A Scoping Review of Climate Change, Climate-Related Disasters, and Mental Disorders among Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

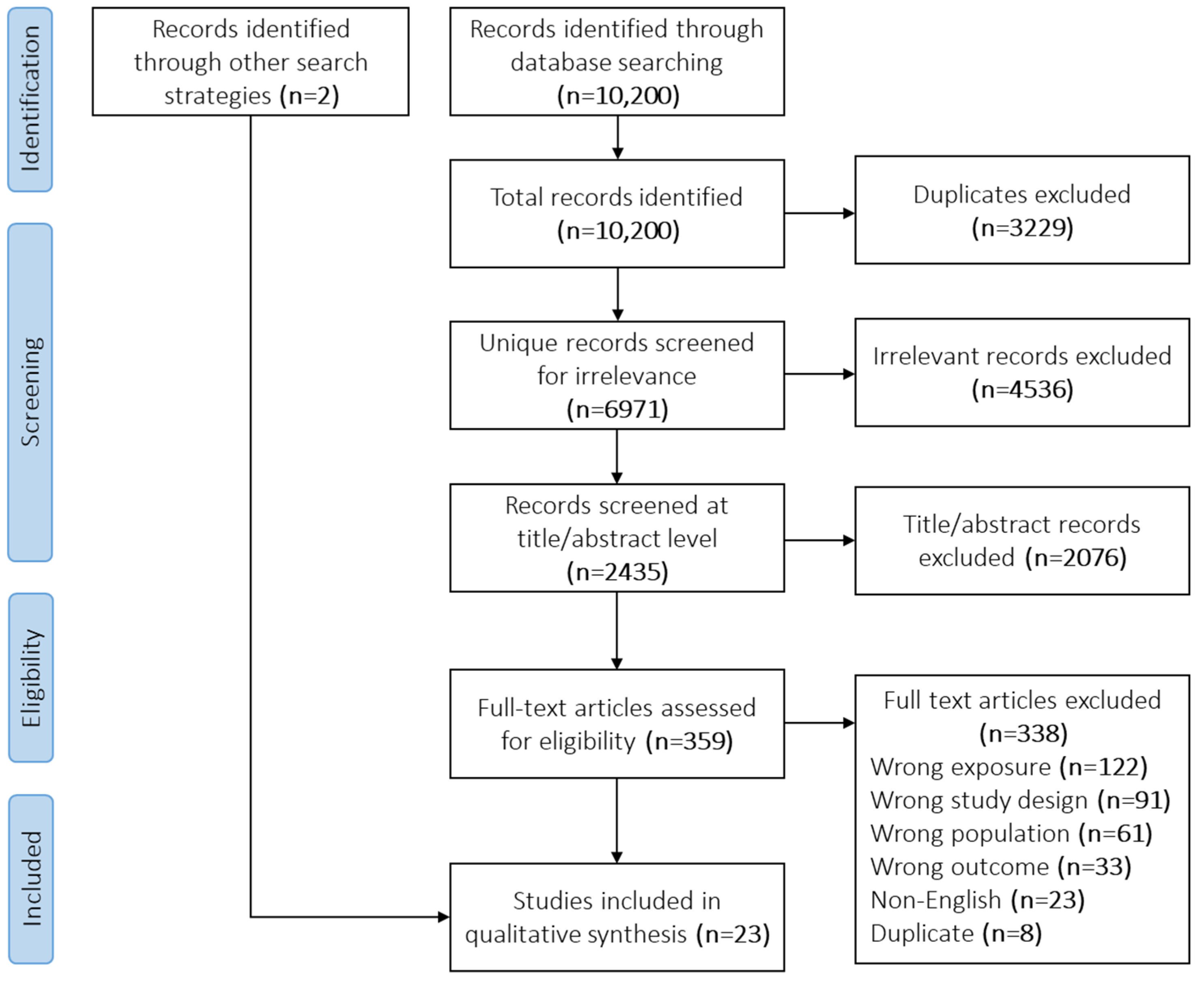

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

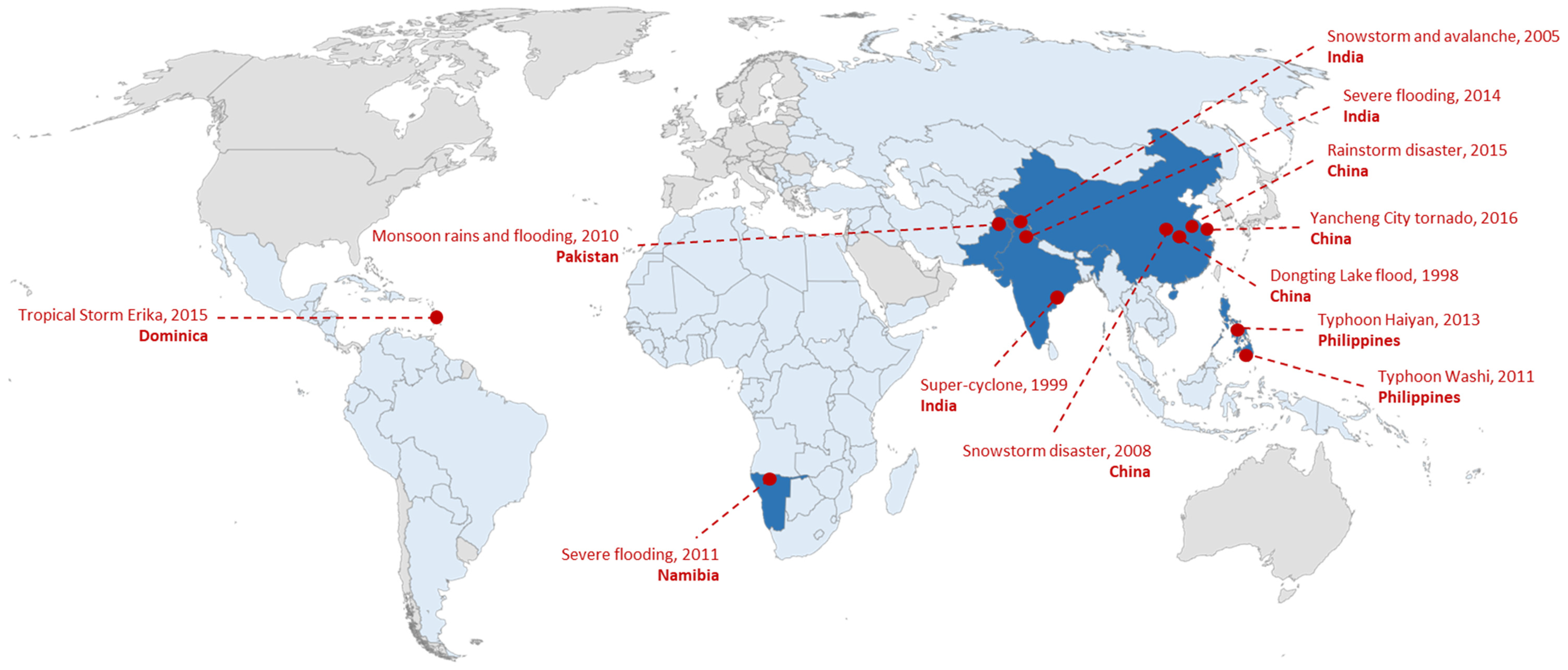

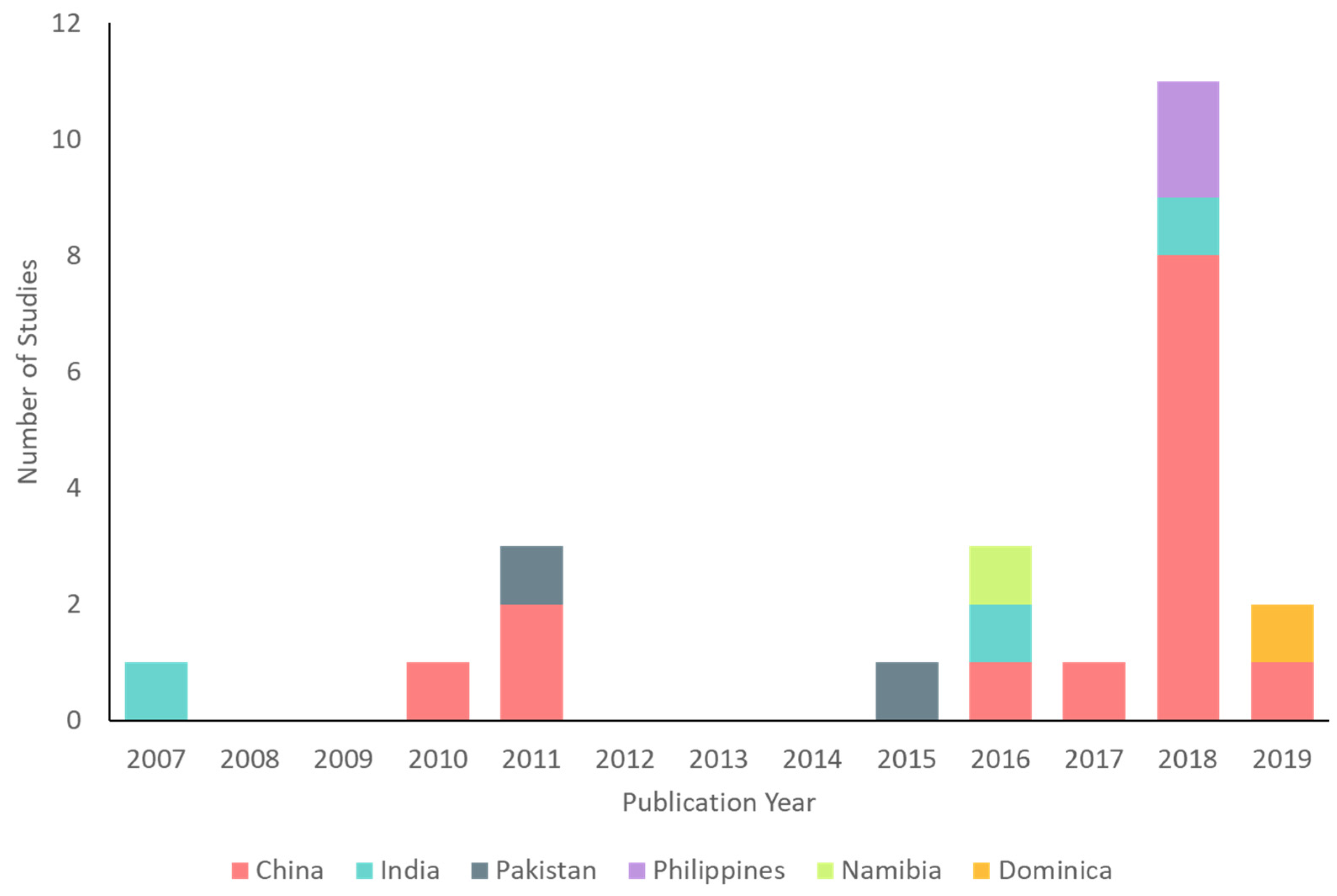

3.1. China

3.2. India

3.3. Pakistan

3.4. Philippines

3.5. Namibia

3.6. Dominica

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Meteorological Organization. State of the Global Climate 2020; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M.; et al. Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Beagley, J.; Belesova, K.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; et al. The 2020 report of the Lancet countdown on health and climate change: Responding to converging crises. Lancet 2021, 397, 129–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, F.; Ali, S.; Benmarhnia, T.; Pearl, M.; Massazza, A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Scott, J.G. Climate change and mental health: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, A.; Black, J.; Jones, M.; Wilson, L.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Astell-Burt, T.; Black, D. Flooding and mental health: A systematic mapping review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shultz, J.M.; Rechkemmer, A.; Rai, A.; McManus, K.T. Public health and mental health implications of environmentally induced forced migration. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.; Hess, T.; Daccache, A.; Wheeler, T. Climate change impacts on crop productivity in Africa and South Asia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 034032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, A. Natural disasters and the insurance industry. In The Economic Impacts of Natural Disasters; Guha-Sapir, D., Santos, I., Borde, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 128–153. ISBN 978-0-19-984193-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rathod, S.; Pinninti, N.; Irfan, M.; Gorczynski, P.; Rathod, P.; Gega, L.; Naeem, F. Mental health service provision in low- and middle-income countries. Health Serv. Insights 2017, 10, 1178632917694350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saraceno, B.; van Ommeren, M.; Batniji, R.; Cohen, A.; Gureje, O.; Mahoney, J.; Sridhar, D.; Underhill, C. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2007, 370, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rataj, E.; Kunzweiler, K.; Garthus-Niegel, S. Extreme weather events in developing countries and related injuries and mental health disorders—A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beaglehole, B.; Mulder, R.T.; Frampton, C.M.; Boden, J.M.; Newton-Howes, G.; Bell, C.J. Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharpe, I.; Davison, C.M. Climate change, climate-related disasters and mental disorder in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. The Climate Crisis is a Child Rights Crisis: Introducing the Children’s Climate Risk Index; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield, P.E.; Landrigan, P.J. Global climate change and children’s health: Threats and strategies for prevention. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Oliva, P. Implications of climate change for children in developing countries. Future Child. 2016, 26, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.D.; Sourander, A.; Duarte, C.S.; Niemelä, S.; Multimäki, P.; Nikolakaros, G.; Helenius, H.; Piha, J.; Kumpulainen, K.; Moilanen, I.; et al. Do mental health problems in childhood predict chronic physical conditions among males in early adulthood? Evidence from a community-based prospective study. Psychol. Med. 2009, 39, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faravelli, C.; Sauro, C.L.; Godini, L.; Lelli, L.; Benni, L.; Pietrini, F.; Lazzeretti, L.; Talamba, G.A.; Fioravanti, G.; Ricca, V. Childhood stressful events, HPA axis and anxiety disorders. World J. Psychiatry 2012, 2, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersky, J.P.; Topitzes, J.; Reynolds, A.J. Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: A cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miettunen, J.; Murray, G.K.; Jones, P.B.; Mäki, P.; Ebeling, H.; Taanila, A.; Joukamaa, M.; Savolainen, J.; Törmänen, S.; Järvelin, M.-R.; et al. Longitudinal associations between childhood and adulthood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology and adolescent substance use. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, B.W.; Lange, S.; Rogelj, J.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Gudmundsson, L.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Andrijevic, M.; Frieler, K.; Emanuel, K.; Geiger, T.; et al. Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes. Science 2021, 374, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.E.L.; Sanson, A.V.; van Hoorn, J. The psychological effects of climate change on children. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, V.; von Hirschhausen, E.; Fegert, J.M. Report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: Implications for the mental health policy of children and adolescents in Europe—A scoping review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, S. The implications of climate change for children in lower-income countries. Child. Youth Environ. 2008, 18, 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Helldén, D.; Andersson, C.; Nilsson, M.; Ebi, K.L.; Friberg, P.; Alfvén, T. Climate change and child health: A scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e164–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Degenhardt, L.; Feigin, V.; Vos, T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: An analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grimshaw, J. A Guide to Knowledge Synthesis: A Knowledge Synthesis Chapter; Canadian Institutes for Health Research: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2010; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-557-2.

