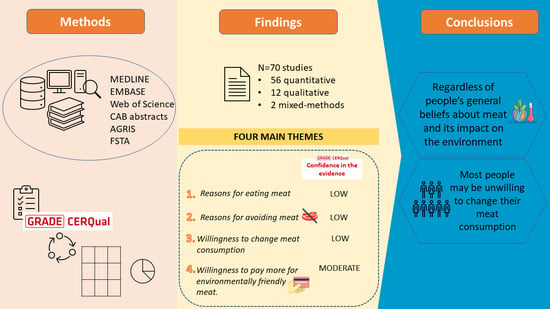

People’s Values and Preferences about Meat Consumption in View of the Potential Environmental Impacts of Meat: A Mixed-methods Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk-of-Bias/Methodological Limitations Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

- Type of data: whether the findings were from quantitative (e.g., questionnaire) or qualitative (e.g., interview) data sets.

- Previous knowledge/information on the environmental impact of meat: whether the participants had been informed about the environmental impact of meat before being asked about their beliefs, preferences, and/or behaviours.

2.6. Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses

2.7. Confidence in the Evidence

3. Results

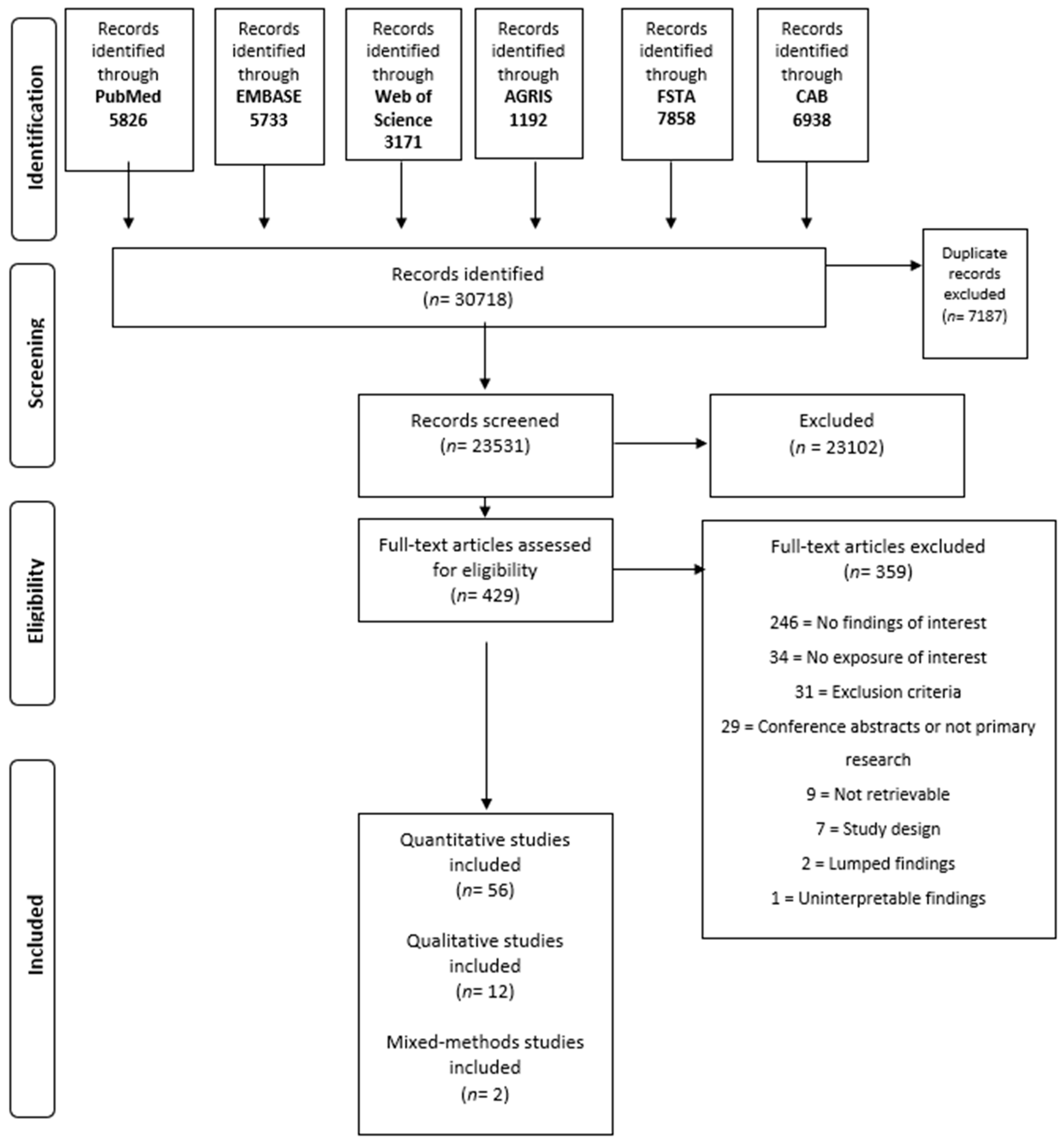

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

