The Representation of Children’s Participation in Guidelines for Planning and Designing Public Playspaces: A Scoping Review with “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

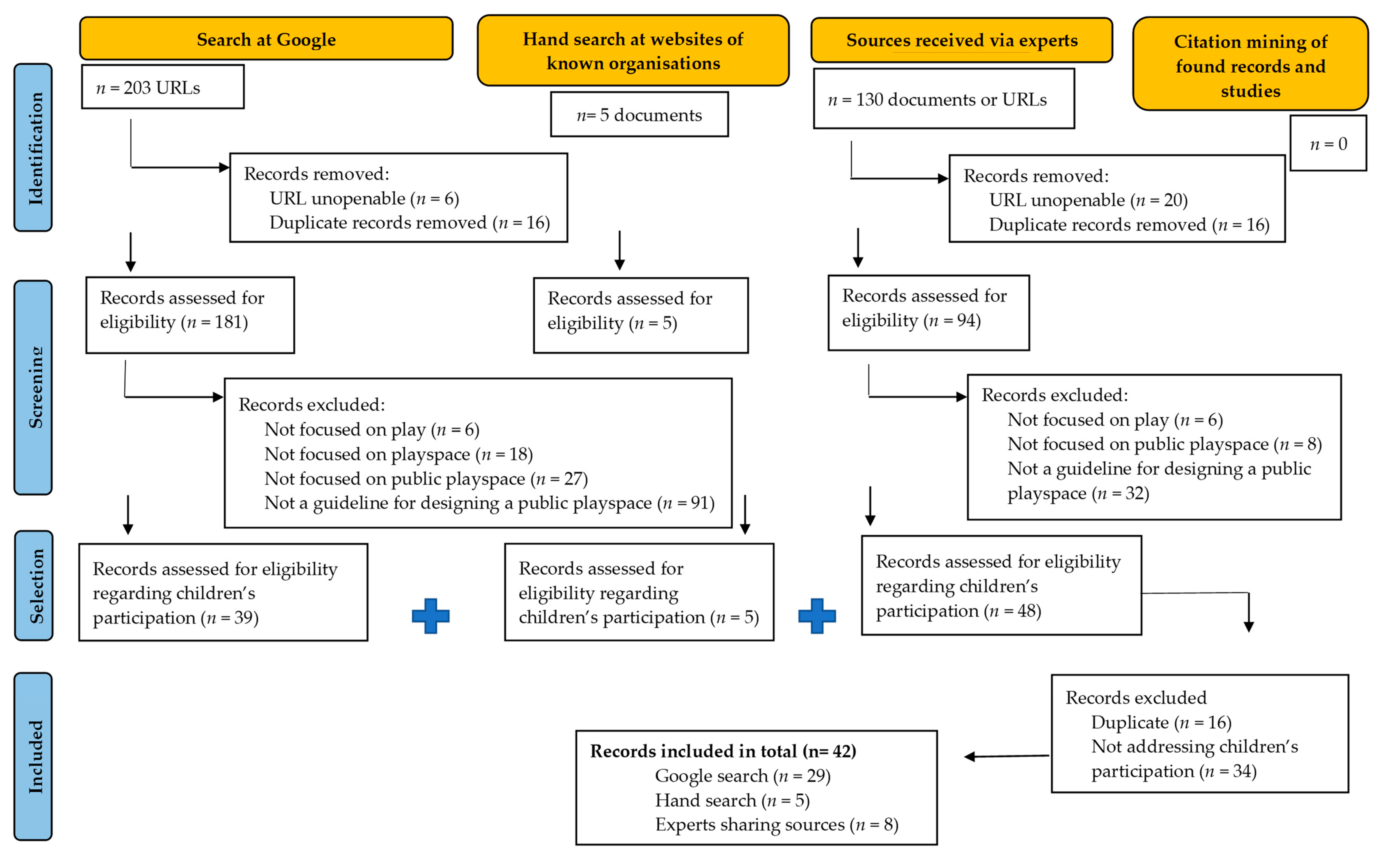

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Eligibility

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Critical Appraisal of Included Sources

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Guidelines on Designing Public Playspaces

