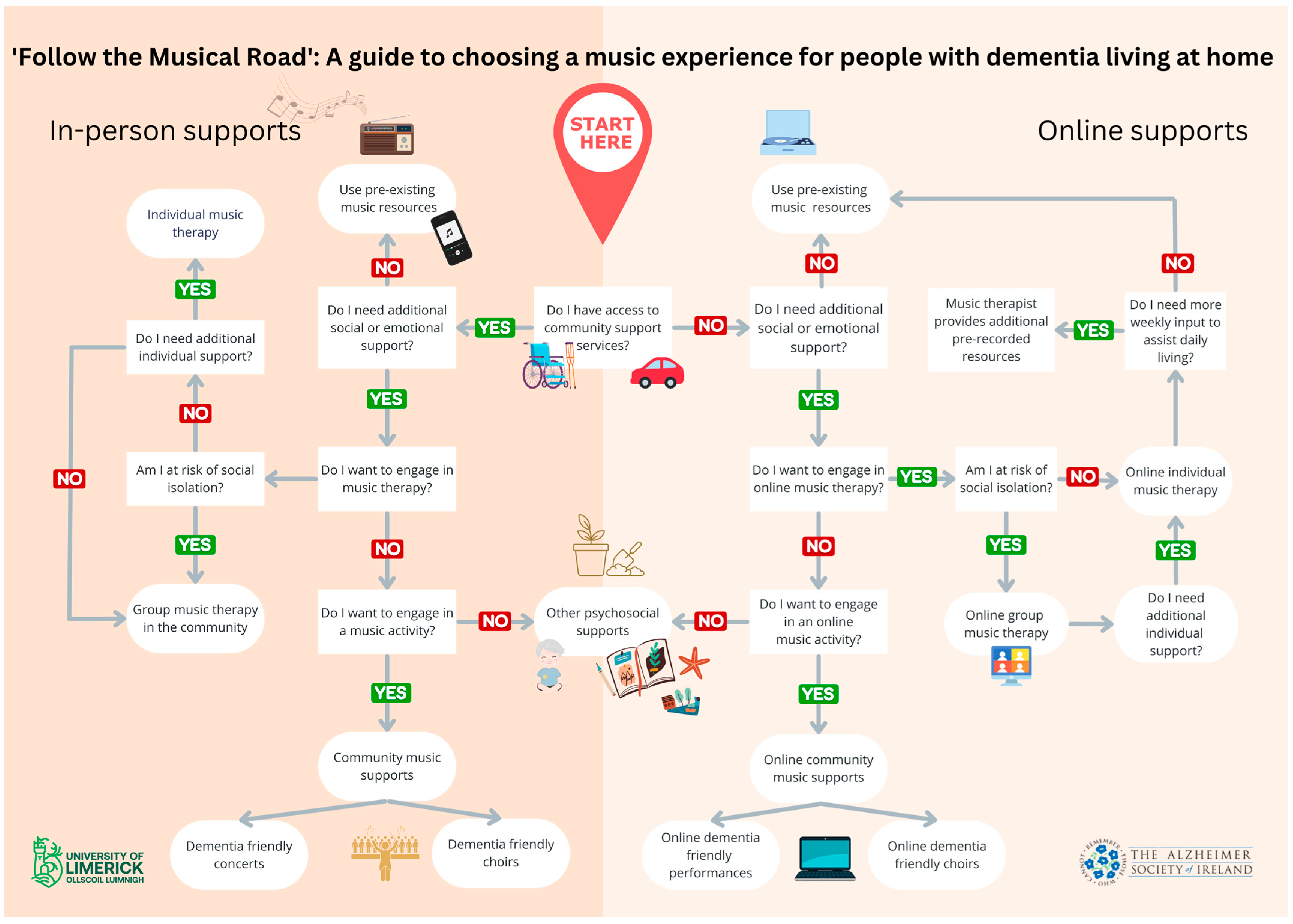

“Follow the Musical Road”: Selecting Appropriate Music Experiences for People with Dementia Living in the Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Music in Dementia Care—A Continuum of Experiences

1.2. The Musical Care Pathway—A Useful Model

2. Literature Review

2.1. Music Listening

2.2. Dementia-Friendly Concerts

2.3. Continuing to Play/Learning to Play an Instrument

2.4. Group Singing and Dementia-Inclusive Choirs for People with Dementia and Their Caregivers

2.5. Music Therapy

3. Methods

3.1. Research Approach

3.2. Participants

3.3. Research Method

3.4. Ethics

3.5. Research Design

3.5.1. Phase One: Focus Group with PPI Participants

3.5.2. Phase Two: Semi-Structured Interviews with Music Therapists

- How do you see this document being used?

