Substance Use and Psychological Distress in Mexican Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Substance Use

3.2. Psychological Impact

3.3. Gender Differences

4. Discussion

4.1. Substances Used

4.2. Psychological Effects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zainel, A.A.; Qotba, H.; Al-Maadeed, A.; Al-Kohji, S.; Al Mujalli, H.; Ali, A.; Al Mannai, L.; Aladab, A.; AlSaadi, H.; AlKarbi, K.A.; et al. Psychological and Coping Strategies Related to Home Isolation and Social Distancing in Children and Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e24760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data|WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Social Impact of COVID-19; The United Nation Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, R. Chronic Stress, Drug Use, and Vulnerability to Addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J. Lifetime and 1-Year Prevalence of Homelessness in the US Population: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J. Public Health 2018, 40, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, B.; Beynon, C.; Pickering, L.; Duffy, P. Experiences of Drug Use and Ageing: Health, Quality of Life, Relationship and Service Implications. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vélez, N.A.; Tiburcio, M.; Natera Rey, G.; Villatoro Velázquez, J.A.; Arroyo-Belmonte, M.; Sánchez-Hernández, G.Y.; Fernández-Torres, M. Psychoactive Substance Use and Its Relationship to Stress, Emotional State, Depressive Symptomatology, and Perceived Threat During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 709410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Chainé, S.; López Montoya, A.; Bosch Maldonado, A.; Beristain Aguirre, A.; Robles García, R.; Garibay Rubio, C.R.; Astudillo García, C.I.; Lira Chávez, I.A.; Rangel Gómez, M.G. Mental Health Symptoms, Binge Drinking, and the Experience of Abuse During the COVID-19 Lockdown in Mexico. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, J.N.; Boggero, I.A.; Scott, A.B.; Segerstrom, S.C. Current Directions in Stress and Human Immune Function. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Moura, H.F.; Scherer, J.N.; Pechansky, F.; Kessler, F.H.P.; von Diemen, L. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Substance Use: Implications for Prevention and Treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J. 12 Rules for Life; Penguin UK: London, UK, 2018; Volume 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, C.; Cowell, A.J.; Dowd, W.N. Alcohol Consumption in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J. Addict. Med. 2021, 15, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, J.; Kilian, C.; Carr, S.; Bartak, M.; Bloomfield, K.; Braddick, F.; Gual, A.; Neufeld, M.; O’Donnell, A.; Petruzelka, B.; et al. Use of Alcohol, Tobacco, Cannabis, and Other Substances during the First Wave of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Europe: A Survey on 36,000 European Substance Users. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2021, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallie, S.N.; Ritou, V.; Bowden-Jones, H.; Voon, V. Assessing International Alcohol Consumption Patterns during Isolation from the COVID-19 Pandemic Using an Online Survey: Highlighting Negative Emotionality Mechanisms. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e044276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantis, K.; Panagiotidis, P.; Parlapani, E.; Holeva, V.; Tsapakis, E.M.; Diakogiannis, I. Substance Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. J. Subst. Use 2021, 27, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2017 NSDUH Annual National Report. