First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples Living in Urban Areas of Canada and Their Access to Healthcare: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples

1.2. The Migration of Indigenous People to Urban Areas

1.3. Access to Health Services in Urban Areas of Canada

1.4. Aim

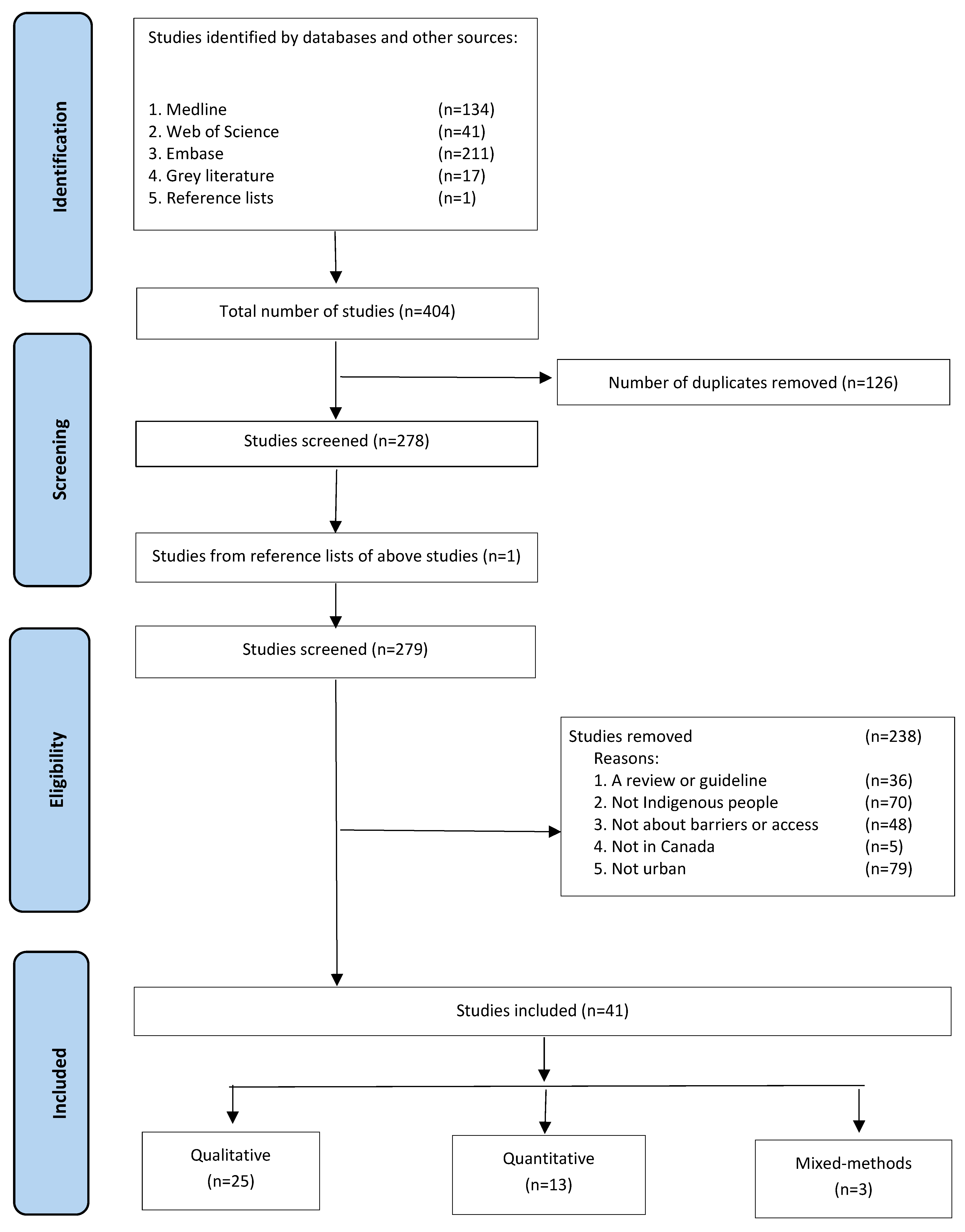

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conducting the Review

2.2. Search Strategy

- (First Nations OR Inuit OR Métis OR Indigenous OR Aboriginal OR Native) AND

- (Canada) AND

- (Urban OR urbanized OR city OR cities OR metropolitan) AND

- (clinic OR medical OR doctor OR nurse OR physician OR primary health service OR mental health OR hospital OR drug use services) AND