3.2. Modes for Participation

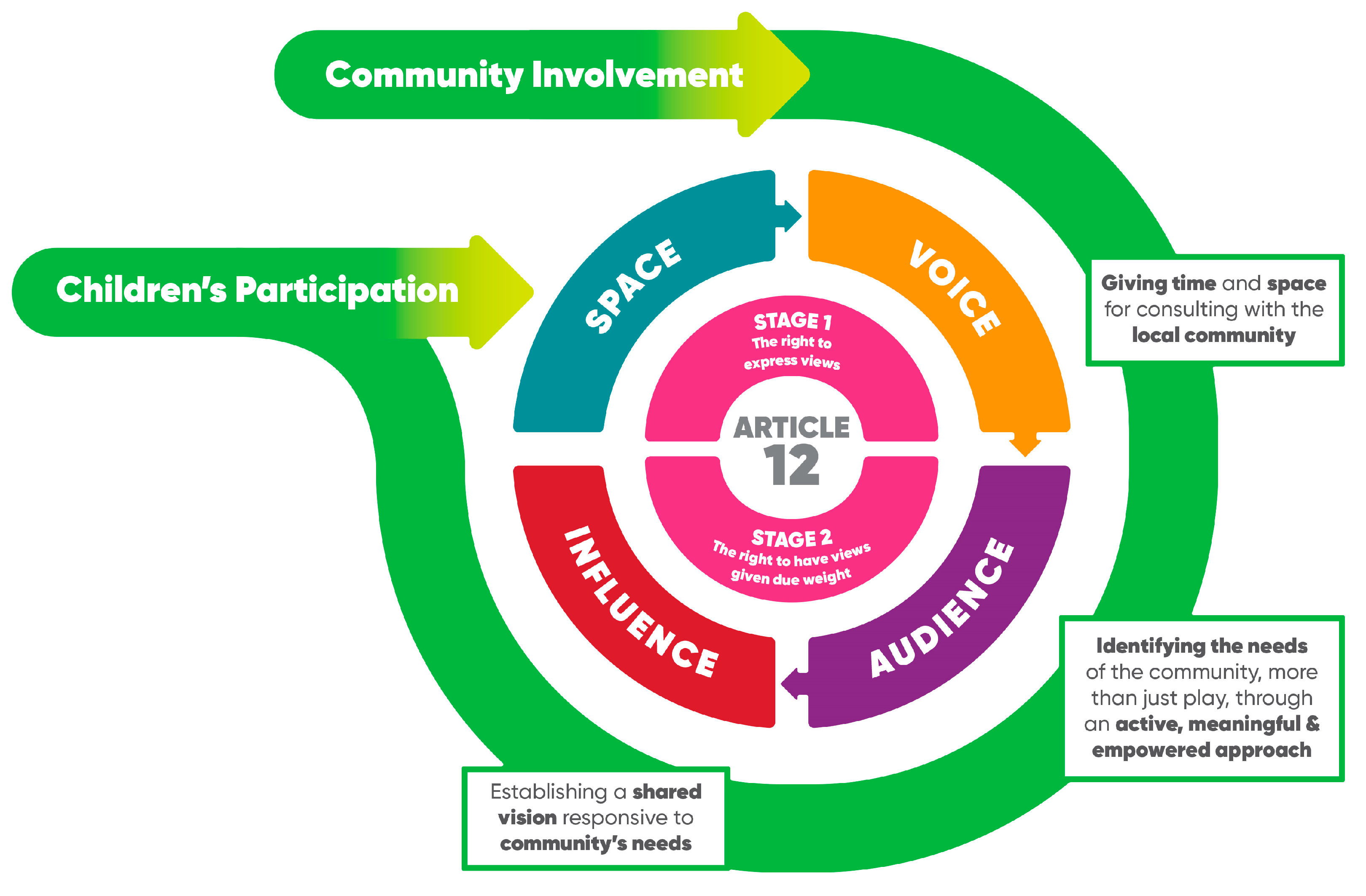

3.3. “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis: Themes on Children’s Participation and Community Involvement

3.3.1. Theme 1: Giving Space and Time for Consulting with the Local Community

3.3.2. Theme 2: Identifying the Needs of the Community, beyond Play, through an Active, Meaningful and Empowered Approach

