The Coach–Athlete–Parent Relationship: The Importance of the Sex, Sport Type, and Family Composition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Overview of PNPCAP Items, Subscales, and MANOVA Results

3.2. Group Analysis Statistics for the Positive and Negative PNPCAP Subscale

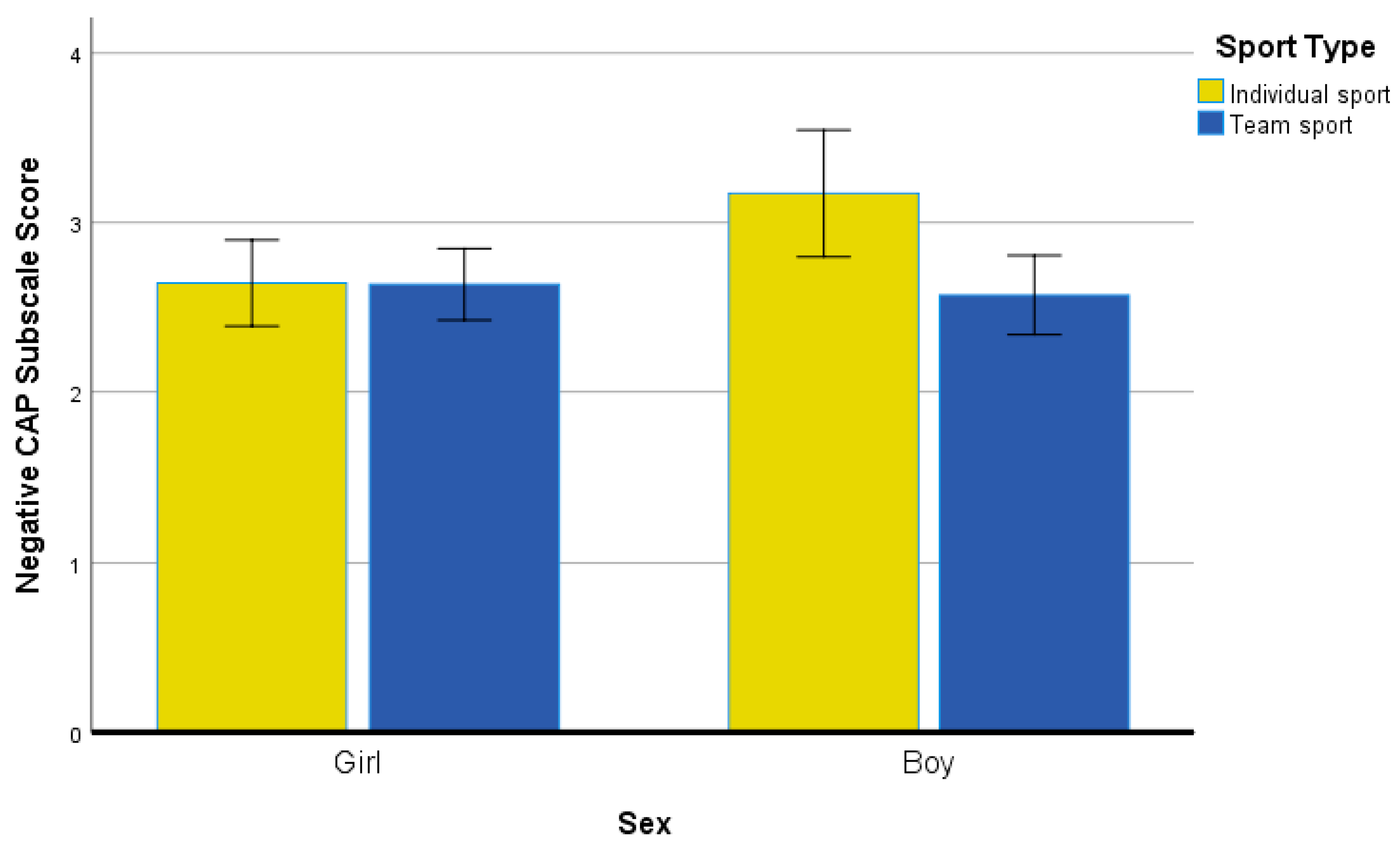

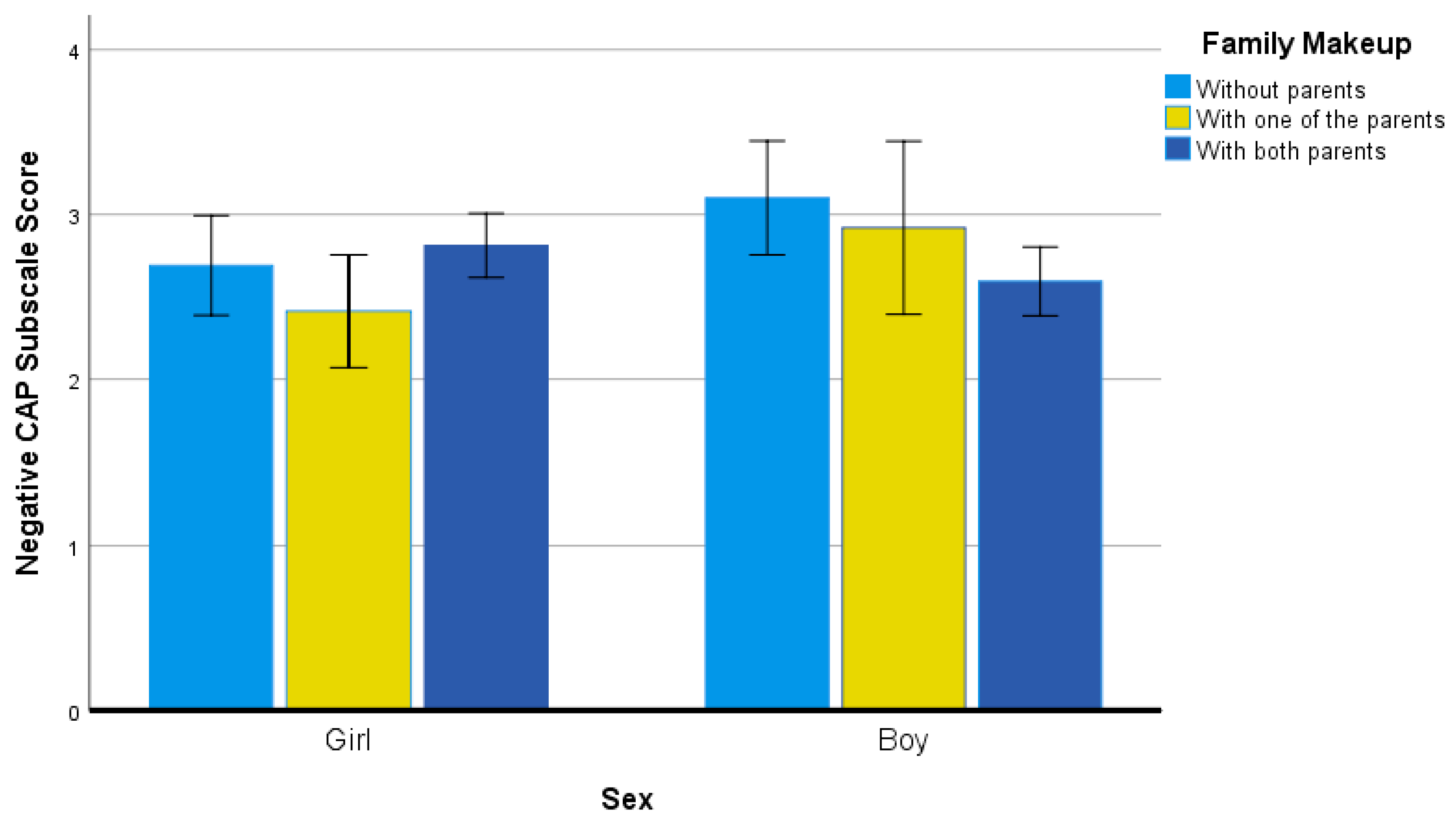

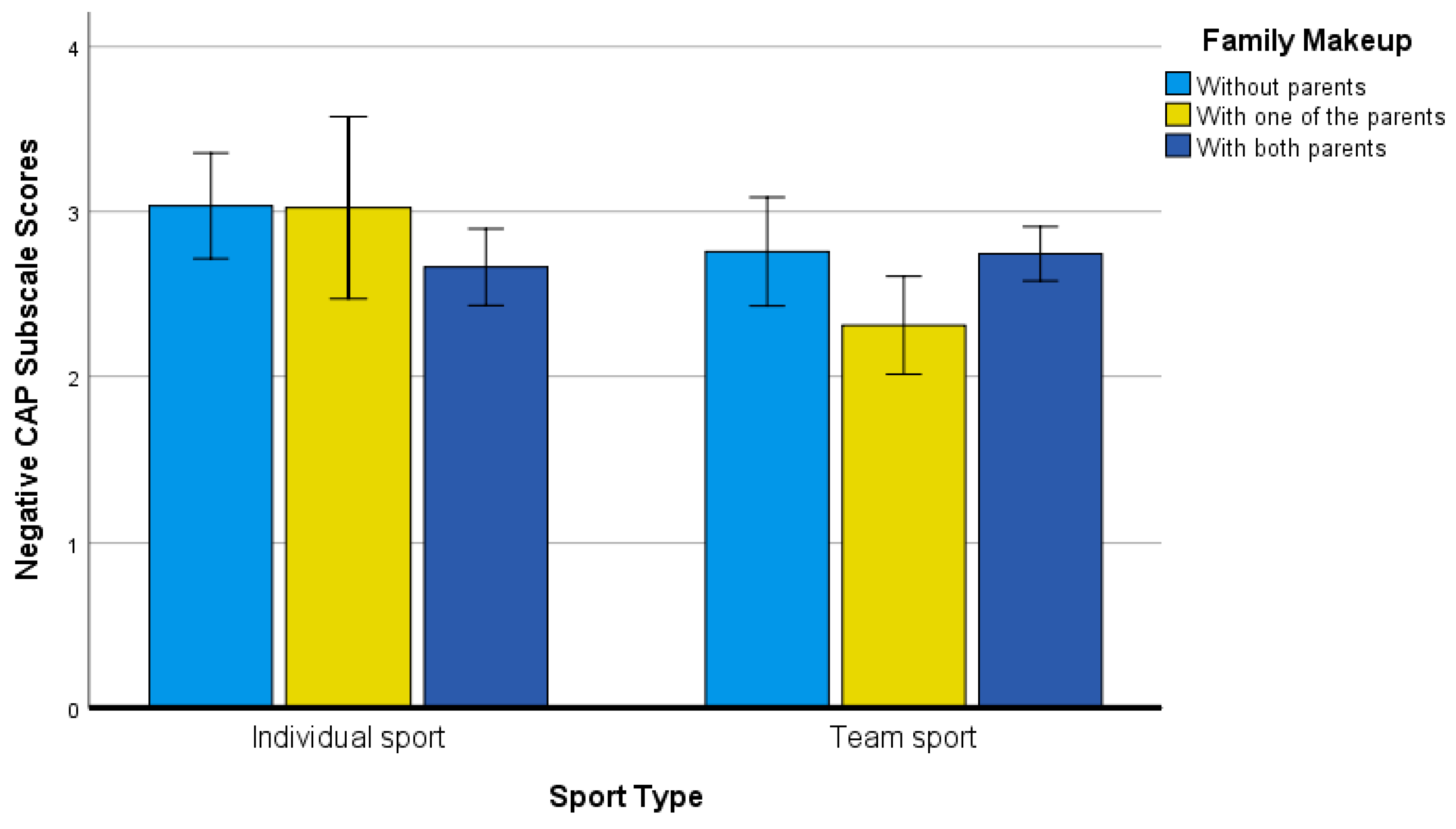

3.3. Group Interactions for the Negative PNPCAP Subscale

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Ideas for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lisinskiene, A.; Lochbaum, M.; May, E.; Huml, M. Quantifying the Coach–Athlete–Parent (C–A–P) Relationship in Youth Sport: Initial Development of the Positive and Negative Processes in the C–A–P Questionnaire (PNPCAP). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisinskiene, A.; May, E.; Lochbaum, M. The Initial Questionnaire Development in Measuring of Coach-Athlete–Parent Interpersonal Relationships: Results of Two Qualitative Investigations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camiré, M.; Trudel, P.; Forneris, T. Coaching and Transferring Life Skills: Philosophies and Strategies Used by Model High School Coaches. Sports Psychol. 2012, 26, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortín, F.J.; Maestre, M.; Garcia de Alcaraz, A. Formación a entrenadores de fútbol base y grado de satisfacción de los deportistas. SPORT TK-Rev. EuroAm. Cienc. Deporte 2016, 5, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, P.R.; Ntoumanis, N.; Quested, E.; Viladrich, C.; Duda, J.I. Initial validation of the coach-created Empowering and Disempowering Motivational Climate Questionnaire (EDMCQ-C). Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.; Gray, S.; Sproule, J. The microstructure of coaching practice: Behaviors and activities of an elite rugby union head coach during preparation and competition. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 34, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M. Exploring biographical learning in elite soccer coaching. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Practical Sports Coaching; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Lisinskiene, A. Educational Interaction between Adolescents and Parents in Sporting Activities. Ph.D. Dissertation, LSU, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, N.L.; Knight, C. Parenting in Youth Sport: From Research to Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukadinović, S.; Rađević, N. The coach-athlete relationship of young talented athletes from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Fiz. Kult. 2019, 73, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.D. Adolescence, 10th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Lavallee, D.; Sheridan, D.; Coffee, P.; Daly, P. A Social Support Intervention to Reduce Intentions to Drop-out from Youth Sport: The GAA Super Games Centre. Psychosoc. Interv. 2019, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, L.; Jowett, S. Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Attachment, Need Satisfaction, and Well-Being in a Sample of Athletes: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2017, 11, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Black, D.E. Parenting styles and specific parenting strategies in youth sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 170. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, C.J.; Holt, N.L. Parenting in youth sport: Understanding and enhancing children’s experiences. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 15, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Poczwardowski, A. Understanding the Coach-Athlete Relationship. In Social Psychology in Sport; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S. Attachment in Sport, Exercise, and Wellness; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S. Adolescent–parent attachment characteristics and quality of youth sport friendship. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L. Positive Youth Development through Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, N.L.; Knight, C.J. Sport Participation. In Book Encyclopedia of Adolescence, 1st ed.; Brown, B.B., Prinstein, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gleaves, T.; Lang, M. Kicking “No-Touch” Discourses into Touch: Athletes’ Parents’ Constructions of Appropriate Coach–Child Athlete Physical Contact. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2017, 41, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, T.E.; Smith, A.L.; McDonough, M.H. Parents’ perceptions of child-to-parent socialization in organized youth sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 31, 444–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsch, T.E.; Smith, A.L.; Wilson, S.R.; McDonough, M.H. Parent goals and verbal sideline behavior in organized youth sport. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2015, 4, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, D.; Lauer, L.; Rolo, C.; Jannes, C.; Pennisi, N. The Role of Parents in Tennis Success: Focus Group Interviews with Junior Coaches. Sport Psychol. 2008, 22, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthner, P.; Trudel, P. A New Theoretical Perspective for Understanding How Coaches Learn to Coach. Sport Psychol. 2006, 20, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, C.G.; Caglar, E.; Thrower, S.N.; Smith, J.M.J. Development and Validation of the Parent-Initiated Motivational Climate in Individual Sport Competition Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Pol, P.K.C.; Kavussanu, M.; Ring, C. Goal orientations, perceived motivational climate, and motivational outcomes in football: A comparison between training and competition contexts. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Pol, P.K.C.; Kavussanu, M. Achievement goals and motivational responses in tennis: Does the context matter? