1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a tremendous impact on the everyday life and mental health of children and adolescents. The pandemic has caused stress, anxiety, depression, and increased risky or social behavioral problems [

1,

2], and the rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in young people have risen [

3,

4,

5]. Nevertheless, the findings are not always consistent: studies conducted shortly after the first lockdown (spring/summer 2020) often report a decrease in psychopathological symptoms or in treatment demand (e.g., [

6]), but with the publication of more recent studies, the need to take into account the dynamics of the pandemic and the precise timing of research is becoming evident. According to a recent meta-analysis, the prevalence of clinically elevated anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents has increased in course of the pandemic, with a higher symptom prevalence in studies conducted at the end of the first year than at the beginning [

7]. Ordinarily, rising prevalence rates of mental health problems in children and young people should be reflected in higher admission rates to mental health services. Studies are only just beginning to investigate whether this was also the case under pandemic conditions, where possible treatment barriers include social distancing rules, hesitancy to seek help due to fear of infection, and increased institutional problems. A recent European survey among the heads of university departments for child and adolescent psychiatry, encompassing 64 contributions from 22 European countries, including Switzerland, reported a decrease in referrals in April/May 2020 (60% of responses) and a marked increase in February/March 2021 (90.5% of responses). For spring 2020, only a small proportion of respondents (generally less than 30%) reported an increased prevalence occurrence of certain disorders, such as anxiety or obsessive compulsive disorders. By contrast, for February/March 2021, the vast majority of respondents reported increased numbers of cases with anxiety disorders (70%), depression (>60%), eating disorders (>60%), and suicidal crises (>80%) [

8]. Data from the Republic of Ireland [

9] indicate that referrals to specialized child and adolescent mental health services dropped by around 10% up to August 2020 and then steadily increased up to December 2020, reaching 180% compared to previous years, with double the number of outpatient appointments compared to previous years. A recent qualitative U.S. study reported that services suspected an increased need for mental health care for children and young people during the pandemic, but that staff shortages and decreased service capacity under COVID-19 conditions made it difficult to estimate the true amount [

10]. Another U.S. study analyzed admission to a child and adolescent psychiatry inpatient unit between March 2020 and January 2021 and found that 53% of admissions due to adolescent psychiatric crises were related to COVID-19 stressors, although the overall number of admissions had slightly decreased [

11].

As another effect of the pandemic, the implementation of telemental health increased, although a number of barriers were identified, such as unclear funding for services, limited internet access, family/client reluctance, or problems linked to online sessions with younger children [

10]. A Canadian survey of mental health professionals working in services for mentally ill children and adolescents found that 71% of respondents began to use virtual care during pandemic. The majority of respondents (61%) indicated that virtual care was more effective with adolescents than with children. Most professionals found that telemental health was more tiring and demanded more concentration than in-person sessions and reported that certain relevant non-verbal aspects of the interaction were lacking [

12]. Other possible disadvantages of telemental health were the uncertain privacy and the higher attentional demands, which were often too difficult for younger children [

13].

The present study aims to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s and adolescents’ mental health, on the treatment for children and adolescents with mental disorders, and on care service providers during the first year of pandemic from the perspective of youth mental health professionals. In the present analysis, we focus on treatment supply, treatment conditions, and the mental health professionals’ situation during COVID-19. More specifically, we hypothesize that the professionals would report an increased demand for treatment in the long term and extended waiting times until the initiation of treatment in children and adolescents. In addition, we seek to assess the burden and challenges experienced by mental health professionals working with children and adolescents in Switzerland during the pandemic. Since the pandemic made the delivery of in-person psychotherapy difficult or impossible, we expect a sizable number of mental health professionals to recur to telemental health, which, before the pandemic, was very rarely used in child and adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy in Switzerland.