3.3.3. Theme 3: Establishing a Shared Vision Responsive to Community’s Needs

3.3.4. Theme 4: Giving Children Safe, Inclusive Opportunities to Form and Express Their Views about Playspaces

3.3.5. Theme 5: Facilitating Children to Express Their Views

3.3.6. Theme 6: Informing Children Who Will Be Listening to Their Views on Playspaces

3.3.7. Theme 7: Informing Children of Actions Taken as a Result of Their Shared Views

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lester, S. Everyday playfulness. In A New Approach to Children’s Play and Adults Responses to It; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prellwitz, M.; Lynch, H. Universal design for social inclusion: Playgrounds for all. In Seen and Heard: Exploring Participation, Engagement and Voice for Children with Disabilities.; Twomey, M., Carroll, C., Eds.; Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, M.A.; Devan, H.; Fitzgerald, H.; Han, K.; Liu, L.T.; Rouse, J. Accessibility and usability of parks and playgrounds. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Lynch, H.; Boyle, B. Can universal design support outdoor play, social participation, and inclusion in public playgrounds? A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 44, 3304–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, H.; Jansens, R.; Prellwitz, M. Having a say in places to play-children with disabilities, voice, participation. In The Routledge Handbook of the Built Environments of Diverse Childhoods; Bishop, K., Dimoulias, K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis/Routledge Informa Ltd: New York, NY, USA, submitted.

- General Comment no. 17 on the Right of the Child to Rest, Leisure, Play, Recreational Activities, Cultural Life and the Arts (Art. 31). 2013. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9bcc4.html (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Lester, S.; Russell, W. Children’s Right to Play: An Examination of the Importance of Play in the Lives of Children Worldwide. Working Paper no. 57; Bernard van Leer Foundation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2010; Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/3819.pdf/ (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Derr, V.; Tarantini, E. “Because we are all people”: Outcomes and reflections from young people’s participation in the planning and design of child-friendly public spaces. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 1534–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M. Children’s perspectives on playground use as basis for children’s participation in local play space management. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeppich, A.; Koller, D.; McLaren, C. Children’s Right to Participate in Playground Development: A Critical Review. Child. Youth Environ. 2021, 31, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Herbert, E.; Zalar, A.; Johansson, M. Child-Friendly Environments—What, How and by Whom? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prellwitz, M.; Skär, L. Usability of playgrounds for children with different abilities. Occup. Ther. Int. 2007, 14, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandwania, D.; Natu, A. Study of perception of parents and their children about day-to-day outdoor play spaces. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 192, 2280–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansdown, G. Article 12: The right to be heard. In Monitoring State Compliance with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. An Analysis of Attributes; Vaghri, Z., Zermatten, J., Lansdown, G., Ruggiero, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jansens, R.; Lynch, H.; Olofsson, A.; Prellwitz, M. Connecting children’s right to participation to play policies: Reviewing if and how this right is represented in guidelines for designing public playspaces. In Proceedings of the Child in the City World Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 5–7 October 2022; p. 45. Available online: https://www.childinthecity.org/2022-conference/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Child-in-the-City-2022_Dublin_book-of-abstracts_UPDATED.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Lundy, L. “Voice” is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansdown, G. Conceptual Framework for Measuring Outcomes of Adolescent Participation; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.unicef.cn/media/17311/file/Participation%20in%20Practice.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Byrne, B.; Lundy, L. Reconciling children’s policy and children’s rights: Barriers to effective government delivery. Child. Soc. 2015, 29, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, C.; Lundy, L. Towards greater recognition of the right to play: An analysis of article 31 of the UNCRC. Child. Soc. 2011, 25, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Lynch, H.; Boyle, B. A national study of playground professionals universal design implementation practices. Landsc. Res. 2022, 47, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionary. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/ (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Daudt, H.M.L.; van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement 2021, 191, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahood, Q.; van Eerd, D.; Irvin, E. Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansens, R.; Lynch, H.; Olofssen, A.; Prellwitz, M. The Representation of Children’s Participation in Guidelines for Designing a Public Playspace: Protocol for a Scoping Review and “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. 2022. Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/6524757#.ZF4yUBHMI2w (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Lewin, S.; Langlois, E.V.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Portela, A. Assessing unConventional Evidence (ACE) tool: Development and content of a tool to assess the strengths and limitations of “unconventional” source materials. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2023, Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, C.; Booth, A.; Cooper, K. A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Booth, A.; Leaviss, J.; Rick, J. “Best fit” framework synthesis: Refining the method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Participation Framework. National Framework for Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making. 2021. Available online: https://hubnanog.ie/participation-framework/ (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- NVivo. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Shier, H.; Méndez, M.H.; Centeno, M.; Arróliga, I.; González, M. How children and young people influence policy-makers: Lessons from Nicaragua. Child. Soc. 2014, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corney, T.; Cooper, T.; Shier, H.; Williamson, H. Youth participation: Adultism, human rights and professional youth work. Child. Soc. 2021, 36, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, H.; Kennan, D. Child and Youth Participation in Policy, Practice and Research; Routledge: Oxon, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M.; Lorenzo, R. Seven realms of children’s participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, D.; Forde, C.; Martin, S.; Parkes, A. Children’s participation: Moving from the performative to the social. Child. Geogr. 2017, 15, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkoway, B. What is youth participation? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Ramberg, U. Implementation and effects of user participation in playground management: A comparative study of two Swedish municipalities. Manag. Leis. 2012, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsikali, A.; Parnell, R.; McIntyre, L. The public value of child-friendly space: Reconceptualising the playground. Archnet-IJAR 2020, 14, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.S.; Mistry, R.S. Parent Civic Beliefs, Civic Participation, Socialization Practices, and Child Civic Engagement. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2016, 20, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizek, K.; Forysth, A.; Slotterback, C.S. Is there a role for evidence-based practice in urban planning and policy? Plan. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Characteristics of Children’s Rights. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/what-are-human-rights (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Sterman, J.J.; Naughton, G.A.; Bundy, A.C.; Froude, E.; Villeneuve, M.A. Planning for outdoor play: Government and family decision-making. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 26, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, R.G.; Batagol, B.; Raven, R. “Critical Agents of Change?”: Opportunities and Limits to Children’s Participation in Urban Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2021, 36, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iltus, S.; Hart, R. Participatory planning and design of recreational spaces with children. Arch. Comport. Arch. Behav. 1995, 10, 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, L. Journeys to play: Planning considerations to engender inclusive playspaces. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Affiliated Institution or Organization | Type of Organization | Year of Publication | Country | Title and Subtitle | Type of Document According to Authors | Objective of the Guideline According to Authors | Intended Audience According to Authors | Modus of Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Australian Heart Foundation | Non-governmental organization (NGO) | 2013 | Australia | Space for active play. Developing child-inspired play space for older children | Guideline | To assist local governments in undertaking “healthy urban planning” | Local governments | Consultation |

