Active Ageing in Italy: An Evidence-Based Model to Provide Recommendations for Policy Making and Policy Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

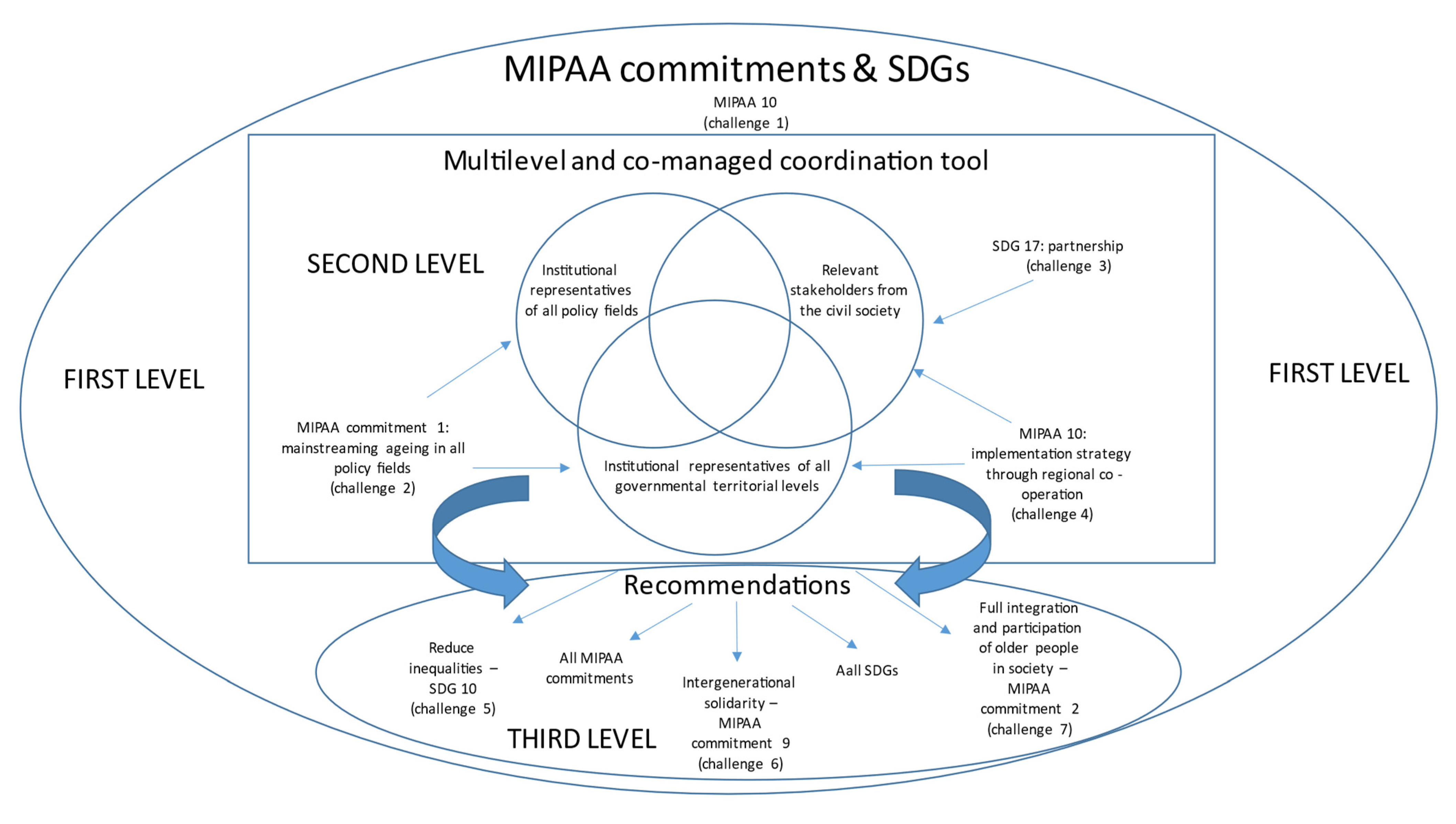

2. Policy Making in the Field of Active Ageing: Main Challenges and Conceptual Framework

- C1.

