A Special Class of Experience: Positive Affect Evoked by Music and the Arts

Abstract

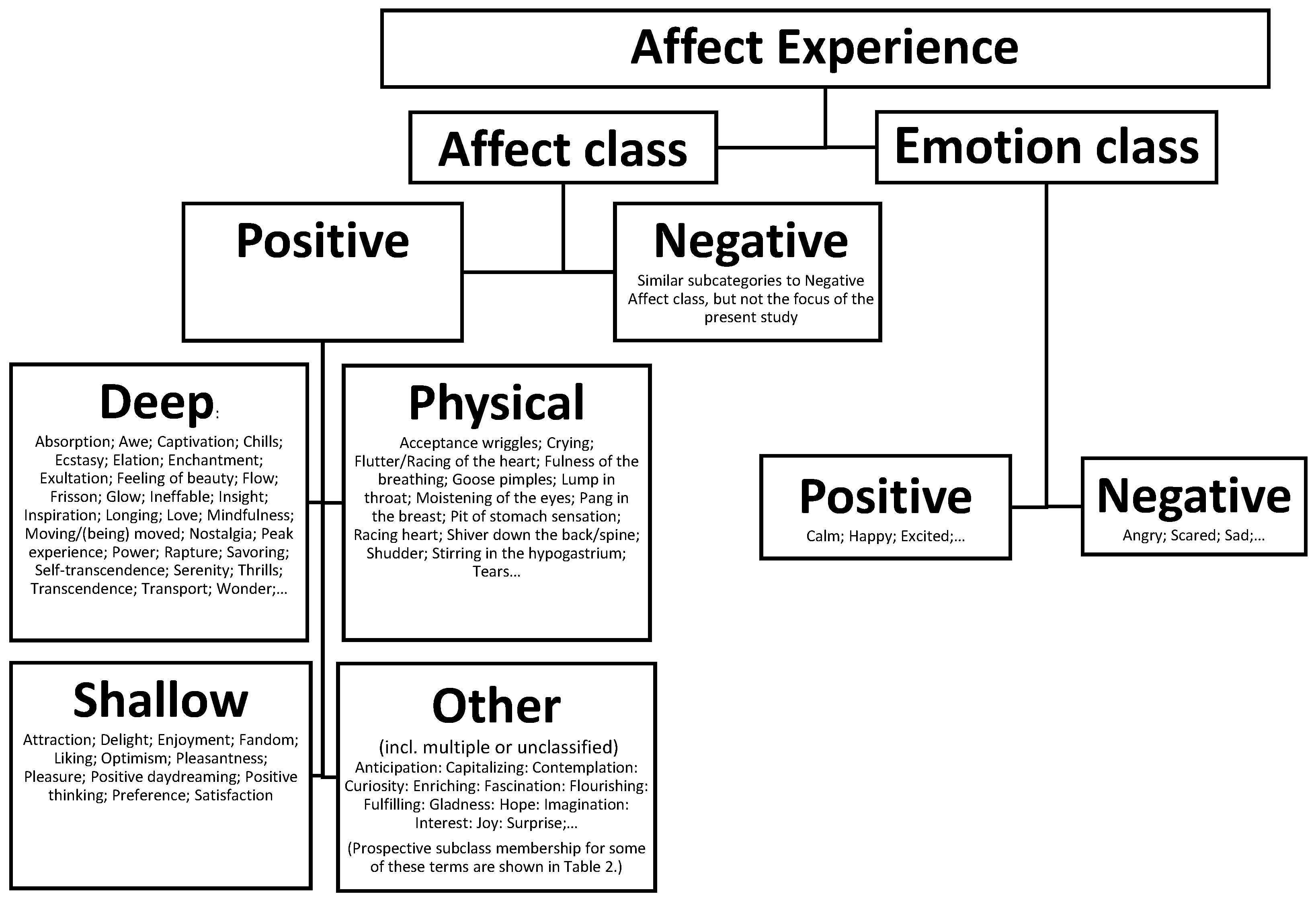

1. Introduction

the most elementary consciously accessible affective feelings (and their neurophysiological counterparts) that need not be directed at anything. Examples include a sense of pleasure or displeasure, tension or relaxation, and depression or elation. Core affect ebbs and flows over the course of time. Although core affect is not necessarily consciously directed at anything—it can be free-floating (p. 806).