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2017-nsduh-annual-national-report (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Varela, J.A.; Leticia, D.N.; Melgoza, F.; Arístides, L.; Bautista, B.; Lizbeth, M.; Quevedo, R.G.; Nadia, M.; Soto, R.; Alejandra, L.; et al. Current Drug Consumption Report in Mexico; Government of Mexico: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, T.; Corrigan, M.J.; Coffey, K.; Tronnier, C.D.; Wang, D.; Krase, K. Exploring Factors Associated with Alcohol and/or Substance Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A Brief Mental Health Screener for COVID-19 Related Anxiety. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Magaña, I.; Lee, S.A.; Maldonado-Castellanos, I.; Jiménez-Gutierrez, C.; Mendez-Venegas, J.; Maya-Del-Moral, A.; Rosas-Munive, M.D.; Mathis, A.A.; Jobe, M.C. Coronaphobia among Healthcare Professionals in Mexico: A Psychometric Analysis. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador Jiménez, D.E. La Pandemia Del COVID-19, Su Impacto En La Salud Mental y El Consumo de Sustancias. Rev. Humanismo Cambio Soc. 2020, 16, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional contra las Adicciones. Informe Sobre La Situación Del Consumo de Drogas En Mexico. Secr. Salud Com. Nac. Contra Adicciones 2019, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Papiernik, M.; Mikulska, A.; Czarkowska-Paczek, B. Smoking, Alcohol Consumption, and Illicit Substances Use among Adolescents in Poland. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2018, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.; Laks, J.; Coutinho, E.S.F.; Blay, S.L. Tobacco Use among the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cad. Saude Publica 2010, 26, 2213–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, N.; Choi, E.; Choi, J.; Suk, H.W.; Na, J. How COVID-19 Affected Mental Well-Being: An 11- Week Trajectories of Daily Well-Being of Koreans amidst COVID-19 by Age, Gender and Region. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, Y.; Okawara, M.; Hino, A.; Nagata, T.; Muramatsu, K.; Tateishi, S.; Tsuji, M.; Ogami, A.; Yoshimura, R.; Fujino, Y. Association of Alcohol Consumption and Frequency with Loneliness: A Cross-Sectional Study among Japanese Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, M.J.; Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Biswas, P.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, S. COVID-19 and Addiction. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaksen, T.; Ekeberg, Ø.; Schou-Bredal, I.; Skogstad, L.; Heir, T.; Grimholt, T.K. Use of Alcohol and Addictive Drugs During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Norway: Associations with Mental Health and Pandemic-Related Problems. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deimel, D.; Firk, C.; Stöver, H.; Hees, N.; Scherbaum, N.; Fleißner, S. Substance Use and Mental Health during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Germany: Results of a Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecksher, D.; Hesse, M. Women and Substance Use Disorders. Mens. Sana Monogr. 2009, 7, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Rogers, J.; Mason, R.; Siriwardena, A.N.; Hogue, T.; Whitley, G.A.; Law, G.R. Alcohol and Other Substance Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 229, 109150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, H.M.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Halldorsdottir, T.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Allegrante, J.P.; Kristjansson, A.L. Substance Use Among Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2022, 24, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Men | 326 (37.6%) | |

