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, N.; MacLachlan, M.; Fraser, A.; Stilz, R.; Lismont, K.; Cox, H.; McVeigh, J. Resilience and Well-Being amongst Seafarers: Cross-Sectional Study of Crew across 51 Ships. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briner, R.B.; Reynolds, S. The Costs, Benefits, and Limitations of Organizational Level Stress Interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.G.; Farah, A.; Apkinar-Sposito, C. Measuring the Immeasurable! An Overview of Stress & Strain Measuring Instruments. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 480. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, J.; Phillips, C. The Use of Flipped Classrooms in Higher Education: A Scoping Review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 25, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviews of Observational Epidemiological Studies Reporting Prevalence and Cumulative Incidence Data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Mu, P. Conducting Systematic Reviews of Association (Etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute’s Approach. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative Research Synthesis: Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviewers Utilizing Meta-Aggregation. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, R. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Do Qualitative Interviews in Building Energy Consumption Research Produce Reliable Knowledge? J. Build. Eng. 2015, 1, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.G.; Fischhoff, B.; Bostrom, A.; Atman, C.J. Risk Communication: A Mental Models Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 0521802237. [Google Scholar]

- Rydstedt, L.W.; Lundh, M. An Ocean of Stress? The Relationship between Psychosocial Workload and Mental Strain among Engine Officers in the Swedish Merchant Fleet. Int. Marit. Health 2010, 62, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, E.; Compare, A. Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWB). In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 5152–5156. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G. Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology; Spacapan, S., Oskamp, S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.; Brisson, C.; Kawakami, N.; Houtman, I.; Bongers, P.; Amick, B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An Instrument for Internationally Comparative Assessments of Psychosocial Job Characteristics. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, K.O.B.; de Araújo, T.M.; Carvalho, F.M.; Karasek, R. The Job Content Questionnaire in Various Occupational Contexts: Applying a Latent Class Model. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, C. Impact of Work–Family Conflict, Job Stress and Job Satisfaction on Seafarer Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, A.L. Health and Stress of Seafarers. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1985, 11, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, L.J.; Al-sahrawardee, H.M.S.M.; Karoom, C.; Muqdad, B. The Role of Stress Testing Scenarios in Reducing the Banks-Risks: An Applied Study. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 20, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, K.A.; Charles, S.T.; Turiano, N.A.; Almeida, D.M. Personality and Stressor-Related Affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Wardsworth, E.; Smith, A. Seafarers’ Fatigue: A Review of the Recent Literature. Int. Marit. Health 2008, 59, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Papachristou, A.; Stantchev, D.; Theotokas, I. The Role of Communication to the Retention of Seafarers in the Profession. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2015, 14, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J.; MacLachlan, M.; Vallières, F.; Hyland, P.; Stilz, R.; Cox, H.; Fraser, A. Identifying Predictors of Stress and Job Satisfaction in a Sample of Merchant Seafarers Using Structural Equation Modeling. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brivio, E.; Gaudioso, F.; Vergine, I.; Mirizzi, C.R.; Reina, C.; Stellari, A.; Galimberti, C. Preventing Technostress through Positive Technology. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellberg, C.; Susi, T. Technostress in the Office: A Distributed Cognition Perspective on Human–Technology Interaction. Cogn. Technol. Work 2014, 16, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slišković, A. Seafarers’ Well-Being in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Work 2020, 67, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauksztat, B.; Grech, M.; Kitada, M.; Jensen, R.B. Seafarers’ Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Report; World Maritime University: Malmö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, K.F.; Loh, H.S.; Zhou, Q.; Wong, Y.D. Determinants of Job Satisfaction and Performance of Seafarers. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 110, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.Z.A.R.; Saputra, J.; Akmal, N.A. The Effects of Work-Family Conflict on Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: A Study in the East Coast of Malaysia. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 13, 542–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, R.; Saputra, J.; Bakar, A.A.; Dagang, M.M.; Nazilah, S.; Ali, M.; Yasin, M. Role of Supply Chain Management on the Job Control and Social Support for Relationship between Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag 2019, 8, 907–913. [Google Scholar]

