Predictors of Sexual Function and Performance in Young- and Middle-Old Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

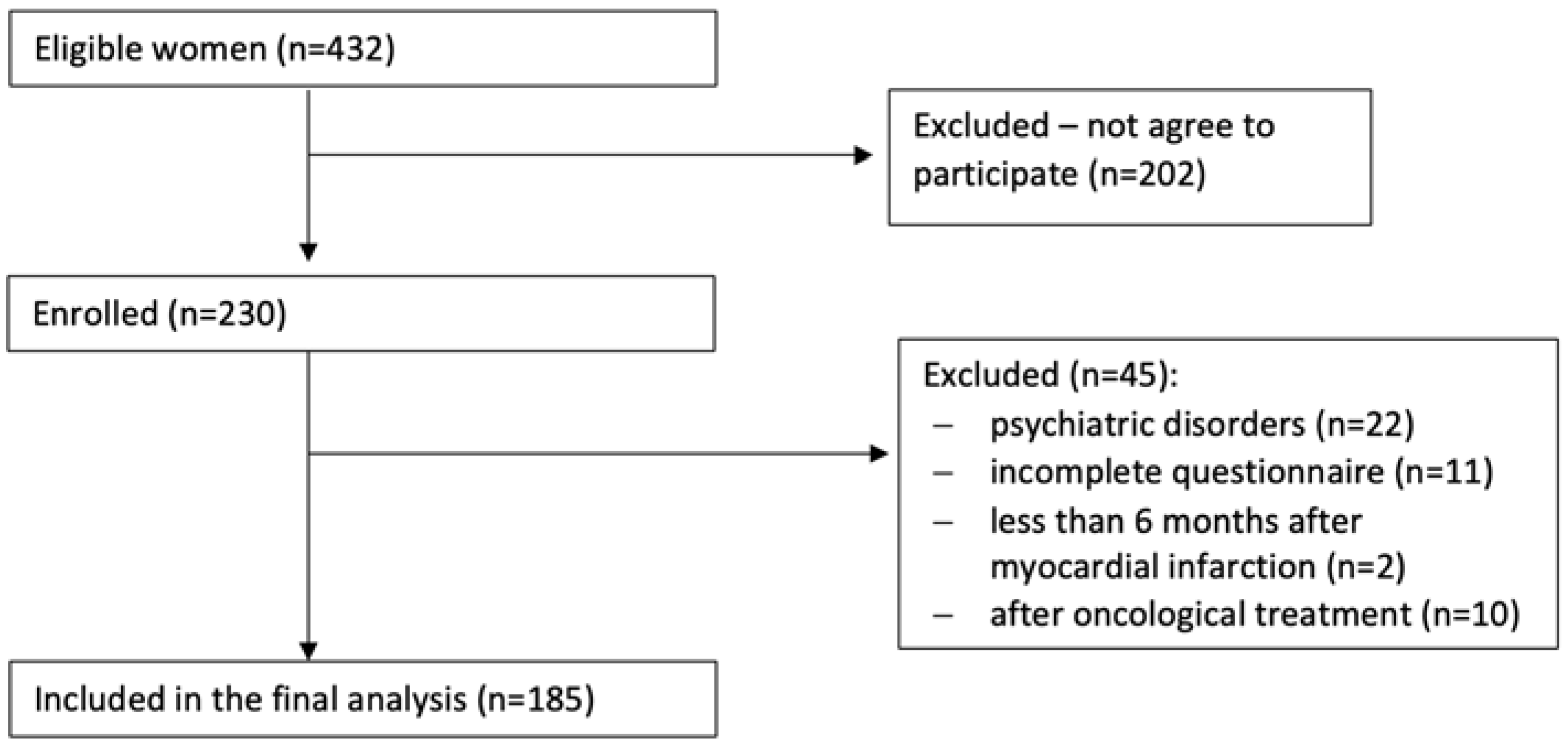

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Study Sample Calculation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