- In order to deal with policy making in this field and being sure not to neglect the many interconnected aspects, national applications of the AA concept should be in line with a proper and strong AA comprehensive international framework to ensure its homogeneity and success at the wider international level. Policy makers should concentrate their attention and efforts on the heterogeneity and diversity of experiences of later life, relying on conceptual frameworks in which this diversity is modelled, as the outcome of a lifetime’s interaction between a set of intrinsic capacities of individuals and the social environment in which they live [18]. In this perspective, AA frameworks should advocate a holistic approach, arguing that multiple aspects of older adults’ activities, specifically participation, health, security, psychological well-being, lifestyle and financial resources intertwine to determine the quality of the ageing experience, and that each of these aspects are essential in achieving and maintaining well-being in later life [21].

- C2.

- With the aim to avoid sectorial approaches of policy making in the area of AA, usually confined to social services and health departments, the concept of mainstreaming ageing across all policy domains should be applied through a systematic integration of AA issues across all relevant policy fields [17]. Mainstreaming ageing has become a priority on policy agendas throughout Europe, but it is still not fully understood and implemented [22]. Thus, undeniable national achievements in various ageing-specific sectors co-exist with significantly less progress in mainstreaming ageing into wider policy discourse and development strategies. For instance, there is still a substantial gap between the comprehensive philosophy of the UN Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (MIPAA) and the related commitments for its implementation [23] and the sectoral translation of the MIPAA commitments into national programs [24]. A real involvement of public authorities at various levels is needed. Different stakeholders across different policy areas are compelled to work together on designing effective and comprehensive strategies for active ageing [25]. When social policy goals aimed at older persons are incorporated into overall national development plans, this integration may have a positive long-term effect on the well-being of the older population [24].

- C3.

- It has also been observed, as a criticism, that AA is politically pursued mainly through a top-down approach. See for example: https://statswiki.unece.org/display/AAI (accessed on 10 January 2022), while AA should not be a top-down imposition, but rather opportunities should be provided for citizens to take action from the bottom-up, through consultative and/or co-decisional participative tools. This is highly important in the perspective of producing socially innovative solutions in order to solve social problems [26,27]. The effectiveness of the stakeholder involvement depends on its capacity to address local inputs through a coordinated and multilevel approach among public institutions and actors from civil society and the Third Sector [28]. According to this, horizontal networks of public, private, and non-profit organizations provide new structures of governance, as opposed to hierarchical organizational decision making [29]. In fact, stakeholder and user involvement is often limited to the collection of citizen’s opinions about a specific issue, and frequently results in low-profile deliberations, while co-decisional approaches set the conditions for a deliberative dialogue between governors and governed [20]. This would allow to better consider motivations, preferences and constraints of older people by also ensuring sustainability of policy making in this field. The latter is often and seriously jeopardized when participative tools are implemented without providing or enforcing coordination and informative systems among national, regional and local levels, resulting in a lack of continuous involvement of the non-governmental organizations of seniors in the consultation process [30].

- C4.

- The widespread exercise of comparing different contexts in terms of AA has been largely criticized [31], while scientists have underlined the strong need of respecting national and cultural diversity in implementing AA policies [16], since older people’s values and aims related to AA dimensions may vary considerably depending on the studied context, culture, and traditions [32], which can refer either to differences between countries or within the country. Therefore, the concept should be applied by respecting cultural diversity concerning activity patterns and norms. This is intended not only across countries, but also at the sub-national level (e.g., across country-regions) [33,34]. In fact, within countries, there are also large variations between ethnic/social groups in their preferences for different forms of activity [16]. In this regard, policy making on AA should pay attention to the local situation, and expect differences also in health, participation and security [35]. Respecting national and cultural diversity is of paramount importance to achieve the full potential of AA, without condoning practices that transgress national and international equality and human rights objectives and laws [36].

- C5.

- Another issue concerns the limited efforts to activate older people who face more barriers in accessing AA, is those with less resources. AA initiatives should consider inequalities by providing opportunities for all people, including those with less available resources [32]. To achieve this goal, it is important to explicitly address gender, social class and other inequalities among older cohorts [37]. The lack of personal (i.e., social, human, cultural) resources represents a barrier to AA: as people grow older, disparities in terms of both wealth and other socio-economic resources are accentuated, with inequalities grounded in gender, class, ethnicity, sexual orientation, health and other aspects [38]. Actions that dismantle discrimination, and level up socio-economic conditions, will likely uplift the trajectory of healthy and active ageing for all people. In particular, in order to reduce accumulated inequalities, the following areas should be addressed by policy interventions: structures, norms and processes that shape and differentially affect a person’s likelihood to age well across the life course; integration across health and social care systems to mitigate vulnerabilities, and strengthen social capacities and abilities; measuring and assessing the impact of actions to better describe and identify inequities, and evaluate what initiatives work in different contexts [39,40].