- (access OR accessing)

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Barriers of Accessing Health Services

3.2.1. Difficult Communication with Health Care Professionals

This time it was not as bad because my daughter came with me. I felt I was treated alright… I felt this time around the staff treated me good and this time I understand as the doctor talked slow to me and when I don’t understand the question I asked him to explain it to me better. I feel more comfortable now.[53]

The doctor himself is so abrasive—flies into the room, does what he needs to do … it doesn’t really seem like he cares, and he is out the door and on to the next patient. … I feel so rushed that I don’t actually get to talk about things that are pertinent to my pregnancy. And so I leave the office and did not voice my concerns.[27] (p. 5)

3.2.2. Medication Issues

3.2.3. Dismissal or Discharge by Healthcare Staff

My pneumonia hadn’t even [gone away] and it was during winter time. And …one of the nurses came in and said the doctor is discharging you. I said I’m not even better yet and she said, well it’s time for you to go … don’t let me call security. And sure enough she called security. Security literally came in, grabbed me behind my arms, dragged me down the hallways and threw me out the door, with pneumonia, in winter time.[16] (p. 1112)

3.2.4. Wait Times

I notice every time I go see a doctor, I’m waiting for a long time. Like my knee, I handled that for about a week and a half before I even decided to go [for treatment] because I knew the waiting time was just going to be a long time.[42] (p. 705)

3.2.5. Mistrust and Avoidance of Healthcare

Sometimes we don’t trust the doctors … because we don’t know what they’re going to give us. And sometimes that can harm our body … That’s why when I was smoking and I was coughing for three days, I didn’t go to the hospital because I’m scared of hospitals. Sometimes it’s trust.[39] (p. 871)

3.2.6. Racial Discrimination

The healthcare workers treated me like crap and I know it was because I was Native … When you need the medical care we put up with it. We shouldn’t have to.[20]

3.2.7. Poverty and Transportation

… you have to expect living in this area you’re not going to get the best healthcare. It seems like they care less when you‘re in a poverty-stricken area … the doctor’s office is kind of ghetto looking … It doesn’t feel personable, it doesn’t feel welcoming, and it feels like you’re in and out, and they are not doing their job. They don’t ask you how you’re doing, as they would in a different nicer area.[47]

“I was supposed to go for an ultrasound, but I couldn’t go. It was cold that day and I wasn’t gonna walk. I didn’t have a bus fare … didn’t want to freeze my ears, so I just stayed home”.[27]

3.3. Facilitators of Accessing Health Services

3.3.1. Access to Culture

“I do see a clinical counsellor every couple of weeks but I don’t see that as being more helpful than going to the beading group, than going to Métis Night at the Friendship Centre”.[25] (p. 95)

3.3.2. Traditional Healing

Doctors today don’t know who we are, especially when we are using walk-in clinics. Our traditional doctors knew us, they knew our family, and they talked to our ancestors in ceremony. If we got sick, our parents knew where to go, and not just to one person, there were different people in the community.[36] (p. e395)

3.3.3. Indigenous-Led and Run Health Services

I went to another downtown clinic and the doctor that I had was giving me constantly the same pills all the time when I was getting sick. I went over to the Native Health and the doctor there, as soon as she saw me, said, ‘Get to the hospital.’ And now she is my doctor. She is somebody who cares and takes the time to listen to me.[51] (p. 826)