| Source(s) | Identification(s) |

|---|---|

| Academic Search Ultimate | (TITLE((“Work-stress AND Seafarers” OR “Job Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Occupational Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Seafarers”)) AND TITLE ((“Work-stress OR occupational stress OR job stress AND seafarers”)) |

| Emerald Journal | (TITLE((“Work-stress AND Seafarers” OR “Job Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Occupational Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Seafarers”)) AND TITLE ((“Work-stress OR occupational stress OR job stress AND seafarers”)) |

| JSTOR | (TITLE((“Work-stress AND Seafarers” OR “Job Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Occupational Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Seafarers”)) AND TITLE ((“Work-stress OR occupational stress OR job stress AND seafarers”)) |

| Springer Link | (TITLE((“Work-stress AND Seafarers” OR “Job Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Occupational Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Seafarers”)) AND TITLE ((“Work-stress OR occupational stress OR job stress AND seafarers”)) |

| Taylor & Francis Online | (TITLE((“Work-stress AND Seafarers” OR “Job Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Occupational Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Seafarers”)) AND TITLE ((“Work-stress OR occupational stress OR job stress AND seafarers”)) |

| Wiley Online Library | (TITLE((“Work-stress AND Seafarers” OR “Job Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Occupational Stress AND Seafarers” OR “Seafarers”)) AND TITLE ((“Work-stress OR occupational stress OR job stress AND seafarers”)) |

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Period | 1988–2020 | Outside of those years |

| Language | English | Non-English |

| Article type | Original (qualitative and quantitative) | Other than the original (any review, letter and editorial, or thesis) |

| Study focus | Work-related stress; Seafarers | Other than inclusion criteria |

| Perspective | Psychological health | Medical and experimental health |

| Author(s) (Year); Article Title | Study Design | Study Population and Sample | Dimensions | Measurement Instruments; Cronbach Alpha | Theoretical Basis (Measure) | Data Collection Method | Related Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McVeigh, J., MacLachlan, M., Coyle, C., & Kavanagh (2019) [7] Identifying predictors of stress and job satisfaction in a sample of merchant seafarers using structural equation modelling | Quantitative and cross-sectional design (two phases of study) | Merchant seafarers (n = 575). They are officers and ratings/crew working in the organization’s fleet on liquefied natural gas carriers, product oil tankers, and crude oil tankers, on a global basis. | No dimensions | Perceived stress scale version 4 (PSS4) The value is 0.55 and considered accepted as the same value has been found by the test developer, Cohen et al. (1985) [40] | Lazarus original transactional model | A secondary data analysis, using questionnaires administered at two time points to seafarers within a large shipping organization | Dispositional resilience and instrumental work are the important contributors to psychosocial well-being in this sample of merchant seafarers |

| Doyle, MacLachlan, Fraser, Stilz, Lismont, Cox & McVeigh (2016) [27] Resilience and well-being among seafarers: cross-sectional studyof crew across 51 ships | Quantitative and cross-sectional design | Seafarers from an international shipping company (n= 387) ratings, crew, officers, engineers, and catering staff that had been on board their ship between 0 and 24 weeks. | No dimensions | Perceived Stress scale version 4 (PSS4) The value is 0.57, comparable to estimates in the literature (Cohen and Williamson 1988) [41] | Lazarus original transactional model | Data from questionnaires were emailed to 53 tanker vessels in an international shipping company | Duration at sea was not related to stress among seafarers and the result found high level of resilience, longer seafaring experience and greater instrumental work support was significantly associated with lower levels of stress. |

| Carotenuto, Fasanaro, Molino, Sibilio, Saturnino, Traini & Amenta, (2013) [16] The Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) for assessing the stress of seafarers on board merchant ships | Quantitative and cross-sectional design | Male seafarers (n = 162) which consist of (1 Argentine, 1 Bulgarian, 122 Indians, 37 Italians and 1 Romanian) on board of 7 tankers in a shipping company | Anxiety, depressed mood, positive well-being, self-control, general health, and vitality | The general value is 0.80 and the highest 0.92 (Grossi & compare, 2014) [39] | No theoretical basis | Questionnaire was sent on board together with instructions and extensive explanations on how to administer it between August 2012 and April 2013. Captains of the ships were trained to the questionnaire administration and used as a reference point in case any clarification was required from the single seafarers | Seafarers are exposed to stressful conditions, some inevitably related to their activity (noise, vibrations, interrupted sleep, etc.), and other more subjective (individual capacity to endure loneliness, attitude to resilience, etc.) |