4. Discussion

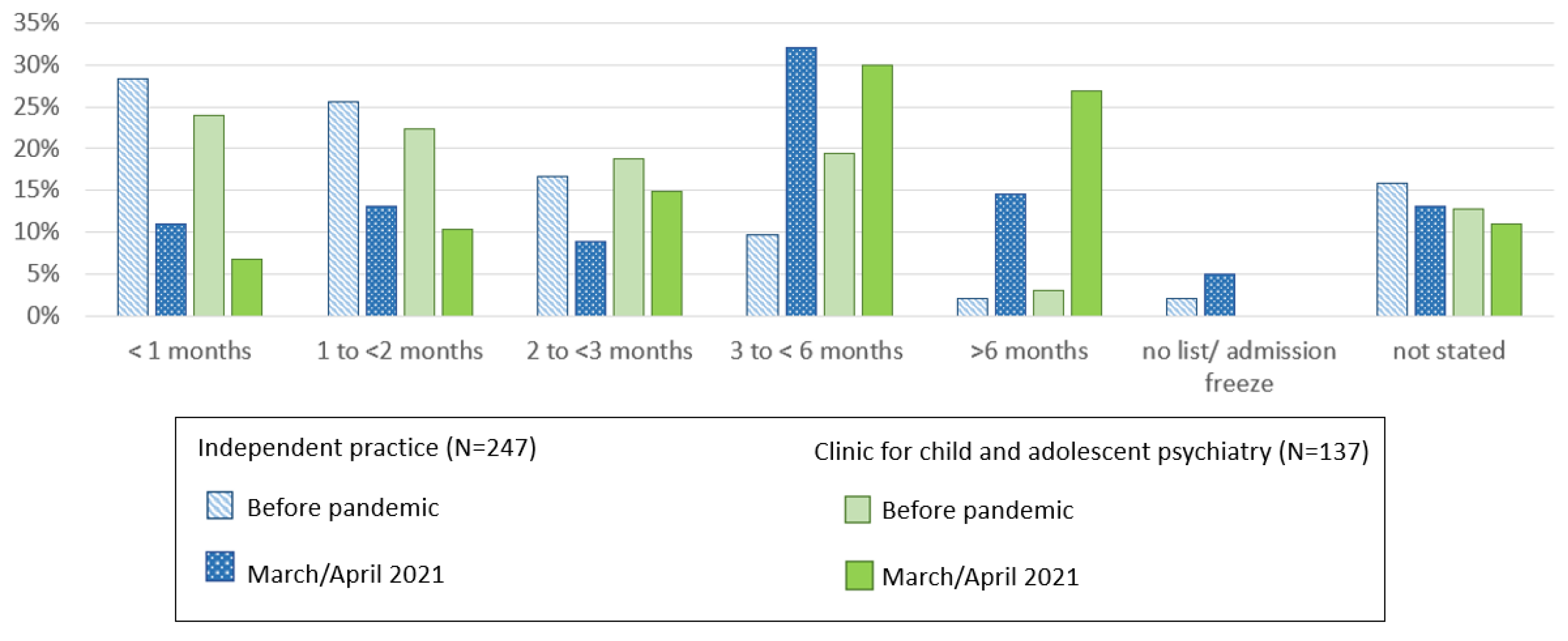

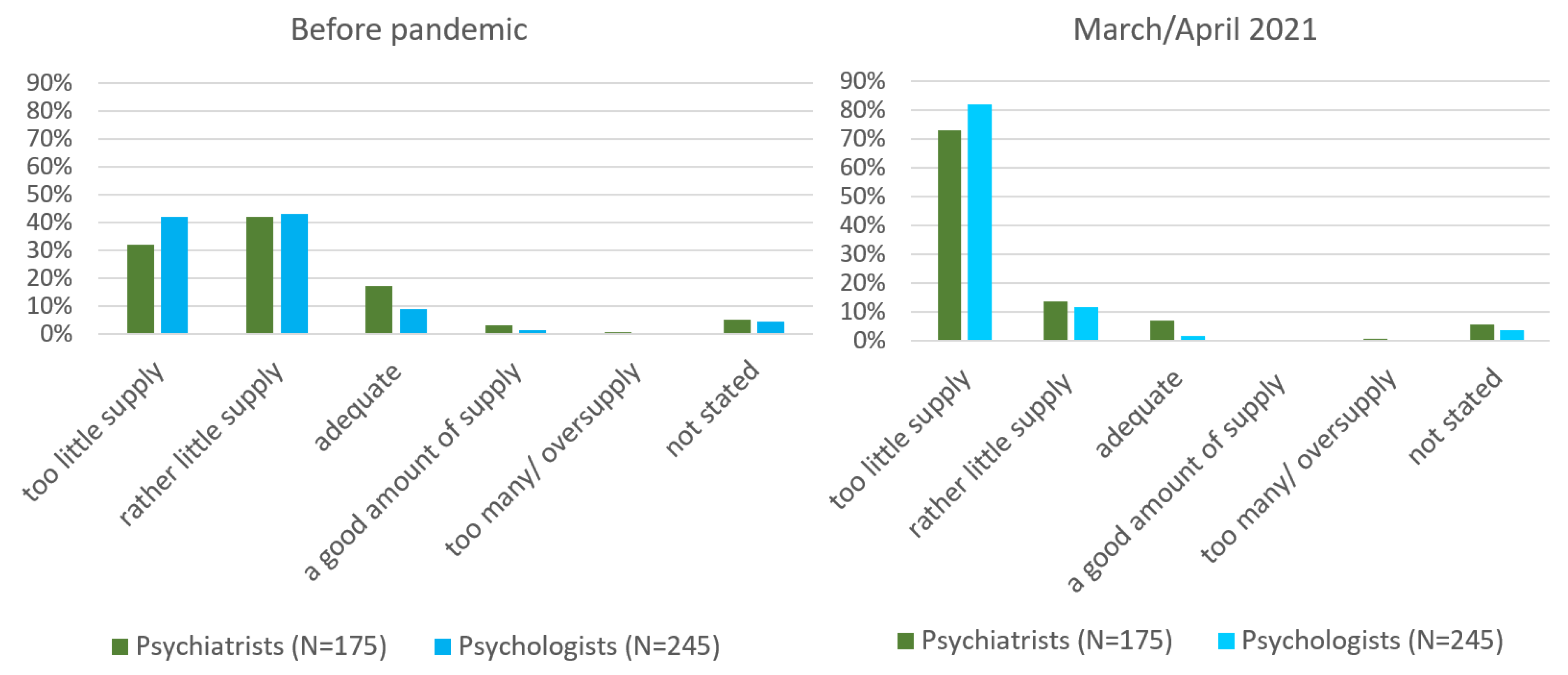

For the first year of the pandemic, youth mental health professionals in Switzerland reported an initial period of decreased demand for treatment during the COVID-19 lockdown in spring 2020, followed by a successive, slight increase in summer 2020, a marked increase in autumn 2020 (“2nd wave”) and a peak in demand in the first quarter of 2021. This peak came with a considerably increased waiting time for the initiation of treatment and a general shortfall in treatment supply for children and adolescents with mental health problems. Notably, as the two professional groups, psychiatrists and psychologists, did not differ in their evaluation of insufficient treatment supply, these findings cannot be explained by specific professional policies. It is important to point out that the increased need for treatment peaked with a certain delay to the course of the pandemic. In Switzerland, the lockdown was confined to a relatively short period at the beginning of the pandemic and without a strict curfew, and its effects on the well-being of children and adolescents with mental health problems were comparatively mild [

18]. For many young people, this period may have represented a protected situation of general deceleration, spent with one’s core family, and with fewer academic or social pressures. As indicated by mental health professionals, some patients did not show up for therapy as planned, possibly for reasons of social distancing or because the symptoms of some patients with pre-existing mental disorders, such as social anxiety, may have temporarily improved during the lockdown (e.g., see [

