Government Environmental Regulation and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Natural Resource Accountability Audits in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Research on AANR

2.1.2. Research on Corporate ESG Performance

2.1.3. Research on the Impact of AANR on Corporate ESG Performance

2.2. Hypothesis

3. Study Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics Results

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1. Results of Baseline Regression Analysis

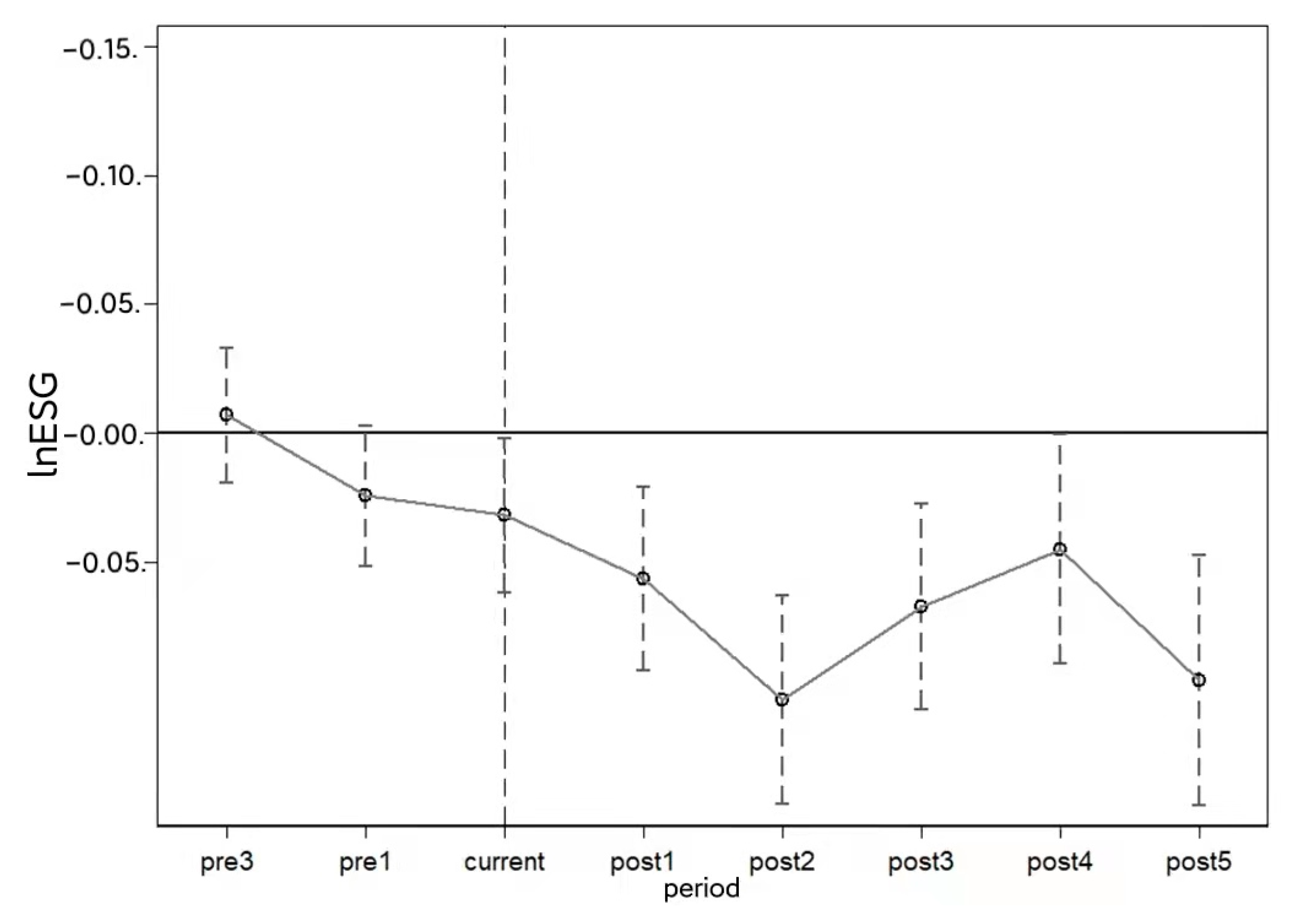

4.2. Parallel Trend Test

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Sample Exclusion Method

4.3.2. Core Explanatory Variable Substitution Method

5. Further Analysis

5.1. The Impact of Piloting on Corporate ESG Performance Based on Regional Differences

5.2. The Impact of Piloting on Corporate ESG Performance Based on Differences in Corporate Ownership

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- The government should analyze the policy impacts of AANR implementation on micro enterprises and feed the results back to the relevant government departments. In the process of promoting the implementation of the system, the government should strengthen support for enterprises. This measure could mitigate the decline in corporate ESG performance produced by factors such as higher environmental management costs.

- (2)

- Relevant government departments need to improve their enforcement of AANR and further implement and improve AANR. The system should also be rationalized based on differences in property rights. The government should strengthen its support for non-state enterprises to reduce the negative impacts of the implementation of the system on the ESG of relevant enterprises and narrow the ESG performance gap between state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises in the implementation of the exit audit system. This measures would help obviate the disadvantages of AANR.

- (3)