3.3.4. Access to Culturally Safe Care

I think that I have to mention cultural safety. It’s so important. It’s something that should be a way of being for everyone, so that we can develop respectful relationships with no matter who it is. […] If I know where our people are, like the Ki-Low-Na Friendship Society, I’d rather go there.[39] (p. e827)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canadian Geographic. Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. 2020. Available online: https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/section/truth-and-reconciliation/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Key Results from the 2016 Census. 2017. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Dickason, O.P.; Newbigging, W. A Concise History of Canada’s First Nations. 2015. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/concise-history-of-canadas-first-nations/oclc/895341415 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples. Relocation of Aboriginal Communities. In Report on the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples; Indian and Northern Affairs: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1991; Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100014597/1572547985018 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. Understanding the Needs of Urban Inuit Women. 2017. Available online: https://pauktuutit.ca/project/understanding-the-needs-of-urban-inuit-women-final-report/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Patrick, D.; Tomiak, J.A.; Brown, L.; Langille, H.; Vieru, M. Regaining the Childhood I Should Have Had: The Transformation of the Inuit. In Aboriginal Peoples in Canadian Cities: Transformation and Continuities; Howard, H., Proulx, C., Eds.; Wilfred Laurier University Press: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. National Report of the First Nations Regional Health Survey Phase 3: Volume One. 2018. Available online: https://niagaraknowledgeexchange.com/resources-publications/first-nations-regional-health-survey-phase-3-volume-1-2/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- O’Brien, X.; Wolfe, S.; Maddox, R.; Laliberte, N.; Smylie, J. Adult Access to Health Care—Our Health Counts Toronto. 2018. Available online: http://www.welllivinghouse.com/what-we-do/projects/our-health-counts/our-health-counts-toronto/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/subjects/standard/pc (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Harrison, H.; Griffin, S.J.; Kuhn, I.; Usher-Smith, J.A. Software Tools to Support Title and Abstract Screening for Systematic Reviews in Healthcare: An Evaluation. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Wilson, K. Microsoft Excel 2013. In Using Office 365; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboriginal Health Access Centres. Bringing Order to Indigenous Primary Health Care Planning and Delivery in Ontario. 2016. Available online: https://iportal.usask.ca/record/59345 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Aboriginal Health Access Centres; Aboriginal Community Health Centres. Our Health, Our Seventh Generation, Our Future. 2015. Available online: https://soahac.on.ca/our-health-our-seventh-generation-our-future-2015-aboriginal-health-access-centres-report/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Carter, A.; Greene, S.; Nicholson, V.; Dahlby, J.; Pokomandy, A.; Loutfy, M.R. “You Know Exactly Where You Stand in Line. Its Right at the Very Bottom of the List”: Negotiating Place and Space among Women Living with HIV Seeking Health Care in British Columbia, Canada. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 25 (Suppl. SA), 25A–26A. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, J.; Varcoe, C.; Browne, A.J. Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Accessing Health Care When State Apprehension of Children Is Being Threatened. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environics Institute. Urban Aboriginal Peoples Study. 2010. Available online: https://www.uaps.ca/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Firestone, M.; Smylie, J.; Maracle, S.; McKnight, C.; Spiller, M.; O’Campo, P. Mental Health and Substance Use in an Urban First Nations Population in Hamilton, Ontario. Can. J. Public Health 2015, 106, e375–e381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.; Smylie, J.; Maracle, S.; Spiller, M.; O’Campo, P. Unmasking Health Determinants and Health Outcomes for Urban First Nations Using Respondent-Driven Sampling. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Fleming, K.; Markwick, N.; Morrison, T.; Lagimodiere, L.; Kerr, T. “They Treated Me like Crap and I Know It Was Because I Was Native”: The Healthcare Experiences of Aboriginal Peoples Living in Vancouver’s Inner City. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Snyder, M.; Wilson, K.; Whitford, J. Healthy Spaces: Exploring Urban Indigenous Youth Perspectives of Social Support and Health Using Photovoice. Health Place 2019, 56, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Council of Canada. Compendium of Promising Practices: Understanding and Improving Aboriginal Maternal and Child Health in Canada. 2003. Available online: https://childcarecanada.org/documents/research-policy-practice/11/08/understanding-and-improving-aboriginal-maternal-and-child (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Health Council of Canada. Canada’s Most Vulnerable: Improving Health Care for First Nations, Inuit, and Metis Seniors. 2013. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/458307/publication.html (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Health Council of Canada. Empathy, Dignity, and Respect: Creating Cultural Safety for Aboriginal People in Urban Health Care. 2012. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.698021/publication.html (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Auger, M.D. “We Need to not Be Footnotes Anymore”: Understanding Metis People’s Experiences with Mental Health and Wellness in British Columbia, Canada. Public Health 2019, 176, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaman, M. Evaluation of the Partners in Inner-City Integrated Prenatal Care (PIIPC) Project in Winnipeg, Canada: Perspectives of Women and Health Care Providers. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54 (Suppl. 1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaman, M.I.; Sword, W.; Elliott, L.; Moffatt, M.; Helewa, M.E.; Morris, H.; Gregory, P.; Tjaden, L. Barriers and Facilitators Related to Use of Prenatal Care by Inner-City Women: Perceptions of Health Care Providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, R.D.; Evans, M.; Berg, L.D.; Bottorff, J.L.; Dingwall, C.; Alexis, C.; Nyberg, J.; Smith, M.L. Visibility and Voice: Aboriginal People Experience Culturally Safe and Unsafe Health Care. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1662–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitching, G.T.; Firestone, M.; Schei, B.; Wolfe, S.; Bourgeois, C.; O’Campo, P.; Rotondi, M.; Nisenbaum, R.; Maddox, R.; Smylie, J. Unmet Health Needs and Discrimination by Healthcare Providers among an Indigenous Population in Toronto, Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, H.P.; Cidro, J.; Isaac-Mann, S.; Peressini, S.; Maar, M.; Schroth, R.J.; Gordon, J.N.; Hoffman-Goetz, L.; Broughton, J.R.; Jamieson, L. Racism and Oral Health Outcomes among Pregnant Canadian Aboriginal Women. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27 (Suppl. 1), 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyola-Sanchez, A.; Hazlewood, G.; Crowshoe, L.; Linkert, T.; Hull, P.M.; Marshall, D.; Barnabe, C. Qualitative Study of Treatment Preferences for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Pharmacotherapy Acceptance: Indigenous Patient Perspectives. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaskill, D.; FitzMaurice, K.; Cidro, J. Toronto Abgoriginal Research Project. 2011. Available online: https://tarp.indigenousto.ca/about-toronto-aboriginal-research-project-tarp/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Mill, J.E.; Jackson, R.C.; Worthington, C.A.; Archibald, C.P.; Wong, T.; Myers, T.; Prentice, T.; Sommerfeldt, S. HIV Testing and Care in Canadian Aboriginal Youth: A Community Based Mixed Methods Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, S.E.; Wilson, K. Understanding Barriers to Health Care Access through Cultural Safety and Ethical Space: Indigenous People’s Experiences in Prince George, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 218, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowgesic, E.; Meili, R.; Stack, S.; Myers, T. The Indigenous Red Ribbon Storytelling Study: What Does It Mean for Indigenous Peoples Living with HIV and a Substance Use Disorder to Access Antiretroviral Therapy in Saskatchewan? Can. J. Aborig. Commu.-Based HIV/AIDS Res. 2015, 7, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, M.; Howell, T.; Gomes, T. Moving toward Holistic Wellness, Empowerment and Self-Determination for Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Can Traditional Indigenous Health Care Practices Increase Ownership over Health and Health Care Decisions? Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e393–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Xavier, C.; Kitching, G.; Maddox, R.; Muise, G.M.; Dokis, B.; Smylie, J. Adult Access to Health Care Findings, Access to Health Care Findings & Community Priorities. Our Health Counts London. 2016. Available online: https://soahac.on.ca/our-health-counts/#:~:text=Our%20Health%20Counts%20is%20a,Well%20Living%20House%20at%20St (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Pearce, M.E.; Jongbloed, K.; Demerais, L.; MacDonald, H.; Christian, W.M.; Sharma, R.; Pick, N.; Yoshida, E.M.; Spittal, P.M.; Klein, M.B. “Another Thing to Live for”: Supporting HCV Treatment and Cure among Indigenous People Impacted by Substance Use in Canadian Cities. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 74, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, K.; Terbasket, E.; Thurston, W.E.; Kurtz, D.; Page, S.; McLean, F.; Jim, R.; Oelke, N. Everything Is Related and It All Leads Up to My Mental Well-Being: A Qualitative Study of the Determinants of Mental Wellness Amongst Urban Indigenous Elders. Br. J. Soc. Work 2019, 49, 860–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smye, V.; Browne, A.J.; Varcoe, C.; Josewski, V. Harm Reduction, Methadone Maintenance Treatment and the Root Causes of Health and Social Inequities: An Intersectional Lens in the Canadian Context. Harm Reduct. J. 2011, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smylie, J.; Firestone, M.; Cochran, L.; Prince, C.; Maracle, S.; Morley, M.; Mayo, S.; Spiller, T.; McPherson, B. Our Health Counts Hamilton. 2011. Available online: http://www.welllivinghouse.com/what-we-do/projects/our-health-counts/our-health-counts-hamilton/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Tang, S.Y.; Browne, A.J.; Mussell, B.; Smye, V.L.; Rodney, P. “Underclassism” and Access to Healthcare in Urban Centres. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tungasuvvingat Inuit. Our Health Counts—Urban Indigenous Health Database Project—Inuit Adults Living in Ottawa. 2017. Available online: https://tiontario.ca/resources (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Van Herk, K.A.; Smith, D.; Tedford Gold, S. Safe Care Spaces and Places: Exploring Urban Aboriginal Families’ Access to Preventive Care. Health Place 2012, 18, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well Living House. Discrimination Factsheet, Our Health Counts Toronto. 2016. Available online: http://www.welllivinghouse.com/what-we-do/projects/our-health-counts/our-health-counts-toronto/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Barnabe, C.; Lockerbie, S.; Erasmus, E.; Crowshoe, L. Facilitated Access to an Integrated Model of Care for Arthritis in an Urban Aboriginal Population. Can. Fam. Physician 2017, 63, 699–706. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.L.; Jack, S.M.; Ballantyne, M.; Gabel, C.; Bomberry, R.; Wahoush, O. Indigenous Mothers’ Experiences of Using Primary Care in Hamilton, Ontario, for Their Infants. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2019, 14, 1600940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, L.; McConkey, S. Insiders’ Insight: Discrimination against Indigenous Peoples through the Eyes of Health Care Professionals. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, M.; Firestone, M.A.; McKnight, C.D.; Smylie, J.; Rotondi, M.A. A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Relationship between Diabetes and Health Access Barriers in an Urban First Nations Population in Canada. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, A.C.; Cotnam, J.; O’Brien-Teengs, D.; Greene, S.; Beaver, K.; Zoccole, A.; Loutfy, M. Racism Experiences of Urban Indigenous Women in Ontario, Canada: “We All Have That Story That Will Break Your Heart”. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2019, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, C.; Carroll, D.; Chaudhry, M. In Search of a Healing Place: Aboriginal Women in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J.; Smye, V.L.; Rodney, P.; Tang, S.Y.; Mussell, B.; O’Neil, J. Access to Primary Care from the Perspective of Aboriginal Patients at an Urban Emergency Department. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, B.L.; Carmargo Plazas, M.D.P.; Salas, A.S.; Bourque Bearskin, R.L.; Hungler, K. Understanding Inequalities in Access to Health Care Services for Aboriginal People: A Callfor Nursing Action. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2014, 37, E1–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsden, I. Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. 2002. Available online: https://www.nccih.ca/634/cultural_safety_and_nursing_education_in_aotearoa_and_te_waipounamu.nccih?id=1124 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yaphe, S.; Richer, F.; Martin, C. Cultural Safety Training for Health Professionals Working with Indigenous Populations in Montreal, Quebec. Int. J. Indig. Health 2019, 14, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, D. Having the Hard Conversations: Strengthening Pedagogical Effectiveness by Working with Student and Institutional Resistance to Indigenous Health Curriculum. 2020. Available online: https://limenetwork.net.au/resources-hub/resource-database/having-the-hard-conversations-strengthening-pedagogical-effectiveness-by-working-with-student-and-institutional-resistance-to-indigenous-health-curriculum-final-report/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/110ef308-c848-4537-b0e7-6d8c53589194/aihw-aus-221-chapter-6-2.pdf.aspx (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Kelaher, M.A.; Ferdinand, A.S.; Paradies, Y. Experiencing Racism in Health Care: The Mental Health Impacts for Victorian Aboriginal Communities. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 201, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, A.J. Clinical Encounters between Nurses and First Nations Women in a Western Canadian Hospital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J. Discourses Influencing Nurses’ Perceptions of First Nations Patients. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 41, 166–191. [Google Scholar]

