A Systematic Review of Studies Describing the Effectiveness, Acceptability, and Potential Harms of Place-Based Interventions to Address Loneliness and Mental Health Problems

Highlights

- First systematic review to investigate the impact of local spatial factors on loneliness and mental health problems.

- Seven studies were found that investigated the impact of place-based interventions on loneliness and mental health.

- Interventions involving the use of local community facilities and active engagement in green spaces show most promise.

- The review found no trials, identifying a need for formal trial evidence.

- There is a need for investment in intervention development across a wide range of place-based factors.

- Clinicians might consider including place-based interventions in care plans to address loneliness and mental health.

- Policymakers should consider the potential for community facilities and green spaces to benefit local connectedness.

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

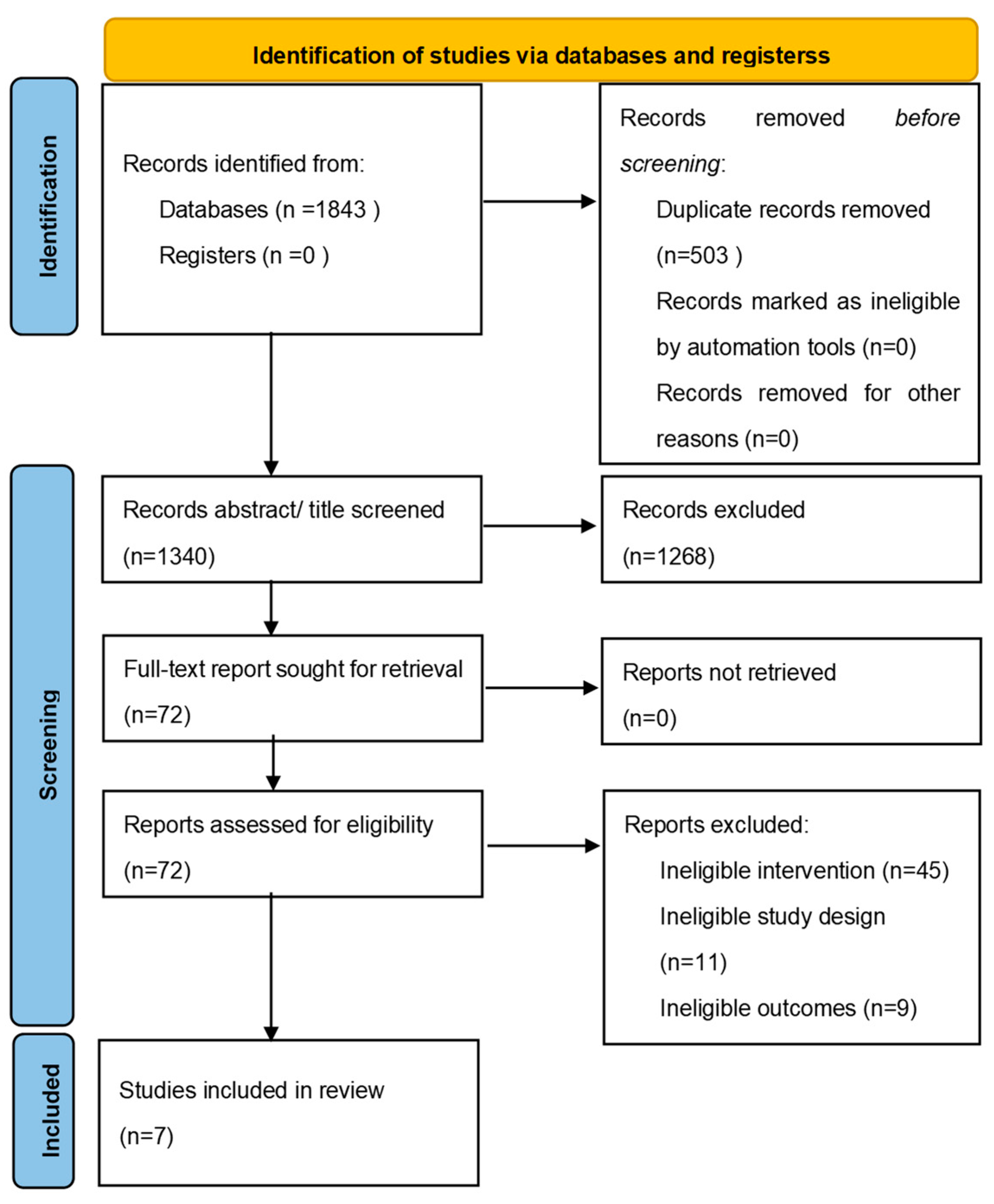

3.1. Studies Identified

3.2. Study Quality

3.3. Results of Identified Studies

3.3.1. Provision of Community Facilities

3.3.2. Active Engagement in Local Green Spaces

3.3.3. Housing Regeneration

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Findings in the Context of Other Literature

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Policy, Research and Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy

Appendix A.1. Concept: Place-Based Factors

Appendix A.2. Concept: Intervention

Appendix A.3. Concept: Loneliness

Appendix A.4. Concept: Mental Health Problems OR Suicidality

Appendix B

| Study (Author & Year) | Country/Setting | Place-Based Intervention (and Category) | Theory of Change/Likely Mechanisms | Sample Size and Characteristics (Total Size, % Female, Mean Age) | Outcome Measure(s) | Study Design/Statistical Analysis | Key Findings | Potential Harms Identified | Methodological Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of community facilities | |||||||||

| Levinger et al., 2020 [52] | Australia; Elderly participants recruited from the general community in the suburbs close to the Seniors Exercise Parks in Melbourne, between October 2018 to November 2019 | Seniors Exercise Park program: a 12-week structured supervised physical activity program using an outdoor exercise park, followed by a 6-month unstructured physical activity program (ongoing unsupervised access to the exercise park/twice a week exercise session with no formal structured group activity) Each structured exercise session was followed by morning/afternoon tea | Actively promote community wellbeing through the provision of a unique exercise and social support program in elderly people as well as the effects of sustained engagement in physical activity on physical, mental, social and health outcomes |