4. Findings

4.1. Reasons for Eating and/or Buying Meat

4.1.1. Quantitative Data Set

Informing about the Environmental Impact

Not Informing about the Environmental Impact

4.1.2. Qualitative Data Set

4.1.3. Integrated Evidence and Related Confidence

4.2. Reasons for Avoiding Meat

4.2.1. Quantitative Data Set

4.2.2. Qualitative Data Set

4.2.3. Integrated Evidence and Related Confidence

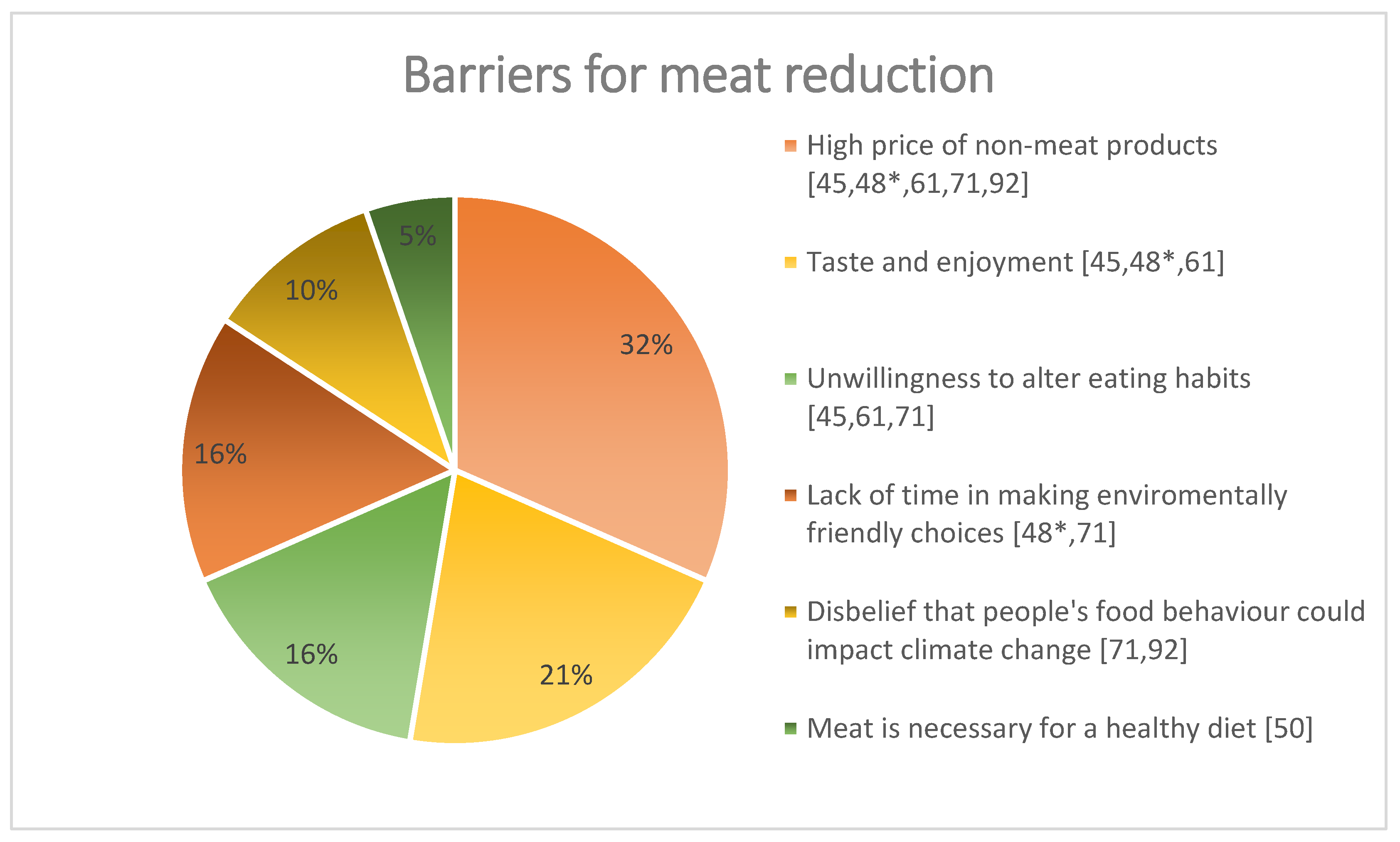

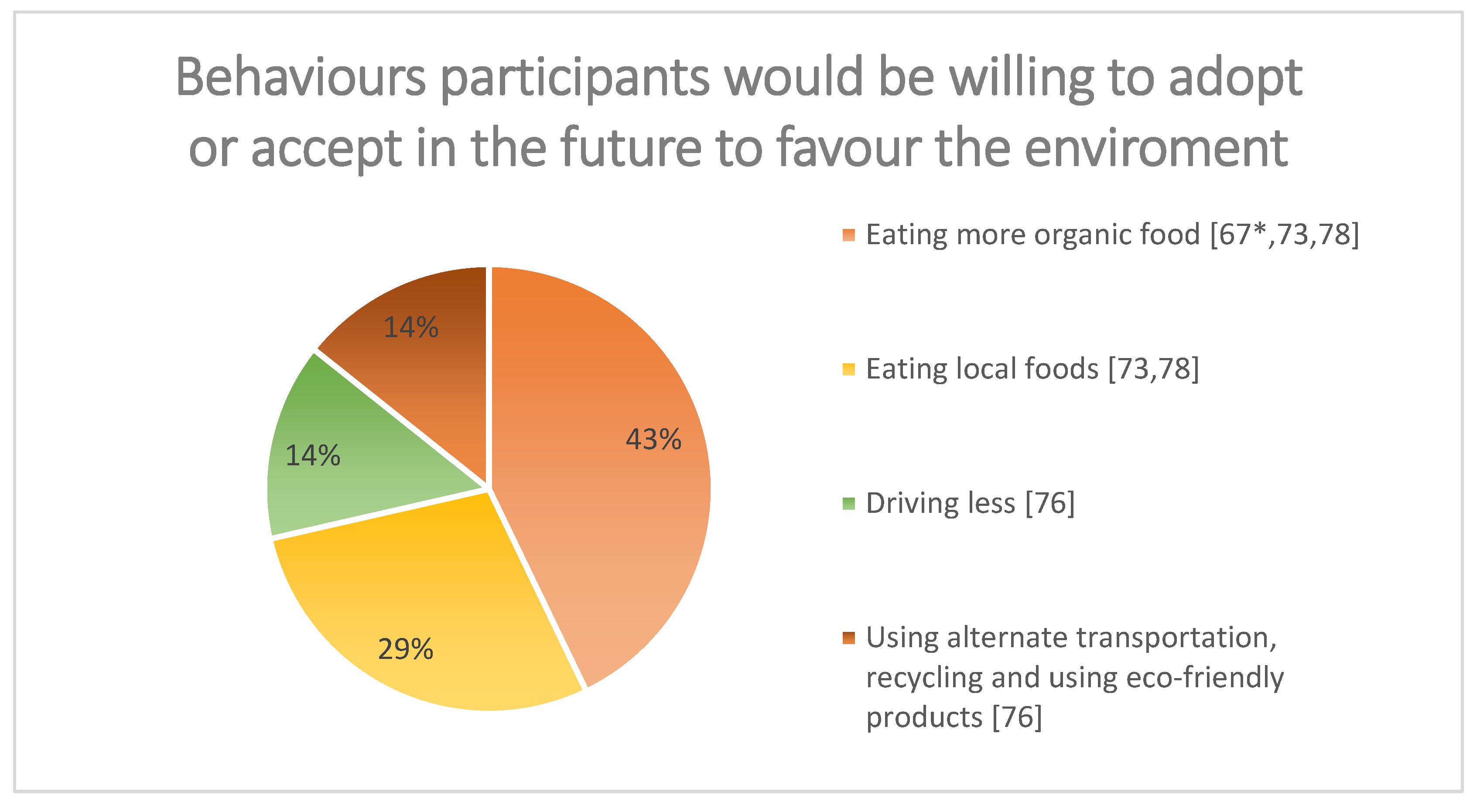

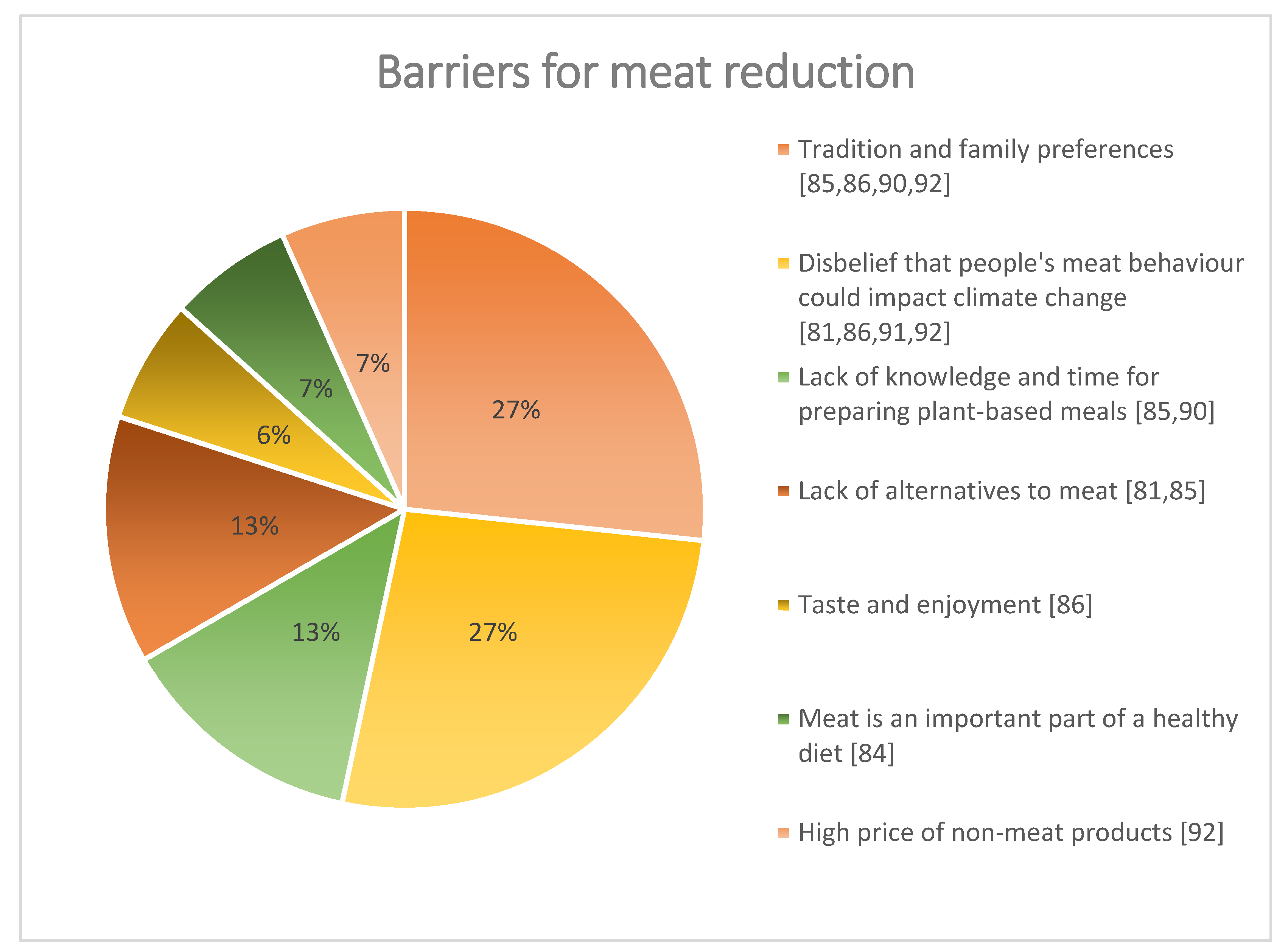

4.3. Willingness to Change Meat Consumption

4.3.1. Quantitative Data Set

Informing about the Environmental Impact

Not Informing about the Environmental Impact

4.3.2. Qualitative Data Set

Informing about the Environmental Impact

Not Informing about the Environmental Impact

4.3.3. Integrated Evidence and Related Confidence

4.4. Willingness to Pay More for Environmentally Friendly Meat

Quantitative Data Set

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

5.3. Our Results in the Context of Previous Research

5.4. Implications for Research and Practice

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGRIS | International System for Agricultural Science and Technology |

| CAB abstracts | Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience |

| CERQual | Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| CMNS | critical meta-narrative synthesis |

| FSTA | Food Science and Technology Abstracts |

| ML | methodological limitations |

| NutriRECS | Nutritional Recommendations and accessible Evidence summaries Composed of Systematic reviews |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RoB | risk of bias |

