Awareness Status of Schistosomiasis among School-Aged Students in Two Schools on Pemba Island, Zanzibar: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

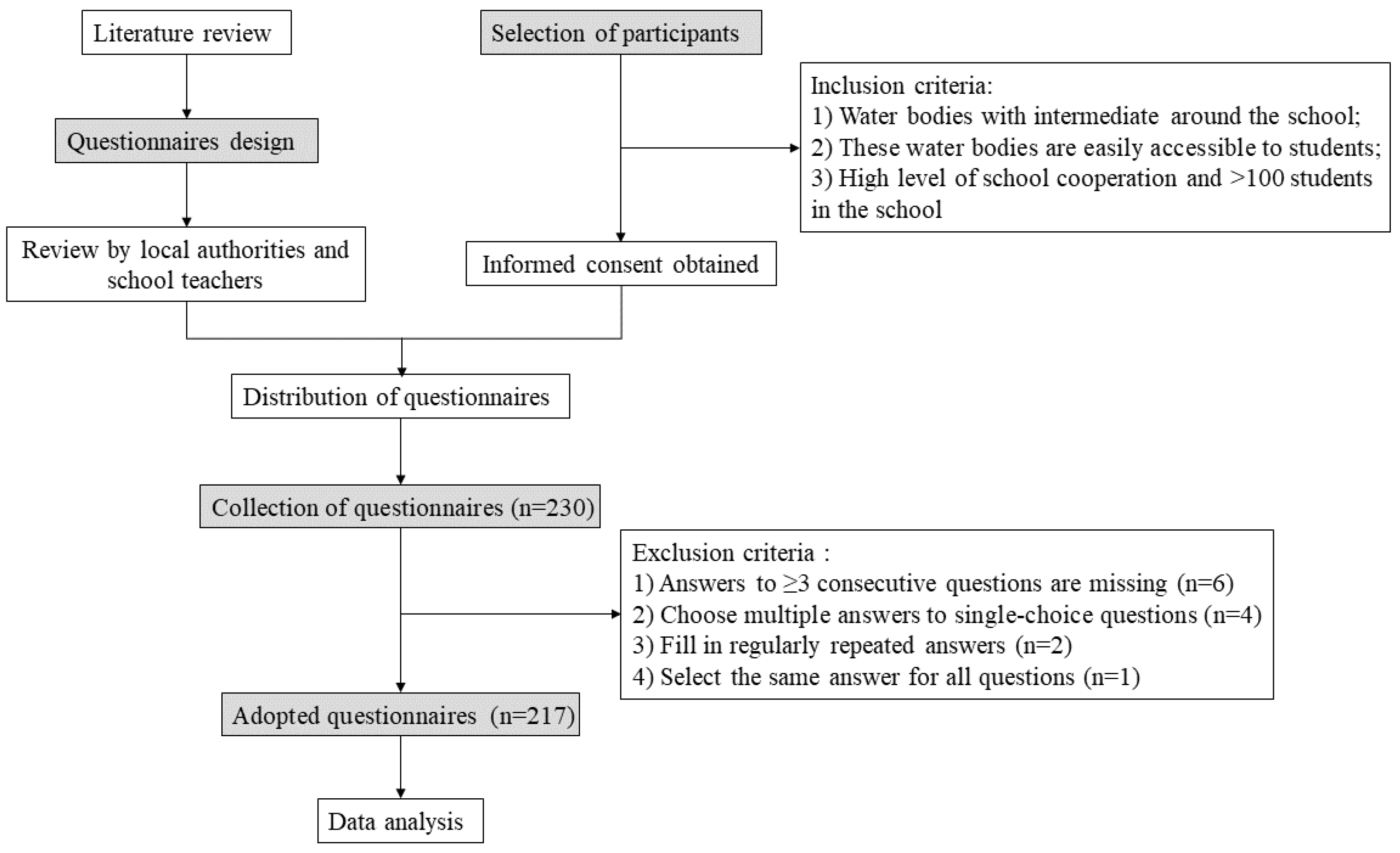

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Public Involvement

2.2. Questionnaire Survey

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Knowledge about Schistosomiasis