- Environmental management costs vary from region to region. Therefore, there is a need for differentiated AANR standards in different regions. Companies in regions with high economic levels, rapid technological development, and developed support systems in China have a strong corporate capacity to cope with changes in the external environment. Over time, these areas could raise the standard of environmental regulation. Conversely, for regions with low economic levels, slow development of science and technology, and less-developed support systems, the standard could be lowered accordingly, enabling progress to be gradual and progressive. In this way, the differences in ESG performance between Eastern and Midwestern companies in the implementation of AANR could be reduced.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, T.; Xiao, X.; Dai, Q. Transportation Infrastructure Construction and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of High-Speed Railway Opening in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Cao, X. Greening the career incentive structure for local officials in China: Does less pollution increase the chances of promotion for Chinese local leaders? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 107, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ke, Y.; Li, H.; Song, Y. Does the promotion pressure on local officials matter for regional carbon emissions? Evidence based on provincial-level leaders in China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 2881–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Cao, Q.; Tan, X.; Li, L. The effect of audit of outgoing leading officials’ natural resource accountability on environmental governance: Evidence from China. Manag. Audit. J. 2020, 35, 1213–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Pekovic, S. Corporate sustainable innovation and employee behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 1071–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, B.; Comstock, M.; Polk, D. ESG reports and ratings: What they are, why they matter. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. 27 July 2017. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2017/07/27/esg-reports-and-ratings-what-they-are-why-they-matter (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Wang, L.; Kong, D.; Zhang, J. Does the political promotion of local officials impede corporate innovation? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Chao, L. Overview of the Symposium on Exit Audit of Natural Resource Assets. Audit. Res. 2014, 4, 58–62. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=SJYZ201404012&DbName=CJFQ2014 (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Li, Z.; Liu, D. The Function Mechanism and Paths of Accountability Audit of Natural Resource Assets to Promote Ecological Civilization Construction. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Financial Management and Economic Transition (FMET 2021), Guangzhou, China, 27–29 August 2021; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Liu, W.J.; Xie, B.S. Leading officials’ accountability audit of natural resources political connection and the cost of equity capital. Audit. Res. 2018, 2, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, L. Local government environmental regulatory pressures and corporate environmental strategies: Evidence from natural resource accountability audits in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3060–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: Theory and empirical evidence. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, A.; Diab, A. The impact of social, environmental and corporate governance disclosures on firm value: Evidence from Egypt. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Hinze, A.K.; Hardeck, I. Impact of ESG factors on firm risk in Europe. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 86, 867–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruna, M.G.; Loprevite, S.; Raucci, D.; Ricca, B.; Rupo, D. Investigating the marginal impact of ESG results on corporate financial performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Petit, A. Every little helps? ESG news and stock market reaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, Y.; Li, X.; Càmara-Turull, X. Exploring the impact of sustainability (ESG) disclosure on firm value and financial performance (FP) in airline industry: The moderating role of size and age. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5052–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G. The relevance of environmental disclosures: Are such disclosures incrementally informative? J. Account. Public Policy 2013, 32, 410–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbeck, G.; Gorman, R.F. The relationship between the environmental and financial performance of public utilities. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2004, 29, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Managi, S.; Matousek, R.; Tzeremes, N.G. Does doing “good” always translate into doing “well”? An eco-efficiency perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1199–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Javakhadze, D. Corporate social responsibility and capital allocation efficiency. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 43, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Z. Stock market liberalization and corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, A.P.; García-Sánchez, I.M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. Labour practice, decent work and human rights performance and reporting: The impact of women managers. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y. MBA CEOs and corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Pagano, M.; Panizza, U. Local crowding-out in China. J. Financ. 2020, 75, 2855–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Nguyen, T.; Phan, T. Government environmental regulation, corporate social responsibility, ecosystem innovation strategy and sustainable development of Vietnamese seafood enterprises. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2021, 5, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xue, X.; Xue, W. Proactive corporate environmental responsibility and financial performance: Evidence from Chinese energy enterprises. Sustainability 2018, 10, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lan, X. How environmental regulations affect corporate innovation? The coupling mechanism of mandatory rules and voluntary management. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Z. Industry and Regional Environmental Regulations: Policy Heterogeneity and Firm Performance. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 2665–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Székely, F.; Knirsch, M. Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility: Metrics for sustainable performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China State Council. Provisions on the Leading officials’ Accountability Audit of Natural Resources (for Trial Implementation). 2017. Available online: http://www.jieyang.gov.cn/sjj/flfg/content/post_669314.html (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Wahba, H. Exploring the moderating effect of financial performance on the relationship between corporate environmental responsibility and institutional investors: Some Egyptian evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, C. Corporate governance, social responsibility information disclosure, and enterprise value in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waagstein, P.R. The mandatory corporate social responsibility in Indonesia: Problems and implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogenis, B. The valuation relevance of environmental performance revisited: The moderating role of environmental provisions. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.L.; Lins, K.V. Ownership Structure, Corporate Governance, and Firm Value: Evidence from the East Asian Financial Crisis. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 1445–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cui, J. Low-carbon city and enterprise green technology innovation. China Ind. Econ. 2020, 12, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, P.; Kacperczyk, M. Do investors care about carbon risk? J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 517–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonenc, H.; Scholtens, B. Environmental and financial performance of fossil fuel firms: A closer inspection of their interaction. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Goodell, J.W.; Shen, D. ESG rating and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Kang, Y.Y.; Huang, S.M.; Hsiao, C.Y. The Impact of ESG Performance on Business Performance before and after the COVID-19-Taking the Chinese Listed Companies as a Sample. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2022, 22, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fu, X.; Fu, X. Varieties in state capitalism and corporate innovation: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chen, S. Empirical study on the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise environmental investment. Environ. Resour. Ecol. J. 2022, 6, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.L.; Song, W.; Zhu, D.Y.; Peng, X.B.; Cai, W. Evaluating China’s regional collaboration innovation capability from the innovation actors perspective—An AHP and cluster analytical approach. Technol. Soc. 2013, 35, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimatusadiah, E.; Sofianty, D.; Ermaya, H.N. Effects of the implementation of good corporate governance on profitability. Eur. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2015, 3, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The influence of firm size on the ESG score: Corporate sustainability ratings under review. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.W.; Khan, F.A.; Shahid, A.; Ahmad, J. Effects of Debt on Value of a Firm. J. Account. Mark. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Wei, Y.; Wan, R. Leading officials’ accountability audit of natural resources and haze pollution: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, S. Accountability audit of natural resource, air pollution reduction and political promotion in China: Empirical evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.K.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Galbraith, A.A. Women’s affordability, access, and preventive care after the Affordable Care Act. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, P. Expanding employment discrimination protections for individuals with disabilities: Evidence from California. ILR Rev. 2018, 71, 365–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitler, M.P.; Gelbach, J.B.; Hoynes, H.W. Welfare reform and health. J. Hum. Resour. 2005, 40, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Lindley, M.C.; Tsai, Y.; Zhou, F. School Mandate and Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among Prekindergartners in New York City, 2012–2019. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.B.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, L.Y. Accountability audit of natural resource and air pollution control: Harmony tournament or environmental protection qualification tournament. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 10, 23–41. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=GGYY201910003&DbName=CJFQ2019 (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Ren, X.S.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhao, G.H. The impact and transmission mechanism of economic agglomeration on carbon intensity. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 95–106. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZGRZ202004011&DbName=CJFQ2020 (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X. How does environmental regulation moderate the relationship between foreign direct investment and marine green economy efficiency: An empirical evidence from China’s coastal areas. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 219, 106077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. Industrial spatial selection effects of environmental regulation and regional strategic adjustment. Dongyue Trib. 2021, 42, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhou, H. Environmental regulation and firm technological innovation: An empirical study based on heterogeneous competitive strategies. Enterp. Econ. 2022, 41, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Y. Ownership type, technological innovation and firm performance. China Soft Sci. 2015, 3, 28–40. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZGRK201503004&DbName=CJFQ2015 (accessed on 21 August 2022).

