Retrospective Real-Life Data, Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib Treatment in Patients with Advanced and Multiple Basal Cell Carcinoma: 3-Year Experience from a Spanish Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Efficacy

3.3. Adverse Events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nisticò, S.P.; Bennardo, L.; Sannino, M.; Negosanti, F.; Tamburi, F.; del Duca, E.; Giudice, A.; Cannarozzo, G. Combined CO2 and Dye Laser Technique in the Treatment of Outcomes Due to Flap Necrosis after Surgery for Basal Cell Carcinoma on the Nose. Lasers Surg. Med. 2022, 54, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, S.R.; Brianti, P.; Dattola, A.; Bennardo, L.; Silvestri, M.; Schipani, G.; Nisticò, S.P. CO2 Laser and Photodynamic Therapy: Study of Efficacy in Periocular BCC. Dermatol. Ther. 2018, 31, e12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciążyńska, M.; Kamińska-Winciorek, G.; Lange, D.; Lewandowski, B.; Reich, A.; Sławińska, M.; Pabianek, M.; Szczepaniak, K.; Hankiewicz, A.; Ułańska, M.; et al. The Incidence and Clinical Analysis of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, M.C.; Lee, E.; Hibler, B.P.; Barker, C.A.; Mori, S.; Cordova, M.; Nehal, K.S.; Rossi, A.M. Basal Cell Carcinoma: Epidemiology; Pathophysiology; Clinical and Histological Subtypes; and Disease Associations. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, P.; Kłosińska, M.; Forma, A.; Pelc, Z.; Gęca, K.; Skórzewska, M. Novel Approaches in Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers-A Focus on Hedgehog Pathway in Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC). Cells 2022, 11, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris, K.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Garbe, C.; Kaufmann, R.; Bastholt, L.; Seguin, N.B.; Bataille, V.; Del Marmol, V.; Dummer, R.; Harwood, C.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: European Consensus-Based Interdisciplinary Guidelines. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 118, 10–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, G.; Karagiannis, T.; Palmer, J.B.; Lotya, J.; O’Neill, C.; Kisa, R.; Herrera, V.; Siegel, D.M. Incidence and Prevalence of Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) and Locally Advanced BCC (LABCC) in a Large Commercially Insured Population in the United States: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 957–966.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Ruiz, E.S. Current Perspectives in the Treatment of Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Drug. Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, 16, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apalla, Z.; Spyridis, I.; Kyrgidis, A.; Lazaridou, E.; Kyriakou, A.; Fotiadou, C.; Pikou, O.; Sotiriou, E.; Vakirlis, E.; Papageorgiou, C.; et al. Vismodegib in Real-Life Clinical Settings: A Multicenter, Longitudinal Cohort Providing Long-Term Data on Efficacy and Safety. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fecher, L.A. Systemic Therapy for Inoperable and Metastatic Basal Cell Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2013, 14, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basset-Séguin, N.; Hauschild, A.; Kunstfeld, R.; Grob, J.; Dréno, B.; Mortier, L.; Ascierto, P.A.; Licitra, L.; Dutriaux, C.; Thomas, L.; et al. Vismodegib in Patients with Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: Primary Analysis of STEVIE, an International, Open-Label Trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 86, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lear, J.T.; Dummer, R.; Guminski, A. Using Drug Scheduling to Manage Adverse Events Associated with Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors for Basal Cell Carcinoma. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walling, H.W.; Fosko, S.W.; Geraminejad, P.A.; Whitaker, D.C.; Arpey, C.J. Aggressive Basal Cell Carcinoma: Presentation, Pathogenesis, and Management. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004, 23, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, P. Current Landscape for Treatment of Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2015, 56, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likhacheva, A.; Awan, M.; Barker, C.A.; Bhatnagar, A.; Bradfield, L.; Brady, M.S.; Buzurovic, I.; Geiger, J.L.; Parvathaneni, U.; Zaky, S.; et al. Definitive and Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Basal and Squamous Cell Cancers of the Skin: Executive Summary of an American Society for Radiation Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 10, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niebel, D.; Sirokay, J.; Hoffmann, F.; Fröhlich, A.; Bieber, T.; Landsberg, J. Clinical Management of Locally Advanced Basal-Cell Carcinomas and Future Therapeutic Directions. Dermatol. Ther. (Heidelb.) 2020, 10, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelson, M.; Liu, K.; Jiang, X.; He, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Kufrin, D.; Palmby, T.; Dong, Z.; Russell, A.M.; et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Approval: Vismodegib for Recurrent, Locally Advanced, or Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 2289–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, A.; Migden, M.R.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Garbe, C.; Gesierich, A.; Lao, C.D.; Miller, C.; Mortier, L.; Murrell, D.F.; Hamid, O.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Vismodegib in Patients with Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: Final Update of the Pivotal ERIVANCE BCC Study. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreno, B.