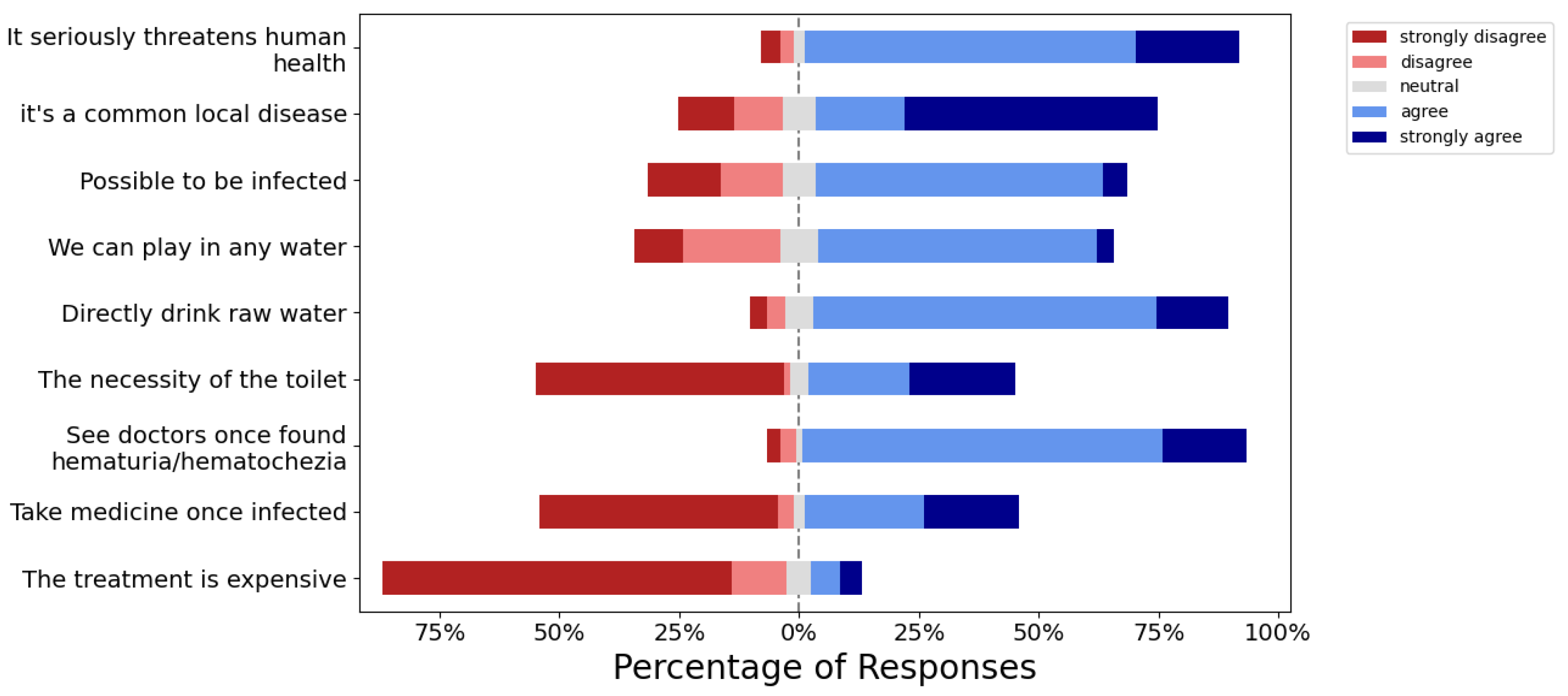

3.3. Attitude towards Schistosomiasis

3.4. Practice Related to Schistosomiasis

3.5. Factors Associated with KAP of Schistosomiasis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- McManus, D.P.; Dunne, D.W.; Sacko, M.; Utzinger, J.; Vennervald, B.J.; Zhou, X.N. Schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopp, S.; Mohammed, K.A.; Ali, S.M.; Khamis, I.S.; Ame, S.M.; Albonico, M.; Gouvras, A.; Fenwick, A.; Savioli, L.; Colley, D.G.; et al. Study and implementation of urogenital schistosomiasis elimination in Zanzibar (Unguja and Pemba islands) using an integrated multidisciplinary approach. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Juma, S.; Kabole, F.; Guo, J.; Garba, A.; He, J.; Dai, J.-R.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.-F. China-Zanzibar Cooperation Project of Schistosomiasis Control: Study Design. In Sino-African Cooperation for Schistosomiasis Control in Zanzibar; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 15, pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Nassiwa, J.H.D.-C.X.R. A Package of Health Education Materials: Effectiveness for Schistosomiasis Control in Zanzibar. In Sino-African Cooperation for Schistosomiasis Control in Zanzibar; Mehlhorn, K.Y.H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 15, pp. 179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Person, B.; Rollinson, D.; Ali, S.M.; Mohammed, U.A.; A’Kadir, F.M.; Kabole, F.; Knopp, S. Evaluation of a urogenital schistosomiasis behavioural intervention among students from rural schools in Unguja and Pemba islands, Zanzibar. Acta Trop. 2021, 220, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazigo, H.D.; Nuwaha, F.; Kinung’hi, S.M.; Morona, D.; Pinot de Moira, A.; Wilson, S.; Heukelbach, J.; Dunne, D.W. Epidemiology and control of human schistosomiasis in Tanzania. Parasit Vectors 2012, 5, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelo, T.; Kinung’hi, S.M.; Buza, J.; Mwanga, J.R.; Kariuki, H.C.; Wilson, S. Community knowledge, perceptions and water contact practices associated with transmission of urinary schistosomiasis in an endemic region: A qualitative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yang, K. The Global Status and Control of Human Schistosomiasis: An Overview. In Sino-African Cooperation for Schistosomiasis Control in Zanzibar; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Jukes, M.C.; Nokes, C.A.; Alcock, K.J.; Lambo, J.K.; Kihamia, C.; Ngorosho, N.; Mbise, A.; Lorri, W.; Yona, E.; Mwanri, L.; et al. Heavy schistosomiasis associated with poor short-term memory and slower reaction times in Tanzanian schoolchildren. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2002, 7, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseko, T.S.B.; Mkhonta, N.R.; Masuku, S.K.S.; Dlamini, S.V.; Fan, C.K. Schistosomiasis knowledge, attitude, practices, and associated factors among primary school children in the Siphofaneni area in the Lowveld of Swaziland. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2018, 51, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Schistosomiasis: Progress Report 2001–2011 and Strategic Plan 2012–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- WHO. WHO Guideline on Control and Elimination of Human Schistosomiasis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- WHO. Schistosomiasis Situational Analyses, Core Implementation Data and Trend Data Are Provided through Direct access to the Interactive Reports; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/data-platforms/pct-databank/schistosomiasis (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Onasanya, A.; Bengtson, M.; Oladepo, O.; Van Engelen, J.; Diehl, J.C. Rethinking the Top-Down Approach to Schistosomiasis Control and Elimination in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 622809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Xing, Y.; Abdalla, F.M. The Novel Strategy of China-Zanzibar Cooperation Project of Schistosomiasis Control: The Integrated Strategy. In Sino-African Cooperation for Schistosomiasis Control in Zanzibar; Mehlhorn, K.Y.H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 15, pp. 