The Price of Growing Up in a Low-Income Neighborhood: A Scoping Review of Associated Depressive Symptoms and Other Mood Disorders among Children and Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Neighborhoods and Mental Health

1.1.2. Past Reviews

- Is neighborhood poverty/gentrification associated directly or indirectly with the prevalence and symptoms of mood disorders among children and adolescents?

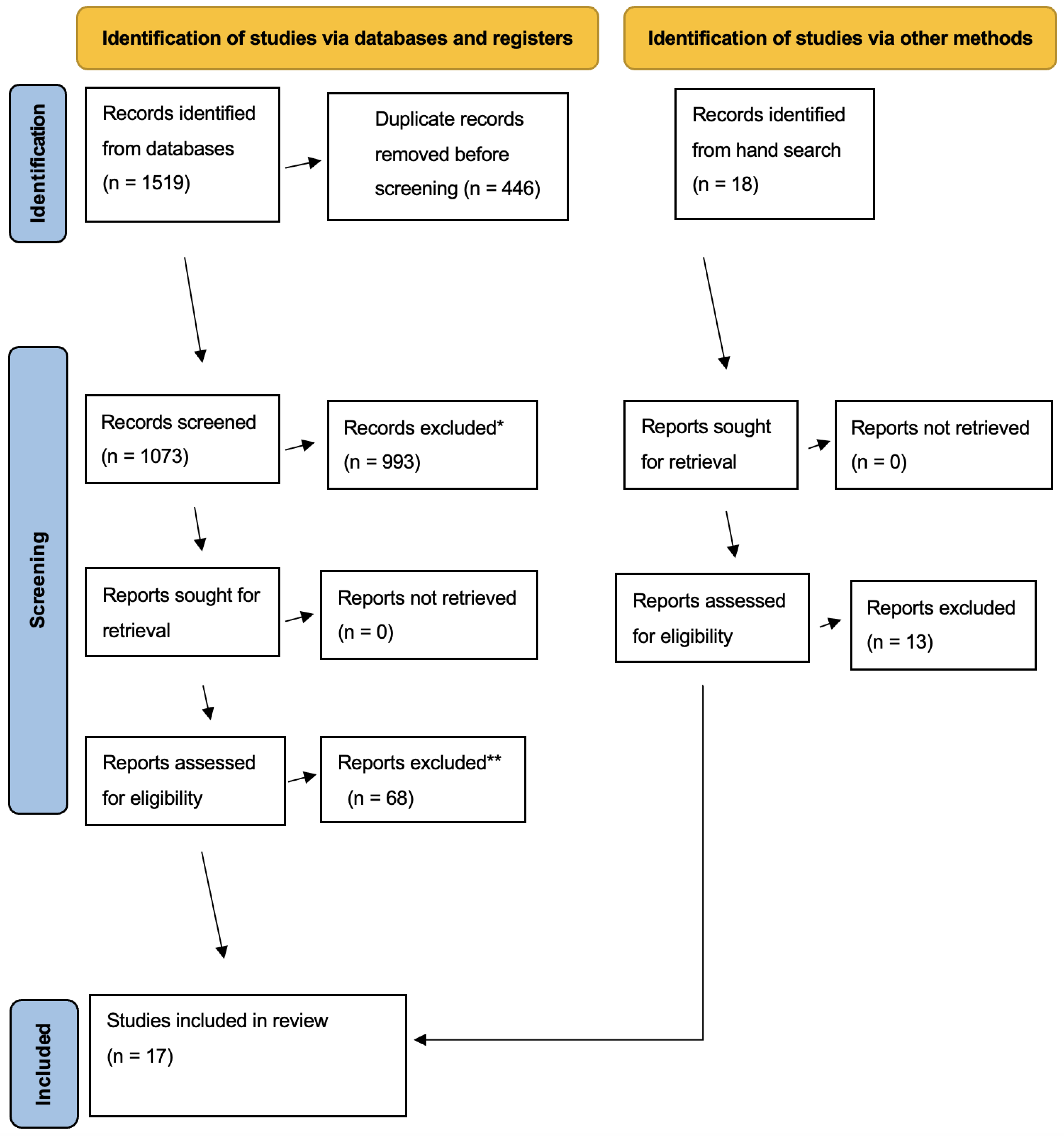

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Criteria for Study Selection

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Neighborhood Poverty and Gentrification Measures