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lisinskiene, A.; Guetterman, T.; Sukys, S. Understanding Adolescent–Parent Interpersonal Relationships in Youth Sports: A Mixed-Methods Study. Sports 2018, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisinskiene, A.; Lochbaum, M. A Qualitative study examining parental involvement in youth sports over a one-year intervention program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turman, P.D. Parental Sport Involvement: Parental influence to encourage young athlete continued sport participation. J. Fam. Commun. 2007, 7, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.J.; Holt, N.L. Parenting in youth tennis: Understanding and enhancing children’s experiences. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Stoner, E.; Hefner, T.; Cooper, S.; Lane, A.M.; Terry, P.C. Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, E.; Dobersek, U.; Gershgoren, L.; Becker, B.; Tenenbaum, G. The cohesion–performance relationship in sport: A 10-year retrospective meta-analysis. Sport Sci. Health 2014, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Zanatta, T.; Kirschling, D.; May, E. The profile of moods states and athletic performance: A meta-analysis of published studies. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Zanatta, T.; Kazak, Z. The 2 × 2 achievement goals in sport and physical activity contexts: A meta-analytic test of context, gender, culture, and socioeconomic status differences and analysis of motivations, regulations, affect, effort, and physical activity correlates. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 173–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisinskiene, A.; Huml, M.; Lochbaum, M. Discriminant validity of the positive and negative processes in the C–A–P Questionnaire. J. Human Sport Exer. 2022, 17, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, C.G.; Keegan, R.J.; Smith, J.M.J.; Raine, A.S. A systematic review of the intrapersonal correlates of motivational climate perceptions in sport and physical activity. Psychol. Sport Exer. 2015, 18, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 95% LL | 95% UL | Min | Max | Kurtosis | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: Reliable during hardship | 3.94 | 0.98 | 3.86 | 4.01 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.39 | −0.87 |