2. Aesthetic Emotion Words

3. Subtle, Coarse, Pseudo, and Real

These secondary emotions themselves are assuredly for the most part constituted of other incoming sensations aroused by the diffusive wave of reflex effects which the beautiful object sets up. A glow, a pang in the breast, a shudder, a fulness of the breathing, a flutter of the heart, a shiver down the back, a moistening of the eyes, a stirring in the hypogastrium, and a thousand unnamable symptoms besides, may be felt the moment the beauty excites us. ([40] (p. 470), italics as in the source)

How far can unpleasantness go before it is incompatible with aesthetic enjoyment? Can a person enjoy music and have an unpleasant emotion at the same time? Are there mixed feelings? Such troublesome questions as these must be answered if it is assumed that a person’s pleasure in a work of art can be accompanied by displeasure, but they need never be raised if it is discovered that the so-called emotions are really not emotions at all, but are characters of the music which bear a striking formal resemblance to emotion [44] (pp. 199–200).

4. Refined Emotions

[R]efinement represents a mode of perhaps all emotions that language or emotion taxonomy could distinguish. There exist refined anger, love, and sexual ecstasy, as well as coarse, straightforward anger, love, and sexual ecstasy. (p. 227)

5. Flow, Absorption, and Concepts in Positive Psychology

(a) elation, gladness, and joy …; (b) awe …, wonder …, inspiration …; (c) mindfulness …, insight …, and self-transcendence …; (d) hope …, optimism …, and positive thinking …; (e) imagination …, anticipation …, and positive daydreaming …; (f) absorption …, flow …, and peak experience …; and (g) flourishing …, capitalizing …, and savoring …. (pp. 61–62)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

experiences in which the individual transcends ordinary reality and perceives Being or ultimate reality. Peak experiences are typically of short duration and accompanied by positive affect. Peak experiences teach the individual that the universe is ultimately good or neutral, not evil; that the ultimate good is composed of Being-values such as truth, goodness, wholeness, beauty, dichotomy-transcendence, aliveness, uniqueness, perfection, necessity, completion, justice, order, simplicity, richness, effortlessness, playfulness, and self-sufficiency; and that opposites really do not exist. As a result of having had a peak experience the individual is usually changed so that he or she is more psychologically healthy. (p. 93)

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berridge, K.C.; Kringelbach, M.L. Building a neuroscience of pleasure and well-being. Psychol. Well-Being Theory Res. Pract. 2011, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review; Health Evidence Network (HEN) Synthesis Report 67; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, F.A.; Baylis, N.; Keverne, B. Int-roduction: Why do we need a science of well–being? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004, 359, 1331–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mastandrea, S.; Fagioli, S.; Biasi, V. Art and Psychological Well-Being: Linking the Brain to the Aesthetic Emotion. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielsson, A. Strong Experiences with Music: Music Is Much More than Just Music; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, E. Loved music can make a listener feel negative emotions. Musicae Sci. 2013, 17, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. Glad to be sad, and other examples of benign masochism. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2013, 8, 439–447. [Google Scholar]