- C6.

- A further challenge is moving from an age-segregation to an age-integration perspective, through policy making in this field. This means taking into account the life-course perspective, through intergenerational exchange [41], promoting an intergenerational approach as a promising measure to support development and use of potentials of generativity in older people, in the interest of the old, the young, and the whole society [19]. The application of the concept should not generate competition between generations, but rather, since ageing is a process which people experience independently by their age, the concept should be applied in a life-course perspective. An intergenerational approach to AA does not consist of linking it only to intergenerational solidarity, but also to intergenerational relationships [42]. In fact, intergenerational solidarity often recalls the idea of mutual assistance, while intergenerational relationships are more referred to the structural interdependence of all individuals, as part of the society. According to this, the maintenance of an intergenerational perspective is considered as an important feature of a modern approach to AA in order to develop “fairness between generations as well as the opportunity to develop activities that span the generations” [43] (p. 125). It is through the encounters between ageing as a life-course process and generations as social relationships that intergenerational ageing becomes effective [42].

- C7.

- One of the main criticisms is that policy making in this field addresses mainly employment-related issues, neglecting other areas of social activation. Thus, there is the need to avoid a purely economic/productive interpretation of AA in terms of only improving the labour market participation of older people. Indeed, it is also important promoting other meaningful activities (besides paid work) that can contribute to the well-being of older individuals and societies at large (e.g., volunteering). Although a comprehensive approach on AA was originally developed by the WHO and the United Nation (UN), a productivist approach focused on employment seems to be still dominant [16]. The productivist model tends to promote rational policy behaviour based on “objective and precise value-neutral calculations of the cost-benefits of policy changes” [44] (p. 236), which has the potential to reduce older persons to homos economicus and to means for utilitarian ends [45]. Such utilitarian treatment of the productive dimension of AA tends to render productive accomplishment equivalent to personal worth [46], obstructing other pathways for personal development than the work-based pathway [47]. In this regard, as noted by the WHO, a holistic approach to AA should pursue continued “participation in social, economic, cultural, spiritual and civic affairs, not just the ability to be physically active or participate in the workforce” [3] (p. 12).

3. Active Ageing from Theory to Practice: Examples of National Active Ageing Strategies

3.1. Describing the Strategies

3.2. Analysing the Strategies

4. Aim of the Study

5. The Ageing Situation in Italy

6. Operationalization of the Model in Italy

6.1. Building the Coordination Tool

6.2. Working on the Framework

6.3. Studying the State of the Art of Public Policies in the Field of Active Ageing

6.4. Towards an Improvement of the State of the Art: Realising Recommendations for Policy Making

- The project team analysed the state of art of AA policies [74,76], drown up through a participated approach with the stakeholder network of the PoA, and based on one national report and 35 individuals (i.e., organization-based reports concerning each of the Ministries, Departments of the Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers, Regions and Autonomous Provinces, i.e., public administrations—involved in the project).

- Organizations represented in the stakeholder network provided, individually, written feedback, at different levels of the process (on draft documents of the recommendations) and, in particular, a first input was delivered by the network in November-December 2020 through a web-consultation in the form of a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire is available for consultation here: https://forms.gle/rxFidDkQXnSsejab9 (accessed on 12 October 2021). The questionnaire was made of open questions designed to integrate the national report of the state of art with potential undervalued aspects.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Recommendations for the Adoption of Active Ageing Policies in Italy

| Recommendation n.1 |

| To provide long-term tools for coordination, analysis, planning and monitoring of active ageing policies at national level, by involving all the Ministries, Departments at the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, Regions and Autonomous Provinces. |

| Recommendation n.2 |

| To provide long-term tools for coordination, analysis, planning, implementation and monitoring of active ageing policies at regional level, by involving all regional departments/services, as well as other important institutional regional actors. |