| Q2: Are a team | 4.00 | 0.89 | 3.93 | 4.06 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.77 | −0.83 |

| Q3: Is positive | 4.04 | 0.81 | 3.98 | 4.11 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.29 | −0.89 |

| Q4: Works together | 3.94 | 0.90 | 3.87 | 4.01 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.59 | −0.80 |

| Q5: Mutual respect | 4.06 | 0.83 | 4.00 | 4.12 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.10 | −0.90 |

| Q6: Is supportive | 4.10 | 0.76 | 4.04 | 4.16 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.08 | −0.77 |

| Q7: Listens to each other | 3.99 | 0.85 | 3.93 | 4.06 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.67 | −0.75 |

| Q8: Expects too much | 2.62 | 1.10 | 2.53 | 2.71 | 1.00 | 5.00 | −0.63 | 0.26 |

| Q9: Oversteps boundaries | 2.54 | 1.13 | 2.45 | 2.62 | 1.00 | 5.00 | −0.57 | 0.42 |

| Q10: Too demanding | 2.86 | 1.19 | 2.76 | 2.95 | 1.00 | 5.00 | −1.01 | 0.07 |

| Q11: Over involved | 2.82 | 1.17 | 2.73 | 2.91 | 1.00 | 5.00 | −0.80 | 0.16 |

| Positive CAP subscale | 4.01 | 0.63 | 3.96 | 4.06 | 2.00 | 5.00 | −0.32 | −0.25 |

| Negative CAP subscale | 2.71 | 0.92 | 2.64 | 2.78 | 1.00 | 5.00 | −0.46 | 0.11 |

| Categorical Variable | Groups | n | M | SE | 95% CI | Difference Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | Univariate F | p | η2 | |||||

| Sex | Girl | 343 | 4.01 | 0.03 | 3.94 | 4.08 | |||

| Boy | 289 | 4.01 | 0.04 | 3.93 | 4.08 | F(1, 631) = 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.00 | |

| Sport type | Individual | 313 | 4.04 | 0.04 | 3.97 | 4.11 | |||

| Team sport | 319 | 3.97 | 0.04 | 3.91 | 4.04 | F(1, 631) = 1.94 | 0.17 | 0.00 | |

| Family Makeup | No parents | 70 | 4.11 | 0.08 | 3.96 | 4.26 | |||

| One parent | 57 | 3.93 | 0.09 | 3.76 | 4.10 | ||||

| Both parents | 199 | 3.95 | 0.05 | 3.86 | 4.04 | F(2, 323) = 1.81 | 0.17 | 0.01 | |

| Age group | 11–13 yrs. | 220 | 3.97 | 0.04 | 3.88 | 4.05 | |||

| 14–16 yrs. | 255 | 4.00 | 0.04 | 3.92 | 4.07 | ||||

| 17–19 yrs. | 157 | 4.09 | 0.05 | 3.99 | 4.19 | F(2, 629) = 1.88 | 0.15 | 0.01 | |

| Sport experience | 2–3 yrs. | 216 | 3.95 | 0.04 | 3.86 | 4.03 | |||

| 3–4 yrs. | 163 | 4.00 | 0.05 | 3.90 | 4.10 | ||||

| 5–6+ yrs. | 253 | 4.07 | 0.04 | 3.99 | 4.14 | F(2, 629) = 2.05 | 0.13 | 0.01 | |