| Rydstedt & Lundh (2010) [38] An Ocean of Stress? The relationship between psychosocial workload and mental strain among engine officers in the Swedish merchant fleet | Quantitative and cross-sectional design | Swedish Merchant Marine Officers’ Association which consists of a total of (n = 731) engine officers in the Swedish merchant fleet. The British comparison sample consisted of (n = 312) professional shore-based engineers | No dimension for PSS10 For JCQ, Demands, Work-related control, decision authority in the work situation and skill variety, work-related social support | Perceived Stress Scale, version 10 (PSS10) and Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) The PSS10 value is 0.84 and the value for JCQ is 0.77 | Lazarus original transactional model and Job Demand Control Model | A questionnaire comprising 129 items was distributed to all engine officers affiliated with the Swedish Merchant Marine Officers’ Association | The main source of the high stress among the engine officers does not seem to be the job content but may rather be understood from an interactional perspective, where conflicting requirements are directed towards the individual officer. |

| An, Liu, Sun, & Liu (2020) [45] Impact of Work–Family Conflict, Job Stress and Job Satisfaction on Seafarer Performance | Quantitative and cross-sectional design | A merchant ship seafarer (n = 337) consisting of officers, engineers, ratings or crew, and catering in the Yangshan Port, Shanghai, China | No specific dimensions, just a list of work-related stress items | Questionnaire survey adapted from the literature The value reported is 0.85 | No theoretical basis | Data gained onboard through the questionnaire. Messages regarding research information were sent from the Port State Control (PSC) to the captains, requesting them to notify seafarers onboard finishing survey forms within the specified time. | Job stress has associated negatively with job performance where it can reduce the performance of the seafarers |

| Håvold (2015) [2] Stress from the bridge of offshore vessels: Examples from the North Sea | Quantitative and cross-sectional design | The sample consists of Norwegian bridge officers (n = 157) working in theNorth Sea on offshore vessels | No specific dimensions, just a list of work-related stress items | Questionnaire survey adapted from the literature The value reported is satisfactory reliability | No theoretical basis | Questionnaire was developed based on a review of the literature and went through the process of checking for reliability and validity. The questionnaire was produced only in the Norwegian language All 40 non-nominal items in the questionnaire | The research shown that age and the length of time do not have any influence on stress and it differs based on the occupation (Between first mate and other navigators). |

| Rengamani & Venkatraman (2015) [25] Study on the job satisfaction of seafarers while on stress predicament | Quantitative and cross-sectional design | Seafarers of Indian origin (n = 385) who were working at various levels/job categories on the deck side and the engine side of foreign-going merchant vessels. The total sample size considered for the study was 385. | No specific dimensions, just a list of work-related stress items | Questionnaire survey constructed for the study The value reported for each item ranges from 0.78 to 0.93 | No theoretical basis | Questionnaire was sent to participants of the target population | The majority of stressors tend to be those associated with psychological and social issues that are related to both personal and work lives. |

| Rengamani & Murugan (2012) [17] A study on the factors influencing seafarers’ stress | Quantitative and cross-sectional design | Indian Seafarers (n = 385) from various levels/job categories on the deck and engine sides of foreign-going merchant vessels. | No specific dimensions, just a list of work-related stressors items | Questionnaire survey constructed for the study The value reported for each item ranges from 0.71 to 0.82 | No theoretical basis | Questionnaire was sent to seafarers of the target population | Important stressors on board are long working days, heat in workplaces, separation from their family, time pressure/ hectic activities, and insufficient qualifications of subordinate crew members. The seafarers who have high stress level because of heat in shipboard operations had shorter job duration at sea. The stressors of heat and noise show that physical stressors on ships currently are still very important in spite of the increasing mechanization in seafaring. |