3.3. Depression/Depressive Symptoms

3.4. Significance of Results

3.4.1. Children

3.4.2. Adolescents

3.4.3. Children and Adolescents

3.5. Significant Mediation/Moderation

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Basis

4.1.1. Neighborhood Measures

4.1.2. Depression Measures

4.1.3. Statistical Analyses

4.2. Theoretical Basis

4.2.1. Life-Course Theory

4.2.2. Ecological Systems Model and Ecosocial Theory

4.3. Implications

4.3.1. Policy

4.3.2. Clinical Services

4.3.3. Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First Author | Year | Sample Size | Data Source and Population £ | Study Design | Neighborhood Poverty or Gentrification | Depression Outcome † | Results | Coefficients and Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegria | 2019 | 2491 | Boricua Youth Study Puerto Rican children (5-13 years old) | Longitudinal | Neighborhood context: Proportion of people living below the poverty line, percentage of female-led households, and percentage of Latine households | CIDI (with self-reported Major Depressive Disorder) and DAS | Neighborhood poverty indicators mediated the relationship between minority status and Major Depressive Disorder diagnosis. Neighborhood poverty indicators were not included in the full model. | Proportion of female-headed households with child under 18 significantly mediated (b = 0.22, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001) the relationship between minority status and mental health outcomes. |

| Dearing ‡ | 2001 | 206 | Data from four Boston elementary schools Children (7-8 years old) | Longitudinal | Neighborhood Quality: 1990 Census neighborhood percentage of people living in poverty and reported crime rate for that neighborhood | Reynold’s Depression Scale | Increases in neighborhood quality led to decreases in childhood depression in waves one and two but not three. | Wave 1 (b = -0.19, SE = NR, p < 0.01) Wave 2 (b = −0.31, SE=NR, p < 0.01) Wave 3 non-significant |

| Xue | 2005 | 2805 | Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods Children (5-11 years old) | Longitudinal | Concentrated neighborhood disadvantage: Neighborhood poverty rate, percentage of residents receiving public assistance, percentage of female-headed families, unemployment ratio, and percentage of African American residents | CBLC/4-18 and then an additional dichotomized clinical threshold variable | Concentrated disadvantage was associated with more mental health problems and a higher number of children in the clinical range. Collective efficacy mediated the effect of concentrated disadvantage. Once collective efficacy was added to the model, concentrated disadvantage was no longer directly significant. | ICC= 11.1%. Concentrated disadvantage for total raw score (b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p < 0.01) and dichotomous clinical threshold (LO = 0.19, SE = 0.09, p < 0.05) |

| Caughy | 2003 | 200 | Data from Baltimore urban center Black children (3-4 years old) | Cross-sectional | Neighborhood Impoverishment: Neighborhood poverty rate, unemployment rate, vacant housing rate | CBLC/2-3 and CBLC/4-18 | Low-income neighborhoods were associated with higher internalizing problems among children compared to other quartile neighborhoods. Rate of total problem behaviors and internalizing behaviors for children living in neighborhoods in the lowest quartile of impoverishment was higher if their mothers knew very few neighbors. | Lowest income quartile neighborhood (F = 3.57, DF = NR, p < 0.05) and mothers’ high social capital significantly interacted with/strengthened the relationship between neighborhood income and child internalizing behaviors |

| Li | 2007 | 263 | Data on eight Chicago elementary schools Children (8-9 years old) | Cross-sectional | Neighborhood Poverty: Census block groups | Average of CDI, HIF, and CBLC parent report form | Relationship between neighborhood poverty and children’s internalizing symptoms was not significant. | Non-significant |

| Schaefer-McDaniel | 2009 | 126 | Data on three New York neighborhoods Children | Cross-sectional | Neighborhood Social Disorder: Systematic Social Observations inventory with two independent raters | CDI | No significant direct relationship between neighborhood social disorder and childhood depression, but child subjective evaluations of neighborhood quality fully mediated the relationship between drug/alcohol stressors and childhood depression. | Non-significant |

| Simons | 2002 | 867 | Data from Iowa and Georgia Family and Community Health Study Black children (10–12 years old) | Cross-sectional | Neighborhood Poverty: Census block data on proportion of households below the poverty line in each block group | DISC-IV | No significant direct relationship between neighborhood poverty and child depressive symptoms, but neighborhood poverty significantly moderated the relationship between being the victim of a crime and child depressive symptoms. | ICC = NR Living in a high poverty neighborhood significantly interacted with/strengthened the relationship between being the victim of a crime and child depressive symptoms (b = −0.24, SE = NR, p < 0.05) |