- Huron, D. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Huron, D. Aesthetics. In The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology; Hallam, S., Cross, I., Thaut, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Juslin, P.N. Musical Emotions Explained: Unlocking the Secrets of Musical Affect; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Deeper than Reason: Emotion and Its Role in Literature, Music, and Art; Clarendon: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kivy, P. Sound Sentiment: An Essay on the Musical Emotions, Including the Complete Text of the Corded Shell; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hanich, J.; Wagner, V.; Shah, M.; Jacobsen, T.; Menninghaus, W. Why we like to watch sad films. The pleasure of being moved in aesthetic experiences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuoskoski, J.K.; Eerola, T. The pleasure evoked by sad music is mediated by feelings of being moved. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.B. Emotion and Meaning in Music; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, J. Music and negative emotions. In Music, Art and Metaphysics: Essays in Philosophical Aesthetics; Levinson, J., Ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 306–335. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, T.; Roy, A.R.K.; Welker, K.M. Music as an emotion regulation strategy: An examination of genres of music and their roles in emotion regulation. Psychol. Music 2019, 47, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, H.; Oepen, R. Emotion regulation strategies and effects in art-making: A narrative synthesis. Arts Psychother. 2018, 59, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingle, G.A.; Williams, E.; Jetten, J.; Welch, J. Choir singing and creative writing enhance emotion regulation in adults with chronic mental health conditions. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. Poetics. In Aristotle’s Theory of Poetry and Fine Art; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz, G.; Ott, U.; Teichmann, D.; Osawa, P.; Vaitl, D. Using music to induce emotions: Influences of musical preference and absorption. Psychol. Music 2007, 36, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E. Enjoyment of negative emotions in music: An associative network explanation. Psychol. Music 1996, 24, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E. Enjoying sad music: Paradox or parallel processes? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charland, L. The heat of emotion: Valence and the demarcation problem. J. Conscious. Stud. 2005, 8, 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Barrett, L.F. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called Emotion: Dissecting the elephant. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A.R. Descartes Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain; G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, E.; North, A.C.; Hargreaves, D.J. Aesthetic Experience explained by the Affect-space framework. Empir. Musicol. Rev. 2016, 11, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, T. What is it like to be a bat? Philos. Rev. 1974, 83, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, D.C. Quining qualia. In Consciousness in Modern Science; Marcel, A.J., Bisiach, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 42–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chumley, L.H.; Harkness, N. Introduction: QUALIA. Anthropol. Theory 2013, 13, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyer, P. History of Modern Aesthetics. In The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics; Levinson, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, D. From Shaftesbury to Kant: The development of the concept of aesthetic experience. J. Hist. Ideas 1987, 48, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslin, P.N. From everyday emotions to aesthetic emotions: Towards a unified theory of musical emotions. Phys. Life Rev. 2013, 10, 235–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konečni, V.J. The aesthetic trinity: Awe, being moved, thrills. Bull. Psychol. Arts 2005, 5, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, I.; Hosoya, G.; Menninghaus, W.; Beermann, U.; Wagner, V.; Eid, M.; Scherer, K.R. Measuring aesthetic emotions: A review of the literature and a new assessment tool. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariff, A.F.; Tracy, J.L. What Are Emotion Expressions For? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.N. Familiarity and no Pleasure. The Uncanny as an Aesthetic Emotion. Image Narrat. 2010, 11, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, P.J. Looking past pleasure: Anger, confusion, disgust, pride, surprise, and other unusual aesthetic emotions. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2009, 3, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J.; Brown, E.M. Anger, disgust, and the negative aesthetic emotions: Expanding an appraisal model of aesthetic experience. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2007, 1, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W. The Principles of Psychology in Two Volumes; Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1890; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda, J.A. Music structure and emotional response: Some empirical findings. Psychol. Music 1991, 19, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, J.A. Empirical studies of emotional response to music. In Cognitive Bases of Musical Communication; Jones, M.R., Holleran, S., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike, E.L. The Principles of Teaching Based on Psychology; A. G. Seiler: New York, NY, USA, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, C.C. The Meaning of Music; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Kivy, P. Music Alone: Philosophical Reflections on the Purely Musical Experience; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kivy, P. Feeling the musical emotions (A philosophical approach). Br. J. Aesthet. 1999, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. The Cognition-Emotion Debate: A Bit of History. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion; Dalgleish, T., Power, M.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1999; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N.H.; Sundararajan, L. Emotion refinement: A theory inspired by Chinese poetics. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninghaus, W.; Wagner, V.; Hanich, J.; Wassiliwizky, E.; Jacobsen, T.; Koelsch, S. The distancing-embracing model of the enjoyment of negative emotions in art reception. Behav. Brain Sci. 2017, 40, e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, E. Psychical distance as a factor in art and an aesthetic principle. Br. J. Psychol. 1912, 5, 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology: The Collected Works of Mihaly; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, A. Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the experience of flow. Conscious. Cogn. 2004, 13, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.A.; Thomas, P.R.; Marsh, H.W.; Smethurst, C.J. Relationships between flow, self-concept, psychological skills, and performance. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2001, 13, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Jackson, S.A. Brief approaches to assessing task absorption and enhanced subjective experience: Examining ‘short’ and ‘core’ flow in diverse performance domains. Motiv. Emot. 2008, 32, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Classic Work on How to Achieve Happiness; Rev, Ed.; Rider: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen, A.; Atkinson, G. Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1974, 83, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellegen, A. Practicing the two disciplines for relaxation and enlightenment: Comment on “Role of the feedback signal in electromyograph biofeedback: The relevance of attention” by Qualls and Sheehan. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1981, 110, 217–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, G.M.; Russo, F.A. Absorption in music: Development of a scale to identify individuals with strong emotional responses to music. Psychol. Music 2013, 41, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkins, S.S. Affect as amplification: Some modifications in theory. In Theories of Emotion; Plutchik, R., Keilerman, H., Eds.; Emotion: Theory, Research, and Experience; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, S.S. Affect, Imagery, Consciousness; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, F.B.; King, S.P.; Smart, C.M. Multivariate statistical strategies for construct validation in positive psychology. In Oxford Handbook of Methods in Positive Psychology; Ong, A.D., Van Dulmen, M.H.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zickfeld, J.H.; Schubert, T.W.; Seibt, B.; Blomster, J.K.; Arriaga, P.; Basabe, N.; Blaut, A.; Caballero, A.; Carrera, P.; Dalgar, I.; et al. Kama muta: Conceptualizing and measuring the experience often labelled being moved across 19 nations and 15 languages. Emotion 2019, 19, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.P.; Schubert, T.W.; Seibt, B. “Kama muta” or “being moved by love”: A bootstrapping approach to the ontology and epistemology of an emotion. In Universalism without Uniformity: Explorations in Mind and Culture; Cassaniti, J., Menon, U., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Steinnes, K.K.; Blomster, J.K.; Seibt, B.; Zickfeld, J.H.; Fiske, A.P. Too Cute for Words: Cuteness Evokes the Heartwarming Emotion of Kama Muta. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.P.; Seibt, B.; Schubert, T. The Sudden Devotion Emotion: Kama Muta and the Cultural Practices Whose Function Is to Evoke It. Emot. Rev. 2019, 11, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E.; Hargreaves, D.J.; North, A.C. Empirical test of aesthetic experience using the affect-space framework. Psychomusicol. Music. Mind Brain 2019, 30, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Brandenstein, C.G. Portuguese Loan-words in Aboriginal Languages of North-western Australia (a problem of Indo-European and Finno-Ugrian comparative linguistics). In Pacific Linguistic Studies in Honour of Arthur Capell; Wurm, S.A., Laycock, D.C., Eds.; Pacific Linguistics: Canberra, Australia, 1970; pp. 617–650. [Google Scholar]