| Elo (1985) [46] Health and stress of seafarers | Quantitative and cross-sectional design (two phases of study) | Seafarers (n = 591) from the Finnish m merchant fleet. | No specific dimensions, just questions related to stress was used | Questionnaire survey that claimed to be used in another study The value is 0.72 | No theoretical basis | Questionnaire was sent to seafarers while onboard the ship, twice in both of the official languages of Finland (Finnish and Swedish). | Stress results varied for different occupational groups, the engine crew reporting the most stress and found to have problems in connecting with the work environment (i.e., noise, heat). |

| Theme: Physical Stress | Participants | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Weather | 1 | “We are in the ships exposed to weather that cannot be controlled. The weather sometimes could affect our work concentration and rest.” |

| 2 | “Sometimes they are more stressed because of the uncontrolled weather during sailing.” | |

| 22 | “When we are onboard, which could come from changes in the weather, people really affect our motivation to work and concentrate.” | |

| 25 | “During our sailing, sometimes when we are concentrating and excited in working, it suddenly rains, and for that reason, the weather really spoiled us.” | |

| Type of ship Location | 2 | “Seafarers usually work in different ships, so the severity of the stress might differ according to the type of ship and whether they used to work in an LNG ship for a certain contract. If the next contract is with the same type of ship, they might feel less stress because they are used to the environment in that type of ship.” |

| 10 | “We, as seafarers, most of us will not stick to particular ships in working; there are ships which somehow have so much stress due to their management, stress because of co-workers. Every ship is different.” | |

| 14 | “Stress or not actually depends on our management; even the type of ship can influence our stress level; a certain ship like a merchant vessels is a demanding ship which could be stressful for some seafarers.” | |

| 21 | “Type of ship and the management affect seafarers’ stress level.” | |

| 1 | “If we got to work at the port, we actually like working near the land. The environment is easier to accept because they can still see people moving around. Compare this to those who go to sail in the middle of the ocean, far away from land, they can only see the sun, the moon and stars.” | |

| 7 | “Stress levels differ between those who have to work onboard and those who are at the port.” | |

| 17 | “For me, every location is stressful, at the port we are stressed with noise, but we are near land; if on the sea, we are stressed missing family because we are far away.” | |

| 22 | “Every location is stressful depending on how we see it.” | |

| 23 | “I think at the port is quite tiring, but we are near to land, still not far to escape compared to those who are in the middle of the ocean.” | |

| Noise | 6 | “Another stress factor is noise, especially if our rest place is near the engine room, surely, sometimes we can’t rest well.” |

| 13 | “Usually, we cannot sleep well because of noise.” | |

| 23 | “Sometimes just the noise can make us tired and stressed.” | |

| Confined space | 9 | “Yes, stress sometimes feels like we are locked up because of restrictions in the ship, we cannot go anywhere, everything is on the ship, is a confined area.” |

| 11 | “The ship is limited in space. Almost everything we have to share with other crews, sometimes we feel like we need our privacy.” | |

| 12 | “The confined space is stressful like anything, and everything needs to be done within the space. “ | |

| 16 | “In the ship, a lot of things are limited and a bit stress and it is difficult to share many things with the other members.” | |

| 25 | “Confined space is another stress factor among seafarers.” |

| Themes: Personal Issues | Participants | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Character of seafarers | 1 | “The character of seafarers contributes to stress. The more outgoing the person, the more likely they are to have friends compared to those who are not, so if they do not have people to interact with, they might experience stress. Also, the personality of seafarers of an able-to-go tough life will affect how they work on board.” |

| 15 | “I think the first thing in reducing the stress for seafarers, is their own self, their own character.” | |

| 17 | “A good seafarer, who enjoys working, yeah, with less stress, are those who have good character, they enjoy the nature of working as seafarers.” | |

| 21 | “Look at the senior seafarers, those with good character. Most of them rarely stress working onboard, they enjoy it.” | |

| Background of seafarers | 8 | “When I interviewed junior seafarers who applied for jobs, when they said their background is from a rich family, I do not feel confident accepting them, because in the past, seafarers who came from this so-called rich background most of the time can’t retain a seafaring career because it is difficult facing stressful things in this career.” |