| 2 | CABE | Cooperation of diverse stakeholders | 2008 | United Kingdom | Designing and planning for play | Briefing | To highlight best practice in design and strategies and encourage the greater use of creative and natural playspaces | Local planners, developers and architects | Consultation |

| 3 | Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation | NGO | n.d. | USA | Toolkit for building an inclusive community playground | Toolkit | To provide community advocates with resources and tips to broaden their understanding of the requirements of inclusive playgrounds and provide suggestions to facilitate fundraising efforts | Community advocates | Collaboration |

| 4 | City of Ballarat | Government agency | 2014 | Australia | City of Ballarat play space planning framework | Planning framework | To provide a planning framework to improve and develop playspaces | Citizens, professionals and others involved in the processes | Collaboration |

| 5 | Creo | Playground building industry | n.d. | New Zealand | We create smart public play spaces | Not described | Not described | Clients | Too little information |

| 6 | Denver Parks and Recreation | Government agency | 2017 | USA–Canada | Nature play design guidelines | Guideline | To provide a framework for parks and recreation, urban drainage, forestry and public works. To establish unstructured sensory play, align the nature play design process and develop a maintenance and facilities process | Public servants, funders, health and wellness advocates, communities and children | Collaboration |

| 7 | DESSA | Government agency | 2007 | Ireland | Play for all. Providing play facilities for disabled children | Publication | To support community development projects, family resource centers and other community development organizations in ensuring their play facilities are accessible and welcoming to all children | Community development organizations, planners, architects, local authority staff and interested individuals | Consultation |

| 8 | Free Play Network | NGO network | 2008 | United Kingdom | Design for play: A guide to creating successful play spaces | Presentation | To support the creation of successful playspaces | Not described | Consultation |

| 9 | Geelong Australia | Government agency | 2012 | Australia | Geelong play strategy: Part 2. Planning and design guidelines, management, marketing and maintenance of play space | Report | To provide a good overview of playground development considerations | The community of the Greater City of Geelong | Collaboration |

| 10 | Government South Australia | Government agency | n.d. | Australia | Inclusive play guidelines for accessible play spaces (easy read version) | Guideline | To provide an easy read guideline | Anyone planning or building new playgrounds or playspaces | Consultation |

| 11 | Greater London Authority | Government agency | 2012 | UK | Shaping neighborhoods: play and informal recreation. Supplementary planning guidance | Planning guidance | To support how planning should be carried out, with practical advice, in particular by negotiating for enough playspace to be set aside in new developments | Not described | Consultation |