| 95% CI | Difference Statistics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical Variable | Groups | n | M | SE | LL | UL | Univariate F | p | η2 |

| Sex | Girl | 343 | 2.70 | 0.05 | 2.60 | 2.80 | |||

| Boy | 289 | 2.72 | 0.05 | 2.61 | 2.82 | F(1, 631) = 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.00 | |

| Sport type | Individual | 313 | 2.78 | 0.05 | 2.68 | 2.88 | |||

| Team sport | 319 | 2.64 | 0.05 | 2.53 | 2.74 | F(1, 631) = 4.13 | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Family makeup | Both parents | 199 | 3.95 | 0.05 | 3.86 | 4.04 | |||

| No parents | 70 | 2.85 | 0.12 | 2.62 | 3.08 | ||||

| One parent | 57 | 2.43 | 0.13 | 2.18 | 2.69 | ||||

| Both parents | 199 | 2.72 | 0.07 | 2.59 | 2.86 | F(2, 323) = 2.98 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Age group | 11–13 yrs. | 220 | 2.63 | 0.06 | 2.51 | 2.75 | |||

| 14–16 yrs. | 255 | 2.74 | 0.06 | 2.63 | 2.86 | ||||

| 17–19 yrs. | 157 | 2.76 | 0.07 | 2.61 | 2.90 | F(2, 629) = 1.18 | 0.31 | 0.00 | |

| Sport experience | 2–3 yrs. | 216 | 2.75 | 0.06 | 2.63 | 2.87 | |||

| 3–4 yrs. | 163 | 2.78 | 0.07 | 2.64 | 2.92 | ||||

| 5–6+ yrs. | 253 | 2.63 | 0.06 | 2.51 | 2.74 | F(2, 629) = 1.72 | 0.18 | 0.01 | |

| Interaction Groups | n | M | SE | 95% CI | Difference Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | Univariate F | p | η2 | |||||

| Girl | Individual sport | 166 | 2.64 | 0.13 | 2.39 | 2.90 | |||

| Team sport | 177 | 2.64 | 0.11 | 2.42 | 2.85 | ||||

| Boy | Individual sport | 147 | 3.17 | 0.19 | 2.80 | 3.55 | |||

| Team sport | 142 | 2.57 | 0.12 | 2.34 | 2.81 | F(1, 314) = 4.47 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| Girl | Without parents | 40 | 2.69 | 0.15 | 2.39 | 2.99 | |||

| With one of the parents | 36 | 2.41 | 0.17 | 2.07 | 2.76 | ||||

| With both parents | 107 | 2.81 | 0.10 | 2.62 | 3.01 | ||||

| Boy | Without parents | 30 | 3.10 | 0.18 | 2.75 | 3.45 | |||

| With one of the parents | 21 | 2.92 | 0.27 | 2.39 | 3.45 | ||||

| With both parents | 92 | 2.59 | 0.11 | 2.39 | 2.80 | F(2, 314) = 3.89 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Individual sport | Without parents | 37 | 3.04 | 0.16 | 2.71 | 3.36 | |||

| With one of the parents | 15 | 3.02 | 0.28 | 2.47 | 3.58 | ||||

| With both parents | 66 | 2.66 | 0.12 | 2.43 | 2.90 | ||||

| Team sport | Without parents | 33 | 2.76 | 0.17 | 2.43 | 3.09 | |||

| With one of the parents | 42 | 2.31 | 0.15 | 2.01 | 2.61 | ||||

| With both parents | 133 | 2.74 | 0.08 | 2.58 | 2.91 | F(2, 314) = 2.91 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisinskiene, A.; Lochbaum, M. The Coach–Athlete–Parent Relationship: The Importance of the Sex, Sport Type, and Family Composition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084821

Lisinskiene A, Lochbaum M. The Coach–Athlete–Parent Relationship: The Importance of the Sex, Sport Type, and Family Composition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084821

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisinskiene, Ausra, and Marc Lochbaum. 2022. "The Coach–Athlete–Parent Relationship: The Importance of the Sex, Sport Type, and Family Composition" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084821

APA StyleLisinskiene, A., & Lochbaum, M. (2022). The Coach–Athlete–Parent Relationship: The Importance of the Sex, Sport Type, and Family Composition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084821