|

| Pre-post study design

|

| None |

|

| Wang et al., 2020 [58] | China; Elderly participants recruited from villages of Jinhua in Zhejiang, between July and October 2017 | Community canteen services offered to older adults in 7 villages, compared with older adults from 7 closest villages without canteen services. | Recipients of the canteen service (canteen group; CG) would show significantly better health than the non-recipients (NCG) | Final sample size of 284 elderly people responded to the survey comprehensively

|

|

|

| Not measured |

|

| Housing regeneration | |||||||||

| Jalaludin et al., 2012 [53] | Australia; Participants recruited from all 57 households in a suburb 45 km to the southwest of the Sydney central business district from December 2008 to April 2009 | Urban renewal program conducted between April 2009 and August 2010, and in the two streets of established social housing

| The renewal program and its social components were intended to bring about improvement in social capital, social connectedness, a sense of community and in the economic conditions of residents. |

|

| Pre-post study design

Correction but uncorrected exact p-values were presented throughout the manuscript. | Uncorrected p values presented suggested that there were no significant differences on any measures. The authors reported: no significant change in perceptions of neighbourhood aesthetics, safety or walkability, or in psychological distress and self-rated health. They reported a significant increase in the proportion of people reporting that there were attractive buildings and homes in the neighbourhood (18% versus 64%), and of feeling that they belonged to the neighbourhood (48% versus 70%), that their area had a reputation for being a safe place (8% versus 27%), they felt safe walking down their street after dark (52% versus 85%), and that people who came to live in the neighbourhood would be more likely to stay rather than move elsewhere (13% versus 54%). As the lowest uncorrected p-value presented was 0.0072, we infer that all corrected p-values showed no statistically significant findings. | None |

|

| Study (Author & Year) | Country/Setting | Place-Based Intervention (and Category) | Theory of Change/Likely Mechanisms | Sample Size and Characteristics (Total Size, % Female, Mean Age) | Study Design and Analytic Approach | Key Themes | Potential Harms Identified | Methodological Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of community facilities | ||||||||