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Middleton, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Wright, C.J.; Harper, S.L. Indigenous mental health in a changing climate: A systematic scoping review of the global literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, K.; Stapleton, J.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Hanning, R.M.; Leatherdale, S.T. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sitwat, A.; Asad, S.; Yousaf, A. Psychopathology, psychiatric symptoms and their demographic correlates in female adolescents flood victims. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. 2015, 25, 886–890. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.; Liu, A.; Zhou, J.; Wen, S.; Li, S.; Yang, T.; Li, X.; Huang, X.; Abuaku, B.; Tan, H. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder and preflood behavioral characteristics among children aged 7–15 years in Hunan, China. Med. Princ. Pract. Int. J. Kuwait Univ. Health Sci. Cent. 2011, 20, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Bukhari, T.; Munir, N. The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among flood affected school children in Pakistan. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. Inst. Interdiscip. Bus. Res. UK 2011, 3, 445–452. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Z. Longitudinal cross-lagged relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in adolescents following the Yancheng tornado in China. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowhan, A.; Margoob, M.A.; Mansoor, I.; Sakral, A. Psychiatric morbidity in children and adolescent survivors of a snowstorm disaster in South Kashmir, India. Br. J. Med. Pract. 2016, 9, a902. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, N.; Mohapatra, P.K.; Nayak, K.C.; Pattanaik, P.; Swain, S.P.; Kar, H.C. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents one year after a super-cyclone in Orissa, India: Exploring cross-cultural validity and vulnerability factors. BMC Psychiatry 2007, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, D.; Yin, H.; Xu, S.; Zhao, Y. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress reactions among Chinese students following exposure to a snowstorm disaster. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hassan, F.U.; Singh, G.; Sekar, K. Children’s reactions to flood disaster in Kashmir. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2018, 40, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Zhen, R.; Yao, B.; Zhou, X.; Yu, D. The role of perceived severity of disaster, rumination, and trait resilience in the relationship between rainstorm-related experiences and PTSD amongst Chinese adolescents following rainstorm disasters. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tavernier, R.; Fernandez, L.; Peters, R.K.; Adrien, T.V.; Conte, L.; Sinfield, E. Sleep problems and religious coping as possible mediators of the association between tropical storm exposure and psychological functioning among emerging adults in Dominica. Traumatology 2019, 25, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Yuan, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, W. Dispositional mindfulness mediates the relationships of parental attachment to posttraumatic stress disorder and academic burnout in adolescents following the Yancheng tornado. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 9, 1472989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- An, Y.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, N.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, F. Longitudinal cross-lagged relationships between mindfulness, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and posttraumatic growth in adolescents following the Yancheng tornado in China. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 266, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, X.; Tan, H.; Liu, A.; Zhou, J.; Yang, T. A study on the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder in flood victim parents and children in Hunan, China. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yuan, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; An, Y. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD and depression among adolescent victims of the summer 2016 tornado in Yancheng City. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Ding, X.; Goh, P.H.; An, Y. Dispositional mindfulness moderates the relationship between depression and posttraumatic growth in Chinese adolescents following a tornado. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 127, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Fu, G.; An, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhou, Y. Mindfulness, posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, and social functioning impairment in Chinese adolescents following a tornado: Mediation of posttraumatic cognitive change. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; An, Y. Dispositional mindfulness, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and academic burnout in chinese adolescents following a tornado: The role of mediation through regulatory emotional self-efficacy. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2018, 27, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; An, Y. Resilience, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and posttraumatic growth in Chinese adolescents after a tornado: The role of mediation through perceived social support. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Yuan, G.; An, Y. The relationship between posttraumatic cognitive change, posttraumatic stress disorder, and posttraumatic growth among Chinese adolescents after the Yancheng tornado: The mediating effect of rumination. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhen, R.; Quan, L.; Yao, B.; Zhou, X. Understanding the relationship between rainstorm-related experiences and PTSD among Chinese adolescents after rainstorm disaster: The roles of rumination and social support. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mordeno, I.G.; Galela, D.S.; Nalipay, M.J.N.; Cue, M.P. Centrality of event and mental health outcomes in child and adolescent natural disaster survivors. Span. J. Psychol. 2018, 21, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalipay, M.J.N.; Mordeno, I.G. Positive metacognitions and meta-emotions as predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in survivors of a natural disaster. J. Loss Trauma 2018, 23, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taukeni, S.; Chitiyo, G.; Chitiyo, M.; Asino, I.; Shipena, G. Post-traumatic stress disorder amongst children aged 8–18 affected by the 2011 northern-Namibia floods. Jamba Potchefstroom S. Afr. 2016, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Y.; Chen, X. The 1998 flood on the Yangtze, China. Nat. Hazards 2000, 22, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The impact of event scale—Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. ISBN 978-1-57230-162-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lagmay, A.M.F.; Agaton, R.P.; Bahala, M.A.C.; Briones, J.B.L.T.; Cabacaba, K.M.C.; Caro, C.V.C.; Dasallas, L.L.; Gonzalo, L.A.L.; Ladiero, C.N.; Lapidez, J.P.; et al. Devastating storm surges of typhoon Haiyan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Xu, Z.; Sheffield, P.E.; Hu, W.; Su, H.; Yu, W.; Qi, X.; Tong, S. Climate change and children’s health—A call for research on what works to protect children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3298–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mukherji, A.; Ganapati, N.; Rahill, G. Expecting the unexpected: Field research in post-disaster settings. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 805–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstadter, A.B.; Acierno, R.; Richardson, L.K.; Kilpatrick, D.G.; Gros, D.F.; Gaboury, M.T.; Tran, T.L.; Trung, L.T.; Tam, N.T.; Tuan, T.; et al. Posttyphoon prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder in a Vietnamese sample. J. Trauma. Stress 2009, 22, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wind, T.R.; Joshi, P.C.; Kleber, R.J.; Komproe, I.H. The impact of recurrent disasters on mental health: A study on seasonal floods in northern India. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2013, 28, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N. Psychological impact of disasters on children: Review of assessment and interventions. World J. Pediatr. WJP 2009, 5, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, G.-C.; Ryan, G.; Silva, M.J.D. Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Nitiéma, P.; Tucker, P.; Newman, E. Early child disaster mental health interventions: A review of the empirical evidence. Child Youth Care Forum 2017, 46, 621–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, A. Climate change and mental health following flood disasters in developing countries, a review of the epidemiological literature: What do we know, what is being recommended? Australas. J. Disaster Trauma Stud. 2012, 2012-1, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Suldo, S.M.; Shaffer, E.J. Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 37, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antaramian, S.P.; Huebner, E.S.; Hills, K.J.; Valois, R.F. A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 80, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | - Child focused (study population with mean age 18 years and under) - Study population located entirely in low- and middle-income countries at time of exposure (may be located in more than one) 1 | - Adult focused (study population with mean age over 18 years) - Any part of the study population located in high-income countries |