| First Author | Year | Sample Size | Data Source and Population £ | Study Design | Neighborhood Poverty or Gentrification | Depression Outcome † | Results | Coefficients and Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rudolph | 2017 | 1094 | Moving to Opportunity data Black and Latino adolescent males | Experimental ⸹ | Moving from a low-poverty neighborhood: Residents living in high poverty census tracts within five U.S. cities were randomly allocated housing vouchers to relocate away from high poverty neighborhoods. | Major Depressive Disorder according to DSM | Cities had similar rates of depression and moving did not give definitive results. | Housing voucher receipt increased risk of major depressive disorder among boys in New York City but decreased risk in Chicago (p-value for site difference = 0.10) |

| Donnelly | 2016 | 2264 | The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study Adolescents (born 1998–2000) | Longitudinal | Neighborhood SES: Census data on percentages of residents who were poor, unemployed, and receiving public assistance and of residents without a high school diploma and with a bachelor’s degree; the percentage of workers with professional or managerial occupations; and percentage of households headed by a female | CES-D | Non-significant, but neighborhood collective efficacy improved mental health. | Non-significant |

| Hurd | 2013 | 571 | Sample from four high-schools in a midwestern state Black adolescents | Longitudinal | Neighborhood Poverty Rate: Census block group on percent of African American residents, householders living in the same house for over 5 years, families living below the poverty line (poverty rate), and residents over the age of 16 unemployed | Part of the Brief Symptom Inventory | Adolescents in more impoverished neighborhoods reported lower total levels of social support. Lower levels of social support mediated the relationship between neighborhood poverty and depressive symptoms. Neighborhoods with a higher unemployment rate were associated with lower perceptions of neighborhood cohesion. | ICC = 5% Neighborhood poverty rate to social support had a significant indirect effect on depressive symptoms path a: (b = −1.02, SE = 0.45, p < 0.05) and path b: (b = −0.32, SE = 0.14, p < 0.05) Neighborhood unemployment to perceived neighborhood cohesion had a significant indirect effect on depressive symptoms, path a: (b = −0.48, SE = 0.22, p < 0.05) path b: (b = −0.20, SE = 0.09, p < 0.05) |

| Wickrama | 2005 | 20,745 | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) Adolescents | Longitudinal | Poverty Concentration Index: Comprised of the proportion of families living in poverty, single-parent families, adults employed in service occupations, and unemployed males | CES-D | Only the interactions between race and community disadvantage were significantly related to CES-D scores among adolescents. | ICC = 14% Significant interactions between race and community disadvantage on CES-D |

| Aneshensel | 1996 | 877 | Data from Los Angeles Neighborhoods Adolescents | Cross-sectional | Neighborhood SES Index | CDI | Latine adolescents in low-income neighborhoods had higher depression CDI scores, except when they lived in neighborhoods with a high concentration of Latine populations. | Majority ethnicity Latine, low-income neighborhoods (b = −0.418, SE = 0.17, p < 0.05) Other neighborhoods non-significant |

| Wickrama | 2003 | 14,500 | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) Adolescents | Cross-sectional | Community poverty concentration: Census tract level proportion of families living in poverty, single-parent families, adults employed in service occupations, and proportion of unemployed men | CES-D | Without individual variables, concentration of poverty strongly predicted adolescent depressive symptoms, but after adding individual and school characteristics, it was no longer significant. The sample was also split into “less adverse” and “extreme adverse communities”; in less adverse communities, concentration of poverty predicted depressive symptoms. | ICC = NR Model 1(b = 2.35, SE = NR, p < 0.001), Model 2 (b = 0.62, SE = NR, p < 0.05) Models 3–5: Non-significant Concentration of poverty significant in less adverse communities (b = 5.18, SE = NR, p < 0.05) but non-significant in extreme adverse communities |