- Can you see this being utilized more by music therapists, other professionals or people living with dementia and their family caregivers?

- Do you think that there is anything that should be changed/added/removed?

- Is there anything that you think doesn’t make sense?

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1

- The identification of the various music experiences and supports for people with dementia.

- How does a person with dementia living at home and/or their family caregiver determine what music experience may suit them best?

- The need for a person-centered approach to be adopted when designing services for people with dementia.

- To provide psychosocial support services to people with dementia who are unable to access community support services in person via telehealth.

4.2. Phase Two

4.3. The Final Draft

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Draper, B. Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Camicioli, R. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of dementia. In Dementia; Quinn, J.F., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Dementia. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- O’Brien, J.T.; Thomas, A. Vascular dementia. Lancet 2015, 386, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.; Ballard, C.; Corbett, A.; Aarsland, D. The prognosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J.; Spina, S.; Miller, B.L. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet 2015, 386, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on the Public Health ‘Response to Dementia 2017–2025. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513487 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Department of Health. The Irish National Dementia Strategy; Department of Health: Dublin, Ireland, 2014; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10147/558608 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Dyer, S.M.; Harrison, S.L.; Laver, K.; Whitehead, C.; Crotty, M. An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carozza, L.; Serrone, L.M.; Sugatan, L. Non-pharmacological approaches to dementia: An overview of foundations & considerations. Music Med. 2017, 9, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019 (Health Evidence Network (HEN) Synthesis Report 67). Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329834/9789289054553-eng.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Clements-Cortés, A. Understanding the continuum of musical experiences for people living with dementia. In Music and Dementia: From Cognition to Therapy; Baird, A., Garrido, S., Tamplin, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Morales, C.; Calero, R.; Moreno-Morales, P.; Pintado, C. Music therapy in the treatment of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, T.; Suzukamo, Y.; Sato, M.; Izumi, S. Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, L.M.; Ross, S.D.; Rodriguez, F.S. Music-based interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia: A systematic review. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 2186–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Ahessy, B.; Richardson, I.; Moss, H. Aligning Kitwood’s model of person-centered dementia care with music therapy practice. Music Ther. Perpesct, 2023; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L.; Millett, E.; Richardson, I.; Moss, H. How do people with dementia and their caregivers use music and technology at home? Factors to be considered when designing a telehealth music therapy programme. Rural. Remote Health, 2023; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L.; Richardson, I.; Moss, H. Music therapists’ experiences of providing telehealth music therapy for people with dementia: A qualitative exploration. Voices A World Forum Music. Ther. 2023; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L.; Kenny, N.; McGlynn, C.; Richardson, I.; Moss, H. Exploring the Experiences of a Person with Dementia and Their Spouse Who Attended a Telehealth Music Therapy Programme: Two Case Examples; Irish World Academy of Music and Dance, University of Limerick: Limerick, Ireland, 2023; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Odell-Miller, H. Embedding music and music therapy in care pathways for people with dementia in the 21st Century—A position paper. Music Sci. 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, H. Music and creativity in healthcare settings: Does music matter? Routledge 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, H. Arts and health: A new paradigm. Voices A World Forum Music. Ther. 2016, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, S.; Dunne, L.; Chang, E.; Perz, J.; Stevens, C.J.; Haertsch, M. The use of music playlists for people with dementia: A critical synthesis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 60, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, R.A. Music, health, and well-being: A review. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being. 2013, 8, 20635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegemann, T.; Geretsegger, M.; Phan Quoc, E.; Riedl, H.; Smetana, M. Music therapy and other music-based interventions in pediatric health care: An overview. Medicines 2019, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannan, N.; Montgomery-Smith, C. ‘Singing for the brain’: Reflections on the human capacity for music arising from a pilot study of group singing with Alzheimer’s patients. R. Soc. Health J. 2008, 128, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowson, B.; McDermott, O.; Schneider, J. What indicators have been used to evaluate the impact of music on the health and wellbeing of people with dementia? A review using meta-narrative methods. Maturitas 2019, 127, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, S.E.; Tischler, V.; Schneider, J. ‘Singing for the Brain’: A qualitative study exploring the health and well-being benefits of singing for people with dementia and their carers. Dementia 2016, 15, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; O’Neill, D.; Moss, H. Promoting well-being among people with early-stage dementia and their family carers through community-based group singing: A phenomenological study. Arts Health 2022, 14, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; O’Neill, D.; Moss, H. Dementia-inclusive group-singing online during COVID-19: A qualitative exploration. Nord J Music Ther. 2022, 31, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bello-Haas, V.P.M.; O’Connell, M.E.; Morgan, D.G.; Crossley, M. Lessons learned: Feasibility and acceptability of a telehealth-delivered exercise intervention for rural dwelling individuals with dementia and their caregivers. Rural. Remote Health 2014, 14, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Cortés, A.; Mercadal-Brotons, M.; Alcântara Silva, T.R.; Vianna Moreira, S. Telehealth music therapy for persons with dementia and/or caregivers. Music Med. 2021, 13, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, C.; Hardy, T.; Lin, Y.-T.; McKinnon, K.; Odell-Miller, H. Together in Sound: Music therapy groups for people with dementia and their companions: Moving online in response to a pandemic. Approaches Interdiscip. J. Music. Ther. 2022, 14. Available online: https://approaches.gr/molyneux-r20201219/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Music for Dementia 2020. Musical Dementia Care Pathway. UK: The Utley Foundation. 2021. Available online: https://musicfordementia.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Musical-Dementia-Care-Pathway.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Laukka, P. Uses of music and psychological well-being among the elderly. J. Happiness. Stud. 2007, 8, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, T.; Minichiello, V. The contribution of music to quality of life in older people: An Australian qualitative study. Ageing Soc. 2005, 25, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, A.; Garrido, S.; Tamplin, J. Musical playlists for addressing depression in people with dementia. In Music and Dementia: From Cognition to Therapy; Baird, A., Garrido, S., Tamplin, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, S.; Stevens, C.J.; Chang, E.; Dunne, L.; Perz, J. Music and dementia: Individual differences in response to personalized playlists. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulibert, D.; Ebert, A.; Preman, S.; McFadden, S.H. In-home use of personalized music for persons with dementia. Dementia 2018, 18, 2971–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineweaver, T.T.; Bergeson, T.R.; Ladd, K.; Johnson, H.; Braid, D.; Ott, M.; Hay, D.P.; Plewes, J.; Hinds, M.; LaPradd, M.L.; et al. The effects of individualized music listening on affective, behavioral, cognitive, and sundowning symptoms of dementia in long-term care residents. J. Aging Health 2021, 34, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, L.; Töpfer, N.F.; Deux, J.; Wilz, G. Feasibility and effects of individualized recorded music for people with dementia: A pilot RCT study. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2020, 29, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.R.; Browne, W.; Marley, J.; Heim, C. Music and dementia. Degener. Neurol. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2013, 3, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, O.; Orrell, M.; Ridder, H.M.O. The importance of music for people with dementia: The perspectives of people with dementia, family carers, staff and music therapists. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibazaki, K.; Marshall, N.A. Exploring the impact of music concerts in promoting well-being in dementia care. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotons, M. An overview of the music therapy literature relating to elderly people. In Music Therapy in Dementia Care; Aldridge, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2000; pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Clair, A.A. The importance of singing with elderly patients. In Music Therapy in Dementia Care; Aldridge, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2000; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaino, C. The Role of Music in the Rehabilitation of Persons with Neurologic Diseases: Gaining Access to ‘Lost Memory’ and Preserved Function through Music Therapy. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242181393_The_Role_of_Music_in_the_Rehabilitation_of_Persons_with_Neurologic_Diseases_Gaining_Access_to_’Lost_Memory’_and_Preserved_Function_Through_Music_Therapy (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Dingle, G.A.; Sharman, L.S.; Bauer, Z.; Beckman, E.; Broughton, M.; Bunzli, E.; Davidson, R.; Draper, G.; Fairley, S.; Farrell, C.; et al. How do music activities affect health and well-being? A scoping review of studies examining psychosocial mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 713818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseldijk, L.W.; Ullén, F.; Mosing, M.A. The effects of playing music on mental health outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12606–12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, A.; Thompson, W.F. Preserved musical instrument playing in dementia: A unique form of access to memory and the self. In Music and Dementia: From Cognition to Therapy; Baird, A., Garrido, S., Tamplin, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Arafa, A.; Teramoto, M.; Maeda, S.; Sakai, Y.; Nosaka, S.; Gao, Q.; Kawachi, H.; Kashima, R.; Matsumoto, C.; Kokubo, Y. Playing a musical instrument and the risk of dementia among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.; Causer, R.; Brayne, C. Does playing a musical instrument reduce the incidence of cognitive impairment and dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansky, R.; Marzel, A.; Orav, E.J.; Chocano-Bedoya, P.O.; Grünheid, P.; Mattle, M.; Freystätter, G.; Stähelin, H.B.; Egli, A.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A. Playing a musical instrument is associated with slower cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, A.; Thompson, W.F. The impact of music on the self in dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 61, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahessy, B. The use of a music therapy choir to reduce depression and improve quality of life in older adults—A randomized control trial. Music Med. 2016, 8, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Särkämö, T. Music for the ageing brain: Cognitive, emotional, social, and neural benefits of musical leisure activities in stroke and dementia. Dementia 2018, 17, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.C.; Belza, B.; Nguyen, H.; Logsdon, R.; Demorest, S. Impact of group-singing on older adult health in senior living communities: A pilot study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 76, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.N.; Tamplin, J.; Baker, F.A. Community-dwelling people living with dementia and their family caregivers’ experiences of therapeutic group singing: A qualitative thematic analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements-Cortés, A. Clinical effects of choral singing for older adults. Music Med. 2015, 7, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamplin, J.; Clark, I.N.; Lee, Y.C.; Baker, F.A. Remini-Sing: A Feasibility Study of Therapeutic Group Singing to Support Relationship Quality and Wellbeing for Community-Dwelling People Living with Dementia and Their Family Caregivers. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Z.; Tamplin, J.; Clark, I.; Baker, F. Therapeutic choirs for families living with dementia: A phenomenological study. Act. Adapt. Aging 2022, 47, 40–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelman, M.S.; Papayannopoulou, P. M The Unforgettables: A chorus for people with dementia with their family members and friends. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B. Music therapy as a profession. In Music Therapy Handbook; Wheeler, B., Ed.; Guildford Press: New York, USA, 2015; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hanser, S.; Clements-Cortes, A.; Mercadal-Brotons, M.; Tomaino, C.M. Editorial: Music therapy in geriatrics. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.K. The effects of music therapy-singing group on quality of life and affect of persons with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J. Reconstructing the boundaries of dementia: Clinical improvisation as a musically mindful experience in long term care. Voices A World Forum Music. Ther. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlicevic, M.; Tsiris, G.; Wood, S.; Powell, H.; Graham, J.; Sanderson, R.; Millman, R.; Gibson, J. The ‘ripple effect’: Towards researching improvisational music therapy in dementia care homes. Dementia 2015, 14, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahessy, B. Song writing with clients who have dementia: A case study. Arts Psychother. 2017, 55, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Ahessy, B. Reminiscence-focused music therapy to promote positive mood and engagement and shared interaction for people living with dementia—An exploratory study. Voices A World Forum Music. Ther. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFerran, K.; Grocke, D. Receptive Music Therapy: Techniques, Clinical Applications and New Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, K.; McClune, N. Principles of person-centered care in music therapy. In Healing Arts Therapies and Person-Centered Dementia Care; Innes, A., Hatfield, K., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2002; pp. 79–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ridder, H.M.; Aldridge, D. Individual music therapy with persons with frontotemporal dementia. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2005, 14, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, F. Creative music therapy: Last resort? In Music Therapy in Dementia Care; Aldridge, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2000; pp. 166–183. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Burns, D.S.; Hilliard, R.E.; Stump, T.E.; Unroe, K.T. Music therapy clinical practice in hospice: Differences between home and nursing home delivery. J. Music Ther. 2015, 52, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative inquiry and research design, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, B.E.; Witkop, C.T.; Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghetti, C.M. Phenomenological research in music therapy. In The Oxford Handbook of Music Therapy; Edwards, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 767–800. [Google Scholar]