| Short-Term Objectives: |

|

| Recommendation n.3 |

| To ensure full integration and participation of older people in society at the national and regional levels through specific and adequate laws and regulations |

| Recommendation n.4 |

| To ensure actual (rather than just remaining on paper) full integration and participation of older people in society as provided by laws, decrees, resolutions and other regulatory documents. |

| Short-Term Objectives: |

|

| Recommendation n.5 |

| To ensure that, beyond representatives of institutional/governmental bodies, both at the national and the regional level, also all relevant stakeholders (from the third sector and civil society, the academic-scientific sector, etc.) are included in long-term tools for the analysis, planning, implementation and monitoring of policies in the field of active ageing, in order to guarantee co-decisional participatory mechanisms. |

| Short-Term Objectives: |

|

| Recommendation n.6 |

| To promote policies to combat inequalities and poverty, in order to guarantee the possibility of ageing actively also to older people with few resources available in terms of health and socio-economic conditions. Opportunities should be provided not only in terms of economic help, but also in terms of activation in the various domains of active ageing, according to the characteristics of the territory and promoting the development of digital skills among older people. |

| Short-Term Objectives: |

|

| Recommendation n.7 |

| In order to promote adequate social protection in response to demographic changes, and their socio-economic consequences, it is necessary build a new welfare system through the development of a multi-level institutional governance, both at national and regional level, which integrates the perspective of ageing throughout life, and in the different life spheres. |

| Short-Term Objective: |

|

| Recommendation n.8 |

| To promote, at all levels and alongside possible existing ones, the implementation of policies stimulating age management initiatives both in the private and the public sectors. These initiatives are necessary to guarantee: |

|

| Recommendation n.9 |

| To promote active labor market policies at national and local level, which should be functional to vocational retraining, to skill-updating and to work reintegration of all those who wish so (mature unemployed and/or disadvantaged individuals; retired older people, etc.). |

| Recommendation n.10 |

| To strengthen lifelong learning within a global strategy with the “Plan for the development of skills of the adult population” as a strategic tool, to represent a solid reference base for guiding targeted interventions that could be also funded within the European programming. |

| Recommendation n.11 |

| To strengthen lifelong learning by promoting intergenerational knowledge exchange in a bidirectional way across various domains (e.g., areas, for example, passing on of knowledge by older people; passing on of digital skills by younger people). |

| Recommendation n.12 |

| In order to improve the implementation of preventative tools, to provide training programs and policies able to strengthen competences in the community, and also including the promotion of active ageing among other tools. |

| Recommendation n.13 |

| To create bridges between the health (doctors, geriatricians, health workers in general) and the gerontological (gerontologists, professions relating to the social aspects of ageing) perspectives, also through a two-way training for the operators of these two fields, in order to exploit and coordinate in a more effective way the activities developed in the area of active ageing. |

| Recommendation n.14 |

| To consider the issue of gender inequalities, in all areas of active ageing. |

| Recommendation n.15 |

| To plan tools to implement gender-related initiatives required by regulations. |

| Recommendation n.16 |

| To promote specific policies and initiatives to combat violence, abuse and discrimination against older women, also in light of the social transformations of the family under way, thus fostering their activation in the various active ageing domains. |

| Recommendation n.17 |

| To facilitate caregivers in the access to all relevant information they need (including information on how to carry out care activities in relation to the specific diseases suffered by older people), through the creation of specific digital platforms (or the development of those already existing), for also providing training and information on the management of the disease. |

| Recommendation n.18 |

| To promote the recognition of the rights and of the activities carried out by the caregiver, in the perspective of combating inequalities, including those related to health; promoting a gender approach, also creating a network in the community in order to facilitate the relationships between families and public and private services, also considering elements of training for family carers. |

| Recommendation n.19 |

| Through services and devices, to provide older people and their caregivers the possibility of combining the illness and the care activity with their life-project within the community, e.g., relative to the work for the labour market or to other active ageing domains (learning, leisure and cultural activities, volunteering, etc.). |

| Recommendation n.20 |

| It is necessary to encourage intergenerational dialogue in a positive and bidirectional way, also to the aim of promoting the life-course perspective. |

| Short-Term Objective: |

|

| Recommendation n.21 |

| To promote initiatives to facilitate mobility and access to community services (including educational ones) of older people, both in terms of time-flexibility and of adaptation of public transportation, as well as of pedestrian and cycle walkways. |