| Carolan et al., 2011 [54] | United States; Participants recruited from a clubhouse in a rural community of a mid-western state | Clubhouse programme intended as a recovery community to foster interpersonal connections and support for individuals with mental illnesses | Based on a trans-ecological model that emphasizes the proximal relationships developed by individuals with persons and aspects of their environment | 20 people (50% female)

|

| Two overarching themes:

| None |

|

| Active engagement in local green spaces | ||||||||

| Whatley et al., 2015 [55] | Australia; Participants recruited from the staff, volunteers, participants, and support workers of a local community garden programme based in an inner city area of Melbourne. | Mind Sprout Supported Community Garden (Sprout): a local voluntary sector program offering 3 days per weeks to participants living in the local area who experienced mental ill-health, supported by staff, volunteers (some of whom had past mental health problems), and support workers from the participants’ mental health teams. The intervention comprised gardening activities, a weekly community kitchen, food enterprises, creative projects group, micro-enterprises, a weekly market, and a monthly community market. | The community garden model aimed to help enable occupational participation and social inclusion for people experiencing mental ill-health |

|

| Three inter-related themes:

| It was felt that having responsibility for working on the Sprout market stalls could create anticipatory anxiety for some participants, given the expectation of them running the stall smoothly. However, this seemed to be mitigated through the benefits gained in the social connections forged through the process of running the stall. |

|

| Study (Author & Year) | Country/Setting | Place-Based Intervention (by Category) | Theory of Change/Likely Mechanisms | Sample Size and Characteristics (Total Size, % Female, Mean Age) | Means of Data Collection, Type of Data Collected | Analytic Approach | Key Findings (Effect Sizes, Key Themes, Efforts to Combine Findings from Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis) | Potential Harms Identified | Methodological Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active engagement in local green spaces | |||||||||

| Gerber et al., 2017 [56] | United States; Bhutanese refuges recruited from local community garden and Bhutanese community network | Local community gardening at two local community plots. Authors clarified that these were in an urban area, and that some participants had to use the bus to access the gardens, but all were local to residents. |

|

| Quantitative data: Structured questionnaires to collect cross-sectional data on:

Semi-structured interviews to explore social support issues (such as the nature of social interactions whilst gardening), local acculturation (such as degree of adjustment to life in the US), and perceived advantages and disadvantages of the community garden. Group meetings were held with participants to study findings and explore implications. | Descriptive analysis of quantitative data. Adapted form of thematic analysis of interview transcripts for 8 gardeners and 4 non-gardeners, using the approach of Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR), which involved both deductive and inductive methods to code and interpret data. Focus groups were then used to discuss findings of analyses of the data above to gain feedback on results and consider implications in a culturally salient way. | Quantitative:

| None |

|

| Chiumento et al., 2018 [57] | United Kingdom; Children recruited from 3 schools in the North West of England (two primary schools and one secondary school) | Haven Green Space school garden project, involving monthly sessions over the course of 6 months in which schoolchildren were supported at school by two horticulturists and a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) psychotherapist to work together in designing a green space | Promote positive mental, emotional and physical wellbeing of the children with the “Five Ways to Wellbeing” framework (Connecting with others; Being active; Taking notice of the local environment and of their feelings; learning horticultural skills and how to manage successes and failure; Giving back to the wider community | 36 children (14 females)

| Quantitative data: Collection of pre- and post- intervention scores on the following measures for children

collected over the course of 2 h workshops (pre- and post- intervention) by using the Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment (MWIA) to plot data in a participatory way with children under the following three domains:

| Quantitative analysis: Statistical comparison of scores on pre- and post- intervention measures. Qualitative analysis: thematic analysis of data, with the coding process deductively driven by the MWIA themes. Separate analyses of the quantitative and qualitative data then converged in the discussion to triangulate findings. | Quantitative: -wellbeing scores not found to be statistically significantly different from pre- to post- intervention (although no test statistics were presented to support this statement) Qualitative: Analysis of MWIA plots produced during workshops identified pre- and post-intervention tendencies towards pro-social behaviour (“feeling involved”, “having a valued role”, “sense of belonging” and “social networks and relationships”) and emotional symptoms. The thematic analysis also found that factors relating to mental health and wellbeing were positively impacted, including “emotional wellbeing” and “self-help”. | None |