- INVOLVE. Briefing Notes for Researchers: Involving the Public in NHS, Public Health and Social Care Research; INVOLVE: Eastleigh, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/about-us/our-contribution-to-research/how-we-involve-patients-carers-and-the-public/Going-the-Extra-Mile.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Grotz, J.; Ledgard, M.; Poland, F. Patient and Public Involvement in Health and Social Care Research: An Introduction to Theory and Practice; Palgrave Macmillian: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, J.; Dawes, P.; Edwards, S.; Leroi, I.; Starling, B.; Parsons, S. Patient and public involvement in dementia research in the European Union: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, F.; Charlesworth, G.; Leung, P.; Birt, L. Embedding patient and public involvement: Managing tacit and explicit expectations. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford-Dent, J.; Sprange, K.; Mountain, G.; Mason, C.; Wright, J.; Craig, C.; Birt, L. Embedding patient and public involvement in dementia research: Reflections from experiences during the ‘Journeying through Dementia’ randomised controlled trial. Dementia 2022, 21, 1987–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gove, D.; Diaz-Ponce, A.; Georges, J.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Mountain, G.; Chattat, R.; Øksnebjerg, L.; The European Working Group of People with Dementia. Alzheimer Europe’s position on involving people with dementia in research through PPI (patient and public involvement). Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Lach, L.; King, G.; Scott, M.; Boydell, K.; Sawatzky, B.J.; Reisman, J.; Schippel, E.; Young, N.L. Contrasting internet and face-to-face focus groups for children with chronic health conditions: Outcomes and participant experiences. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2010, 9, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; O’Regan, A.; Godwin, C.; Taylor, J. Comparing Interview and Focus Group Data Collected in Person and Online; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.; Mill, D.; Johnson, J.; Lee, K. Let’s talk virtual! Online focus group facilitation for the modern researcher. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2145–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, C.; Kevern, J. Focus groups as a research method: A critique of some aspects of their use in nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 33, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Sambrook, S.; Irvine, F. The phenomenological focus group: An oxymoron? J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novek, S.; Wilkinson, H. Safe and inclusive research practices for qualitative research involving people with dementia: A review of key issues and strategies. Dementia 2019, 18, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A. The future of focus groups. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Grocke, D.; Dileo, C. The use of group descriptive phenomenology within a mixed methods study to understand the experience of music therapy for women with breast cancer. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2017, 26, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundler, A.J.; Lindberg, E.; Nilsson, C.; Palmér, L. Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonde, L.O. Health musicing—Music therapy or music and health? A model, empirical examples and personal reflections. Music. Arts Action 2011, 3, 120–140. [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Cortés, A.; Pranjić, M.; Knott, D.; Mercadal-Brotons, M.; Fuller, A.; Kelly, L.; Selvarajah, I.; Vaudreuil, R. International Music Therapists’ Perceptions and Experiences in Telehealth Music Therapy Provision. Int. J. Environ Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, B. Music for life’s journey: The capacity of music in dementia care. Alzheimer’s Care Today 2009, 10, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Music Experiences | Dementia | Context |