- Mischler, J.J., III. Metaphor across Time and Conceptual Space: The Interplay of Embodiment and Cultural Models; John Benjamins Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Leskovec, J.; Jurafsky, D. Diachronic word embeddings reveal statistical laws of semantic change. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; pp. 1489–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, R.X.; Franke, M.; Smith, K.; Goodman, N.D. Emerging abstractions: Lexical conventions are shaped by communicative context. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (CogSci 2018), Madison, WI, USA, 25–28 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, B.; Perlman, M.; Majid, A. Vision dominates in perceptual language: English sensory vocabulary is optimized for usage. Cognition 2018, 179, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diller, H.-J. Contempt: The main growth area in the Elizabethan emotion lexicon. In Words in Dictionaries and History; Timofeeva, O., Säily, T., McConchie, R.W., Eds.; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Colver, M.C.; El-Alayli, A. Getting aesthetic chills from music: The connection between openness to experience and frisson. Psychol. Music 2016, 44, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewe, O.; Katzur, B.; Kopiez, R.; Altenmüller, E. Chills in different sensory domains: Frisson elicited by acoustical, visual, tactile and gustatory stimuli. Psychol. Music 2011, 39, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S.; Jäncke, L. Music and the heart. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3043–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, K. On the nature and function of emotion: A component process approach. Approaches Emot. 1984, 2293, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E. The fundamental function of music. Musicae Sci. 2009, 13, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanselow, M.S. Emotion, motivation and function. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2018, 19, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.L. Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, A. Music and Flourishing. In The Oxford Handbook of the Positive Humanities; Tay, L., Pawelski, J.O., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Croom, A. Music, Neuroscience, and the Psychology of Well-Being: A Précis. Front. Psychol. 2012, 2, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Särkämö, T.; Tervaniemi, M.; Huotilainen, M. Music perception and cognition: Development, neural basis, and rehabilitative use of music. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 2013, 4, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathes, E.W. Peak Experience Tendencies: Scale Development and Theory Testing. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1982, 22, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.; Kern, M.L. The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Grouping | Explanation of Grouping | Subscale Labels 1 | Role in Present Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prototypical aesthetic emotions | “capture aesthetic appreciation irrespective of the pleasingness” | (1) feeling of beauty/liking, (2) fascination, (3) being moved, (4) awe (and, more weakly, (5) enchantment/wonder and (6) nostalgia/longing). | This links well to the proposed conceptualization of positive affect class. |