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Caro, I.; Yue, H.; Schadendorf, D. Clinical Benefit Assessment of Vismodegib Therapy in Patients With Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Oncologist 2014, 19, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernia, E.; Llombart, B.; Serra-Guillén, C.; Bancalari, B.; Nagore, E.; Requena, C.; Calomarde, L.; Diago, A.; Lavernia, J.; Traves, V.; et al. Experience with Vismodegib in the Treatment of Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma at a Cancer Center. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018, 109, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bánvölgyi, A.; Anker, P.; Lőrincz, K.; Kiss, N.; Márton, D.; Fésűs, L.; Gyöngyösi, N.; Wikonkál, N. Smoothened Receptor Inhibitor Vismodegib for the Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Analysis of Efficacy and Side Effects. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 31, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, A.; Yoo, S.; Kudchadkar, R.; Guillen, J.; Rogers, G.; Chang, A.L.S.; Guenthner, S.; Raskin, B.; Dawson, K.; Mun, Y.; et al. Real-World Assessment and Treatment of Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: Findings from the RegiSONIC Disease Registry. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, J.P.; Samlowski, W.; Meoz, R. Hedgehog Inhibitor Induction with Addition of Concurrent Superficial Radiotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Series. Oncologist 2021, 26, e2247–e2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, N.; Guerreschi, P.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Saiag, P.; Dupuy, A.; Dalac-Rat, S.; Dziwniel, V.; Depoortère, C.; Duhamel, A.; Mortier, L. Vismodegib in Neoadjuvant Treatment of Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: First Results of a Multicenter, Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial (VISMONEO Study): Neoadjuvant Vismodegib in Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 35, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.D.; Ravichandran, S.; Kheterpal, M. Hedgehog Inhibitors with and without Adjunctive Therapy in Treatment of Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juzot, C.; Isvy-Joubert, A.; Khammari, A.; Knol, A.C.; Nguyen, J.M.; Dreno, B. Predictive Factors of Response to Vismodegib: A French Study of 61 Patients with Multiple or Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2022, 32, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herms, F.; Lambert, J.; Grob, J.J.; Haudebourg, L.; Bagot, M.; Dalac, S.; Dutriaux, C.; Guillot, B.; Jeudy, G.; Mateus, C.; et al. Follow-Up of Patients With Complete Remission of Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma After Vismodegib Discontinuation: A Multicenter French Study of 116 Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3275–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargnoli, M.C.; Pellegrini, C.; Piccerillo, A.; Spallone, G.; Rocco, T.; Ventura, A.; Necozione, S.; Bianchi, L.; Peris, K.; Cortellini, A. Clinical Determinants of Complete Response to Vismodegib in Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Multicentre Experience. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e923–e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Goldberg, L.H.; Silapunt, S.; Gardner, E.S.; Strom, S.S.; Rademaker, A.W.; Margolis, D.J. Delayed Treatment and Continued Growth of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 64, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplash, G.; Curragh, D.S.; Halliday, L.; Huilgol, S.C.; Selva, D. Report of Cutaneous Side Effects of Vismodegib Treatment. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 48, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, A.; Migden, M.R.; Oro, A.E.; Dirix, L.; Lewis, K.D.; Hainsworth, J.D.; Solomon, J.A.; Yoo, S.; Arron, S.T.; Friedlander, P.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib in Advanced Basal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dréno, B.; Kunstfeld, R.; Hauschild, A.; Fosko, S.; Zloty, D.; Labeille, B.; Grob, J.J.; Puig, S.; Gilberg, F.; Bergström, D.; et al. Two Intermittent Vismodegib Dosing Regimens in Patients with Multiple Basal-Cell Carcinomas (MIKIE): A Randomised, Regimen-Controlled, Double-Blind, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Moigne, M.; Saint-Jean, M.; Jirka, A.; Quéreux, G.; Peuvrel, L.; Brocard, A.; Gaultier, A.; Khammari, A.; Darmaun, D.; Dréno, B. Dysgeusia and Weight Loss under Treatment with Vismodegib: Benefit of Nutritional Management. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 1689–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spallone, G.; Sollena, P.; Ventura, A.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Gutierrez, C.; Piccerillo, A.; Tambone, S.; Bianchi, L.; Peris, K. Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib Treatment in Patients with Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma and Multiple Comorbidities. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e13108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heppt, M.V.; Gebhardt, C.; Hassel, J.C.; Alter, M.; Gutzmer, R.; Leiter, U.; Berking, C. Long-Term Management of Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Costa, C.; Fabbrocini, G.; Cappello, M.; Scalvenzi, M. Reply to: “Comparison of Daily Dosing vs. Monday through Friday Dosing of Vismodegib for Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma (LaBCC) and Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome: A Retrospective Case Series.”. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, e201–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Sex | Comorbidities | Subtype BCC | Tumor Location | Tumor Size (cm) | Self-Reported Presence of BCC (Years) | Previous Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63 | F | HT | Multiple nodular | Abdomen Neck Arm | 8 × 8 5 × 4 6 × 6 | 10 | N |

| 2 | 86 | F | HT, DLP, complete AV block, arthrosis | Nodular and sclerosing | Left inner canthus eye | 2 × 2 | 2 | Surgery (relapse) |