|

| Category of Study Designs | Methodological Quality Criterion | Levinger et al., 2020 | Wang et al., 2020 | Jalaludin et al., 2012 | Carolan et al., 2011 | Whatley et al., 2015 | Gerber 2017 | Chiumento et al., 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening questions | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Qualitative studies | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Quantitative non-randomized studies | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? | × | √ | √ | N/A | N/A | √ | √ |

| 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | √ | √ | × | N/A | N/A | √ | × | |

| 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? | √ | √ | √ | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | |

| 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | √ | × | √ | N/A | N/A | √ | × | |

| 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | √ | √ | √ | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | |

| Mixed methods studies | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed method design to address the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ |

| 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | |

| 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | |

| 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | √ | |

| 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | √ | × | |

| % of criteria met | 80% | 80% | 80% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 60% |

References

- Perlman, D. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy; John Wiley & Sons Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 36, ISBN 0-471-08028-4. [Google Scholar]

- Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Galvano, D.; Favaro, A.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Noventa, V.; Favaretto, E.; Tudor, F.; Finessi, M.; Shin, J.I.; et al. Factors Associated with Loneliness: An Umbrella Review of Observational Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 271, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HM Government. A Connected Society: A Strategy for Tackling Loneliness–Laying the Foundations for Change; Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS): London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/936725/6.4882_DCMS_Loneliness_Strategy_web_Update_V2.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Park, C.; Majeed, A.; Gill, H.; Tamura, J.; Ho, R.C.; Mansur, R.B.; Nasri, F.; Lee, Y.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Wong, E. The Effect of Loneliness on Distinct Health Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, H.; Evans, J.J.; Nowland, R.; Ferguson, E.; O’Connor, R.C. Loneliness as a Predictor of Suicidal Ideation and Behaviour: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Caballero, F.F.; Martín-María, N.; Cabello, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Miret, M. Association of Loneliness with All-Cause Mortality: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.J.; Cullen, B.; Graham, N.; Lyall, D.M.; Mackay, D.; Okolie, C.; Pearsall, R.; Ward, J.; John, A.; Smith, D.J. Living Alone, Loneliness and Lack of Emotional Support as Predictors of Suicide and Self-Harm: A Nine-Year Follow up of the UK Biobank Cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mann, F.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ma, R.; Johnson, S. Associations between Loneliness and Perceived Social Support and Outcomes of Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barreto, M.; Victor, C.; Hammond, C.; Eccles, A.; Richins, M.T.; Qualter, P. Loneliness around the World: Age, Gender, and Cultural Differences in Loneliness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 169, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Haidt, J.; Blake, A.B.; McAllister, C.; Lemon, H.; Le Roy, A. Worldwide Increases in Adolescent Loneliness. J. Adolesc. 2021, 93, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Cohen, J.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Harrington, H.; Milne, B.J.; Poulton, R. Prior Juvenile Diagnoses in Adults with Mental Disorder: Developmental Follow-Back of a Prospective-Longitudinal Cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninotto, P.; Iob, E.; Demakakos, P.; Steptoe, A. Immediate and Longer-Term Changes in the Mental Health and Well-Being of Older Adults in England during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tilburg, T.G.; Steinmetz, S.; Stolte, E.; van der Roest, H.; de Vries, D.H. Loneliness and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study among Dutch Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e249–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, T.V.; Bu, F.; Dissing, A.S.; Elsenburg, L.K.; Bustamante, J.J.H.; Matta, J.; van Zon, S.K.R.; Brouwer, S.; Bültmann, U.; Fancourt, D.; et al. Loneliness, Worries, Anxiety, and Precautionary Behaviours in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Analysis of 200,000 Western and Northern Europeans. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 2, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrea, R.; Stimson, R.; Western, J. Testing a Moderated Model of Satisfaction with Urban Living Using Data for Brisbane-South East Queensland, Australia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 72, 121–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitley, R.; Prince, M. Fear of Crime, Mobility and Mental Health in Inner-City London, UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezza, M.; Pacilli, M.G. Current Fear of Crime, Sense of Community, and Loneliness in Italian Adolescents: The Role of Autonomous Mobility and Play during Childhood. J. Commun. Psychol. 2007, 35, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Galea, S. Are Neighborhood Characteristics Associated with Depressive Symptoms? A Critical Review. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2008, 62, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.; Knuiman, M. Creating Sense of Community: The Role of Public Space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; MacMillan, T. The Benefits of Gardening for Older Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Act. Adapt. Aging 2013, 37, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.B.; Wrigley, J. Can a Neighbourhood Approach to Loneliness Contribute to People’s Well-Being; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/can-neighbourhood-approach-loneliness-contribute-peoples-well-being (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Tillmann, S.; Tobin, D.; Avison, W.; Gilliland, J. Mental Health Benefits of Interactions with Nature in Children and Teenagers: A Systematic Review. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2018, 72, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.; Odgers, C.L.; Danese, A.; Fisher, H.L.; Newbury, J.B.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Loneliness and Neighborhood Characteristics: A Multi-Informant, Nationally Representative Study of Young Adults. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugel, E.J.; Carpiano, R.M.; Henderson, S.B.; Brauer, M. Exposure to Natural Space, Sense of Community Belonging, and Adverse Mental Health Outcomes across an Urban Region. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malberg Dyg, P.; Christensen, S.; Peterson, C.J. Community Gardens and Wellbeing amongst Vulnerable Populations: A Thematic Review. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ige-Elegbede, J.; Pilkington, P.; Orme, J.; Williams, B.; Prestwood, E.; Black, D.; Carmichael, L. Designing Healthier Neighbourhoods: A Systematic Review of the Impact of the Neighbourhood Design on Health and Wellbeing. Cities Health 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C.R.; Pikhartova, J. Lonely Places or Lonely People? Investigating the Relationship between Loneliness and Place of Residence. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, E.; Motoc, I.; Noordzij, J.M.; Beenackers, M.A.; Wissa, R.; Sarr, A.; Gurer, A.; Fabre, G.; Ruiz, M.; Doiron, D. Social and Physical Neighbourhood Characteristics and Loneliness among Older Adults: Results from the MINDMAP Project. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2021, 75, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, A.; Tarkhanyan, L.; Vaughan, L. Estimating Pedestrian Demand for Active Transport Evaluation and Planning. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boniface, S.; Scantlebury, R.; Watkins, S.J.; Mindell, J.S. Health Implications of Transport: Evidence of Effects of Transport on Social Interactions. J. Transp. Health 2015, 2, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.Y.; Sarkar, C.; Kumari, S.; Ni, M.Y.; Gallacher, J.; Webster, C. Calculating a National Anomie Density Ratio: Measuring the Patterns of Loneliness and Social Isolation across the UK’s Residential Density Gradient Using Results from the UK Biobank Study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 215, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, J.; Goodfellow, C.; Hardoon, D.; Inchley, J.; Leyland, A.; Qualter, P.; Simpson, S.A.; Long, E. Loneliness in Young People: A Multilevel Exploration of Social Ecological Influences and Geographic Variation. J. Public Health 2021, fdab402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONS Mapping Loneliness during the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/mappinglonelinessduringthecoronaviruspandemic/2021-04-07 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Krabbendam, L.; van Vugt, M.; Conus, P.; Söderström, O.; Empson, L.A.; van Os, J.; Fett, A.-K.J. Understanding Urbanicity: How Interdisciplinary Methods Help to Unravel the Effects of the City on Mental Health. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, M.J.; Pirani, M.; Booth, E.R.; Shen, C.; Milligan, B.; Jones, K.E.; Toledano, M.B. Benefit of Woodland and Other Natural Environments for Adolescents’ Cognition and Mental Health. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrie, M.P.; Shortt, N.K.; Mitchell, R.J.; Taylor, A.M.; Redmond, P.; Thompson, C.W.; Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J.; Pearce, J.R. Green Space and Cognitive Ageing: A Retrospective Life Course Analysis in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 196, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherrie, M.P.; Shortt, N.K.; Ward Thompson, C.; Deary, I.J.; Pearce, J.R. Association between the Activity Space Exposure to Parks in Childhood and Adolescence and Cognitive Aging in Later Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pearce, J.; Cherrie, M.; Shortt, N.; Deary, I.; Ward Thompson, C. Life Course of Place: A Longitudinal Study of Mental Health and Place. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2018, 43, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergefurt, L.; Kemperman, A.; van den Berg, P.; Borgers, A.; van der Waerden, P.; Oosterhuis, G.; Hommel, M. Loneliness and Life Satisfaction Explained by Public-Space Use and Mobility Patterns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackman, T.; Harvey, J.; Lawrence, M.; Simon, A. Neighbourhood Renewal and Health: Evidence from a Local Case Study. Health Place 2001, 7, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ONS Loneliness. What Characteristics and Circumstances Are Associated with Feeling Lonely? 2018. Available online: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/lonely-society (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Griffin, J. The Lonely Society? Mental Health Foundation: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, C.M.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Reduce Loneliness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. Off. J. Soc. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Inc 2011, 15, 219–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osborn, T.; Weatherburn, P.; French, R.S. Interventions to Address Loneliness and Social Isolation in Young People: A Systematic Review of the Evidence on Acceptability and Effectiveness. J. Adolesc. 2021, 93, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J.; Harris, C.; Eadson, W.; Gore, T. Space to Thrive: A Rapid Evidence Review of the Benefits of Parks and Green Spaces for People and Communities. 2019. Available online: https://www.shu.ac.uk/centre-regional-economic-social-research/publications/space-to-thrive-a-rapid-evidence-review-of-the-benefits-of-parks-and-green-spaces-for-people (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Moore, T.H.M.; Kesten, J.M.; López-López, J.A.; Ijaz, S.; McAleenan, A.; Richards, A.; Gray, S.; Savović, J.; Audrey, S. The Effects of Changes to the Built Environment on the Mental Health and Well-Being of Adults: Systematic Review. Health Place 2018, 53, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Mooney, S.J.; Muennig, P.; DiMaggio, C. Cause and Context: Place-Based Approaches to Investigate How Environments Affect Mental Health. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Giacco, D.; Forsyth, R.; Nebo, C.; Mann, F.; Johnson, S. Social Isolation in Mental Health: A Conceptual and Methodological Review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pace, R.; Pluye, P.; Bartlett, G.; Macaulay, A.C.; Salsberg, J.; Jagosh, J.; Seller, R. Testing the Reliability and Efficiency of the Pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinger, P.; Panisset, M.; Dunn, J.; Haines, T.; Dow, B.; Batchelor, F.; Biddle, S.; Duque, G.; Hill, K.D. Exercise InterveNtion Outdoor ProJect in the COmmunitY for Older People—Results from the ENJOY Seniors Exercise Park Project Translation Research in the Community. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalaludin, B.; Maxwell, M.; Saddik, B.; Lobb, E.; Byun, R.; Gutierrez, R.; Paszek, J. A Pre-and-Post Study of an Urban Renewal Program in a Socially Disadvantaged Neighbourhood in Sydney, Australia. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carolan, M.; Onaga, E.; Pernice-Duca, F.; Jimenez, T. A Place to Be: The Role of Clubhouses in Facilitating Social Support. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2011, 35, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatley, E.; Fortune, T.; Williams, A.E. Enabling Occupational Participation and Social Inclusion for People Recovering from Mental Ill-Health through Community Gardening. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2015, 62, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.M.; Callahan, J.L.; Moyer, D.N.; Connally, M.L.; Holtz, P.M.; Janis, B.M. Nepali Bhutanese Refugees Reap Support Through Community Gardening. Int. Perspect. Psychol. 2017, 6, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumento, A.; Mukherjee, I.; Chandna, J.; Dutton, C.; Rahman, A.; Bristow, K. A Haven of Green Space: Learning from a Pilot Pre-Post Evaluation of a School-Based Social and Therapeutic Horticulture Intervention with Children. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, C.; Yeh, C.H. Community Canteen Services for the Rural Elderly: Determining Impacts on General Mental Health, Nutritional Status, Satisfaction with Life, and Social Capital. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hemming, K.; Taljaard, M.; Forbes, A. Analysis of Cluster Randomised Stepped Wedge Trials with Repeated Cross-Sectional Samples. Trials 2017, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E. Framework for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions: Gap Analysis, Workshop and Consultation-Informed Update. Health Technol. Assess. 2021, 25, 1–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birckmayer, J.D.; Weiss, C.H. Theory-Based Evaluation in Practice: What Do We Learn? Eval. Rev. 2000, 24, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, M.J.; Breuer, E.; Lee, L.; Asher, L.; Chowdhary, N.; Lund, C.; Patel, V. Theory of Change: A Theory-Driven Approach to Enhance the Medical Research Council’s Framework for Complex Interventions. Trials 2014, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortegon-Sanchez, A.; McEachan, R.R.; Albert, A.; Cartwright, C.; Christie, N.; Dhanani, A.; Islam, S.; Ucci, M.; Vaughan, L. Measuring the Built Environment in Studies of Child Health—A Meta-Narrative Review of Associations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 10741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macintyre, S.; Ellaway, A.; Cummins, S. Place Effects on Health: How Can We Conceptualise, Operationalise and Measure Them? Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, C.; Foden, M.; Grimsley, M.; Lawless, P.; Wilson, I. Four Years of Change? Understanding the Experiences of the 2002–2006 New Deal for Communities Panel: Evidence from the New Deal for Communities Programme Main Report; Department for Communities and Local Government; HMSO: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 1-4098-1478-5. Available online: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/29253/1/Four%20years%20of%20change%20main%20report.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- HM Government National Planning Policy Framework. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government; HMSO: London, UK, 2012. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1005759/NPPF_July_2021.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Loneliness. A Connected Recovery; Red Cross: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.redcross.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/action-on-loneliness/all-party-parliamentary-group-on-loneliness-inquiry/a-connected-recovery (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- HM Government. Tackling Loneliness Evidence Review; Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), HMSO: London, UK, 2022.