| Recommendation n.22 |

| To promote both the development of enabling technologies and the adaptation of building and urban planning standards, for the reorganization of living spaces, even in co-housing situations, in an active ageing perspective. To also adopt criteria for the assessment of the quality of the houses of older and frail people. |

| Recommendation n.23 |

| To promote the different types of co-housing (e.g., inter and intra-generational, neighborhood co-housing, eco-rural villages, social housing, etc.) in older age and innovative strategies of urban regeneration, in order to promote active participation in social life. |

| Recommendation n.24 |

| To provide plans taking into account both older people’s needs and the contribution that they can offer in all the stages: preparation, support and response to the emergency. |

| Recommendation n.25 |

| To promote data collection and data process related to health and living conditions of older people during emergency situations, to encourage the implementation and the transferability of good practices. |

| Recommendation n.26 |

| To consider the condition of older people in emergency situations, in a cross-cutting way with respect to the MIPAA commitments and the Sustainable Development Goals previously discussed. |

| Recommendation n.27 |

| To keep active ageing at the top of the political agenda at the national, regional and local governmental level, also via media, through an effort by all the relevant stakeholders. |

| Recommendation n.28 |

| To take into account, in all the relevant laws and policies at all levels, within public, private and third sector organisations, including by older people themselves, each according to the respective competences and available resources, all the recommendations expressed in this document, to guarantee that the rights of older people are respected. |