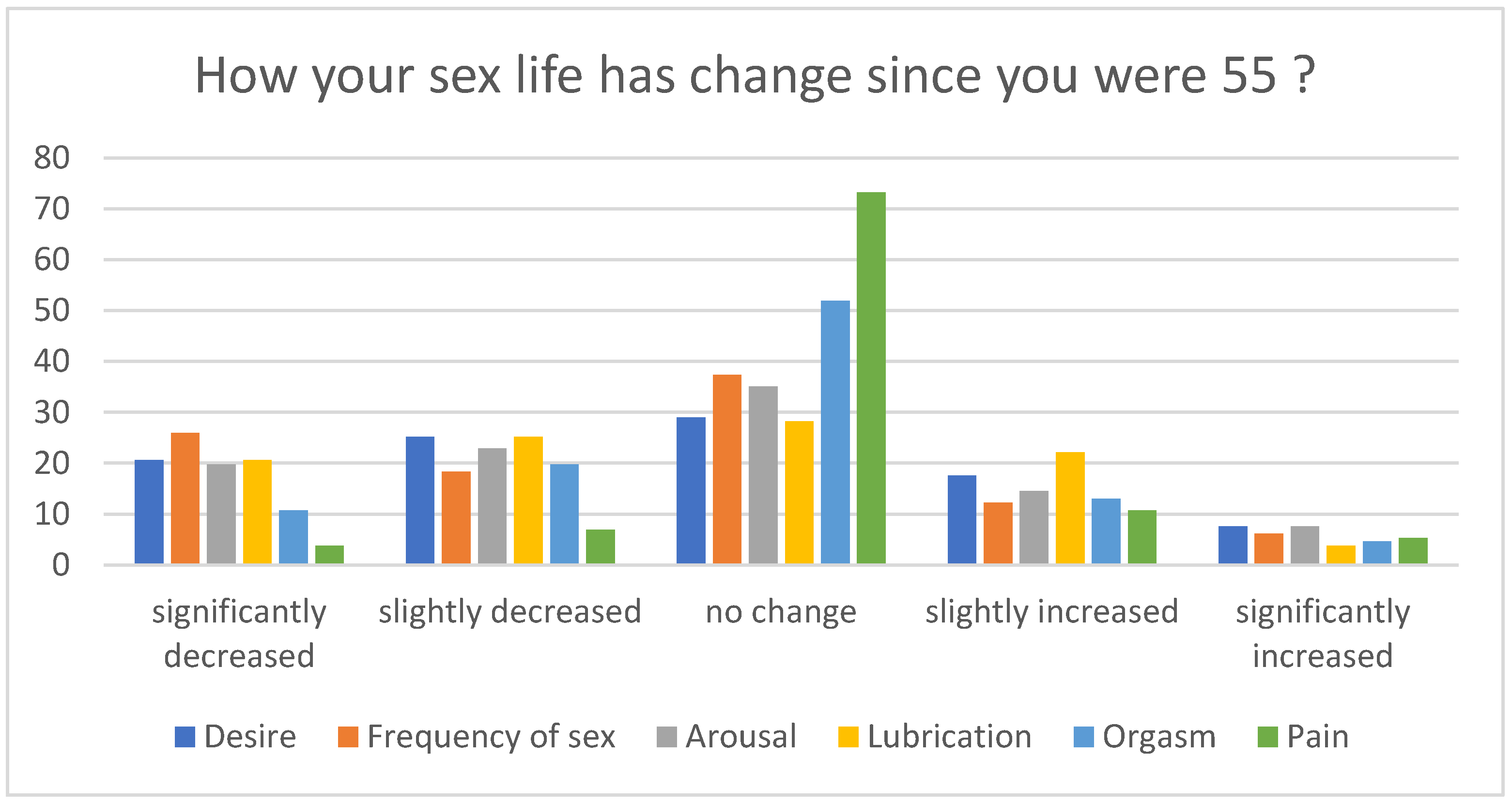

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Sexual Activity and Relationship