|---|---|---|

| “Choir” OR “group singing” OR “Music” OR “music-based interventions” OR “music listening” OR “music activities” OR “musical instrument” OR “music therapy” OR “playlist” OR “singing” | “Alzheimer *” OR “cognitive impairment” OR “cognitive decline” OR “dementia” OR “older adults” | “Community” OR “community dwelling” OR “dwelling” OR “home” OR “home-based” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kelly, L.; Clements-Cortés, A.; Ahessy, B.; Richardson, I.; Moss, H. “Follow the Musical Road”: Selecting Appropriate Music Experiences for People with Dementia Living in the Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105818

Kelly L, Clements-Cortés A, Ahessy B, Richardson I, Moss H. “Follow the Musical Road”: Selecting Appropriate Music Experiences for People with Dementia Living in the Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105818

Chicago/Turabian StyleKelly, Lisa, Amy Clements-Cortés, Bill Ahessy, Ita Richardson, and Hilary Moss. 2023. "“Follow the Musical Road”: Selecting Appropriate Music Experiences for People with Dementia Living in the Community" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105818

APA StyleKelly, L., Clements-Cortés, A., Ahessy, B., Richardson, I., & Moss, H. (2023). “Follow the Musical Road”: Selecting Appropriate Music Experiences for People with Dementia Living in the Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105818