References

- Caso, G.; Vecchio, R. Factors influencing independent older adults (un)healthy food choices: A systematic review and research agenda. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Food Choice and Nutrition: A Social Psychological Perspective. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8712–8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valli, C.; Rabassa, M.; Johnston, B.C.; Kuijpers, R.; Prokop-Dorner, A.; Zajac, J.; Storman, D.; Storman, M.; Bala, M.M.; Solà, I.; et al. Health-Related Values and Preferences Regarding Meat Consumption: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Considering how farm animal welfare concerns may contribute to more sustainable diets. Appetite 2022, 168, 105786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, C.; Stover, P.J.; Ohlhorst, S.D.; Field, M.S.; Steinbrook, R.; Rowe, S.; Woteki, C.; Campbell, E. Best practices in nutrition science to earn and keep the public’s trust. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedios, M.C.; Esperato, A.; De-Regil, L.M.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Norris, S.L. Improving the adaptability of WHO evidence-informed guidelines for nutrition actions: Results of a mixed methods evaluation. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabassa, M.; Ruiz, S.G.-R.; Solà, I.; Pardo-Hernandez, H.; Alonso-Coello, P.; García, L.M. Nutrition guidelines vary widely in methodological quality: An overview of reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 104, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabassa, M.; Ponce, Y.H.; Garcia-Ribera, S.; Johnston, B.C.; Castell, G.S.; Manera, M.; Rodrigo, C.P.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Martínez-González, M.; Alonso-Coello, P. Food-based dietary guidelines in Spain: An assessment of their methodological quality. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.C.; Zeraatkar, D.; Han, M.A.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Valli, C.; El Dib, R.; Marshall, C.; Stover, P.J.; Fairweather-Taitt, S.; Wójcik, G.; et al. Unprocessed Red Meat and Processed Meat Consumption: Dietary Guideline Recommendations From the Nutritional Recommendations (NutriRECS) Consortium. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.D.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2006; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/a0701e/a0701e.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Bouwman, L.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Van Der Hoek, K.W.; Beusen, A.H.W.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Willems, J.; Rufino, M.C.; Stehfest, E. Exploring global changes in nitrogen and phosphorus cycles in agriculture induced by livestock production over the 1900–2050 period. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20882–20887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvergne, P. The Shadows of Consumption: Consequences for the Global Environment; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 0-262-26057-3. Available online: http://mitp-content-server.mit.edu:18180/books/content/sectbyfn?collid=books_pres_0id=7706fn=9780262514927_sch_0001.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Valli, C.; Rabassa, M.; Zera, D.; Prokop-Dorner, A.; Zajac, J.; Swierz, M.; Storman, D.; Storman, M.; Król, A.; Jasińska, A.; et al. Adults’ Beliefs, Preferences and Attitudes about Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review Protocol. PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018088854. 2018. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018088854 (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Alonso Coello, P.; Guyatt, G.H.; Yepes-Nuñez, J.J.; Akl, E.A.; Hazlewood, G.; Pardo-Hernandez, H.; Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I.; Qaseem, A.; Williams Jr, J.W.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 19. Assessing the certainty of evidence in the importance of outcomes or values and preferences—Risk of bias and indirectness. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Qualitative) Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Karimi, M.; Clark, A.M. How do patients’ values influence heart failure self-care decision-making?: A mixed-methods systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 59, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M.; Voils, C.I.; Barroso, J. Defining and Designing Mixed Research Synthesis Studies. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Bujold, M.; Wassef, M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: Implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs-Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Results in Health Science Mixed Methods Research Through Joint Displays. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, A.; Pedersen, M.; Durante, A. Characteristics of joint displays illustrating data integration in mixed-methods nursing studies. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 76, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S.; Bohren, M.; Rashidian, A.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Glenton, C.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—Paper 2: How to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, C.; Mcleay, F. To meat or not to meat? Comparing empowered meat consumers’ and anti-consumers’ preferences for sustainability labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, A.; Mesias, F.J.; Escribano, M. Consumer Assessment of Sustainability Traits in Meat Production. A Choice Experiment Study in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L.J.; Kole, A.; Van de Kroon, S.M.A.; de Lauwere, C. Consumer Attitudes Towards the Development of Animal-Friendly Husbandry Systems. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic 2005, 18, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.; Sonntag, W.; Glanz-Chanos, V.; Forum, S. Consumer interest in environmental impact, safety, health and animal welfare aspects of modern pig production: Results of a cross-national choice experiment. Meat Sci. 2018, 137, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koistinen, L.; Pouta, E.; Heikkilä, J.; Forsman-Hugg, S.; Kotro, J.; Mäkelä, J.; Niva, M. The impact of fat content, production methods and carbon footprint information on consumer preferences for minced meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 29, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.; de Boer, M.; O’Reilly, S.; Cotter, L. Factors influencing intention to purchase beef in the Irish market. Meat Sci. 2003, 65, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.; O’Reilly, S.; Cotter, L.; de Boer, M. Factors influencing consumption of pork and poultry in the Irish market. Appetite 2004, 43, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péneau, S.; Fassier, P.; Allès, B.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Hercberg, S.; Méjean, C. Dilemma between health and environmental motives when purchasing animal food products: Sociodemographic and nutritional characteristics of consumers. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, A.; Nitzko, S.; Spiller, A. Consumer Response to Negative Information on Meat Consumption in Germany. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic, A. Studying social aspects of vegetarianism: A research proposal on the basis of a survey among adult population of two Slovenian biggest cities. Coll. Antropol. 2013, 37, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar]