- Lokugamage, A.U.; Rix, E.; Fleming, T.; Khetan, T.; Meredith, A.; Hastie, C.R. Translating Cultural Safety to the UK. J. Med. Ethics 2021, 49, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P.; Lloyd, J.E.; Joshi, C.; Malera-Bandjalan, K.; Baldry, E.; McEntyre, E.; Sherwood, J.; Reath, J.; Indig, D.; Harris, M.F. Do Programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Leaving Prison Meet Their Health and Social Support Needs? Aust. J. Rural Health 2018, 26, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormel, H.; Kok, M.; Kane, S.; Ahmed, R.; Chikaphupha, K.; Rashid, S.F.; Gemechu, D.; Otiso, L.; Sidat, M.; Theobald, S.; et al. Salaried and Voluntary Community Health Workers: Exploring How Incentives and Expectation Gaps Influence Motivation. Jum Resour Health 2019, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, G.; Khakpour, M.; Carr, T.; Groot, G. Exploring Indigenous Traditional Healing Programs in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand: A Scoping Review. Explore 2023, 19, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, M.A.; O’Campo, P.; O’Brien, K.; Firestone, M.; Wolfe, S.H.; Bourgeois, C.; Smylie, J.K. Our Health Counts Toronto: Using Respondent-Driven Sampling to Unmask Census Undercounts of an Urban Indigenous Population in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year Published | Location | Indigenous Group A | Participants | Sample Size | Study Design, Methods | Health Service Focus B | Incentives Provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal Health Access Centres, 2015 [14] | Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | 50,000 | Quantitative | Primary health services | Not Stated |