| Women | 540 (62.4%) | |

| Age, mean (standard deviation) | 35.12 ± 13.31 | |

| Educational degree, n (%) | ||

| University degree | 569 (65.7%) | |

| Master’s degree | 92 (10.6%) | |

| Trade school | 79 (9.1%) | |

| High school | 75 (8.7%) | |

| Doctorate | 18 (2.1%) | |

| Middle school | 23 (2.7%) | |

| Post-doctorate | 6 (0.7%) | |

| Primary school | 4 (0.5%) | |

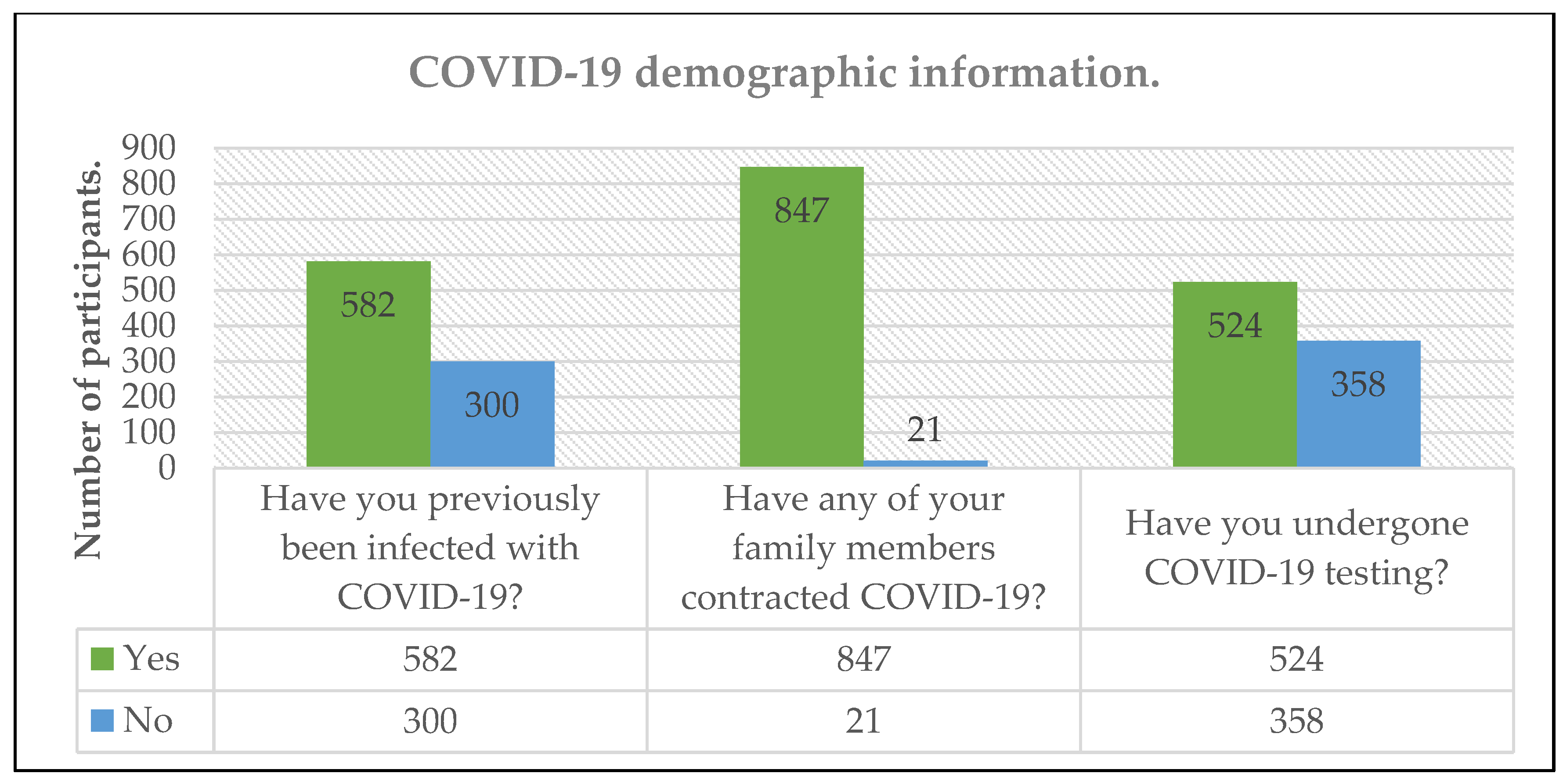

| COVID-19 infection, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 582 (66%) | |

| No | 300 (34%) | |

| COVID-19-positive acquaintance, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 847 (97.5%) | |

| No | 21 (2.4%) | |

| COVID-19 testing, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 524 (59.4%) | |

| No | 358 (40.5%) | |

| Number of days between test and onset of symptoms | ||

| <15 days | 482 (92%) | |

| >15 days | 42 (8%) | |

| Substance | Number of Users before the Pandemic | Number of Users during the Pandemic | Percentage Change | p Value | df | χ2 | Unit of Measurement | Mean Use/Dose before the Pandemic | Mean Use/Dose during the Pandemic | Percentage Change | p Value | df | t Score | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 165 | 172 | 4.24% | 0.457 | 1 | 0.55 | Glass (350 mL/day) | 1.68 ± 1.63 | 2.06 ± 2.13 | 22.62% | 0.006 | 136 | −2.783 | 0.20 |