- De Backer, C.J.; Hudders, L. From Meatless Mondays to Meatless Sundays: Motivations for Meat Reduction among Vegetarians and Semi-vegetarians Who Mildly or Significantly Reduce Their Meat Intake. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gavelle, E.; Davidenko, O.; Fouillet, H.; Delarue, J.; Darcel, N.; Huneau, J.F.; Mariotti, F. Self-declared attitudes and beliefs regarding protein sources are a good prediction of the degree of transition to a low-meat diet in France. Appetite 2019, 142, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyett, P.A.; Sabaté, J.; Haddad, E.; Rajaram, S.; Shavlik, D. Vegan lifestyle behaviors. An exploration of congruence with health-related beliefs and assessed health indices. Appetite 2013, 67, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagmann, D.; Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Meat avoidance: Motives, alternative proteins and diet quality in a sample of Swiss consumers. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2448–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverstock, K.; Forgays, D.K. To eat or not to eat. A comparison of current and former animal product limiters. Appetite 2012, 58, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A.; Golden, L.L. Moral Emotions and Social Activism: The Case of Animal Rights. J. Soc. Issues 2009, 65, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.R.; Stallings, S.F.; Bessinger, R.C.; Brooks, G. Differences between health and ethical vegetarians. Strength of conviction, nutrition knowledge, dietary restriction, and duration of adherence. Appetite 2013, 65, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Chen, S. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmirli, S.; Phillips, C.J. The relationship between student consumption of animal products and attitudes to animals in Europe and Asia. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, M.; Nitzko, S.; Spiller, A. Analysis of Differences in Meat Consumption Patterns. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A. Benefits and barriers to the consumption of a vegetarian diet in Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2003, 6, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A. What proportion of South Australian adult non-vegetarians hold similar beliefs to vegetarians? Nutr. Diet. 2004, 61, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Lentz, G.; Connelly, S.; Mirosa, M.; Jowett, T. Gauging attitudes and behaviours: Meat consumption and potential reduction. Appetite 2018, 127, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeman, M.; Sirelius, M. Food choice ideologies: The modern manifestations of normative and humanist views of the world. Appetite 2001, 37, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullee, A.; Vermeire, L.; Vanaelst, B.; Mullie, P.; Deriemaeker, P.; Leenaert, T.; De Henauw, S.; Dunne, A.; Gunter, M.J.; Clarys, P.; et al. Vegetarianism and meat consumption: A comparison of attitudes and beliefs between vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous subjects in Belgium. Appetite 2017, 114, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, R.A.; Edwards, D.; Palmer, A.; Ramsing, R.; Righter, A.; Wolfson, J. Reducing meat consumption in the USA: A nationally representative survey of attitudes and behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C.; Izmirli, S.; Aldavood, J.; Alonso, M.; Choe, B.; Hanlon, A.; Handziska, A.; Illmann, G.; Keeling, L.; Kennedy, M.; et al. An International Comparison of Female and Male Students’ Attitudes to the Use of Animals. Animals 2011, 1, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploll, U.; Stern, T. From diet to behaviour: Exploring environmental- and animal-conscious behaviour among Austrian vegetarians and vegans. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3249–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, R.; Wellens, B.; Conner, M. Attitudes towards following meat, vegetarian and vegan diets: An examination of the role of ambivalence. Appetite 2001, 37, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribis, P.; Pencak, R.C.; Grajales, T. Beliefs and Attitudes toward Vegetarian Lifestyle across Generations. Nutrients 2010, 2, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.B.; Heine, S.J.; Kamble, S.; Cheng, T.K.; Waddar, M. Compassion and contamination. Cultural differences in vegetarianism. Appetite 2013, 71, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schösler, H.; de Boer, J.; Boersema, J.J.; Aiking, H. Meat and masculinity among young Chinese, Turkish and Dutch adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2015, 89, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Impact of sustainability perception on consumption of organic meat and meat substitutes. Appetite 2019, 132, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, E.H.; Elon, L.K.; Frank, E. Personal and Professional Correlates of US Medical Students’ Vegetarianism. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Sustainable food consumption. Product choice or curtailment? Appetite 2015, 91, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asvatourian, V.; Craig, T.; Horgan, G.; Kyle, J.; Macdiarmid, J. Relationship between pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour and dietary intake patterns. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.J. We Can’t Keep Meating Like This: Attitudes towards Vegetarian and Vegan Diets in the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clonan, A.; Wilson, P.; Swift, J.A.; Leibovici, D.G.; Holdsworth, M. Red and processed meat consumption and purchasing behaviours and attitudes: Impacts for human health, animal welfare and environmental sustainability. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2446–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Boersema, J.J. Climate change and meat eating: An inconvenient couple? J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; de Witt, A.; Aiking, H. Help the climate, change your diet: A cross-sectional study on how to involve consumers in a transition to a low-carbon society. Appetite 2016, 98, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Prospects for pro-environmental protein consumption in Europe: Cultural, culinary, economic and psychological factors. Appetite 2018, 121, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groeve, B.; Bleys, B. Less Meat Initiatives at Ghent University: Assessing the Support among Students and How to Increase It. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginn, J.; Lickel, B. A Motivated Defense of Meat: Biased Perceptions of Meat’s Environmental Impact. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 76, 12362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.; Röös, E. Fear of climate change consequences and predictors of intentions to alter meat consumption. Food Policy 2016, 62, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvala, T.; Niva, M.; Mäkelä, J.; Pouta, E.; Heikkilä, J.; Kotro, J.; Forsman-Hugg, S. Diversifying meat consumption patterns: Consumers’ self-reported past behaviour and intentions for change. Meat Sci. 2012, 92, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A. Australian consumers’ food-related environmental beliefs and behaviours. Appetite 2008, 50, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkiniemi, J.-P.; Vainio, A. Barriers to climate-friendly food choices among young adults in Finland. Appetite 2014, 74, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; Goddard, E. Committed vs. uncommitted meat eaters: Understanding willingness to change protein consumption. Appetite 2019, 138, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjolainen, P.; Tapio, P.; Vinnari, M.; Jokinen, P.; Räsänen, P. Consumer consciousness on meat and the environment—Exploring differences. Appetite 2016, 101, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaichi, F.; Revoredo Giha, C.; Glenk, K.; Gil, J.M. How Consumers in the UK and Spain Value the Coexistence of the Claims Low Fat, Local, Organic and Low Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Nutrients 2020, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite 2011, 57, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truelove, H.B.; Parks, C. Perceptions of behaviors that cause and mitigate global warming and intentions to perform these behaviors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Van Loo, E.J.; Gellynck, X.; Verbeke, W. Flemish consumer attitudes towards more sustainable food choices. Appetite 2013, 62, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, M.; Visschers, V.; Hartmann, C. Factors influencing changes in sustainability perception of various food behaviors: Results of a longitudinal study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 46, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J.E. Becoming Vegetarian: The Eating Patterns and Accounts of Newly Practicing Vegetarians. Food Foodways 2011, 19, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.; Ward, K. Health, ethics and environment: A qualitative study of vegetarian motivations. Appetite 2008, 50, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Moral Disengagement in Harmful but Cherished Food Practices? An Exploration into the Case of Meat. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic 2014, 27, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, K. Where’s the Beef? (With Vegans): A Qualitative Study of Vegan-Omnivore Conflict. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Happer, C.; Wellesley, L. Meat consumption, behaviour and the media environment: A focus group analysis across four countries. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Pearson, D.; James, S.W.; Lawrence, M.A.; Friel, S. Shrinking the food-print: A qualitative study into consumer perceptions, experiences and attitudes towards healthy and environmentally friendly food behaviours. Appetite 2017, 108, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A.; Crawford, D. Australian Adult Consumers’ Beliefs About Plant Foods: A Qualitative Study. Health Educ. Behav. 2005, 32, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdiarmid, J.I.; Douglas, F.; Campbell, J. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: Public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite 2016, 96, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEachern, M.G.; Schröder, M.J.A. The Role of Livestock Production Ethics in Consumer Values Towards Meat. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic 2002, 15, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycek, M. Meatless meals and masculinity: How veg* men explain their plant-based diets. Food Foodw. 2018, 26, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylan, J. Sustainable Consumption in Everyday Life: A Qualitative Study of UK Consumer Experiences of Meat Reduction. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendrup, S.; Röös, E.; Schütt, E. Evaluating ConsumerUnderstanding of the Swedish Meat Guide—A Multi-layered Environmental Information Tool Communicating Trade-offs When Choosing Food. Environ. Commun. 2017, 13, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austgulen, M.H.; Skuland, S.E.; Schjøll, A.; Alfnes, F. Consumer Readiness to Reduce Meat Consumption for the Purpose of Environmental Sustainability: Insights from Norway. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.; Kallis, G.; Zografos, C. Why environmentalists eat meat. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Badilla-Briones, Y.; Sabaté, J. Understanding Attitudes towards Reducing Meat Consumption for Environmental Reasons. A Qualitative Synthesis Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer Attitudes Towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Id * | Primary Focus | Country | Type of Study | Data Collection Methods | Sampling | Included Participants | Gender (% Female) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akaichi 2020 [74] | To investigate substitution and complementary effects of beef mince attributes (with a focus on labels of Low, Moderate, High Fat, Local, National, Imported, Organic, Low, Moderate, and High Greenhouse Gas Emissions) on consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay for the product, drawing on data from large choice experiments conducted in the UK and Spain. | UK and Spain | QUANT | Questionnaire | Quota | 2417 | 60 |