| 23 | “A lot of seafarers who experience stress and have mental health issues during work, most cannot cope with the condition because they came from wealthy families.” | |

| 25 | “When the seafarers used to live in a condition of hardship, difficulty, usually they can adapt well to working as seafarers.” | |

| Social status | 1 | “The one who is married might have more stress than the single one.” |

| 8 | “If talking about stress, the most important reason is that they are far away from their family, they miss their family, especially the married ones.” | |

| 9 | “The married seafarers usually stress about if anything happens because the wife has to handle their children alone.” | |

| 14 | “The single one does not have a family; they might not have much stress compared to the married one. The married seafarers usually stress more because they miss their wife and children.” | |

| 15 | “It’s stressful when we have to be far away from our family, especially if they are married.” | |

| Passion | 2 | “The most important thing to have when you work as a seafarer is passion. If they just work as work, they might not really enjoy being a seafarer.” |

| 3 | “The most important thing for work is passion. If not, you cannot go on, you may not enjoy doing the work”. | |

| 10 | “If you don’t have passion, you will feel the work is a burden for you, and you will not happy doing the work.” | |

| 17 | “The old or senior seafarers, if you can ask them, most of them are very passionate, that is why the senior seafarers were rarely involved in over-stressing problems.” | |

| 21 | “If I can say something to those who have the intention to join seafaring, this work needs those who are passionate because the nature of the work is naturally stressful, being in the middle of ocean, far away from family, living in a confined space. If you came work without passion, you cannot survive.” | |

| Awareness | 2 | “The seafarers were still unaware of the stress condition and could not identify if they have a stress-related problem.” |

| 4 | “Sometimes they do not know how to handle it and where to reach when they have a problem, especially related to mental stress, and the level of readiness of the awareness of stress is still less among seafarers.” | |

| 7 | “Stress is something we can’t see although we can feel it. Some people do not know they are actually in a condition of stress, they are actually not aware maybe because they do not know it.” | |

| 8 | “Awareness of stress is important because we could tackle the problem earlier before it worsens.” | |

| 25 | “If the seafarers are always aware and check themselves, take action if needed, this problem of stress could be prevented at an earlier stage.” | |

| Experience | 4 | “Not having much experience can also lead to stress, Not having much preparation, especially for the new workers, will be stressful because we might experience culture shock.” |

| 6 | “Experience could be a factor of stress. Those who are newcomers will usually stress be facing this nature of work for the first few years. If they commit and have passion, after some experience they will get better.” | |

| 17 | “I think stress is normal for those who join this seafaring profession, and after having experiences in this working area, we may understand the work nature and could be better in handling our stress and problems.” | |

| 19 | “Gain as many experiences, slowly we can adapt and enjoy the work, the more experiences, the less the stress.” |

| Theme: Social Living on Board | Participants | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction with people | 1 | “In the old time, more people on the ship, if they have more friends there, the social living on board will be slightly easier. Now we have the technology to handle, so manpower is less with fewer people on board to interact with.” |

| 20 | “It is important for seafarers on board to always interact among them to avoid feeling stressed.” | |

| 22 | “Seafarers onboard area like one family. They should be able to interact and share their problems. This will make them enjoy being there and help them solve the problems.” | |

| 23 | “The social interaction among the crew onboard plays an important role in reducing stress and avoid feeling lonely.” | |

| Fewer social activities | 7 | “Seafarers’ life onboard nowadays compared to the old one. They do not have social activities onboard that could make them closer and also help them reduce the stress of working.” |

| 9 | “It’s kind of boring onboard, especially after finish working of not knowing what to do.” | |

| 21 | “One of the ways that crew in the board can do to reduce their stress from working is to have more social activities among the crew members.” | |

| 25 | “We need to have activities onboard so we can distract ourselves from work routines.” | |

| Cannot escape when facing conflict | 13 | “Conflict between crew will be problematic and stressful because we cannot avoid meeting them because we are on the same ship.” |

| 23 | “Usually, when we are in conflict, the best way is to escape and build some gap. This cannot be done if we are onboard and sure this will be stressful.” | |

| 25 | “If we can, we will try our best to avoid any conflict, especially with our team members, because we cannot escape and run even for a while.” |