- Zimmerman, F.J. Population Health Science: Fulfilling the Mission of Public Health. Milbank Q. 2021, 99, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, F.; Wang, J.; Pearce, E.; Ma, R.; Schlief, M.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Johnson, S. Loneliness and the Onset of New Mental Health Problems in the General Population: A Systematic Review. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, L.; Hobbs, M.; Wiki, J.; Kingham, S.; Campbell, M. The Good, the Bad, and the Environment: Developing an Area-Based Measure of Access to Health-Promoting and Health-Constraining Environments in New Zealand. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2021, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Badland, H.; Kvalsvig, A.; O’Connor, M.; Christian, H.; Woolcock, G.; Giles-Corti, B.; Goldfeld, S. Can the Neighborhood Built Environment Make a Difference in Children’s Development? Building the Research Agenda to Create Evidence for Place-Based Children’s Policy. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pescheny, J.V.; Randhawa, G.; Pappas, Y. The Impact of Social Prescribing Services on Service Users: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsueh, Y.-C.; Batchelor, R.; Liebmann, M.; Dhanani, A.; Vaughan, L.; Fett, A.-K.; Mann, F.; Pitman, A. A Systematic Review of Studies Describing the Effectiveness, Acceptability, and Potential Harms of Place-Based Interventions to Address Loneliness and Mental Health Problems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084766

Hsueh Y-C, Batchelor R, Liebmann M, Dhanani A, Vaughan L, Fett A-K, Mann F, Pitman A. A Systematic Review of Studies Describing the Effectiveness, Acceptability, and Potential Harms of Place-Based Interventions to Address Loneliness and Mental Health Problems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084766

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsueh, Yung-Chia, Rachel Batchelor, Margaux Liebmann, Ashley Dhanani, Laura Vaughan, Anne-Kathrin Fett, Farhana Mann, and Alexandra Pitman. 2022. "A Systematic Review of Studies Describing the Effectiveness, Acceptability, and Potential Harms of Place-Based Interventions to Address Loneliness and Mental Health Problems" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084766

APA StyleHsueh, Y.-C., Batchelor, R., Liebmann, M., Dhanani, A., Vaughan, L., Fett, A.-K., Mann, F., & Pitman, A. (2022). A Systematic Review of Studies Describing the Effectiveness, Acceptability, and Potential Harms of Place-Based Interventions to Address Loneliness and Mental Health Problems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084766