| Aboriginal Health Access Centres, 2016 [13] | Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | 50,000 | Quantitative | Primary health services | Not stated |

| Auger et al., 2016 [36] | Vancouver, British Columbia | First Nations (status), First Nations (non-status), Métis | Family members or carers of Indigenous people with type 2 diabetes | 35 | Qualitative | Diabetic patients | $35 gift card |

| Auger, 2019 [25] | Vancouver, British Columbia | Métis | 23 women and 10 men accessing mental health services | 33 | Qualitative | Mental health | $25 gift card |

| Barnabe et al., 2017 [46] | Calgary, Alberta | First Nations | Adults | 38 | Quantitative | Primary health services at the Elbow River Health Lodge | None provided |

| Beckett et al., 2018 [49] | Hamilton, Ontario | First Nations | Adults | 524 | Quantitative | Diabetic patients | $20 plus $10 for each person they recruit |

| Benoit et al., 2003 [51] | Vancouver, British Columbia | First Nations | Adult women | 61 | Qualitative | Primary health services at the Vancouver Native Health Society (VNHS) and Sheway | An honorarium was provided |

| Benoit et al., 2019 [50] | Toronto and Thunder Bay, Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Women living with and without HIV | 90 | Mixed methods | Multiple | Not stated |

| Browne et al., 2011 [52] | Vancouver, British Columbia | First Nations, Métis, non-status Indigenous people | Patients of the emergency department (ED) and ED staff. 44 patients, 38 staff. | 82 | Quantitative | Emergency department of a hospital | None provided |

| Cameron et al., 2014 [53] | Edmonton, Alberta | First Nations, Métis | Aboriginal patients in hospital and their families | 19 | Qualitative | Emergency department of a hospital | Not stated |

| Carter et al., 2014 [15] | Vancouver, Victoria, Prince George, British Columbia | First Nations | Women living with HIV | 28 | Qualitative | HIV testing and treatment services and hospitals | Not stated |