| Apostolidis 2019 [25] | To compare and contrast the importance of the seven sustainability-related labels for three consumer groups (meat eaters, meat reducers, and vegetarians). | UK | QUANT | Questionnaire administered face to face | Convenience | 600 | 65 |

| Asvatourian 2018 [60] | To identify dietary patterns and their associated GHG emissions, then to explore their relationship, as domain-specific behavioural patterns, with measures of environmental attitudes and behaviours. | South West Scotland | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Random | 422 | 32 |

| Bryant 2019 [61] | To investigate UK meat-eaters’ views of various aspects of vegetarianism and veganism. | United Kingdom | QUANT | Questionnaire | Convenience | 1000 | 50 |

| Clonan 2015 [62] | To investigate consumers’ self-reported red and processed meat consumption (from intake and purchasing data) against/towards animal welfare, human health, and environmental sustainability. | UK | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Random | 842 | 60 |

| Cordts 2014 [33] | To determine the effect of information regarding the negative attributes of meat consumption on demand for meat in Germany, with the focus on four particular attributes: animal welfare, human health, personal image, and climate change. | Germany | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Quota | 590 | 48 |

| Crnic 2013 [34] | To investigate the fundamental characteristics of vegetarianism. | Slovenia | QUANT | Questionnaire | Random | NR | NR |

| de Boer 2013 [63] | To investigate consumers’ behaviours towards meat consumption and climate change. | Netherlands | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Stratified | 1083 | 50 |

| de Boer 2016 [64] | To assess how consumers evaluate the mitigation effectiveness of the food-related and the energy-related options, particularly whether they recognise the crucial differences between the less meat option, the local food option, and the organic food option. | Netherlands | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Quota | 527 | 50 |

| de Boer 2018 [65] | To assess how responses to the options for pro-environmental protein consumption (plant based or animal based) might be shaped by cultural, culinary, and economic spatial gradients (including GDP per capita) at the regional level and differences in environmentally friendly behaviour and gender at the individual level. | EU countries (Portugal; Spain; Malta; Slovenia; Greece; Cyprus; Hungary; Bulgaria; Romania; Latvia; Lithuania; Estonia; Poland; Slovakia; Czech Republic; Italy; France; Ireland; United Kingdom; Netherlands; Belgium; Luxembourg; Germany; Austria; Finland; Sweden; Denmark) | QUANT | Telephone survey | Random | 24340 | NR |

| de Gavelle 2019 [36] | To identify different dietary types which might constitute degrees of transition to low-meat diets (omnivores, pro-flexitarians, flexitarians, vegetarians), to characterise how these diets differ in terms of protein source intake, and to determine whether attitudes and beliefs might explain these dietary types. | France | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Quota | 2055 | 52 |

| De Groeve 2017 [66] | To examine associations between the support and variables related to meat curtailment and to examine the effect of providing information about the climate impact of meat on the support for the less meat initiatives (LMIs). | Belgium | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 429 | 54 |

| DeBacker 2014 [35] | To investigate the motives underlying the different forms of vegetarianism and semi-vegetarianism in a culture where meat continues to play a crucial role in people’s diets. | Flanders, Belgium | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 1556 | NR |

| Dyett 2013 [37] | To explore the main reasons for adopting and maintaining a vegan lifestyle among a heterogenous group of vegans from different U.S. states; and to determine whether participants’ diet and lifestyle choices coincided with positive health indices and selected outcome assessment. | USA | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Convenience | 100 | 76 |

| Eldesouky 2020 [26] | To obtain information on the consumer decision-making process for beef, in order to determine the relative importance of sustainability claims and traditional attributes, and to identify consumer profiles with similar perceptions and intentions. | Spain | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Random stratified | 285 | 51 |

| Frewer 2005 [27] | To investigate consumers’ perceptions and attitudes towards animal welfare issues related to animal husbandry and environmental impact. | Netherlands | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 1000 | NR |

| Ginn 2019 (Study 1) [67] | To examine perceived effectiveness of meat reduction as a climate change mitigation strategy. | United States | QUANT | Questionnaire | Convenience | 527 | 60 |

| Ginn 2019 (Study 2) [67] | To examine whether people responded differently to brief messages about meat’s impact than to messages about more traditionally accepted strategies for mitigating climate change (e.g., driving less). | United States | QUANT | Questionnaire | Convenience | 275 | 52 |

| Grunert 2018 [28] | First, to analyse which production attributes related to environment, health, and animal welfare are ranked highest by consumers when making choices about purchases of pork in Germany and Poland. Second, to investigate how those production attributes that are regarded as important by consumers are traded off against conventional product attributes (fat content, colour, origin) and price in a choice experiment. | Germany; Poland | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 2005 | 48 |

| Hagmann 2019 [38] | To compare consumer groups with different self-declared diet styles regarding meat (vegetarians/vegans, pescatarians, low- and regular meat consumers) in terms of their motives, protein consumption, diet quality, and weight status. | Switzerland | QUANT | Paper-based questionnaire | Random | 4213 | 47 |

| Haverstock 2012 [39] | To examine participants’ reasons for limiting animal products as well as factors related to stability or disruption of participant animal product limitation. To focus on differences and similarities between current and former animal product limiters (pescatarians, vegetarians, vegans). | USA | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Snowball and convenience | 247 | 85 |

| Herzog 2009 [40] | To examine the relationships between a moral emotion (i.e., sensitivity to visceral disgust) and animal activism, attitudes toward animal welfare, and consumption of meat. | USA | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 424 | 67 |

| Hoffman 2013 [41] | To examine the differences between health-oriented and ethical-oriented vegetarians by comparing conviction, nutrition knowledge, dietary restriction, and years as vegetarian between the two groups. | USA | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 312 | 85 |