| Three Aspects | 14 Themes | 26 Key Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Environmental Management System | Environmental Management System |

| Green Management Objectives | A low-carbon plan or goal | |

| Green Management Plan | ||

| Green Products | Carbon Footprint | |

| Sustainable products or services | ||

| External Environmental Certification | Product or company receives environmental certification | |

| Environmental violations | Environmental violations | |

| Social | Institutional System | Social Responsibility Report |

| Health and Safety | Goals or plans to reduce safety incidents | |

| Negative business events | ||

| Trends in operating accidents | ||

| Social Contribution | Social Responsibility Related Donations | |

| Employee growth rate | ||

| Countryside Revitalization | ||

| Quality Management | Product or company receives quality certification | |

| Governance | System Building | Corporate self-ESG monitoring |

| Governance Structure | Connected Transactions | |

| Board Independence | ||

| Operating Risk | Overall financial credibility | |

| Asset Quality | ||

| Short-term debt service risk | ||

| Equity Pledge Risk | ||

| Quality of Information Disclosure | ||

| External Discipline | Violations of laws and regulations by listed companies and subsidiaries | |

| Violations by executives and shareholders | ||

| Business Activities | Tax Transparency |

| Variables | Variables Explanation | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate ESG Performance | ESG performance is categorized into “C-AAA” grades with a score of “1–9”, respectively | Data from the Sino-Securities ESG Index scoring system in the WIND database |

| Audit Pilot | If the company is registered in the pilot area, take 1, otherwise take 0; If the company is established after the start of the pilot take 1, otherwise take 0; The final variable value is the product of these two items | Pilot information from the “China Audit Yearbook” and the official website of the provincial and municipal audit bureaus; Company information from WIND database |

| Top 10 shareholders’ shareholding ratio | The top 10 shareholders’ shareholdings ratio to the total number of shares | Data from WIND database |

| Return on assets | The ratio of a firm’s net interest rate to its total assets | Data from WIND database |

| Loan of Asset Ratio | Ratio of total liabilities at the end of the period to total assets at the end of the period | Data from WIND database |

| Accounts receivable turnover ratio | Primary business’s revenue ratio to average accounts receivable | Data from WIND database |

| Firm size | The natural logarithm of total assets | Data from WIND database |

| regional innovation level | Total utility value of China’s regional innovation capacity | Data from comes the China Regional Innovation Capacity Evaluation Report |

| Variables | Symbols | Observations | Average | Standard Deviation | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate ESG Performance | lnESG | 8892 | 1.325 | 0.350 | 0.000 | 2.079 |

| Audit Pilot | TREAT*POST | 8892 | 0.212 | 0.409 | 0 | 1 |

| Top 10 shareholders’ shareholding ratio | lnTOPIC10 | 8892 | 0.439 | 0.100 | 0.086 | 0.669 |