| 12 | Hags | Playground building industry | 2019 | Worldwide | Inclusive play design guide | Guide | To contribute to more inclusive spaces for everyone | Individuals and groups aiming to create playspaces in their communities | Collaboration |

| 13 | HNH (Healthy New Hampshire) Foundation and NRPC (Nashua Regional Planning Commission) | NGO | 2017 | USA | Planning for play. A parks and playground guidebook for New Hampshire | Guidebook | To understand the process of park and playground development, from planning to implementation | Local authorities in New Hampshire, USA | Consultation |

| 14 | Illinois Department of Natural Resources | Government agency | 2004 | USA | A guide to playground planning | Guide | To provide information and assistance in the planning, design, installation and maintenance of public playgrounds | Local governmental agencies with minimal or no permanent staff, as well as community groups with limited knowledge or experience in developing public playgrounds | Consultation |

| 15 | Inclusive SA (South Australia) | Government agency | n.d. | Australia | Guidelines for accessible play spaces | Guideline | To challenge standard practice and inspire innovative design solutions that ensure playspaces can be enjoyed by every South Australian | Local governments, schools, early childhood learning centers, design professionals and others | Consultation |

| 16 | Inspiring Scotland, Play Scotland and the Nancy Ovens Trust | NGO network | 2018 | Scotland, UK | Free to play guide to accessible and inclusive play spaces | Guide | To assist any group that come together to develop or improve public playspaces | Friends of parks, community councils, community planning partnerships and groups of local parents, carers, professionals and youngsters | Consultation |

| 17 | Landcom | Government agency | 2008 | Australia | Open space design guideline | Guidelines | To help to deliver the best outcomes for open spaces | The two principal partners and the end owner (usually this means local councils and Landcom development staff) | Collaboration |

| 18 | Landscape Structures Inc. | Playground building industry | 2018 | USA | Inclusive play space design planning guide | Guide | To help to create inclusive playgrounds that are unique to their communities | Not described | Collaboration |

| 19 | National Playing Fields Association | NGO | 2004 | UK | Can play, will play. Disabled children and access to outdoor playgrounds | Report | To advise local authorities and other playground managers and assist them in meeting the requirements of the Disability Discrimination Act | Local authorities and other playground managers | Collaboration |

| 20 | NCB (National Children’s Bureau) | NGO | 2009 | UK | How to involve children and young people in designing and developing play spaces | guide | To be used alongside the Design for Play: A guide to creating | All those involved in designing and developing playspaces for children and young people | Collaboration |

| 21 | NSW (New South Wales) Government | Government agency | 2019 | Australia | Everyone can play guideline. A guideline to create inclusive play spaces | Guideline | To provide a key resource for the planning, design and evaluation of new and existing playspaces in NSW (New South Wales, Australia) | Councils, community leaders, landscape architects and local residents | Consultation |

| 22 | Office of Deputy Prime Minister | Government agency | 2003 | UK | Developing Accessible Play Space. A Good Practice Guide | Guide | To advise on developing accessible playspaces that disabled children can use | All stakeholders | Collaboration |

| 23 | Play England, Department for Children, Schools and Families, Department for Culture, Media and Sport | NGO | 2008 | England, UK | Design for Play. A guide to creating successful place spaces | Guide (non-statutory guidance) | To support good practice in the development and improvement of public playspaces | Commissioners, designers, playbuilders, and local authorities | Consultation |

| 24 | Play Wales | NGO | 2012 | Wales, UK | Play spaces—planning and design | Not described | Not described | Not described | Consultation |

| 25 | Play Wales | NGO | 2016 | Wales, UK | Community toolkit. Developing and managing play spaces | Toolkit | To provide a single source of support and signposting for community groups to help them to navigate some of the challenges of managing or developing playspaces | Anyone taking responsibility for managing or developing playspaces in communities | Collaboration |

| 26 | Play Wales | NGO | 2021 | Wales, UK | Developing and managing play spaces. Community toolkit | Toolkit (providing guidance and tools) | To provide a single source of support and signposting to navigate some of the challenges of managing or developing playspaces | Anyone taking responsibility for managing or developing playspaces in communities, e.g., community councils, local play associations or resident groups | Collaboration |

| 27 | Playcore | Playground building industry | 2012 | USA | Blueprint for Play Design It. | Toolkit | To inspire communities to maximize the play design process for community-based initiatives | Not described | Determine the level of involvement |