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Alharazi, T.H.; Al-Mekhlafi, H.M. A cross-sectional survey of the knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding schistosomiasis among rural schoolchildren in Taiz governorate, southwestern Yemen. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, R.; Njenga, S.M.; Ichinose, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Estrada, C.A.; Kobayashi, J. Is there a gap between health education content and practice toward schistosomiasis prevention among schoolchildren along the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacolo-Gwebu, H.; Kabuyaya, M.; Chimbari, M. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths among caregivers in Ingwavuma area in uMkhanyakude district, South Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lothe, A.; Zulu, N.; Øyhus, A.O.; Kjetland, E.F.; Taylor, M. Treating schistosomiasis among South African high school pupils in an endemic area, a qualitative study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munisi, D.Z.; Buza, J.; Mpolya, E.A.; Angelo, T.; Kinung’hi, S.M. Knowledge, attitude, and practices on intestinal schistosomiasis among primary schoolchildren in the Lake Victoria basin, Rorya District, north-western Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angrist, N.; de Barros, A.; Bhula, R.; Chakera, S.; Cummiskey, C.; DeStefano, J.; Floretta, J.; Kaffenberger, M.; Piper, B.; Stern, J. Building back better to avert a learning catastrophe: Estimating learning loss from COVID-19 school shutdowns in Africa and facilitating short-term and long-term learning recovery. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 84, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassi, C.; Martin, S.; Graham, K.; de Cola, M.A.; Christiansen-Jucht, C.; Smith, L.E.; Jive, E.; Phillips, A.E.; Newell, J.N.; Massangaie, M. Knowledge, attitudes and practices with regard to schistosomiasis prevention and control: Two cross-sectional household surveys before and after a Community Dialogue intervention in Nampula province, Mozambique. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyeneho, N.G.; Yinkore, P.; Egwuage, J.; Emukah, E. Perceptions, attitudes and practices on schistosomiasis in Delta State, Nigeria. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 2010, 12, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Person, B.; Ali, S.M.; A’Kadir, F.M.; Ali, J.N.; Mohammed, U.A.; Mohammed, K.A.; Rollinson, D.; Knopp, S. Community Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices Associated with Urogenital Schistosomiasis among School-Aged Children in Zanzibar, United Republic of Tanzania. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odhiambo, G.O.; Musuva, R.M.; Odiere, M.R.; Mwinzi, P.N. Experiences and perspectives of community health workers from implementing treatment for schistosomiasis using the community directed intervention strategy in an informal settlement in Kisumu City, western Kenya. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adekeye, O.; Ozano, K.; Dixon, R.; Elhassan, E.O.; Lar, L.; Schmidt, E.; Isiyaku, S.; Okoko, O.; Thomson, R.; Theobald, S.; et al. Mass administration of medicines in changing contexts: Acceptability, adaptability and community directed approaches in Kaduna and Ogun States, Nigeria. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (217) | ≤15 | 121 (55.76) |