| First Author | Year | Sample Size | Data Source and Population £ | Study Design | Neighborhood Poverty or Gentrification | Depression Outcome † | Results | Coefficients and Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leventhal | 2003 | 512 | Re-interview of the Moving to Opportunity participants Children and Adolescents (8–18 years old) | Experimental ⸹ | Neighborhood Poverty: Census block data on poverty concentration (comprised of median incomes, fraction of residents in poverty, and fraction of rental units) | Behavioral problem index (anxious/ depressive scales) | Boys who moved to less poor neighborhoods reported significantly fewer anxious/depressive and dependency problems than did boys who stayed in low-income neighborhoods and boys in public housing. Children aged 8–13 reported significantly fewer anxious/depressive symptoms compared to children who stayed in low-income neighborhoods and children in Section 8 Housing. | Boys who moved (experimental group) in comparison to families who stayed in low-income neighborhoods (b = −0.42, SE = 0.21, p < 0.01) and in comparison to families in Section 8 housing (b = −1.20, SE = 0.65, p < 0.05) Children 8–13 years old in families that moved compared to families that stayed in low-income neighborhoods (b = −0.39, SE = 0.21, p < 0.05) and compared to families in Section 8 Housing (b = −0.90, SE = 0.49, p < 0.05) |

| Patrick ‡ | 2019 | 618 | Project on Human Development Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) Black and Latine children and adolescents | Longitudinal | Neighborhood Concentrated Poverty Index: The percentage of poor families, percentage of single parent families, percentage of families receiving public assistance, and unemployment rate | Self-endorsed depressive/ anxiety symptoms | Increases in concentrated poverty significantly predicted self-endorsed depression/anxiety symptoms among all adolescents and male children in one model, but the latter relationship was not significant for male children once other individual factors (i.e., discrimination) were added. | For adolescents (b = 1.06, SE = 0.48, p < 0.05). For male children in one model (b = 1.28, SE = 0.56, p < 0.05) but non-significant for female children. |

| Delany-Brumsey ‡ | 2012 | 1305 | Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A. FANS) Children and Adolescents | Cross-sectional | Neighborhood SES Disadvantage: Percentage of population in poverty, families with an annual income less than $24,000, households headed by females with children, households receiving public assistance, non-White and non-Asian and Pacific Islander, and under age 18 | Behavioral problem index (including anxiety and depression subscales) | The level of neighborhood disadvantage was associated with children’s behavioral problems, but it was not significantly associated with either internalizing or externalizing behavior problems in adolescents. | ICC = 12% Disadvantaged neighborhoods (b = 0.51, SE = 0.16, p < 0.01). When maternal depression interaction term is included in the model, greater neighborhood economic disadvantage is associated with more behavior problems for adolescents internalizing (b = 0.46, p < 0.05). |

| Dragan | 2019 | 71,835 | New York Medicaid Data Set Children and Adolescents (born 2006–2008) | Cross-sectional | Gentrifying Neighborhoods: Bottom 40% of city tract neighborhoods that experienced growth in waves subsequent to baseline | Depression/ anxiety: Not stated, but likely was a self-reported diagnosis | There was a significant increase in depression or anxiety among adolescents in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood compared to those that remained in low SES areas | Children in areas that gentrified had a 22% higher prevalence of depression/anxiety than children in low-SES areas. There was a 1.56% increase (8.69% versus 7.13%) in depression/anxiety in rapidly gentrifying areas compared to those who remained in low SES neighborhoods |