| Pleasing emotions † | “all emotions with positive affective valence” | (7) joy, (8) humour, (9) vitality, (10) energy, and (11) relaxation | This links fairly well to the proposed conceptualization of positive affect class, but may also be well suited to the emotion class (e.g., relaxation). |

| Epistemic emotions * | “the search for and finding of meaning during aesthetic experiences” | (12) surprise, (13) interest, (14) intellectual challenge, and (15) insight | These subscales can be characterised as a positive affect class or as a separate experiential class. |

| Negative emotions | “emotions often are felt during aesthetic experiences that not only are unpleasant but also contribute to a negative evaluation regarding aesthetic merit” | (16) feeling of ugliness, (17) boredom, (18) confusion, (19) anger, (20) uneasiness, and (21) sadness. | Omitted because it could include an other-than-positive experience. |

- 1 Subscale labels and explanations are taken from [35].

- * Adopted as part of the affect class experience in the present paper;

- † adopted as part of the emotion class of experience as part of the present paper; other groupings not adopted.

| Affect Term 1 | Subclass 2 | Source 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Deep | f |

| Acceptance wriggles | Physical | [48] |

| Anticipation | Shallow | e |

| Attraction PAE | Shallow | [35] |

| Awe PAE | Deep | b, [27,35] |

| Capitalizing | g | |

| Captivation PAE | Deep | [35] |

| Chills | Physical | [27] |

| Contemplation | Deep | [48] |

| Crying − | Physical | [41] |

| Curiosity | z | |

| Delight | Shallow | [44] |

| Ecstasy | Deep | [44] |

| Elation | Deep | a, [44] |

| Enchantment PAE | Deep | [35] |

| Enjoyment | Shallow | [27,44] |

| Enriching | Deep | z |

| Exhilaration | Deep | [63] |

| Exultation | Deep | [44] |

| Fascination | Deep | z |

| Fandom | Shallow | z |

| Feeling of beauty PAE | Deep | [35] |

| Flourishing | Deep | g |

| Flow | Deep | f |

| Flutter/Racing of the heart | Physical | [40,41] |

| Frisson | Physical | [27] |

| Fulfilling | Deep | z |

| Fulness of the breathing | Physical | [40] |

| Gladness * | Shallow | a |

| Glow | Deep | [40,48] |

| Goose pimples | Physical | [41] |

| Hope | Deep | d |

| Imagination | Shallow | e |

| Ineffable | Deep | z |

| Insight | Deep | c, [35] |

| Inspiration | Deep | b |

| Interest | Shallow | [35] |

| Joy * | Deep | a |

| Kama muta ** | Deep | [63,64,65,66] |

| Liking PAE | Shallow | [27,35] |

| Longing −,PAE | Deep | [35] |

| Love * | Deep | [6] |

| Lump in throat − | Physical | [41] |

| Mindfulness | Deep | c |

| Moistening of the eyes − | Physical | [40] |

| Moving/(being) moved −,PAE,** | Deep | [27,35] |

| Nostalgia PAE | Deep | [35,67] |

| Optimism * | Shallow | d |

| Pang in the breast − | Physical | [40] |

| Peak experience | Deep | f |

| Pit of stomach sensation | Physical | [41] |

| Pleasantness | Shallow | [27,44] |

| Pleasure | Shallow | [44] |

| Positive daydreaming | Shallow | e |

| Positive thinking | Shallow | d |

| Power | Deep | [67] |

| Preference | Shallow | z |

| Racing heart | Physical | [41] |

| Rapture | Deep | [44] |

| Satisfaction | Shallow | z |

| Savoring | Deep | g, [48] |

| Self-transcendence | Deep | c |

| Serenity * | Deep | z |

| Shiver down the back/spine | Physical | [40,41] |

| Shudder − | Physical | [40] |

| Stirring in the hypogastrium † | Physical | [40] |

| Surprise | Shallow | [35] |

| Tears − | Physical | [41] |

| Thrills | Deep | [27] |

| Transcendence | Deep | [27] |

| Transport | Deep | [44] |

| Wonder PAE | Deep | b, [35] |

- 1 Some proposed affect class experience terms are accompanied by notes:

- † Hypogastrium (in the ‘Stirring in the hypogastrium’ entry) is the anatomical structure that best fits the ordinary language description ‘Pit of the stomach’ (see that entry).

- * Examples of terms that may be more commonly used to describe both emotion class and affect class experience.