| Tobacco | 143 | 127 | −11.19% | 0.001 | 1 | 41.65 | Cigarettes/day | 15.85 ± 21.60 | 20.76 ± 29.85 | 30.98% | 0.001 | 105 | −3.889 | 0.18 |

| Marijuana | 49 | 50 | 2.04% | 1.000 | 1 | 0.00 | Cigarettes/week | 2.80 ± 3.06 | 3.93 ± 6.32 | 40.36% | 0.139 | 34 | −1.514 | 0.38 |

| OTC Drugs | Number of users before the pandemic | Number of users during the pandemic | Percentage change | p value | df | χ2 | Unit of measurement | Mean use/dose before the pandemic | Mean use/dose during the pandemic | Percentage change | p value | df | t score | Cohen’s d |

| Alcohol | 165 | 172 | 4.24% | 0.457 | 1 | 0.55 | Glass (350 mL/day) | 1.68 ± 1.63 | 2.06 ± 2.13 | 22.62% | 0.006 | 136 | −2.783 | 0.20 |

| Tobacco | 143 | 127 | −11.19% | 0.001 | 1 | 41.65 | Cigarettes/day | 15.85 ± 21.60 | 20.76 ± 29.85 | 30.98% | 0.001 | 105 | −3.889 | 0.18 |

| Marijuana | 49 | 50 | 2.04% | 1.000 | 1 | 0.00 | Cigarettes/week | 2.80 ± 3.06 | 3.93 ± 6.32 | 40.36% | 0.139 | 34 | −1.514 | 0.38 |

| Previous Psychiatric Diagnosis, n (%) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | 95 (10.96%) |

| Depression | 76 (8.77%) |

| Empathy-associated burnout syndrome | 2 (0.23%) |

| Panic disorder | 4 (0.46%) |

| Psychotic disorder | 1 (0.11%) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 4 (0.46%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (0.11%) |