| 28 | Playground Ideas | NGO | n.d. | Australia–Thailand | 5 steps for a better place to play | Manual | To empower people to go out and create amazing playspaces with their communities | Not described | Collaboration |

| 29 | Playright | NGO | 2016 | Hong Kong | Inclusive Play Space Guide | Guide | To advise and inspire the design of accessible and inclusive playspaces in Hong Kong | Designers, play providers and operators of unsupervised playspaces in Hong Kong | Collaboration |

| 30 | Playworld | Playground building industry | 2015 | USA | Inclusive Play Design Guide | Guide | To guide the creation of great outdoor play environments for everyone | People who care about inclusion and aim to create playspaces in their communities | Collaboration |

| 31 | Playworld Systems | Playground building industry | 2015 | USA | Playground 101 Guide. How to build a playground in 10 easy steps | Guide | To help answer questions, as well as provide educational resources | Not described | Collaboration |

| 32 | Playworld Systems | Playground building industry | 2019 | USA | Inclusive Play Design Guide | Guide | To offer inspiration and guidance to support the design of inclusive and universally designed outdoor playgrounds | Landscape architects, park and recreation staff, municipal employees, parent/teacher groups, community groups, parents and educators | Collaboration |

| 33 | Real Play Coalition | Cooperation of diverse stakeholders | 2020 | Worldwide | Reclaiming Play in Cities. The Real Play Coalition Approach | Publication | To share the initial steps toward developing an urban play framework (a holistic tool for facilitating play) | City stakeholders, including decision-makers, urban practitioners and investors | Too little information |

| 34 | Rick Hansen Foundation | NGO | n.d. | Canada | Let’s play toolkit. Creating inclusive play spaces for children of all abilities | Toolkit | To provide information and best practices for designing accessible playspaces for all children | Communities | Consultation |

| 35 | Rick Hansen Foundation | NGO | 2020 | Canada | A guide to creating accessible play spaces | Guide/toolkit | To support the design of accessible and inclusive playspaces | Communities | Consultation |

| 36 | State of Victoria, Dept for Victorian Communities | Government agency | 2007 | Australia | The good play space guide: “I can play too” | Guide | To examine the reasons why playspaces can limit access to some children and identify how improvements can be made to increase participation by all children in play | The providers of public playspaces | Collaboration |

| 37 | Touched by Olivia | NGO | n.d. | Australia | The principles for inclusive play | Principles | Not described | Not described | Collaboration |

| 38 | Tualatin Hills Park and Recreation District | Government agency | 2012 | USA | Nature play area guidelines | Guidelines/document | To support the design and implementation of nature play areas | Tualatin Hills Park and Recreation District staff and contractors | Too little information |

| 39 | Unknown | Government agency | 2014 | Canada | Integrated accessibility standards regulation guidelines. Part 4.1: Design of public spaces standard | Guideline/standard | To inform about the regulations for outdoor spaces | Organizations interested in constructing or redeveloping outdoor spaces | Consultation |

| 40 | Waverley Council | Government agency | 2021 | Australia | Inclusive play space study report Abridged version | Report/study | To provide practical guidance on inclusive playspace design and help to translate best practice policy into actionable principles | Inclusive play specialists, landscape architects and other interested parties | Collaboration |

| 41 | Wexford County Council Community Development Department | Government agency | 2018 | Ireland | Developing a play area in your community. A step-by-step guide | Guide/booklet | To help to develop play areas for children in communities | Communities | Consultation |

| 42 | Wokingham Borough Council | Government agency | 2018 | UK | Play space design guide | Guide | To provide clients, developers and designers with guidance and specific requirements for the design of playspaces within the borough | Planning officers | Too little information |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jansens, R.; Prellwitz, M.; Olofsson, A.; Lynch, H. The Representation of Children’s Participation in Guidelines for Planning and Designing Public Playspaces: A Scoping Review with “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105823

Jansens R, Prellwitz M, Olofsson A, Lynch H. The Representation of Children’s Participation in Guidelines for Planning and Designing Public Playspaces: A Scoping Review with “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105823

Chicago/Turabian StyleJansens, Rianne, Maria Prellwitz, Alexandra Olofsson, and Helen Lynch. 2023. "The Representation of Children’s Participation in Guidelines for Planning and Designing Public Playspaces: A Scoping Review with “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105823

APA StyleJansens, R., Prellwitz, M., Olofsson, A., & Lynch, H. (2023). The Representation of Children’s Participation in Guidelines for Planning and Designing Public Playspaces: A Scoping Review with “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105823