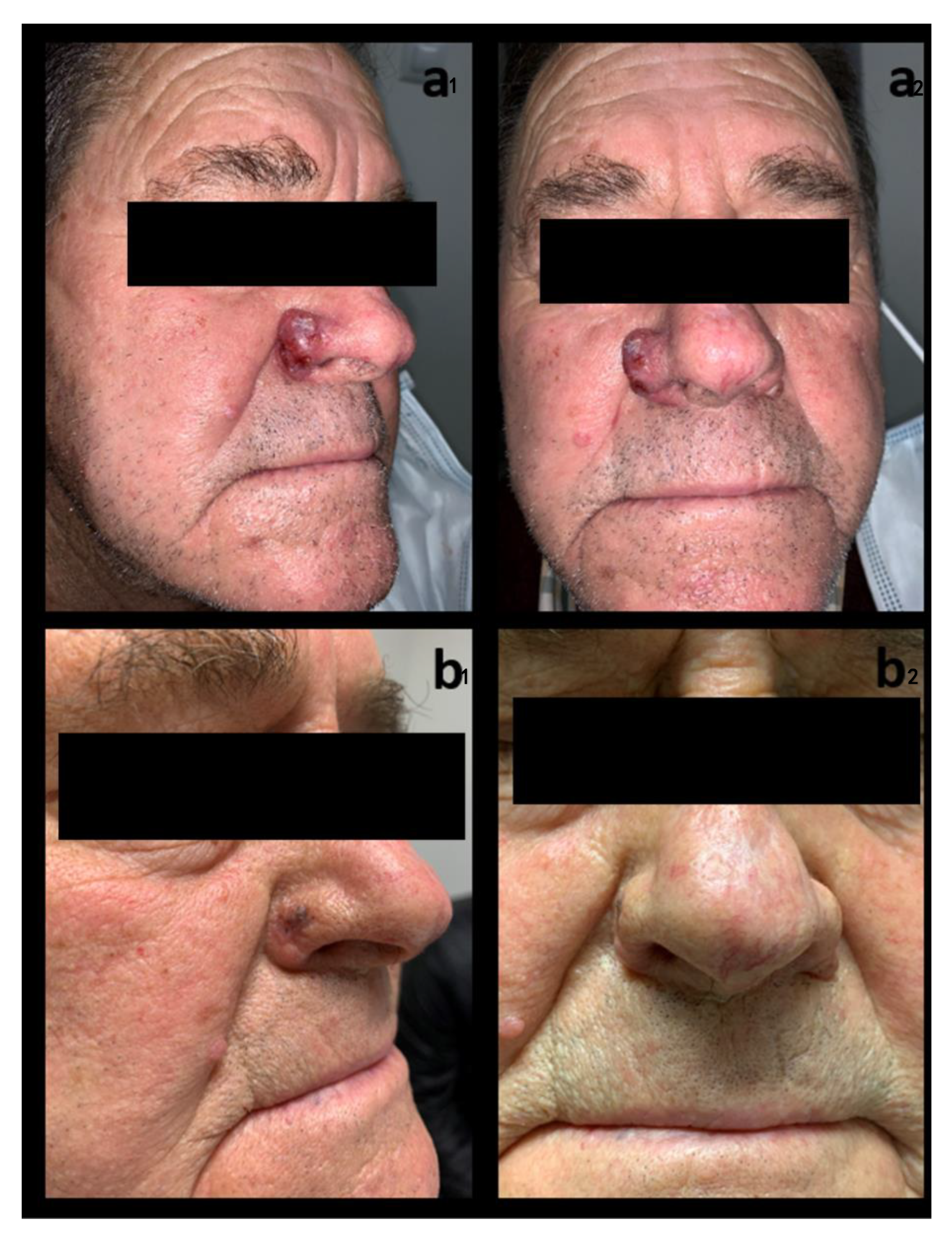

| 3 | 71 | M | T2DM, DLP | Nodular | Right nasal wing | 2 × 2 | 1 | N |

| 4 | 90 | F | DLP, vascular dementia, DLBCL of the parotid gland, CHD, RA | Nodular and sclerosing | Glabella and right inner canthus eye | 3.5 × 4 | 3 | N |