| Intervention (Exposure) | - Climate-related disaster exposure (see Table S1 for list of climate-related disasters) OR climate change-related exposure (as identified by the study author) 2 | |

| Comparison | - Any | |

| Outcome | - Mental disorders (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, acute stress, substance use and addiction, bipolar, schizophrenia, suicidal behavior, non-suicidal self-injury) evaluated based on DSM or ICD symptoms | - Mental disorders not evaluated based on DSM or ICD symptoms - Study only measures positive mental health |

| Study Design | Any type of empirical literature, including - Journal articles (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) - Grey literature (conference proceedings, dissertations, government and organization documents, policy briefs) | - Narrative reviews, syntheses (scoping reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, etc.), commentaries, editorials, expert opinions - Validation studies - Non-English language - Date of publication before 2007 3 |

| Study ID | Design | Sample Size and Population | Sampling Method | Climate-Related Disaster Exposure(s) | Mental Disorder Outcome(s) | Outcome Measurement Tool(s) | Post-Exposure Follow-Up Length | Main Findings (on the Association between Climate-Related Disasters and Mental Disorders) | Mental Disorder Prevalence Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China (n = 14) | |||||||||

| An-2019 (same baseline sample as Xu 2018a) [39] | Prospective cohort | 154 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD, depression | CPSS, CES-DC (self-reported surveys) | 6 (T1), 9 (T2), and 12 (T3) months | Post-tornado PTSD and depression: 55.84% and 56.49% at T1, 50.0% and 65.58% at T2, 47.40% and 66.01% at T3; PTSD at T1 significantly predicted depression at T2 (p < 0.001) and PTSD at T2 significantly predicted depression at T3 | |