References

- Artiga, S.; Hinton, E. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. Health 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R.; Pamuk, E. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health in the United States: What the Patterns Tell Us. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S186–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.J. Social Determinants of Health Equity. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, S517–S519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-K.; Kelley, M.; Wang, D.; Kerby, H. Neighborhood Environment and Child Health in Immigrant Families: Using Nationally Representative Individual, Family, and Community Datasets. Am. J. Health Promot. 2021, 35, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-C.; South, S.J. Neighborhood Poverty and Physical Health at Midlife: The Role of Life-Course Exposure. J. Urban Health 2020, 97, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social Determinants of Mental Health. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506809 (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Dawson, C.T.; Wu, W.; Fennie, K.P.; Ibañez, G.; Cano, M.; Pettit, J.W.; Trepka, M.J. Parental-perceived neighborhood characteristics and adolescent depressive symptoms: A multilevel moderation analysis. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 1568–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, J.R.; Horel, S.; Han, D.; Huber, J.C. Association between neighborhood need and spatial access to food stores and fast food restaurants in neighborhoods of Colonias. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2009, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, T.P.; Buck, P.W. Childhood and Adolescent Neighborhood Effects on Adult Income: Using Siblings to Examine Differences in Ordinary Least Squares and Fixed-Effect Models. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2005, 79, 60–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cubbin, C.; Kim, Y.; Vohra-Gupta, S.; Margerison, C. Longitudinal measures of neighborhood poverty and income inequality are associated with adverse birth outcomes in Texas. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 245, 112665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.P.; Wang, L.; Elliott, M.R. Investigating the relationship between neighborhood poverty and mortality risk: A marginal structural modeling approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 91, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Jung, H.; Jaime, J.; Cubbin, C. Is neighborhood poverty harmful to every child? Neighborhood poverty, family poverty, and behavioral problems among young children. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 47, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, C.; Powers, D.; Margerison-Zilko, C.; McDevitt, T.; Cubbin, C. Historical neighborhood poverty trajectories and child sleep. Sleep Health 2018, 4, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, A.V.D. Investigating Neighborhood and Area Effects on Health. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 1783–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Neighborhoods and Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-19-974792-4. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S.; Chen, J.T.; Rehkopf, D.H.; Waterman, P.D.; Krieger, N. Racial Disparities in Context: A Multilevel Analysis of Neighborhood Variations in Poverty and Excess Mortality Among Black Populations in Massachusetts. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, I.H.; Michael, Y.L.; Perdue, L. Neighborhood Environment in Studies of Health of Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubbin, C.; Heck, K.; Powell, T.; Marchi, K.; Braveman, P. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Depressive Symptoms Among Pregnant Women Vary by Income and Neighborhood Poverty. AIMS Public Health 2015, 2, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.; Gotanda, N.; Peller, G.; Thomas, K. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement; The New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-1-56584-271-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dixson, A.D.; Rousseau, C.K. And we are still not saved: Critical race theory in education ten years later. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorzano, D.; Ceja, M.; Yosso, T. Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate: The Experiences of African American College Students. J. Negro Educ. 2000, 69, 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, M. Grieving for a lost home: The psychological costs of relocation. In The Urban Condition: People and Policy in the Metropolis; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, K.S.; Hagemans, I.W. ‘Gentrification Without Displacement’ and the Consequent Loss of Place: The Effects of Class Transition on Low-income Residents of Secure Housing in Gentrifying Areas. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project 2015. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/09/28/modern-immigration-wave-brings-59-million-to-u-s-driving-population-growth-and-change-through-2065/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Aaronson, D.; Mazumder, B.; Hartley, D.A.; Harrison Stinson, M. The Long-Run Effects of the 1930s Redlining Maps on Children; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, B.; Franco, J. HOLC “Redlining” maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality. Home Owners’ Loan Corporation “Redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality. 2018. Available online: https://dataspace.princeton.edu/handle/88435/dsp01dj52w776n (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Massey, D.; Denton, N. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 170–181. ISBN 978-0-429-49446-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J.S.; Shandas, V.; Pendleton, N. The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat: A Study of 108 US Urban Areas. Climate 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America; Liveright Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Menendian, S.; Arthur, G.; Gambhir, S. The Roots of Structural Racism Project: Twenty-First Century Racial Residential Segregation in the United States; Othering & Belonging Institute: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C.J.; Abraham, J.; Ali, M.K.; Alvarado, M.; Atkinson, C.; Baddour, L.M.; Bartels, D.H.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bhalla, K.; Birbeck, G. The state of US health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013, 310, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, H.; Curtin, S.C.; Warner, M. Suicide Rates in the United States Continue to Increase. NCHS Data Brief 2018, 309, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Wallace, G.; Wesner, K.A. Neighborhood Characteristics and Depression. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, V.S.; Mahadevan, R.; Leung, J. Effect of income inequality, community infrastructure and individual stressors on adult depression. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 36, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, J.C. The development of an instrument to measure neighborhood cohesion. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1988, 16, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.V. Neighborhood quality and somatic complaints among American youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 36, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, N.L.; Quinless, F.W.; Parietti, E.S. Assessment of a Newark Neighborhood: Process and Outcomes. J. Community Health Nurs. 2000, 17, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Cooper, H.L.; Drews-Botsch, C.D.; Waller, L.A.; Hogue, C.R. Metropolitan isolation segregation and Black–White disparities in very preterm birth: A test of mediating pathways and variance explained. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.C. The Mechanism(s) of Neighbourhood Effects: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications BT—Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives. In Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives; van Ham, M., Manley, D., Bailey, N., Simpson, L., Maclennan, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 23–56. ISBN 978-94-007-2309-2. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, A.; Muhajarine, N.; Janus, M.; Brownell, M.; Guhn, M. A review of neighborhood effects and early child development: How, where, and for whom, do neighborhoods matter? Health Place 2017, 46, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.A.; Comey, J.; Kuehn, D.; Nichols, A. Helping Poor Families Gain and Sustain Access to High-Opportunity Neighborhoods; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria, M.; Shrout, P.E.; Canino, G.; Alvarez, K.; Wang, Y.; Bird, H.; Markle, S.L.; Ramos-Olazagasti, M.; Rivera, D.V.; Cook, B.L.; et al. The effect of minority status and social context on the development of depression and anxiety: A longitudinal study of Puerto Rican descent youth. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. (WPA) 2019, 18, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aneshensel, C.S.; Sucoff, C.A. The Neighborhood Context of Adolescent Mental Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1996, 37, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caughy, M.O.; O’campo, P.J.; Muntaner, C. When being alone might be better: Neighborhood poverty, social capital, and child mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dearing, E.C. Parenting and Child Competence: A Longitudinal Investigation of the Moderating Influences of Ethnicity, Family Socioeconomic Status, and Neighborhood Quality; ProQuest Information & Learning: Ann Harbor, MI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Delany-Brumsey, A. Capitalizing on Place: An Investigation of the Relationships among Social Capital, Neighborhood Conditions, Maternal Depression, and Child Outcomes; ProQuest Information & Learning: Ann Harbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, L.; McLanahan, S.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Garfinkel, I.; Wagner, B.G.; Jacobsen, W.C.; Gold, S.; Gaydosh, L. Cohesive Neighborhoods Where Social Expectations Are Shared May Have Positive Impact On Adolescent Mental Health. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 2083–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, K.L.; Ellen, I.G.; Glied, S.A. Gentrification And The Health Of Low-Income Children In New York City. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, N.M.; Stoddard, S.A.; Zimmerman, M.A. Neighborhoods, Social Support, and African American Adolescents’ Mental Health Outcomes: A Multilevel Path Analysis. Child Dev. 2012, 84, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, T.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Moving to Opportunity: An Experimental Study of Neighborhood Effects on Mental Health. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.T.; Nussbaum, K.M.; Richards, M.H. Risk and protective factors for urban African-American youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, A.A. The Effect of Racial Discrimination on Mental Health of African American and Hispanic American Adolescents; ProQuest Information & Learning: Ann Harbor, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, K.E.; Schmidt, N.M.; Glymour, M.M.; Crowder, R.; Galin, J.; Ahern, J.; Osypuk, T.L. Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives. Epidemiology 2018, 29, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer-McDaniel, N. Neighborhood stressors, perceived neighborhood quality, and child mental health in New York City. Health Place 2009, 15, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Murry, V.; Mcloyd, V.; Lin, K.-H.; Cutrona, C.; Conger, R.D. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Dev. Psychopathol. 2002, 14, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickrama, K.; Noh, S.; Bryant, C.M. Racial differences in adolescent distress: Differential effects of the family and community for blacks and whites. J. Community Psychol. 2005, 33, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickrama, K.A.S.; Bryant, C.M. Community Context of Social Resources and Adolescent Mental Health. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Leventhal, T.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Earls, F.J. Neighborhood Residence and Mental Health Problems of 5- to 11-Year-Olds. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.J.; Bertino, M.D.; Bailey, C.M.; Skewes, J.; Lubman, D.I.; Toumbourou, J.W. Depression and suicidal behavior in adolescents: A multi-informant and multi-methods approach to diagnostic classification. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, P.E.; Sebastian, M.S.; Janlert, U.; Theorell, T.; Westerlund, H.; Hammarström, A. Life-Course Accumulation of Neighborhood Disadvantage and Allostatic Load: Empirical Integration of Three Social Determinants of Health Frameworks. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N. Methods for the Scientific Study of Discrimination and Health: An Ecosocial Approach. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Doucouliagos, H.; Manning, E. Does education reduce income inequality? a meta-regression analysis. J. Econ. Surv. 2013, 29, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.B. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; p. 384. ISBN 9780674504769. [Google Scholar]