| Themes: Technostress | Participants | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Affects concentration | 6 | “Technology like email, and WhatsApp have made us receive an overload of information of work-related things sometimes are tiring and stress.” |

| 7 | “When everything is through technology, we forget sometimes we spend too much on the gadgets even for work purposes, which could affect our health.” | |

| 16 | “Technology helps to spread things easier, like through WhatsApp but sometimes it’s too much, and we can be stressed over it.” | |

| 18 | “We are happy we could contact our family with the technology but sometimes too in contact will make us less focused on work.” | |

| 19 | “Social media really disturb our concentration to do work, and its tiring and stressful.” | |

| Skills deficit | 12 | “The machine thing will help us in certain things, but it may make us less skilled in certain thing.” |

| 15 | “The current seafarers are skilled in technology, but if they ask to complete a certain task manually, sure they cannot do it well.” | |

| 17 | “The stressful thing about technology is we will not have skilful seafarers who can do work manually, let’s say if a machine does not work.” | |

| 22 | “Nowadays seafarers are easy to compare to us, but they are more stressful actually, let’s say when the machine thing cannot operate, they have to do certain skills manually and if they cannot perform well. It could be a problem.” | |

| 24 | “The problem with technology is, yes, to have less skilful seafarers who depend too much on machines.” |

| Themes: Work Factors | Participants | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| No guidance from seniors | 12 | “Seniors always say to us to learn by ourselves, but we sometimes do not know what we do is right or not, they don’t guide us properly.” |

| 13 | “I think if we get proper guidance from the senior, we could do work fast with less stress.” | |

| 16 | “Yes, knowledge is important, but sometimes certain problem is beyond us knowledge, we need to seek advice from senior. There is a senior willing to help, there is also those who ignores us.” | |

| 24 | “Cooperation between junior and senior seafarers are important to ensure the work can be done better, senior who have more experience will help juniors who just came in.” | |

| Workload | 3 | “The workload is high and sometimes we don’t get the proper rest.” |

| 4 | “The workload also increases. Sometimes we have been given work or tasks out of our job scope.” | |

| 21 | “The thing is, top management increased our workload, I thought with technology manpower is reduced, and we will not have to stress of workload problem, but we need to do more other things like paperwork.” | |

| 22 | “High workload means high stress.” | |

| Treatment of the employer | 17 | “I think there is unfair treatment from the top management that makes some seafarers stress and do not want to continue in their career.” |

| 19 | “I remember I worked with this company, and very good treatment I got; sometimes a stressful task can be enjoyed because they help us and treat us better.” | |

| 21 | “When we make a complaint and tell our concern to the top management, it is disappointing somehow, they ignore our concerns and complaints.” | |

| 23 | “If the top management care for a need and welfare of seafarers, surely the stress things could be reduced among them.” | |

| Job security | 5 | “Most of the jobs in seafaring are contract basis. They do not know is they will get another contract if they finish a certain contract.” |

| 6 | “The major concern among seafarers is actually about job security, which affects their performance, we could stress thinking of not being secure for a certain job.” | |

| 7 | “Job security is always a problem among seafarers, it is normal if they feel stress working and no guarantee for it.” | |

| 22 | “Job security is an issue that needs to be settled for seafarers.” | |

| 24 | “Yes, when we are not secure for a job, we are stressed because we need money to survive and to feed our family.” | |

| Working hours | 3 | “They did not follow the stated working hours and forced us to work at any time.” |

| 4 | “Long working hours sometimes could be stressful.” | |

| 6 | “Although seafarers have standard working hours, we do not follow them. We work more and do not have enough rest time.” | |

| 9 | “Yes, long working hours are stressful.” | |

| 11 | “Because we cannot move anywhere, confined in a ship, sometimes we need to work after the stated working hours and sometimes bring us stress, we cannot escape from the ship.” | |

| 15 | “Top management always say only work during working hours, but in reality, when we are on the ship, we work more than that.” | |

| Wages | 1 | “Many seafarers are unsatisfied with the wage scale and all that.” |

| 16 | “Seafarers, most of them are not satisfied with the wages scale.” | |

| 18 | “The problem of wages needs to be settled, which can reduce stress among seafarers.” | |