| An-2018a (sample related to Xu-2018a) [46] | Cross-sectional | 443 junior high school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD | CPSS (self-reported survey) | 12 months | ||

| An-2018b (same baseline sample as Xu 2018a) [47] | Prospective cohort | 204 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD | CPSS (self-reported survey) | 6 and 9 months | ||

| Li-2010 [48] | Cross-sectional | 4327 children aged 7–15 and their parents | Multistage cluster random sampling | Flood (Dongting Lake) | PTSD | DSM-IV criteria (interview) | 18 months | Presence of PTSD was significantly greater among children who experienced flash or drainage problem flooding, experienced moderate (25–49% of total village area) or severe (≥50% of total village area) flooding, were dropped into water, were trapped in water, had a serious injury, had seriously injured relatives, witnessed somebody drown, had death of a family member or friend, were trapped in water near a dead body, had previous flood experience, were separated from family members, had teachers or classmates drown, had class suspended, had the following school semester postponed, and had parents with PTSD (all p ≤ 0.001); multivariate analyses showed that having a PTSD positive father (OR 3.0, 95% CI 2.05–4.50) or mother (OR 4.4, 95% CI 2.99–6.45) significantly increased risk of child PTSD | Post-flood PTSD: children 4.7%, parents 11.2% |

| Peng-2011 [37] | Cross-sectional | 7038 children aged 7–15 | Multistage cluster random sampling | Flood (Dongting Lake) | PTSD | DSM-IV criteria (interview) | ~18 months | Flood type (flash > collapsed > soaked) and whether school reopening was delayed (yes > no) were significantly associated with PTSD (p < 0.001) | Post-flood PTSD: 2.05% |

| Quan-2017 [44] | Cross-sectional | 951 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Rainstorms | PTSD | PCL-5 (self-reported survey) | 1 week | Presence of PTSD was significantly correlated with rainstorm-related experiences and perceived severity of disaster (p = 0.01) | Post-rainstorm PTSD: 15.2% identified as probable cases |

| Wu-2011 [42] | Cross-sectional | 968 students who walked home during storm | Convenience sampling | Snowstorm | PTSD | IES-R (self-reported survey) | 3 months | Walk time (5+ hours > 2–5 h > 0–2 h) and walk distance (20+ km > 10–20 km > 0–10 km) were significantly associated with PTSD (p < 0.01); binary analyses showed walk distance (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01) significantly increased odds of PTSD | Post-snowstorm PTSD: 14.5% |

| Xu-2018a [49] | Cross-sectional | 247 middle school students (grades 7–9) | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD, depression | CPSS, CES-DC (self-reported surveys) | 3 months | Significantly greater odds of PTSD among children who had injured relatives/friends (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.01–3.92), feared injury/death (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.14–3.24); significantly greater odds of depression among children who had injured relatives/friends (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.03–4.07) | Post-tornado PTSD: 57.5%, depression: 58.7% |

| Xu-2018b (sample related to Xu-2018a) [50] | Cross-sectional | 431 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | Depression | CES-DC (self-reported survey) | 9 months | ||

| Xu-2018c (same sample as Xu-2018a) [51] | Cross-sectional | 247 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD, depression | CPSS, CES-DC (self-reported surveys) | 6 months | ||

| Yuan-2018a (sample related to Xu-2018a) [52] | Cross-sectional | 431 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD | CPSS (self-reported survey) | 9 months | ||

| Yuan-2018b (same sample as Xu-2018a) [53] | Cross-sectional | 247 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD | CPSS (self-reported survey) | 3 months | ||

| Zhang-2018 (sample related to Xu-2018a) [54] | Cross-sectional | 443 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Tornado | PTSD | CPSS (self-reported survey) | 12 months | ||

| Zhen-2016 (same sample as Quan-2017) [55] | Cross-sectional | 951 middle school students | Multistage cluster random sampling | Rainstorms | PTSD | PCL-5 (self-reported survey) | 2 months | PTSD was significantly correlated with severity of rainstorm-related experiences (p < 0.001) | |