| >15 | 96 (44.24) | |

| Sex (217) | Male | 89 (41.01) |

| Female | 128 (58.99) | |

| Residence (217) | Mtangani | 130 (59.91) |

| Uwandani | 87 (40.09) | |

| Grade (217) | Primary | 73 (33.64) |

| Secondary | 144 (66.36) | |

| Family size (173) | <5 | 39 (22.54) |

| 5~10 | 56 (32.37) | |

| >10 | 78 (45.09) | |

| Caregiver (204) | Father | 95 (46.57) |

| Mother | 88 (43.14) | |

| Grandparents | 18 (8.82) | |

| Others | 3 (1.47) | |

| Infection status (217) | Yes | 40 (18.43) |

| No | 113 (52.07) | |

| No idea | 64 (29.49) | |

| Father’s education (217) | Illiteracy | 36 (16.59) |

| Primary | 68 (31.34) | |

| Secondary and higher | 65 (29.95) | |

| No idea | 48 (22.12) | |

| Mother’s education (217) | Illiteracy | 40 (18.43) |

| Primary | 58 (26.73) | |

| Secondary and higher | 83 (38.25) | |

| No idea | 36 (16.59) | |

| Father’s occupation (217) | Farmer | 169 (77.88) |

| Government staff | 16 (7.37) | |

| Others | 32 (14.95) | |

| Mother’s occupation (217) | Farmer | 150 (69.12) |

| Government staff | 12 (5.53) | |

| Others | 55 (25.35) | |

| Blood in urine or not (217) | Yes | 42 (19.35) |

| No | 175 (80.65) |

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Schistosomiasis is one kind of parasites diseases (217) | |