4.2. Sexual Performance and Satisfaction

4.3. Body Image and Sexual Excitation/Inhibition

4.4. Sexual Distress, Problems and Dysfunction

4.5. Risk Factors for FSD

4.6. Predictors of Sexual Function and Performance

4.7. Final Remarks on Sexual Function

4.8. Implications for Clinical Practice and Recommendations

4.9. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bell, S.; Reissing, E.D.; Henry, L.A.; VanZuylen, H. Sexual activity after 60: A systematic review of associated factors. Sex. Med. Rev. 2017, 5, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štulhofer, A.; Jurin, T.; Graham, C.; Janssen, E.; Træen, B. Emotional intimacy and sexual well-being in aging European couples: A cross-cultural mediation analysis. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simon, J.A.; Davis, S.R.; Althof, S.E.; Chedraui, P.; Clayton, A.H.; Kingsberg, S.A.; Nappi, R.E.; Parish, S.J.; Wolfman, W. Sexual well-being after menopause: An international menopause society white paper. Climacteric 2018, 21, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore-Gorszewska, G. ‘Why would I want sex now?’ A qualitative study on older women’s affirmative narratives on sexual inactivity in later life. Ageing Soc. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzer, J.; Platano, G.; Tschudin, S.; Alder, J. Sexual counseling in elderly couples. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 2027–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ševčíková, A.; Sedláková, T. The role of sexual activity from the perspective of older adults: A qualitative study. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štulhofer, A.; Hinchliff, S.; Jurin, T.; Hald, G.M.; Træen, B. Successful aging and changes in sexual interest and enjoyment among older european men and women. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 1393–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, H.; Starkings, R.M.L.; Fallowfield, L.J.; Menon, U.; Jacobs, I.J.; Jenkins, V.A.; Trialists, U. Sexual functioning in 4418 postmenopausal women participating in UKCTOCS: A qualitative free-text analysis. Menopause 2019, 26, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowosielski, K.; Sidorowicz, M. Sexual behaviors and function during menopausal transition-does menopausal hormonal therapy play a role? Menopause 2020, 28, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowosielski, K.; Wróbel, B.; Sioma-Markowska, U.; Poręba, R. Development and validation of the Polish version of the Female Sexual Function Index in the Polish population of females. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowosielski, K.; Wróbel, B.; Sioma-Markowska, U.; Poręba, R. Sexual dysfunction and distress—Development of a Polish version of the female sexual distress scale-revised. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowosielski, K.; Kurpisz, J.; Kowalczyk, R. Sexual inhibition and sexual excitation in a sample of Polish women. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowosielski, K.; Kurpisz, J.; Kowalczyk, R. Body image during sexual activity in the population of Polish adult women. Prz. Menopauzalny 2019, 18, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowosielski, K.; Kurpisz, J.; Kowalczyk, R. Sexual self-schema: A cognitive schema and its relationship to choice of contraceptive method among Polish women. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2019, 24, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowosielski, K.; Jankowski, K.S.; Kowalczyk, R.; Kurpisz, J.; Normantowicz-Zakrzewska, M.; Krasowska, A. Sexual self-schema scale for women-validation and psychometric properties of the polish version. Sex. Med. 2018, 6, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tremayne, P.; Norton, W. Sexuality and the older woman. Br. J. Nurs. 2017, 26, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Yang, L.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P.; Stubbs, B.; Jackson, S.E. Sexual activity is associated with greater enjoyment of life in older adults. Sex. Med. 2019, 7, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeleke, B.M.; Bell, R.J.; Billah, B.; Davis, S.R. Hypoactive sexual desire dysfunction in community-dwelling older women. Menopause 2017, 24, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Islam, R.M.; Bell, R.J.; Skiba, M.A.; Davis, S.R. Prevalence of low sexual desire with associated distress across the adult life span: An australian cross-sectional study. J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Træen, B.; Štulhofer, A.; Janssen, E.; Carvalheira, A.A.; Hald, G.M.; Lange, T.; Graham, C. Sexual activity and sexual satisfaction among older adults in four european countries. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skałacka, K.; Gerymski, R. Sexual activity and life satisfaction in older adults. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 19, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyverkens, E.; Dewitte, M.; Deschepper, E.; Corneillie, J.; Van der Bracht, L.; Van Regenmortel, D.; Van Cleempoel, K.; De Boose, N.; Prinssen, P.; T’Sjoen, G. YSEX? A replication study in different age groups. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buczak-Stec, E.; König, H.H.; Hajek, A. Sexual satisfaction of middle-aged and older adults: Longitudinal findings from a nationally representative sample. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarpour, S.; Simbar, M.; Tehrani, F.R. Sexual function in postmenopausal women and serum androgens: A review article. Int. J. Sex. Health 2019, 31, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ati, N.; Elati, Z.; Manitta, M.; Mnasser, A.; Zakhama, W.; Binous, M.Y. 498 Sexual dysfunction among postmenopausal Tunisian women. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, S305–S306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradskova, Y.; Kondakov, A.; Shevtsova, M. Post-socialist revolutions of intimacy: An introduction. Sex. Cult. 2018, 24, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jen, S. Sexuality of midlife and older women: A review of theory use. J. Women Aging 2018, 30, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, S.J.; Nicholson, A.A.; Stefanczyk, M.M.; Pieniak, M.; Martínez-Molina, J.; Pešout, O.; Binter, J.; Smela, P.; Scharnowski, F.; Steyrl, D. Securing your relationship: Quality of intimate relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic can be predicted by attachment style. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Residency | |