| India (n = 3) | |||||||||

| Chowhan-2016 [40] | Cross-sectional | 100 children aged 6–17 from local school | Systematic sampling | Snowstorm, avalanche | DSM-IV disorders | MINI-KID (interview) | 5 years | Observed 54 post-event diagnoses among 41 patients: PTSD (14), GAD (5), separation anxiety disorder (4), MDD (4), dysthymia (3), agoraphobia (3), social phobia (3), adjustment disorder (3), suicidality (2), PD (2), mania (1), specific phobia (1), substance abuse (1) | |

| Hassan-2018 (mixed methods) [43] | Cross-sectional | 64 children who had resumed schooling | Convenience sampling | Flood | PTSD | Quantitative: CRIES-8; Qualitative: group discussions (interviews) | 1 month | Main qualitative themes: initial reactions to shock, intrusion, flashbacks, avoidance, difficulty in concentration, and helplessness and sadness | |

| Kar-2007 [41] | Cross-sectional | 447 students | Multistage stratified cluster random sampling | Cyclone | PTSD, MDD | Psychiatrist evaluation using ICD-10-DCR criteria (interview) | 12 months | Exposure level was significantly associated with PTSD (high vs. low OR 4.10, 95% CI 2.30–7.30) | Post-cyclone PTSD: 30.6% (an additional 13.6% considered subsyndromal); MDD: 23.7% (comorbid with PTSD in 34.3% of this group) |

| Pakistan (n = 2) | |||||||||

| Ahmad-2011 [38] | Cross-sectional | 522 students aged 10–16 | Random sampling | Flood | PTSD | IES-R (self-reported survey) | 4 months | PTSD score significantly higher among those who were displaced vs. those who were not displaced (p = 0.000) | Post-flood PTSD: 3.06% none, 14.17% partial, 8.81% probable, 73.94% high |

| Sitwat-2015 [36] | Cross-sectional | 205 females aged 13–19 | Purposive sampling | Flood | PTSD, GAD, MDD | Diagnostic interview using DSM-IV-TR (interview) | ~12 months | Post-flood PTSD: 2%, GAD: 1%, MDD: 2% | |

| Philippines (n = 2) | |||||||||

| Mordeno-2018 [56] | Cross-sectional | 225 child and adolescent survivors at evacuation centers | Convenience sampling | Typhoon (Washi) | ASD, depression | ASDI (interview), DSRS-C (self-reported survey) | 1 month | ||

| Nalipay-2018 [57] | Cross-sectional | 446 college students | Convenience sampling | Typhoon (Haiyan) | PTSD | PCL-5 (self-reported survey) | 3 months | Post-typhoon PTSD: 16.14% | |

| Namibia (n = 1) | |||||||||

| Taukeni-2016 [58] | Cross-sectional | 429 students aged 8–18 | Stratified sampling | Flood | PTSD | CTSQ (self-reported survey) | 2 years | Post-flood PTSD: 72.8% of children 13+, 55.2% of children <13 | |

| Dominica (n = 1) | |||||||||

| Tavernier-2019 [45] | Cross-sectional | 174 college students | Not specified (sample from a larger study) | Tropical storm (Erika) | PTSD | Adapted PTSD Checklist (self-reported survey) | 6 months | PTSD was significantly correlated with severity of tropical storm exposure (p < 0.05) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharpe, I.; Davison, C.M. A Scoping Review of Climate Change, Climate-Related Disasters, and Mental Disorders among Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052896

Sharpe I, Davison CM. A Scoping Review of Climate Change, Climate-Related Disasters, and Mental Disorders among Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052896

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharpe, Isobel, and Colleen M. Davison. 2022. "A Scoping Review of Climate Change, Climate-Related Disasters, and Mental Disorders among Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052896

APA StyleSharpe, I., & Davison, C. M. (2022). A Scoping Review of Climate Change, Climate-Related Disasters, and Mental Disorders among Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052896