- − despite being positive affect terms, these marked items have at least some potential negative connotations. It is the context (of contemplating or engaging with music/art) that enables these affects to be experienced as strongly positive.

- ** ‘Kama muta’ is an affect class related to being moved (by love) (see entry ‘Moving…’). It has also been linked to the physical experience subclass because the experience can include ‘tears, chills, warmth in the chest, feeling choked up’ (the latter represented by ’Lump in the throat’ in the table) [63]. Because the term is borrowed from the ancient Sanskrit language [68] and has been relatively recently proposed for adoption into English, it is currently not in common usage.

- PAE Classified as a ‘prototypical aesthetic emotion’ by [25].

- 2 Proposed subclasses of affect class experience: hedonic tone (deep or shallow), and whether experience is described directly in terms of a physical correlate (physical).

- 3 ‘Source’ lists sample sources in which the term was located as an amendable member of the positive affect class of experience. A single letter denotation from a to g indicates one of the seven triads of the 21 positive psychology terms taken from Bryant, King, and Smart [62]. The single letter z is a term proposed in the present paper. Other sources cited in the table are (for more details, see References):

- [6]—Schubert (2013);

- [27]—Schubert, North, and Hargreaves (2016);

- [35]—Schindler et al. (2017);

- [44]—Pratt (1931);

- [48]—Frijda and Sundararajan (2007);

- [63]—Zickfeld et al. (2019);

- [64]—Fiske, Schubert, and Seibt (2017);

- [65]—Steinnes et al. (2019);

- [66]—Fiske, Seibt, and Schubert T. (2019);

- [67]—Schubert, Hargreaves, and North (2019).

| C | (Positive) Affect Class | Emotion Class | S |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Refined, subtle emotions (James) OR a wide range of emotions can be both coarse and refined (Frijda and Sundararajan [48]). Different terms may have considerable overlap in meaning with other affect experiences and may be difficult to clearly distinguish from one another. | Coarse emotions. Generally easy to distinguish from one another. | [40] OR [48] |

| Sample 1 | Awe, moved, wonder, thrills, absorbed, and energised. | Sad, angry, scared, calm, happy, and excited. | [25] |

| Feels like | Savouring of, and yet detachment from, the coarse emotion. | The coarse emotion itself, e.g., feeling sad or feeling happy. | [48] |

| Directedness | Diffuse; difficult to poinpoint the sensation to a particular, unique type, or to a particular object/event, apart from the object/event being engaged with (e.g., frisson, thrills, and chills are overlapping concepts and subtley distinguishable from one another [74,75,76]). The experience may be undescribable in words (ineffable). | Specific, identifiable, self-contained experience (e.g., I feel happy, I feel sad, etc.); focussed on the self or the object causing the emotion (i.e., not as diffuse). | [6,24,25,26] |

| Lexicon | The terminology is poorly established and needs to consider the ineffable. With the possible exception of some ‘aesthetic emotions’ (awe, being moved, wonder, and thrills), there is no prototypical terminology; core affect. | Terminology well established. Prototypical: discrete, definable. | [25] |

| Structure: | An intensity or strength of feeling eminating (usually) from the emotion. Metaphors with temperature (heat), charge, or force/energy of the coarse emotion; embellishment of simultaneous emotion class experience; wholly or in part positive. | Consists of physiological, signalling, feelingful, and motivational components; valence, arousal; can be positive or negative. | [6,21,22,24,48,77,78,79] |

| Function | Powerful, motivating force, without necessarily knowing why (apart from the act of engagement with the object/event); arises through pure contemplation/engagement with a thought, object, or event and is in and of itself a positive; supports exploration of emotions in a safe environment and possibly generates wellbeing. | Various: attraction, neutral, repulsion (including withdrawal, attack); knowing why (e.g., the cause/trigger of the feeling); adapting to the environment; moral, self-reflective, or social change/improvement. | [16,25,36,52,61,80,81,82,83,84] |

- C = conceptual aspect.

- S = sources upon which interpretations of the conceptualization are based.

- 1 See Table 2 for the more extensive, proposed list of affect terms.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schubert, E. A Special Class of Experience: Positive Affect Evoked by Music and the Arts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084735

Schubert E. A Special Class of Experience: Positive Affect Evoked by Music and the Arts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084735

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchubert, Emery. 2022. "A Special Class of Experience: Positive Affect Evoked by Music and the Arts" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084735

APA StyleSchubert, E. (2022). A Special Class of Experience: Positive Affect Evoked by Music and the Arts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084735