| Urban | 84.3 (156) |

| Rural | 15.7 (29) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 7.0 (13) |

| Secondary | 45.9 (85) |

| Higher | 47.3 (87) |

| Education | |

| Black-collar | 22.2 (41) |

| White-collar | 62.7 (116) |

| Unemployed | 7.0 (13) |

| Retired | 8.1 (15) |

| Smoking (Yes) | 23.2 (43) |

| Drugs (Yes) | 1.6 (3) |

| Alcohol (Yes) | 13.5 (25) |

| Religion | |

| Catholic | 76.8 (142) |

| Other | 7.0 (13) |

| Atheist | 16.2 (30) |

| Church attendances | |

| More than 1 time a week | 20.0 (37) |

| Once a month | 10.8 (20) |

| One or two times a year | 43.1 (80) |

| Never | 26.1 (48) |

| Participation in religious practices | 37.2 (69) |

| Being in RS (Yes) | 87.6 (162) |

| Sexual activity in last 3 months | 81.1 (150) |

| Sexual dysfunction in partner | 27.0 (50) |

| Watching erotic videos (Yes) | 39.5 (73) |

| Sexual abuse in childhood (Yes) | 9.2 (17) |

| Sexual behaviors | |

| WSW | 91.9 (170) |

| WSMW | 3.8 (7) |

| WSM | 2.2 (4) |

| Asexual | 2.2 (4) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 92.9 (172) |

| Homosexual | 2.7 (5) |

| Bisexual | 3.2 (6) |

| Asexual | 1.1 (2) |

| RSB (Yes) | 10.8 (20) |

| Regularity of menstruation (Yes) | 64.8 (120) |

| Pregnancies (Yes) | 90.8 (168) |

| MHT (Yes) | 35.1 (65) |

| HADS-Depression (Yes) | 33.5 (62) |

| HADS-Anxiety (Yes) | 38.4 (71) |

| Distress (FSDS-R) | 14.1 (26) |

| Distress (DSM-5) | 22.2 (41) |

| FSD (FSFI + FSDS-R scores) | 35.1 (65) |

| FSIAD | 13.0 (24) |

| FOD | 10.3 (19) |

| GPPPD | 4.9 (9) |

| FSD (DSM-5) | 16.2 (30) |

| Sexual problems—CSFQ | 33.3 (53) |

| Pleasure—CSFQ | 77.3 (143) |

| Desire/Frequency—CSFQ | 64.3 (119) |

| Desire/Interest—CSFQ | 64.3 (119) |

| Arousal/Excitement—CSFQ | 78.9 (146) |

| Orgasm/Completion—CSFQ | 49.1 (91) |

| Sexual self-Schema—positive | 43.3 (80) |

| Sexual self-Schema—negative | 4.5 (8) |

| Sexual self-Schema—Aschematic | 5.5 (8) |

| Sexual self-Schema—Co-schematic | 47.7 (88) |

| Variable | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67.82 | 56.00 | 79.37 | 3.08 |

| Religiosity | 2.93 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.13 |

| Nr of cigarettes a day | 2.12 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 4.89 |

| BMI | 26.51 | 13.74 | 41.15 | 4.62 |

| Weight self-perception | 3.59 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.74 |