| Denison et al., 2014 [16] | Northern British Columbia | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Mothers where apprehension of their children is being threatened | 9 | Qualitative | Hospital | Not stated |

| Environics Institute, 2010 [17] | Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Regina, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Montreal, Toronto, Halifax and Ottawa | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | 2614 | Qualitative | Multiple | Not stated |

| Firestone et al., 2014 [19] | Hamilton, Ontario | First Nations | Adults | 554 | Quantitative | Primary health care services | $20 to participate plus $10 for each person they recruited |

| Firestone et al., 2015 [18] | Hamilton, Ontario | First Nations | Adults | 554 | Quantitative | Mental health | $20 to participate plus $10 for each person they recruited |

| Goodman et al., 2017 [20] | Vancouver, British Columbia | First Nations | Adults | 30 | Qualitative | Drug, alcohol and substance use services | Not stated |

| Goodman et al., 2019 [21] | Winnipeg, Manitoba | First Nations | Young people (15–25 years) | 8 | Qualitative | Primary health services | None provided |

| Health Council of Canada, 2003 [22] | Multiple provinces | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Pregnant women and mothers | Not reported | Qualitative | Maternal, post natal and child health | Not reported |

| Health Council of Canada, 2012 [24] | Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, and St. John’s | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | 160 | Qualitative | Primary health services | Not reported |

| Health Council of Canada, 2013 [23] | Vancouver, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Iqaluit, Inuvik, and Happy Valley-Goose Bay | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Elders | Not reported | Qualitative | Primary health services | Not reported |

| Heaman et al., 2015 [27] | Winnipeg, Manitoba | First nations | Pregnant women | 26 | Qualitative | Maternal and prenatal care | $20 grocery gift card |

| Heaman, 2018 [26] | Winnipeg, Manitoba | First nations | 24 postpartum women, 30 healthcare providers | 24 | Qualitative | Maternal and prenatal care | $20 grocery gift card |

| Hole et al., 2015 [28] | Kelowna, British Columbia | First Nations | Adults | 28 | Qualitative | Hospital | Not stated |

| Kitching et al., 2020 [29] | Toronto, Ontario | First Nations | Adults | 836 | Quantitative | Primary health service | $20 to participate plus $10 for each person they recruited |

| Lawrence et al., 2016 [30] | Ontario, Manitoba | First Nations, Métis | Pregnant women | 541 | Quantitative | Dental services | Not stated |

| Loyola-Sanchez et al., 2020 [31] | Southern Alberta | Indigenous | Patients needing Arthritis services | 13 | Qualitative | Rheumatology arthritis practices | Not stated |

| McCaskill et al., 2011 [32] | Toronto, Ontario | First Nations | Adults | 1059 (623 surveys and 436 interviews) | Mixed methods | Multiple | $5 gift card |

| Mill et al., 2008 [33] | Vancouver, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, Halifax, Labrador, Inuvik | Aboriginal | Youth (15–30 years) | 441 (413 surveys and 28 interviews) | Mixed methods | HIV testing and management | Participants were provided with a small token of appreciation (no further info provided). Participating organizations received a small compensation for staff time. |

| Nelson et al., 2018 [34] | Prince George, British Columbia | First Nations | Adults | 50 | Qualitative | Primary health care service | Not stated |

| Nowgesic et al., 2015 [35] | Saskatoon and Prince Albert, Saskatchewan | First Nations | Adults | 20 | Qualitative | HIV treatment and management | Cash $20 per hour, travel expenses $20, childcare expenses $40, a small tobacco bundle, an Indigenous gift |

| O’Brien et al., 2016 [37] | London, Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | Not stated | Quantitative | Any type | $20 to participate plus $10 for each person they recruited |

| Pearce et al., 2019 [38] | Vancouver, Prince George, Sudbury, Regina, Saskatchewan | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | People who use illicit drugs and are accessing hepatitis C treatment | 45 | Qualitative | Hepatitis C clinics | Cash |

| Schill et al., 2019 [39] | Kelowna, British Columbia | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Elders | 9 | Qualitative | Mental health | $25 for each sharing circle the elders attended |

| Smylie et al., 2011 [41] | Hamilton, Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults and children | 790 | Quantitative | Any type | $10 |