| Return on assets | lnROA | 8892 | 0.711 | 0.027 | 0.626 | 0.776 |

| Loan of Asset Ratio | lnLEV | 8892 | 0.353 | 0.145 | 0.071 | 0.623 |

| Accounts receivable turnover ratio | lnART | 8892 | 2.319 | 1.225 | 0.747 | 5.991 |

| Firm size | lnSIZE | 8892 | 12.940 | 1.285 | 5.731 | 18.480 |

| regional innovation level | lnINNOV | 8892 | 3.565 | 0.364 | 2.759 | 4.087 |

| Average | (1) Mixed OLS | (2) RE | (3) FE | (4) FE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TREAT × POST | −0.056 *** (−5.88) | −0.066 *** (−4.66) | −0.055 *** (−3.77) | −0.058 *** (−3.73) |

| lnTOPIC10 | 0.023 (0.64) | 0.131 ** (2.19) | — | 0.187 ** (2.37) |

| lnROA | 1.448 *** (8.51) | 0.853 *** (4.52) | — | 0.643 *** (3.25) |

| lnLEV | −0.422 *** (−13.51) | −0.344 *** (−7.06) | — | −0.306 *** (−4.98) |

| lnART | 0.005 (1.63) | 0.015 *** (3.17) | — | 0.021 *** (2.71) |

| lnSIZE | 0.079 *** (24.56) | 0.053 *** (8.34) | — | 0.033 *** (3.46) |

| lnINNOV | 0.061 *** (5.54) | 0.082 *** (3.66) | — | 0.144 ** (2.44) |

| Constant term | −0.803 *** (−6.51) | −0.222 (−1.27) | 1.337 *** (432.60) | −0.081 (−0.28) |

| R-squared | 0.117 | — | 0.004 | 0.027 |

| Corporate fixed effects | — | — | YES | YES |

| Observations | 8892 | 8892 | 8892 | 8892 |

| Number of companies | 988 | 988 | 988 | 988 |

| Variables | (5) FE | (6) FE | (7) FE | (8) FE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TREAT × POST | −0.073 *** (−2.67) | −0.077 *** (−2.62) | — | — |

| lnER | — | — | −0.110 * (−1.82) | −0.111 * (−1.89) |

| Constant term | 1.320 *** (353.10) | 0.165 (0.34) | 1.367 *** (43.85) | 0.257 (0.53) |

| Control variables | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| R-squared | 0.004 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.016 |

| Corporate fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 4237 | 4237 | 4203 | 4203 |

| Number of companies | 524 | 524 | 519 | 519 |

| Variables | (9) Eastern Region | (10) Central Region | (11) Western Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| TREAT × POST | −0.042 ** (−2.47) | −0.122 *** (−2.98) | −0.084 * (−1.90) |

| Constant term | −0.118 (−0.30) | −0.965 * (−1.70) | 0.772 (1.39) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.030 | 0.039 | 0.025 |

| Corporate fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 5373 | 1854 | 1665 |

| Number of companies | 597 | 206 | 185 |

| Variables | (12) Non-State Enterprises | (13) State-Owned Enterprises |

|---|---|---|

| TREAT × POST | −0.073 *** (−3.63) | −0.022 (−0.98) |

| Constant term | −0.301 (−0.74) | 0.028 (0.07) |

| Control variables | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.038 | 0.020 |

| Observations | 5310 | 3582 |

| Number of companies | 627 | 445 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Huang, M.; Lin, Q.; Lin, W. Government Environmental Regulation and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Natural Resource Accountability Audits in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010447

Yan Y, Cheng Q, Huang M, Lin Q, Lin W. Government Environmental Regulation and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Natural Resource Accountability Audits in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010447

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Yingzheng, Qiuwang Cheng, Menglan Huang, Qiaohua Lin, and Wenhe Lin. 2023. "Government Environmental Regulation and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Natural Resource Accountability Audits in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010447

APA StyleYan, Y., Cheng, Q., Huang, M., Lin, Q., & Lin, W. (2023). Government Environmental Regulation and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Natural Resource Accountability Audits in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010447