| Hopwood 2020 [42] | To evaluate the structure of common motives for a vegetarian diet, to use that measure to develop behavioural and psychological profiles of people who would be most likely to adopt a plant-based diet for different reasons, and to examine whether this profile predicts responses to advocacy materials. | United States | QUANT | Questionnaire | Convenience | 7488 | 57 |

| Hunter 2016 [68] | To explore fear using protection motivation theory to measure how individuals appraise and cope with the threat of climate change consequences in the food mitigation context in order to understand factors which motivate consumers to reduce or alter their meat consumption. | Sweden | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Random | 219 | 45 |

| Izmirli 2011 [43] | To determine the relationship between the consumption of animal products and attitudes towards animals among university students in Eurasia. | 11 Eurasian countries: China, Czech Republic, Great Britain, Iran, Ireland, South Korea, Macedonia, Norway, Serbia, Spain, and Sweden | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 3.433 | NR |

| Kayser 2013 [44] | To analyse the determinants that play a role in the differences in meat consumption patterns in Germany. | Germany | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Quota | 956 | 51 |

| Koistinen 2013 [29] | To provide information on the relative preferences of consumers for minced meat attributes and examine whether meat type, method of production, fat content, price, and presence of carbon footprint information have impact on consumer choice. | Finland | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Purposive | 1.623 | 50 |

| Latvala 2012 [69] | To examine changes in meat consumption among Finnish consumers, taking into account both stated past changes and intended future changes. Reasons for change were also identified. | Finland | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Purposive | 1623 | 50 |

| Lea 2003 [45] | The aim of this study was to examine consumers’ perceived benefits and barriers to the consumption of a vegetarian diet. | South Australia | QUANT | Questionnaire | Random | 601 | 57 |

| Lea 2004 [46] | To determine the proportion of non-vegetarians with similar beliefs as vegetarians and to examine their personal characteristics. | Australia | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Partly random and partly nonrandom | 707 | 56 |

| Lea 2008 [70] | To examine Australians’ food-related environmental beliefs and behaviours. | Australia | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Random | 223 | 52 |

| Lentz 2018 [47] | To explore the understanding of meat consumption and potential drivers for its reduction in New Zealand. The study investigated consumers’ attitudes, motivations, and behaviours in regard to meat consumption. | New Zealand | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Random | 841 | 50 |

| Lindeman 2001 (Study 1) [48] | To examine whether abstract values are related to concrete Food Choice Motives (FCMs), whether these Food Choice Ideologies (FCIs) are related to a humanist or a normative view of the world, and whether various dietary groups (e.g., vegetarians and omnivores) endorse these FCIs in different ways. | Finland | QUANT | Paper-based questionnaire | Convenience | 82 | 100 |

| Lindeman 2001 (Study 2) [48] | To examine whether abstract values are related to concrete Food Choice Motives (FCMs), whether these Food Choice Ideologies (FCIs) are related to a humanist or a normative view of the world, and whether various dietary groups (e.g., vegetarians and omnivores) endorse these FCIs in different ways. | Finland | QUANT | Paper-based questionnaire | Convenience | 149 | 100 |

| Mäkiniemi 2014 [71] | To examine how young adults in Finland perceive barriers to climate-friendly food choices and how these barriers are associated with their choices. | Finland | QUANT | Paper-based questionnaire | Convenience | 350 | 80 |

| Malek 2019 [72] | To identify consumer segments with varying levels of willingness to make the following changes to their protein consumption: reduce meat consumption, follow a meat-free diet most of the time, avoid meat consumption altogether, and follow a strict plant-based diet (i.e., stop eating all animal products). | Australia | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Panel provider/quota sampling? | 287 | 53 |

| McCarthy 2003 [30] | To examine consumer perceptions towards beef and the influence of these perceptions on consumption. | Ireland | QUANT | Questionnaire | Random | 218 | NR |

| McCarthy 2004 [31] | To investigate Irish consumers’ beliefs about pork and poultry consumption. | Ireland | QUANT | Questionnaire on a ‘door to door’ basis | Random | 257 | 87 |

| Mullee 2017 [49] | To investigate the attitudes and beliefs about vegetarianism and meat consumption among the Belgian population to better understand motivations underlying these behaviours. | Belgium | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Random | 2.436 | 49 |

| Neff 2017 [50] | To learn about what is eaten in meatless meals and attitudes and perceptions towards meat reduction, and to build upon and add depth to previous research on meat-reduction behaviours in the USA and other high-meat-consuming countries. | USA | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 1112 | 51 |

| Peneau 2017 [32] | To investigate the sociodemographic profiles of individuals reporting health and environmental dilemmas when purchasing meat, fish, and dairy products, and to compare diet quality of individuals with and without dilemmas. | France | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 22,935 | 75 |

| Philips 2011 [51] | To examine whether social dominance differences between countries influence attitudes towards the use of animals, by surveying the student population in a range of Eurasian countries. | 11 Eurasian countries: China, Czech Republic, Great Britain, Iran, Ireland, South Korea, Macedonia, Norway, Serbia, Spain, and Sweden | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience and random | 3432 | 55 |

| Ploll 2019 [52] | To provide insights into the relationship between motives and the expression of behavioural patterns of vegetarians and vegans in comparison to the average omnivore. | Austria | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire and hard copy in person | Convenience | 556 | 80 |

| Pohjolainen 2016 [73] | To analyse consumer environmental consciousness, including problem awareness and support to action dimensions, the latter including perceived self-efficacy as well as solutions to problems. | Finland | QUANT | Questionnaire | Random | 1890 | 56 |

| Povey 2001 [53] | To examine differences between the attitudes and beliefs of four dietary groups (meat eaters, meat avoiders, vegetarians, and vegans) and the extent to which attitudes influence intentions to follow each diet. Additionally, the role of ambivalence was examined. | United Kingdom | QUANT | Questionnaire | Convenience | 111 | 40 |

| Pribis 2010 [54] | To examine whether reasons to adopt vegetarian lifestyle differ significantly among generations. | USA | QUANT | Questionnaire | Convenience | 609 | 65 |

| Ruby 2013 (Study 1) [55] | To explore vegetarians concerns about the impact of their daily food choices on the environment and on animal suffering. | NR | QUANT | Questionnaire | Convenience | 272 | 65 |

| Schösler 2015 [56] | To investigate whether the alleged link between meat consumption and particular framings of masculinity, which emphasise that ‘real men’ eat meat, may stand in the way of achieving objectives. To analyse whether meat-related gender differences vary across ethnic groups (Turkish, Chinese, and Native Dutch). | Netherlands | QUANT | Questionnaire administered face to face | Quota and snowball | 1057 | 52 |