15,

19]). In addition, during the summer months of 2020, the incidence rates of COVID-19 in Switzerland were low, and there was a general optimism that the pandemic might soon be over. The observation of a delayed but alarming increase in treatment demand up to January/February/March 2021 was confirmed by the analysis of electronic patient records prior and during the COVID-19 pandemic from the emergency outpatient facility of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich [

20]. These findings also correspond to reports from some other European countries [

8,

9], although data on the number of outpatient treatments are not consistent. In a survey of European clinics for child and adolescent psychiatry, respondents more often indicated that the number of outpatients decreased (N = 21) rather than increased (N = 10) in February/March 2021, compared to before the pandemic [

8]. This may partly be related to national differences in the organization of treatment supply for children and adolescents with mental health problems.

Regarding their own situation, most respondents indicated that their workload peaked in January/February/March 2021, which is not surprising as it parallels increased demands for treatment. The unusual accumulation of crisis/emergency interventions and the fear of being unable to retain the quality of treatment due to work overload were among the most stressful worries. It was also reported that the triage of whom to accept as an emergency and whom to put on a waiting list was extremely burdensome. In contrast, fear for one’s own health or the health of one’s family members was seldom indicated at this stage of the pandemic, although several respondents mentioned an increasing depletion of their own resources. An increased risk of burnout or psychological distress for mental health professionals under COVID-19 was described [

21,

22], but resilience seems to outweigh burnout tendencies and fatigue in this population [

23].

The percentage of almost 70% of respondents who administered online therapies at some time during the pandemic was remarkable, as the use of telemental health, with exception of phone consultations, seemed very uncommon in child and adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy in Switzerland before COVID-19. This percentage of almost 70% equals that reported in other surveys with mental health professionals during the pandemic (e.g., 70% of users in a survey of U.S. psychologists [

24]). The proportion of current online therapies (March/April 2021), however, was relatively low. After a successful shift from in-person to digital therapy, which became necessary under COVID-19, most mental health professionals obviously preferred to return to onsite contacts as soon as possible. Most respondents also indicated that they intended to use telemental health only from time to time in the future for clinical routine purposes, even if all technical or other problems were resolved. Compared to online therapy with adults, the use of telemental health in children and adolescents may present several limitations. Treatment is often less verbal with younger children than with adolescents, and often includes physical activities (e.g., acting together or playing), which cannot be realized via telemental health. In the case of adolescents, privacy aspects may be less well protected (e.g., if parents or siblings enter the room during the session). Telemental health with suicidal adolescent patients may constitute a risk [

12] and should be replaced with on-site contacts. On the other hand, an advantage of telemental health, as mentioned by some respondents, lies in the possibility to bring all involved persons together more easily for counseling, e.g., mother, father, school teacher, or special education teacher. The fact that over 60% of respondents working in institutions identified technical problems as barriers to the use of telemental health leaves room for improvement on the institutional IT level. Nevertheless, the large majority of respondents would only prefer to resort to telemental health occasionally in their daily routines.

Taken together, mental health professionals reported an alarming increase in treatment demand, a large increase in the waiting time before the initiation of treatments, and an increasing work overload, all peaking after one year of the pandemic, in January/February/March 2021. Despite the fact that Switzerland, in comparison to other European countries, only had a short phase of lockdown and school closures, children and adolescents had to face an increase in mental health problems. Health care professionals warned that the lack of school routine and other support provided in the school context might particularly affect children and adolescents with pre-existing mental illness or vulnerabilities [

25], and it has been shown that, more generally, school closure and home confinement led to psychological consequences, such as fear, anxiety, restlessness, irritability, and others [

26]. However, keeping the schools open is obviously not sufficient to guarantee good mental health.