| 5 | 85 | M | HT, T2DM, DLP, CHD | Infiltrative and sclerosing | Wings and nasal dorsum | 5 × 4 | 11 | Surgery (with positive margins) |

| 6 | 76 | M | - | Nodular | Right supraciliary and palpebral | 6.2 × 2 | 2 | N |

| Id | Daily Dosage | Time of Treatment (Months) | Clinical Response | Histological Confirmation of Response | Time to Initial/Best Response (Months) | Subsequent Treatment | Follow-Up Post-Treatment | Relapse | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150 mg | 6 | CR | Y | 1/6 | Follow-up | 26 | N | Alopecia, muscle spasms |

| 2 | 150 mg–150 mg/48 h | 6 | CR | Y | 1/4 | Follow-up | 25 | N | Asthenia, muscle spasms |

| 3 | 150 mg | 2 | CR | Y | 1/2 | Mohs surgery | 20 | N | Muscle spasms, dysgeusia |

| 4 | 150 mg–150 mg/48 h | 5 | PR | N | 1/5 | - | - | - | Asthenia, dysgeusia, ↑CK |

| 5 | 150 mg | 6 | CR | Y | 2/3 | Follow-up | 11 | N | N |

| 6 | 150 mg | 6 | CR | Y | 1/3 | Follow-up | 7 | N | Alopecia, muscle spasms |

| Present Study (n = 6) | Stevie (n = 1215) | Erivance (n = 104) | Mikie | Different Rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 114) | Group B (n = 113) | |||||

| Any | 5 (83.3) | 1192 (98.1) | 104 (100.0) | 107 (93.9) | 109 (96.5) | −16.7 to −10.6 |

| Muscle spasm | 4 (66.7) | 807 (66.4) | 74 (71.2) | 83 (72.8) | 93 (82.3) | −15.6 to +0.3 |

| Alopecia | 2 (33.3) | 747 (61.5) | 69 (66.3) | 72 (63.2) | 73 (64.6) | −30.0 to −28.2 |

| Dysgeusia | 2 (33.3) | 663 (54.6) | 58 (55.8) | 75 (65.8) | 75 (66.4) | −33.1 to −21.3 |

| Decreased weight | 0 | 493 (40.6) | 54 (51.9) | 24 (21.1) | 21 (18.6) | |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 303 (24.9) | 29 (27.9) | 21 (18.4) | 17 (15.0) | |

| Asthenia | 2 (33.3) | 291 (24.0) | 0 | 15 (13.2) | 20 (17.7) | +9.3 to +20.1 |

| Nausea | 0 | 218 (17.9) | 34 (32.7) | 23 (20.2) | 15 (13.3) | |

| Ageusia | 0 | 213 (17.5) | 12 (11.5) | 14 (12.3) | 13 (11.5) | |

| Fatigue | 0 | 201 (16.5) | 45 (43.3) | 24 (21.1) | 26 (23.0) | |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 197 (16.2) | 28 (26.9) | 20 (17.6) | 18 (15.9) | |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 124 (10.2) | 17 (16.3) | 18 (15.8) | 16 (14.2) | |

| Constipation | 0 | 116 (9.5) | 20 (19.2) | 0 | 0 | |

| Vomiting | 0 | 102 (8.4) | 18 (17.3) | 0 | 0 | |

| Headache | 0 | 92 (7.6) | 15 (14.4) | 11 (10) | 11 (4) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayén-Rodríguez, A.; Linares-González, L.; Llamas-Segura, C.; Almazán-Fernández, F.M.; Ruiz-Villaverde, R. Retrospective Real-Life Data, Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib Treatment in Patients with Advanced and Multiple Basal Cell Carcinoma: 3-Year Experience from a Spanish Center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105824

Ayén-Rodríguez A, Linares-González L, Llamas-Segura C, Almazán-Fernández FM, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Retrospective Real-Life Data, Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib Treatment in Patients with Advanced and Multiple Basal Cell Carcinoma: 3-Year Experience from a Spanish Center. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105824

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyén-Rodríguez, Angela, Laura Linares-González, Carlos Llamas-Segura, Francisco Manuel Almazán-Fernández, and Ricardo Ruiz-Villaverde. 2023. "Retrospective Real-Life Data, Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib Treatment in Patients with Advanced and Multiple Basal Cell Carcinoma: 3-Year Experience from a Spanish Center" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105824

APA StyleAyén-Rodríguez, A., Linares-González, L., Llamas-Segura, C., Almazán-Fernández, F. M., & Ruiz-Villaverde, R. (2023). Retrospective Real-Life Data, Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib Treatment in Patients with Advanced and Multiple Basal Cell Carcinoma: 3-Year Experience from a Spanish Center. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105824