| Age of first genital sex | 19.27 | 14.00 | 30.00 | 2.66 |

| Age of first oral sex | 21.37 | 13.00 | 40.00 | 5.54 |

| Age of first masturbation | 17.68 | 10.00 | 45.00 | 5.65 |

| Importance of sex | 3.31 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.83 |

| Satisfaction from sex life | 3.68 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.91 |

| Attitude toward sex | 4.11 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.76 |

| Duration of RS | 21.98 | 0.00 | 45.00 | 12.41 |

| Quality of RS | 4.12 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 1.14 |

| Satisfaction from a partner as a lover | 3.96 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 1.20 |

| Partner’s attitude toward sex | 4.19 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 0.92 |

| Vaginal sex/month | 6.27 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 8.97 |

| Cuddling/month | 4.90 | 0.00 | 40.00 | 6.78 |

| Anal sex/month | 0.68 | 0.00 | 15.00 | 2.13 |

| Oral sex/month | 2.26 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 4.07 |

| Mutual masturbation/month | 2.18 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 4.45 |

| Self-masturbation/month | 1.68 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 4.72 |

| Orgasm/month | 5.72 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 7.45 |

| Sex events/month | 6.03 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 9.72 |

| Sexual satisfaction/month | 5.95 | 0.00 | 90.00 | 8.75 |

| Nr of lifetime male sexual partners | 4.09 | 0.00 | 33.00 | 4.38 |

| Nr of lifetime female sexual partners | 0.49 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 2.53 |

| Nr of deliveries | 1.85 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 0.92 |

| HADS—Depression | 8.51 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 6.02 |

| HADS—Anxiety | 10.66 | 0.00 | 26.00 | 7.02 |

| FSFI—Desire | 4.03 | 1.20 | 6.00 | 1.28 |

| FSFI—Arousal | 3.42 | 1.20 | 7.20 | 1.56 |

| FSFS—Lubrication | 4.15 | 1.20 | 7.20 | 1.59 |

| FSFI—Orgasm | 3.68 | 1.20 | 7.20 | 1.47 |

| FSFI—Satisfaction | 2.72 | 1.20 | 6.00 | 1.24 |

| FSFI—Pain | 4.22 | 1.20 | 6.40 | 1.48 |

| FSFI—total score | 22.23 | 10.20 | 39.00 | 5.76 |

| FSDS-R—total score | 14.67 | 0.00 | 52.00 | 13.02 |

| BESAQ | 1.40 | 0.04 | 4.00 | 0.68 |

| CSFQ—pleasure | 3.30 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.08 |

| CSFQ—desire/frequency | 5.86 | 2.00 | 10.00 | 1.58 |

| CSFQ—desire/interest | 7.56 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 2.51 |

| CSFQ—arousal/excitement | 9.48 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 2.50 |

| CSFQ—orgasm/completion | 10.69 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 2.53 |

| CSFQ—total score | 43.71 | 15.00 | 69.00 | 8.87 |

| SES | 2.55 | 1.00 | 3.88 | 0.58 |

| SIS | 2.57 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.50 |

| WMRQ—Intimacy | 27.92 | 8.00 | 40.00 | 7.59 |

| WMRQ—Disappointment | 34.65 | 10.00 | 50.00 | 9.32 |

| WMRQ—Self-realization | 24.90 | 7.00 | 35.00 | 6.06 |

| WMRQ—Similarity | 25.03 | 7.00 | 35.00 | 6.15 |

| WMRQ—total score | 103.12 | 57.00 | 160.00 | 14.62 |

| MRS—total | 14.45 | 0.00 | 44.00 | 8.67 |

| MRS—psychological domain | 5.42 | 0.00 | 16.00 | 3.90 |

| MRS—somatic domain | 5.33 | 0.00 | 16.00 | 3.41 |

| MRS—urological domain | 3.71 | 0.00 | 12.00 | 2.83 |

| Variable (Mean) | FSD | No FSD | p | Distressing Sexual Concerns | No Concerns | p | Sexual Problems | No Sexual Problems | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of sex | 2.90 | 3.46 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 3.57 | 0.02 | 3.08 | 3.74 | 0.00 |

| Satisfaction from sex life | 3.20 | 3.88 | 0.00 | 2.75 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 3.47 | 4.09 | 0.00 |