| True | 209(96.31) |

| False | 8(3.69) |

| What types of schistosomiases are included (217) | |

| Intestinal schistosomiasis | 3(1.38) |

| Urinary schistosomiasis | 198(91.24) |

| Both | 11(5.07) |

| No idea | 5(2.30) |

| What are the signs and symptoms of schistosomiasis (217) | |

| Abdominal pain | 2(0.92) |

| Diarrhea | 4(1.84) |

| Bloody stool | 149(68.66) |

| Hematuria | 53(24.42) |

| Vomiting | 3(1.38) |

| Weakness | 1(0.46) |

| Odynuria | 1(0.46) |

| No idea | 4(1.84) |

| How can a person develop schistosomiasis (217) | |

| Contact with contaminated water | 153(70.51) |

| Eating raw or undercooked fish/meat | 4(1.84) |

| Eating unwashed vegetables | 8(3.69) |

| Close contact with schistosomiasis | 11(5.07) |

| No idea | 42(19.35) |

| Snails are able to transmit schistosomiasis (217) | |

| True | 66(30.41) |

| False | 151(69.59) |

| Schistosomiasis is curable (217) | |

| True | 203(93.55) |

| False | 14(6.45) |

| Schistosomiasis is preventable (217) | |

| True | 208(95.85) |

| False | 9(4.15) |

| How do the controls and prevention work in your locality (217) | |

| Snail extermination | 26(11.98) |

| Setting up voice prompters | 156(71.89) |

| Building water pipes | 16(7.37) |

| Science brochure | 8(3.69) |

| No idea | 19(8.76) |

| Variable | Knowledge | Attitude | Practice | Total Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | p | |

| Age | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.07 | <0.01 | ||||

| ≤15 | 6.67(1.05) | 30.88(2.64) | 12.89(1.76) | 50.44(3.28) | ||||

| >15 | 6.99(0.85) | 32.59(3.50) | 13.31(1.61) | 52.90(4.10) | ||||

| Sex | 0.58 | 0.81 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 6.76(1.17) | 31.57(3.12) | 12.25(1.67) | 50.58(3.67) | ||||

| Female | 6.84(0.83) | 31.68(3.20) | 13.66(1.48) | 52.18(3.86) | ||||

| Residence | 0.08 | <0.01 | 0.38 | <0.01 | ||||

| Mtangni | 6.72(1.02) | 30.93(2.72) | 15.78(1.89) | 53.43(3.54) | ||||

| Uwandani | 6.95(0.90) | 32.69(3.48) | 16.02(2.01) | 55.67(4.20) | ||||

| Family size | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| <5 | 6.85(0.88) | 32.46(2.99) | 13.72(1.43) | 53.03(3.67) | ||||

| 5–10 | 6.98(0.77) | 31.88(3.36) | 12.77(1.96) | 51.63(3.98) | ||||

| >10 | 6.78(1.17) | 30.92(3.18) | 13.04(1.73) | 50.74(3.81) | ||||

| Caregiver | 0.73 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||

| Father | 6.86(0.79) | 31.05(2.46) | 13.26(1.78) | 51.18(3.24) | ||||

| Mother | 6.80(1.03) | 32.59(3.23) | 13.36(1.50) | 52.75(3.69) | ||||

| Grandparents | 6.56(1.58) | 30.11(4.42) | 11.78(1.52) | 48.44(5.10) | ||||

| Others | 6.88(0.89) | 31.56(3.58) | 11.88(1.50) | 54.00(1.00) | ||||

| Infection status | 0.59 | 0.89 | <0.01 | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 6.93(0.66) | 31.60(2.88) | 11.58(1.60) | 50.10(3.49) | ||||

| No | 6.80(0.91) | 31.56(3.06) | 13.60(1.50) | 51.96(3.66) | ||||

| Unclear | 6.77(1.24) | 31.80(3.52) | 13.09(1.57) | 51.66(4.23) | ||||

| Father’s education | 0.69 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.56 | ||||

| Illiteracy | 6.83(0.56) | 31.58(2.14) | 13.08(1.96) | 51.50(3.15) | ||||

| Primary | 6.81(1.20) | 31.88(3.66) | 12.99(1.59) | 51.68(4.40) | ||||

| Secondary and higher | 6.82(0.88) | 31.94(3.68) | 12.92(1.58) | 51.68(4.24) | ||||

| No idea | 6.79(1.03) | 30.92(2.04) | 13.42(1.82) | 51.13(2.94) | ||||

| Mother’s education | 0.72 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.76 | ||||