| 20 | “Wages always took time to be paid. Sometimes we need the money urgently.” | |

| 21 | “Earning money is the main thing when we are working, if it’s a problem for sure we will feel stressed.” |

| Themes: COVID-19 Pandemic | Participants | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Travel restriction | 8 | “The travel restriction during covid19 is stressful. At the beginning, we are stuck, and missing our family.” |

| 9 | “I still remember when the lockdown happened, we could not go anywhere. It was restricted and so much stress during the time.” | |

| 10 | “Everybody was stressed when we are restricted from going anywhere.” | |

| 14 | “Yes, the pandemic was stressful, especially during the early lockdown. We were somehow stuck did not know what to do, and could not go anywhere.” | |

| 21 | “It was stressful because we were stuck, could not travel back to meet family for months.” | |

| 24 | “The COVID-19 was historical and stressful, cannot go anywhere, and we were separate from family and could not do anything.” | |

| 25 | “When the Prime Minister announced the lockdown and travel restriction, we were shocked and went through a very hard time.” | |

| Getting unpaid | 2 | “This COVID-19 is really stressful, especially when you don’t get paid.” |

| 3 | “One problem for seafarers during this pandemic is they did not get their pay because they were stuck and could not sign in.” | |

| 4 | “Another effect of this COVID-19 is if we are stuck at home, we cannot go to work, and will not get paid.” | |

| 6 | “When there is no sign in sign off, we cannot work, and our money is reducing. That was very stressful” | |

| 22 | “The travel restriction during the pandemic, especially for the first few months, was really stressful for us, we cannot go to work and get money for our family.” | |

| 25 | “I feel so much stress because I had no money to give to the family and was stuck at home.” | |

| Uncertainty | 1 | “Because of this pandemic, seafarers now do not know whether they can secure a job or not.” |

| 20 | “So many uncertainties thinking of our work.” | |

| 21 | “During the MCO, we were so much worry and stress because everything was uncertain, start with not sure when to sign in sign off to our work contract, whether we can continue working or not.” | |

| Double standard quarantine | 4 | “Some people are not given fair period for the quarantine. There are people who can just quarantine for three days and some need to quarantine for fourteen days.” |

| 7 | “There is unfairness in the quarantine period for certain people they do not follow quarantine period of fourteen days.” | |

| 8 | “We have to pay for quarantine ourselves, which was stressful.” | |

| 9 | “It was such a stressful experience when we had to quarantine for 14 days, and there are some people have to quarantine less than that.” | |

| Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) restrictions | 6 | “Standard operating procedure (SOP) made us stressed, many things to do and sometimes tiring.” |

| 7 | “SOP comes with many rules need to follow, its stressful.” | |

| 11 | “I remember during the covid19 phase, we are not only stressed because cannot go anywhere, no income, but we stress because of SOP things.” | |

| 12 | “I feel somehow the SOP is nonsense sometimes and tiring.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, S.N.M.; Cioca, L.-I.; Kayati, R.S.; Saputra, J.; Adam, M.; Plesa, R.; Ibrahim, R.Z.A.R. A Study of Psychometric Instruments and Constructs of Work-Related Stress among Seafarers: A Qualitative Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042866

Ali SNM, Cioca L-I, Kayati RS, Saputra J, Adam M, Plesa R, Ibrahim RZAR. A Study of Psychometric Instruments and Constructs of Work-Related Stress among Seafarers: A Qualitative Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042866

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Siti Nazilah Mat, Lucian-Ionel Cioca, Ruhiyah Sakinah Kayati, Jumadil Saputra, Muhammad Adam, Roxana Plesa, and Raja Zirwatul Aida Raja Ibrahim. 2023. "A Study of Psychometric Instruments and Constructs of Work-Related Stress among Seafarers: A Qualitative Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042866

APA StyleAli, S. N. M., Cioca, L.-I., Kayati, R. S., Saputra, J., Adam, M., Plesa, R., & Ibrahim, R. Z. A. R. (2023). A Study of Psychometric Instruments and Constructs of Work-Related Stress among Seafarers: A Qualitative Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042866