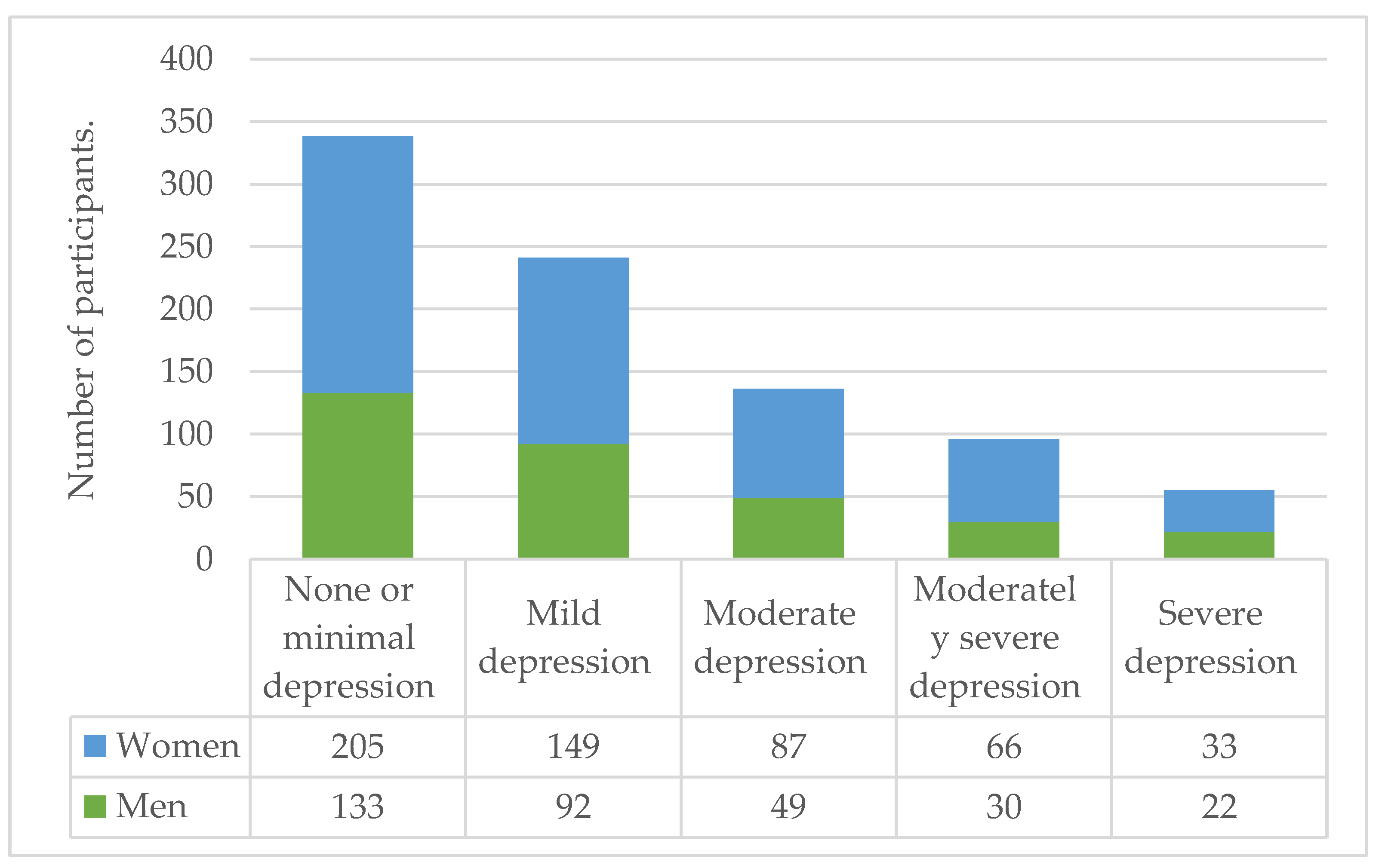

| PHQ-9 | |

| Mean scores | 7.74 ± 6.48 |

| None or minimal depression | 235 (27.1%) |

| Mild depression | 245 (25.5%) |

| Moderate depression | 111 (12.8%) |

| Moderately severe depression | 96 (11%) |

| Severe depression | 73 (8.4%) |

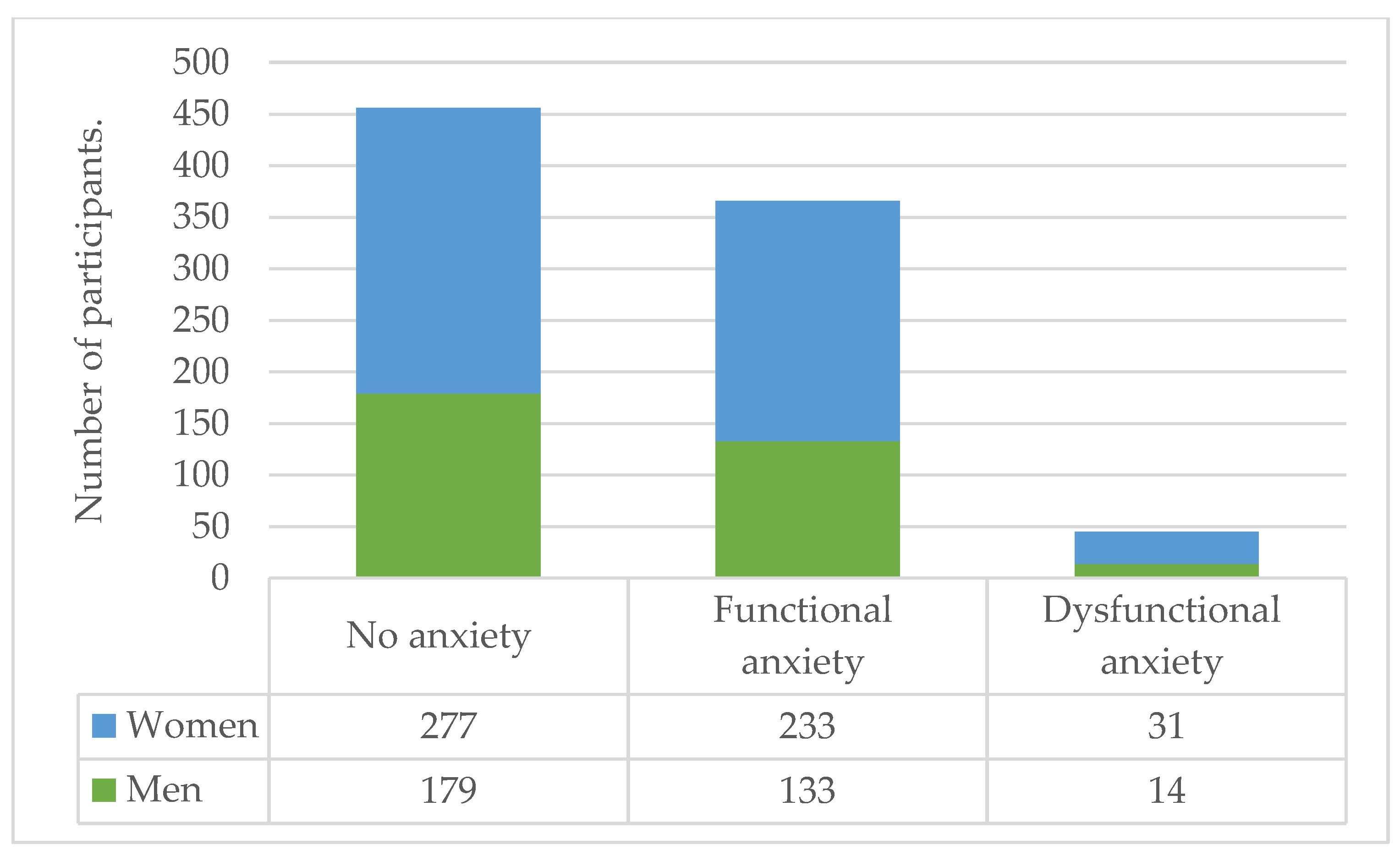

| CAS | |

| Mean score | 1.66 ± 2.82 |

| No anxiety | 464 (52.6%) |

| Functional anxiety | 373 (42.3%) |

| Dysfunctional anxiety | 45 (5.1%) |

| Felt overwhelmed by the amount of information on COVID-19 | |

| Yes | 649 (74.7%) |

| No | 219 (25.2%) |

| Felt prepared for the pandemic | |

| Yes | 67 (7.7%) |

| No | 801 (92.2%) |

| Substance | PHQ-9 Mean Scores | p Value | df | t Score | Cohen’s d | CAS Mean Scores | p Value | df | t Score | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any substance | ||||||||||

| Yes | 8.22 ± 6.61 | 0.236 | 864 | −1.187 | 0.08 | 1.77 ± 2.87 | 0.445 | 864 | −0.765 | 0.06 |

| No | 7.63 ± 6.45 | 1.60 ± 2.79 | ||||||||

| Alcohol | ||||||||||

| Yes | 8.44 ± 6.80 | 0.140 | 864 | 0.589 | 0.12 | 1.88 ± 3.06 | 0.214 | 864 | 1.245 | 0.09 |

| No | 7.63 ± 6.41 | 1.59 ± 2.75 | ||||||||

| Tobacco | ||||||||||

| Yes | 8.12 ± 6.47 | 0.644 | 864 | 0.462 | 0.05 | 1.66 ± 2.73 | 0.969 | 864 | 0.038 | 0.07 |