- Shaefer, H.L.; Edin, K. Rising Extreme Poverty in the United States and the Response of Federal Means-Tested Transfer Programs. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2013, 87, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reeves, A.; McKee, M.; Mackenbach, J.; Whitehead, M.; Stuckler, D. Introduction of a National Minimum Wage Reduced Depressive Symptoms in Low-Wage Workers: A Quasi-Natural Experiment in the UK. Health Econ. 2016, 26, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau; CensusGov. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Eggleston, J.; Hays, D.; Munk, R.; Sullivan, B. The Wealth of Households, 2017; US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, A.; Ray, R.; Brookings. Why we need reparations for Black Americans. 2020. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/bigideas/why-we-need-reparations-for-black-americans/ (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Laremont, R.R. Jewish and Japanese American Reparations: Political Lessons for the Africana Community. J. Asian Am. Stud. 2001, 4, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; Valls, A. Housing Discrimination as a Basis for Black Reparations. Public Aff. Q. 2007, 21, 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gariepy, G.; Blair, A.; Kestens, Y.; Schmitz, N. Neighbourhood characteristics and 10-year risk of depression in Canadian adults with and without a chronic illness. Health Place 2014, 30, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, R. Evaluating the Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program’s Effect on Neighborhoods. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, San Diego, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, P.J.; Zhu, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Polsky, D.; Bishop, T.F.; Seirup, J.K.; Pincus, H.A.; Ross, J.S.; Olfson, M.; McGinty, E.E.; et al. Beyond Parity: Primary Care Physicians’ Perspectives On Access To Mental Health Care. Health Aff. 2009, 28, w490–w501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, S.; Brown, J.S.L.; Davey, C.G. Editorial: Early Intervention in Mood Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 799941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, T.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Ayers, C.; Murdoch, J.C.; Yin, W.; Pruitt, S.L. Property Values as a Measure of Neighborhoods. Epidemiology 2016, 27, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cohen, M.; Pettit, K.L.S. Guide to Measuring Neighborhood Change to Understand and Prevent Displacement; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De la Roca, J.; Ellen, I.G.; O’Regan, K.M. Race and neighborhoods in the 21st century: What does segregation mean today? Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2014, 47, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, T.A.; Woodward, A.J. Ecological effects in multi-level studies. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, U.; Franco, M.; Lau, B.; Celentano, D.; Glass, T. Measuring neighbourhood social and economic change for urban health studies. Urban Stud. 2019, 57, 1301–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.A.; McArdle, J.J.; Hishinuma, E.S.; Johnson, R.C.; Miyamoto, R.H.; Andrade, N.N.; Edman, J.L.; Makini, G.K.; Nahulu, L.B.; Yuen, N.Y.; et al. Prediction of Major Depression and Dysthymia From CES-D Scores Among Ethnic Minority Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 37, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, M.E.; Hudziak, J.J.; Heath, A.C.; Achenbach, T.M. Latent Class Analysis of Child Behavior Checklist Anxiety/Depression in Children and Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wood, B.M.; Cubbin, C.; Rubalcava Hernandez, E.J.; DiNitto, D.M.; Vohra-Gupta, S.; Baiden, P.; Mueller, E.J. The Price of Growing Up in a Low-Income Neighborhood: A Scoping Review of Associated Depressive Symptoms and Other Mood Disorders among Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196884

Wood BM, Cubbin C, Rubalcava Hernandez EJ, DiNitto DM, Vohra-Gupta S, Baiden P, Mueller EJ. The Price of Growing Up in a Low-Income Neighborhood: A Scoping Review of Associated Depressive Symptoms and Other Mood Disorders among Children and Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(19):6884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196884

Chicago/Turabian StyleWood, Bethany M., Catherine Cubbin, Esmeralda J. Rubalcava Hernandez, Diana M. DiNitto, Shetal Vohra-Gupta, Philip Baiden, and Elizabeth J. Mueller. 2023. "The Price of Growing Up in a Low-Income Neighborhood: A Scoping Review of Associated Depressive Symptoms and Other Mood Disorders among Children and Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 19: 6884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196884

APA StyleWood, B. M., Cubbin, C., Rubalcava Hernandez, E. J., DiNitto, D. M., Vohra-Gupta, S., Baiden, P., & Mueller, E. J. (2023). The Price of Growing Up in a Low-Income Neighborhood: A Scoping Review of Associated Depressive Symptoms and Other Mood Disorders among Children and Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(19), 6884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196884