| Illiteracy | 6.83(0.96) | 32.03(3.65) | 13.03(1.63) | 51.88(3.58) | ||||

| Primary | 6.71(0.77) | 31.67(3.37) | 13.41(1.59) | 51.79(4.25) | ||||

| Secondary and higher | 6.82(1.10) | 31.70(3.18) | 12.70(1.74) | 51.22(4.10) | ||||

| No idea | 6.94(1.04) | 31.00(2.00) | 13.47(1.77) | 51.42(2.84) | ||||

| Father’s occupation | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.12 | ||||

| Farmer | 6.87(1.00) | 31.62(2.86) | 13.05(1.71) | 51.54(3.50) | ||||

| Government staff | 6.63(1.09) | 33.00(5.90) | 13.44(1.41) | 53.06(7.27) | ||||

| Others | 6.59(0.76) | 31.03(2.65) | 13.06(1.83) | 50.69(3.13) | ||||

| Mother’s occupation | 0.12 | <0.01 | 0.43 | 0.03 | ||||

| Farmer | 6.90(1.02) | 32.01(3.07) | 12.98(1.67) | 51.89(3.63) | ||||

| Government staff | 6.75(0.97) | 32.00(6.15) | 13.17(1.47) | 51.92(8.06) | ||||

| Others | 6.58(0.83) | 30.53(2.12) | 13.33(1.85) | 50.44(2.87) | ||||

| Blood in urine or not | 0.87 | 0.97 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 6.83(0.73) | 31.62(2.91) | 11.33(1.68) | 49.79(3.89) | ||||

| No | 6.81(1.03) | 31.64(3.22) | 13.50(1.43) | 51.94(3.74) | ||||

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | p | 95%CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Se | β | t | ||||

| Attitude | Constant | 31.32 | 1.08 | 29.05 | <0.01 | (29.19, 33.45) | |

| Age | 1.24 | 0.50 | 0.19 | 2.48 | 0.01 | (0.25, 2.22) | |

| Family size | −0.64 | 0.31 | −0.16 | −2.07 | 0.04 | (−1.26, −0.03) | |

| Practice | Constant | 8.05 | 0.62 | 12.90 | <0.01 | (6.81, 9.28) | |

| Hematuria | 2.16 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 7.78 | <0.01 | (1.61, 2.71) | |

| Sex | 1.15 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 5.22 | <0.01 | (0.71, 1.58) | |

| Caregiver | −0.34 | 0.15 | −0.14 | −2.29 | 0.02 | (−0.64, −0.05) | |

| Total score | Constant | 47.67 | 1.77 | 26.98 | <0.01 | (44.18, 51.16) | |

| Age | 2.09 | 0.58 | 0.27 | 3.64 | <0.01 | (0.96, 3.23) | |

| Family size | −0.90 | 0.36 | −0.19 | −2.51 | 0.01 | (−1.60, −0.19) | |

| Hematuria | 1.67 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 2.29 | 0.02 | (0.23, 3.12) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Hu, W.; Saleh, J.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Q.; Wu, H.; Yang, K.; Huang, Y. Awareness Status of Schistosomiasis among School-Aged Students in Two Schools on Pemba Island, Zanzibar: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010582

Liu Y, Hu W, Saleh J, Wang Y, Xue Q, Wu H, Yang K, Huang Y. Awareness Status of Schistosomiasis among School-Aged Students in Two Schools on Pemba Island, Zanzibar: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):582. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010582

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yiyun, Wenjun Hu, Juma Saleh, Yuyan Wang, Qingkai Xue, Hongchu Wu, Kun Yang, and Yuzheng Huang. 2023. "Awareness Status of Schistosomiasis among School-Aged Students in Two Schools on Pemba Island, Zanzibar: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010582

APA StyleLiu, Y., Hu, W., Saleh, J., Wang, Y., Xue, Q., Wu, H., Yang, K., & Huang, Y. (2023). Awareness Status of Schistosomiasis among School-Aged Students in Two Schools on Pemba Island, Zanzibar: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010582