4.1. Implications of the Study and Future Directions

The results of the present study indicate that the shortage of mental health care and services of children and adolescents already existed before the pandemic. This gap has considerably widened since then, due to an alarming increase in the need for treatment during the pandemic. While it was imperative to take measures to protect vulnerable groups during the pandemic, too little attention was paid to other vulnerable groups, namely children and adolescents at risk of mental disorders or with pre-existing mental problems. To counteract this problematic situation and to prevent similar developments in the future, actions have to be taken on various levels.

In the short and medium term, psychiatric and psychotherapeutic care in clinics and practices should be expanded even further to increase treatment capacity. Being forced to perform a triage of patients due to limited resources, as described by many professionals in this survey, is challenging and stressful. It is professionally and ethically difficult to decide which one of two patients may be more in need of treatment, especially as seemingly less acute cases can turn soon into emergencies if they are not treated in time. A more systematic networking of mental health professionals including those in independent practice and a system to report available outpatient and inpatient therapy places could be helpful in times of crises, but, of course only, if free capacities are still available. At the same time, services must be adapted more specifically to the needs of children and adolescents, for example, with the expansion of low threshold access for brief crisis interventions, to home treatment services with a focus on the support of families and on the environment of the child or adolescent. It should be avoided that adolescents in acute crisis have to be triaged into adult psychiatry due to a shortage of inpatient treatment places in child and adolescent psychiatry.

In the long term, the focus should be placed on primary and secondary prevention. All professionals working with children and adolescents can make an important contribution here, e.g., teachers, pediatricians and general practitioners or school social workers and counselors. Professional training for the strengthening of mental health and early recognition of mental disorders to prevent psychiatric disorders and chronicity is recommended. Programs to ensure psychological stability or promote resilience, such as sports or recreational programs, should be expanded and made accessible to all—in particular, to socially disadvantaged families.

In the event of a recurrent coronavirus crisis, professionals should be better prepared to offer alternative treatment options to maintain therapeutic/psychiatric care. Access to telemedicine should be offered early and facilitated, both for the patients and for mental health professionals, without having to struggle with technical difficulties or barriers to financing. However, only ensuring funding for online therapies does not solve the problem with younger or suicidal patients not eligible for telemental health.

Children’s and adolescents’ mental health—especially in times of crises—should be treated as a priority. Child and adolescent psychiatrists or psychologist, and not just adult psychiatrists, should be members of advisory bodies to the government. As far as we know, the situation in child and adolescent psychiatry and the impact of the pandemic on children’s and adolescents’ mental health differed considerably from those reported for adult psychiatry in Switzerland.

Finally, better recognition of the work of mental health professionals and better protection in times of pandemic is urgently needed, especially in mental health care for children and adolescents. In normal times, this could mean a remuneration comparable to that of other medical disciplines, during pandemic, e.g., a prioritization of vaccination, just as for other health professions.

Further research should analyze whether or to what extent countries with more liberal COVID-19 policies still have an advantage regarding the mental health outcomes of their youth, compared to countries with strict home confinement measures and prolonged school closures. Keeping the schools open during the pandemic was probably the best alternative for all concerned, but obviously not sufficient to guarantee good mental health for children and adolescents at risk.

4.2. Limitations

The study presents several limitations. All responses were explicitly based on subjective impressions of mental health care professionals, not on objective data, and may thus be biased. In addition, information on pre-COVID-19 conditions and the different periods of the pandemic were collected retrospectively and may be subject to cognitive bias. Information on the age and gender of participants, which might influence the responses, was not collected. Additionally, we did not assess the use of pre-pandemic telemental health. The response rate was relatively low, albeit satisfactory, considering the difficult context of an anonymous survey for a group of people with very little time and work overload. The proportion of professions and language regions of the participants seems to roughly be in agreement with the proportion of mental health care professionals in this domain, to the best of our knowledge, but the representativeness of the study remains questionable. Although the survey items were clearly aimed at the changes brought about by the pandemic, other causes for the reported changes cannot completely be ruled out. Finally, we focused here exclusively on the situation of mental health professionals and did not discuss the reasons or the nature of the increased demand for treatment.