| Siegrist 2015 [57] | To examine whether the perceptions of various environment-related food consumption patterns changed between 2010 and 2014 and what factors influenced such changes. | Switzerland | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Random | 2781 | 54 |

| Siegrist 2019 [78] | To examine how consumers evaluated the environmental impact of various foods, and to investigate whether the perceived environmental effect of foods, health consciousness, and food disgust sensitivity is related to the consumption of meat substitutes and organic meat. | Switzerland | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Random | 5586 | 52 |

| Spencer 2007 [58] | To examine dietary and other personal health characteristics, as well as mentoring and clinical characteristics, for association with US medical students’ vegetarianism. | USA | QUANT | Paper-based questionnaire | Convenience | 1849 | NR |

| Tobler 2011 [75] | To examine consumers’ beliefs about ecological food consumption and their willingness to adopt such behaviours. | Switzerland | QUANT | Postal survey questionnaire | Random | 6189 | 52 |

| Truelove 2012 [76] | To explore people’s perceptions and attitudes of behaviour that cause and mitigate global warming. | USA | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 112 | 61 |

| Vanhonacker 2013 [77] | To explore consumer attitudes towards a series of food choices with a lower ecological impact. | Belgium | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Convenience | 221 | 64 |

| Verain 2015 [59] | To explore different types of sustainable food behaviours. A distinction between sustainable product choices and curtailment behaviour is empirically investigated and predictors of the two types of behaviours are identified. | Netherlands | QUANT | Online survey questionnaire | Quota | 942 | 50 |

| Boyle 2011 [79] | To investigate the eating patterns and vocabularies of motives for newly practicing, or developmental, vegetarians. | US | QUAL | Semi-structured interviews | Snowball | 45 | 100 |

| Fox 2008 [80] | To examine, by means of online ethnographic methods, vegetarians’ own perspectives on how health, ethical, and environmental beliefs motivate their food choices; to investigate the interactions between beliefs on health, animal cruelty, and the environment, and how these may contribute to food choice trajectory. | US, UK, Canada | QUAL | Interviews | Convenience | 33 | 70 |

| Graça 2014 [81] | To contribute to a further understanding of the psychological factors that may hinder or promote a personal disposition to change food habits to benefit each of these domains, and to explore people’s opinions about how different lifestyles and behaviours affect the environment, public health, and animals. | Portugal | QUAL | Semi-structured focus groups | Convenience | 40 | 63 |

| Guerin 2014 [82] | To investigate interpersonal interactions and conflicts between vegans and omnivores. | US | QUAL | Interviews | Snowball | 19 | 53 |

| Happer 2019 [83] | To uncover the way in which attitudes and behavioural commitments might be negotiated in response to new information and through interaction with others. | China, Brazil, UK, US | QUAL | Focus groups | Quota | 270 | NR |

| Hoek 2016 [84] | To investigate consumers’ perceptions, experiences, and attitudes toward health and environmental aspects in relation to foods. | Australia | QUAL | Semi-structured, virtual, face-to-face interviews | Quota | 29 | 56 |

| Lea 2005 [85] | To investigate consumers’ perceived barriers and benefits of plant food consumption and views on the promotion of these foods. | Australia | QUAL | Focus groups | Convenience | 50 | 72 |

| Macdiarmid 2016 [86] | To explore in depth the public’s view and perception of the environmental impact of food and awareness of the link between climate change and meat, and to gauge the public’s opinion about their willingness to eat less meat as part of a more sustainable diet. | Scotland | QUAL | Focus groups | Purposive | 87 | 54 |

| Mceachern 2002 [87] | To investigate consumer value residing in meat consumption, with special emphasis on factors relating to organic production values. | Scotland | QUAL | Semi-structured, in-depth interviews | Quota sampling and snowballing | 30 | 100 |

| Myceck 2018 [88] | To understand how vegans and vegetarians conceptualise and explain their food consumption identities in relation to their broader identity practices. | US | QUAL | In-depth, face-to-face interviews | Purposive and snowballing | 20 | 0 |

| Mylan 2018 [89] | To understand how meat consumers enact ‘meat reduction’ in the context of their everyday lives, exploring the motivations, strategies, and experiences of eating less meat. | UK | QUAL | Semi-structured interviews | Convenience | 20 | NR |

| Spendrup 2017 [90] | To gain an understanding of consumers’ arguments in making a conscious consumer choice of protein and the strategies used for reaching such a purchase decision. | Sweden | QUAL | Focus groups | Purposive | 21 | NR |

| Austgulen 2018 [91] | To investigate whether Norwegian consumers are ready to make food choices based on what is environmentally sustainable. | Norway | MM | Online questionnaire and focus groups | Quota | 1532 | 50 |

| Scott 2019 [92] | To investigate how people reason and explain their apparently unsustainable actions given their environmental beliefs and how people that one would think were more prone to being vegetarian justify their choice to eat meat. | Spain | MM | Face-to-face survey questionnaire | Convenience | 42 | 43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valli, C.; Maraj, M.; Prokop-Dorner, A.; Kaloteraki, C.; Steiner, C.; Rabassa, M.; Solà, I.; Zajac, J.; Johnston, B.C.; Guyatt, G.H.; et al. People’s Values and Preferences about Meat Consumption in View of the Potential Environmental Impacts of Meat: A Mixed-methods Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010286

Valli C, Maraj M, Prokop-Dorner A, Kaloteraki C, Steiner C, Rabassa M, Solà I, Zajac J, Johnston BC, Guyatt GH, et al. People’s Values and Preferences about Meat Consumption in View of the Potential Environmental Impacts of Meat: A Mixed-methods Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010286

Chicago/Turabian StyleValli, Claudia, Małgorzata Maraj, Anna Prokop-Dorner, Chrysoula Kaloteraki, Corinna Steiner, Montserrat Rabassa, Ivan Solà, Joanna Zajac, Bradley C. Johnston, Gordon H. Guyatt, and et al. 2023. "People’s Values and Preferences about Meat Consumption in View of the Potential Environmental Impacts of Meat: A Mixed-methods Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010286

APA StyleValli, C., Maraj, M., Prokop-Dorner, A., Kaloteraki, C., Steiner, C., Rabassa, M., Solà, I., Zajac, J., Johnston, B. C., Guyatt, G. H., Bala, M. M., & Alonso-Coello, P. (2023). People’s Values and Preferences about Meat Consumption in View of the Potential Environmental Impacts of Meat: A Mixed-methods Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010286