| Quality of RS | 3.67 | 4.26 | 0.02 | 3.90 | 4.49 | 0.19 | 4.03 | 4.32 | 0.02 |

| Satisfaction from a partner as a lover | 3.37 | 4.10 | 0.01 | 3.10 | 4.41 | 0.00 | 3.70 | 4.37 | 0.01 |

| Partner’s attitude toward sex | 3.73 | 4.24 | 0.03 | 4.05 | 4.54 | 0.03 | 4.02 | 4.35 | 0.03 |

| Attitude towards sex | 3.63 | 4.25 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.41 | 0.10 | 3.87 | 4.50 | 0.00 |

| Vaginal sex/month | 3.96 | 6.53 | 0.00 | 3.67 | 6.56 | 0.02 | 5.35 | 7.22 | 0.00 |

| Anal sex/month | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.48 |

| Oral sex/month | 1.00 | 2.41 | 0.08 | 1.28 | 3.75 | 0.02 | 1.70 | 2.54 | 0.08 |

| Mutual masturbation/month | 1.89 | 2.04 | 0.64 | 2.11 | 4.11 | 0.05 | 1.62 | 2.58 | 0.64 |

| Self-masturbation/month | 2.68 | 1.27 | 0.62 | 6.00 | 1.26 | 0.75 | 1.52 | 1.50 | 0.62 |

| Orgasm/month | 3.29 | 6.09 | 0.00 | 8.61 | 7.50 | 0.73 | 4.03 | 7.58 | 0.00 |

| Sex events/month | 3.21 | 6.07 | 0.00 | 8.89 | 8.71 | 0.69 | 4.13 | 6.70 | 0.00 |

| Sexual satisfaction/month | 3.04 | 6.38 | 0.00 | 3.39 | 7.61 | 0.01 | 4.20 | 7.78 | 0.00 |

| Nr of lifetime male sexual partners | 2.86 | 3.90 | 0.18 | 3.25 | 6.11 | 0.01 | 3.10 | 4.24 | 0.18 |

| HADS—Depression | 11.07 | 7.82 | 0.00 | 15.45 | 15.97 | 0.91 | 7.88 | 8.57 | 0.00 |

| SES | 2.34 | 2.59 | 0.05 | 2.50 | 2.93 | 0.00 | 2.35 | 2.80 | 0.05 |

| SIS | 2.58 | 2.56 | 0.97 | 2.75 | 2.69 | 0.45 | 2.50 | 2.66 | 0.97 |

| WMRQ—Intimacy | 26.04 | 28.28 | 0.13 | 22.07 | 26.86 | 0.04 | 26.48 | 29.81 | 0.13 |

| WMRQ—Disappointment | 30.00 | 35.55 | 0.01 | 28.93 | 33.04 | 0.09 | 33.04 | 36.79 | 0.01 |

| WMRQ—Similarity | 23.50 | 25.32 | 0.09 | 20.14 | 24.11 | 0.05 | 23.45 | 27.09 | 0.09 |

| WMRQ—total score | 104.35 | 102.89 | 0.43 | 92.77 | 100.04 | 0.16 | 101.19 | 105.67 | 0.43 |

| MRS—total | 22.15 | 12.89 | 0.00 | 15.27 | 16.10 | 1.00 | 15.57 | 12.97 | 0.00 |

| MRS—psychological domain | 8.85 | 4.72 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 6.66 | 0.81 | 5.78 | 4.92 | 0.00 |

| MRS—somatic domain | 7.81 | 4.83 | 0.00 | 5.60 | 5.55 | 0.71 | 5.65 | 4.91 | 0.00 |

| MRS—urological domain | 5.50 | 3.34 | 0.00 | 3.67 | 3.90 | 0.90 | 4.14 | 3.14 | 0.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nowosielski, K. Predictors of Sexual Function and Performance in Young- and Middle-Old Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074207

Nowosielski K. Predictors of Sexual Function and Performance in Young- and Middle-Old Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074207

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowosielski, Krzysztof. 2022. "Predictors of Sexual Function and Performance in Young- and Middle-Old Women" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074207

APA StyleNowosielski, K. (2022). Predictors of Sexual Function and Performance in Young- and Middle-Old Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074207