| Syme et al., 2011 [40] | Vancouver, British Columbia | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | 60 | Qualitative | Mental health and addictions services | $30 each |

| Tang et al., 2015 [42] | Vancouver, British Columbia | Indigenous | Adults | 34 | Qualitative | Emergency department of a hospital | Not stated |

| Tungasuvvingat Inuit, 2017 [43] | Ottawa, Ontario | Inuit | Adults | 345 | Quantitative | Any type | $10 to participate plus $10 for each person they recruited |

| Van Herk et al., 2012 [44] | Ottawa, Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | 26 | Qualitative | Services for women, social services for all | Not stated |

| Well Living House, 2016 [45] | Toronto, Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Adults | Not stated | Quantitative | Any type | $20 to participate plus $10 for each person they recruited |

| Wright et al., 2019 [47] | Hamilton, Ontario | First Nations, Métis | Pregnant women | 19 | Qualitative | Primary health services | Not stated |

| Wylie et al., 2019 [48] | Urban city in southern Ontario | First Nations, Inuit, Métis | Health care providers | 25 | Qualitative | Primary health services | Not stated |

| Author, Year | Barriers to Accessing Health Care | Facilitators to Accessing Health Care |

|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal Health Access Centres, 2015 [14] |

|

|

| Aboriginal Health Access Centres, 2016 [13] |

|

|

| Auger et al., 2016 [36] |

|

|

| Auger, 2019 [25] |

|

|

| Barnabe et al., 2017 [46] |

|

|

| Beckett et al., 2018 [49] |

|

|

| Benoit et al., 2003 [51] |

|

|

| Benoit et al., 2019 [50] |

|

|

| Browne et al., 2011 [52] |

|

|

| Cameron et al., 2014 [53] |

|

|

| Carter et al., 2014 [15] |

|

|

| Denison et al., 2014 [16] |

|

|

| Environics Institute, 2010 [17] |

|

|

| Firestone et al., 2014 [19] |

|

|

| Firestone et al., 2015 [18] |

|

|

| Goodman et al., 2017 [20] |

|

|

| Goodman et al., 2019 [21] |

|

|

| Health Council of Canada, 2003 [22] |

|

|

| Health Council of Canada, 2012 [24] |

|

|

| Health Council of Canada, 2013 [23] |

|

|

| Heaman et al., 2015 [27] |

|

|

| Heaman, 2018 [26] |

|

|

| Hole et al., 2015 [28] |

|

|

| Kitching et al., 2020 [29] |

|

|

| Lawrence et al., 2016 [30] |

|

|

| Loyola-Sanchez et al., 2020 [31] |

|

|

| McCaskill et al., 2011 [32] |

|

|

| Mill et al., 2008 [33] |

|

|

| Nelson et al., 2018 [34] |

|

|

| Nowgesic et al., 2015 [35] |

|

|

| O’Brien et al., 2016 [37] |

|

|

| Pearce et al., 2019 [38] |

|

|

| Schill et al., 2019 [39] |

|

|

| Smylie et al., 2011 [41] |

|

|

| Syme et al., 2011 [40] |

|

|

| Tang et al., 2015 [42] |

|

|

| Tungasuvvingat Inuit, 2017 [43] |

|

|

| Van Herk et al., 2012 [44] |

|

|

| Well Living House, 2016 [45] |

|

|

| Wright et al., 2019 [47] |

|

|

| Wylie et al., 2019 [48] |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graham, S.; Muir, N.M.; Formsma, J.W.; Smylie, J. First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples Living in Urban Areas of Canada and Their Access to Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115956

Graham S, Muir NM, Formsma JW, Smylie J. First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples Living in Urban Areas of Canada and Their Access to Healthcare: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115956

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraham, Simon, Nicole M. Muir, Jocelyn W. Formsma, and Janet Smylie. 2023. "First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples Living in Urban Areas of Canada and Their Access to Healthcare: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115956

APA StyleGraham, S., Muir, N. M., Formsma, J. W., & Smylie, J. (2023). First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples Living in Urban Areas of Canada and Their Access to Healthcare: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115956