| No | 7.76 ± 6.50 | 1.64 ± 2.82 | ||||||||

| Marijuana | ||||||||||

| Yes | 8.12 ± 5.87 | 0.710 | 864 | −0.372 | 0.05 | 1.68 ± 2.30 | 0.938 | 864 | −0.077 | 0.01 |

| No | 7.77 ± 6.53 | 1.64 ± 2.84 |

| Alcohol Consumption | Men (n = 326) | Women (n = 540) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | 40 (12.3%) | 45 (8.3%) | 0.040 |

| No increase | 286 (87.7%) | 495 (91.7%) | |

| Marijuana consumption | |||

| Increase | 13 (4%) | 18 (3.3%) | 0.706 |

| No increase | 313 (96%) | 522 (96.7%) | |

| Coffee consumption | |||

| Increase | 59 (18.1%) | 149 (27.6%) | 0.002 |

| No increase | 267 (81.9%) | 391 (72.4%) | |

| Tobacco consumption | |||

| Increase | 34 (10.4%) | 40 (7.4%) | 0.133 |

| No increase | 292 (89.6%) | 500 (92.6%) | |

| PHQ-9 | |||

| Mean scores | 8.79 ± 6.20 | 8.94 ± 6.20 | 0.735 |

| CAS | |||

| Mean scores | 3.44 ± 2.91 | 3.50 ± 3.39 | 0.865 |

| Felt overwhelmed by amount of information on COVID-19 | |||

| Yes | 201 (61.7%) | 440 (81.5%) | 0.001 |

| No | 125 (38.3%) | 100 (18.5%) | |

| Felt prepared for the pandemic | |||

| Yes | 58 (17.8%) | 21 (3.9%) | 0.001 |

| No | 268 (82.2%) | 519 (96.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibarrola-Peña, J.C.; Cueto-Valadez, T.A.; Chejfec-Ciociano, J.M.; Cifuentes-Andrade, L.R.; Cueto-Valadez, A.E.; Castillo-Cardiel, G.; Cervantes-Cardona, G.A.; Cervantes-Pérez, E.; Cervantes-Guevara, G.; Guzmán-Ruvalcaba, M.J.; et al. Substance Use and Psychological Distress in Mexican Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010716

Ibarrola-Peña JC, Cueto-Valadez TA, Chejfec-Ciociano JM, Cifuentes-Andrade LR, Cueto-Valadez AE, Castillo-Cardiel G, Cervantes-Cardona GA, Cervantes-Pérez E, Cervantes-Guevara G, Guzmán-Ruvalcaba MJ, et al. Substance Use and Psychological Distress in Mexican Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010716

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbarrola-Peña, Juan Carlos, Tania Abigail Cueto-Valadez, Jonathan Matías Chejfec-Ciociano, Luis Rodrigo Cifuentes-Andrade, Andrea Estefanía Cueto-Valadez, Guadalupe Castillo-Cardiel, Guillermo Alonso Cervantes-Cardona, Enrique Cervantes-Pérez, Gabino Cervantes-Guevara, Mario Jesús Guzmán-Ruvalcaba, and et al. 2023. "Substance Use and Psychological Distress in Mexican Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010716

APA StyleIbarrola-Peña, J. C., Cueto-Valadez, T. A., Chejfec-Ciociano, J. M., Cifuentes-Andrade, L. R., Cueto-Valadez, A. E., Castillo-Cardiel, G., Cervantes-Cardona, G. A., Cervantes-Pérez, E., Cervantes-Guevara, G., Guzmán-Ruvalcaba, M. J., Sapién-Fernández, J. H., Guzmán-Barba, J. A., Esparza-Estrada, I., Flores-Becerril, P., Brancaccio-Pérez, I. V., Guzmán-Ramírez, B. G., Álvarez-Villaseñor, A. S., Barbosa-Camacho, F. J., Reyes-Elizalde, E. A., ... González-Ojeda, A. (2023). Substance Use and Psychological Distress in Mexican Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010716