| Short-Term Objective: |

|

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Meier, V.; Werding, M. Ageing and the welfare state: Securing sustainability. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2010, 26, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework 2002; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; p. 12. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67215 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Peel, N.; Bartlett, H.; Mclure, R. Healthy ageing: How is it defined and measured? Australas. J. Ageing 2004, 23, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, A.; Naegele, G.; Reichert, M. Volunteering by Older People in the EU; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Ireland; Luxembourg, 2011; pp. 1–64. ISBN 978-92-897-1012-1. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A.; Maltby, T. Active ageing: A strategic policy solution to demographic ageing in the European Union. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2012, 21, S117–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow-Howell, N. Volunteering in later life: Research frontiers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. 2010, 65, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A. The Future of Ageing Research in Europe: A Road Map; University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, D. Oldest old are not just passive recipients of care. BMJ 2007, 334, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Marsillas, S.; De Donder, L.; Kardol, T.; van Regenmortel, S.; Dury, S.; Brosens, D.; Smetcoren, A.S.; Braña, T.; Varela, J. Does active ageing contribute to life satisfaction for older people? Testing a new model of active ageing. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Results and Overall Assessment of the 2012 European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0562&from=EN (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- European Commission. Green Paper on Ageing. In Fostering Solidarity and Responsibility between Generations; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/1_en_act_part1_v8_0.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Walker, A.; Foster, L. Active Ageing: Rhetoric, Theory and Practice. In The Making of Ageing Policy; Ervik, R., Lindén, T., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, L.; Walker, A. Active and Successful Aging: A European Policy Perspective. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Guidelines for Mainstreaming Ageing; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/ECE-WG.1-37_Guidelines_for-Mainstreaming_Ageing_1.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Zaidi, A.; Howse, K. The Policy Discourse of Active Ageing: Some Reflections. J. Popul. Ageing 2017, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E.; Hinner, J.; Kruse, A. Potentials of Survivors, Intergenerational Dialogue, Active Ageing and Social Change. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Falanga, R.; Cebulla, A.; Principi, A.; Socci, M. The Participation of Senior Citizens in Policy-Making: Patterning Initiatives in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, L.; Miller, E. Active Ageing: Developing a Quantitative Multidimensional Measure. In Active Ageing, Active Learning: Issues and Challenges; Tam, M., Boulton-Lewis, G., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, B.; Zaidi, A. Trends and Priorities of Ageing Policies in the UN-European Region. In Mainstreaming Ageing; Marin, B., Zaidi, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. The Regional Implementation Strategy for MIPAA for the UNECE Region; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/pau/RIS.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Zelenev, S. Towards a “society for all ages”: Meeting the challenge or missing the boat. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2008, 58, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andor, L. Promoting employment and participation in society of older people—A challenge for the next 50 years. In Proceedings of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Ministerial Conference on Ageing, Vienna, Austria, 20 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring, A.; Smith, S.; Dobner, S. Social Innovation for Active and Healty Ageing. A Case Study Collection. King Baudouin Found. 2014, 24, 1–172. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/file/911/download_en%3Ftoken=AU3NRuLP (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Socci, M.; Clarke, D.; Principi, A. Active aging: Social entrepreneuring in local communities of five European countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Building Competitive Regions—Strategies and Governance; OECD: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, L.B.; Nabatchi, T.; O’Leary, R. The New Governance: Practices and Processes for Stakeholder and Citizen Participation in the Work of Government. Public Adm. Rev. 2005, 65, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinfelde, A.; Paula, L. Seinior Communities within a Context of Successful Ageing Policy in Latvia. In Proceedings of the International Conference “Economic Science For Rural Development” No 40, Jelgava, Latvia, 23–24 April 2015; pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lamura, G.; Principi, A.; Di Rosa., M. 2018 Active Ageing Index Analytical Report; UNECE/European Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen, V. Beyond Successful and Active Ageing. In A Theory Model of Ageing; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2016; pp. 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- Zannella, M.; Principi, A.; Lucantoni, D.; Barbabella, F.; Di Rosa, M.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Socci, M. Active ageing: The need to address sub-national diversity. An evidence-based approach for Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Domínguez-Rodríguez, A.; Varlamova, M.; Barbabella, F.; Lamura, G.; Socci, M. The Active Ageing Index and policy-making in Italy. Ageing Soc. 2021, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, E.N.; Braun, K.L.; Hogervorst, E. Three pillars of active ageing in Indonesia. Asian Popul. Stud. 2012, 8, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Perceptions of active ageing in Britain: Divergences between minority ethnic and whole population samples. Age Ageing 2009, 38, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinca, S.; Rodrigues, R.; Schmidt, A.; Zolyomi, E. Gender and Social Class Inequalities in Active Ageing: Policy Meets Theory; European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research: Viena, Austria, 2016; Available online: https://www.euro.centre.org/downloads/detail/1558 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Scharf, T.; Keating, N. From Exclusion to Inclusion in Old Age; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sadana, R.; Blas, E.; Budhwani, S.; Koller, T.; Paraje, G. Healthy Ageing: Raising Awareness of Inequalities, Determinants, and What Could Be Done to Improve Health Equity. Gerontologist 2016, 56, S178–S193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östlin, P.; Schrecker, T.; Sadana, R.; Bonnefoy, J.; Gilson, L.; Hertzman, C.; Kelly, M.P.; Kjellstrom, T.; Labonté, R.; Lundberg, O.; et al. Priorities for Research on Equity and Health: Towards an Equity-Focused Health Research Agenda. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannefer, D.; Feldman, K. Age Integration, Age Segregation, and Generation X: Life-Course Perspectives. Generations. J. Am. Soc. Aging 2017, 41, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, M. Active Ageing and Intergenerational Solidarity in Europe: A Conceptual Reappraisal from a Critical Perspective. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2012, 10, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. A strategy for active ageing. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2002, 55, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, C.L. Theoretical Perspectives on Old Age Policy: A Critique and a Proposal. In The Need for Theory: Critical Approaches to Social Gerontology; Biggs, S., Lowenstein, A., Hendricks, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; He, L.; Chen, H. Balancing instrumental rationality with value rationality: Towards avoiding the pitfalls of the productivist ageing policy in the EU and the UK. Eur. J. Ageing 2019, 17, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergen, M.M.; Gergen, K.J. Positive Aging: Reconstructing the Life Course. In Handbook of Girls’ and Women’s Psychological Health: Gender and Well-Being Across the Lifespan; Worell, J., Goodheart, C.D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 416–426. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, S. Toward critical narrativity: Stories of aging in contemporary social policy. J. Aging Stud. 2001, 15, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, A. Working Group on Ageing Population and Sustainability (WGA). Presentation at the 103rd Meeting of the UNECE Executive Committee, Palais des Nations, Geneva, 1 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Naydenova, Z. National Strategy for Active Ageing in Bulgaria (2019–2030). Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/pau/age/WG.12/Presentations/2_National-Strategy-Active-Ageing-Bulgaria.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs of the Czech Republic. National Action Plan Promoting Positive Ageing for 2013–2017. Government of the Czech Republic, 2014. Available online: https://www.mpsv.cz/documents/20142/953091/NAP_EN_web.pdf/75098fbf-2912-91e1-7547-c41ad26bfbe1 (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Department of Health. National Positive Ageing Strategy 2013–2017 in Ireland; Department of Health: Dublin, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. The Active Ageing Challenge: For Longer Working Lives in Latvia; World Bank Group. The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for Active Ageing. National Strategic Policy for Active Ageing. Malta 2014–2020; Parliamentary Secretariat for Rights of Persons with Disability and Active Ageing: Birkirkara, Malta, 2014. Available online: https://family.gov.mt/en/Documents/Active%20Ageing%20Policy%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- IMAD. Active Ageing Strategy; Government of the Republic of Slovenia. IMAD: Ljubljana, Sloveny, 2018. Available online: https://www.umar.gov.si/fileadmin/user_upload/publikacije/kratke_analize/Strategija_dolgozive_druzbe/UMAR_SDD_ang.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- IMSERSO. Framework of Action for Older Persons; IMSERSO: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, A.; Harper, S.; Howse, K.; Lamura, G.; Perek-Białas, J. Building Evidence for Active Ageing Policies. Active Ageing Index and its Potential; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sidorenko, A. Active ageing in the time of COVID-19 with references to European and post-Soviet countries. Int. J. Ageing Dev. Ctries 2021, 6, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Macia, M.; Segura, M.; Conejero, E. Challenges of the Aging Policies in Spain. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interreg Europe. Good Practice: Active Ageing Strategy. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/policylearning/good-practices/item/3335/active-ageing-strategy/ (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Sowa-Kofta, A. Establishing Healthy and Active Ageing Policies in Poland, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria. Polityka Społeczna 2020, 7, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A. Creating and using the evidence base: The case of the ActiveAgeing Index. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formosa, M. Activity theory as a foundation for active ageing policy: The Maltese experience. EXLIBRIS Bibl. Gerontol. Społecznej 2020, 1, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeski, S.; Sylvan, D. How foreign policy recommendations are put together: A computational model with empirical applications. Int. Interact. 1999, 25, 301–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE; European Commission. Active Ageing Index 2014: Analytical Report; UNECE; European Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/file/949/download_en%3Ftoken=2gUgJDuZ (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- São José, J.M.; Timonen, V.; Amado, C.A.F.; Santos, S.P. A critique of the Active Ageing Index. J. Aging Stud. 2017, 40, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principi, A.; Tibaldi, M.; Quattrociocchi, L.; Checcucci, P. Criteria-Specific Analysis of the Active Ageing Index (AAI) in Italy; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kudins, J. Determinants of the elderly employment in Latvia. Econ. Sci. Rural. Dev. Conf. Proc. 2021, 55, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabari, M.; Amisi, M.M.; David-Gnahoui, E.; Bedu-Addo, D.; Goldman, I. Evidence-informed policy and practice: The role and potential of civil society. Afr. Eval. J. 2020, 8, a470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspalter, C.; Walker, A. Introduction. In Active ageing in Asia; Walker, A., Aspalter, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Ageing 1950–2050; United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Il futuro demografico del Paese. In Previsioni Regionali Della Popolazione Residente al 2065; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2011. Available online: http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/48875 (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Principi, A.; Lamura, G.; Jensen, P.H. Conclusions: Enhancing volunteering by older people in Europe. In Active Ageing: Voluntary Work by Older People in Europe; Principi, A., Jensen, P.H., Lamura, G., Eds.; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2000; pp. 315–342. [Google Scholar]

- INAPP. Report for Italy for the Implementation of the MIPAA/RIS Strategy 2018/2022; INAPP: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Cela, E.; Socci, M.; Lucantoni, D.; Zannella, M.; Principi, A. Active ageing in Italy: A systematic review of national and regional policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jann, W.; Wegrich, K. Theories of the Policy Cycle. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics and Methods; Fischer, F., Miller, G.J., Sidney, M.S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Cela, E.; Di Matteo, C.; Socci, M.; Lamura, G.; Checcucci, P.; Principi, A. New Multilevel Partnerships and Policy Perspectives on Active Ageing in Italy: A National Plan of Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breza, M.; Perek-Białas, J. The Active Ageing Index and Its Extension to the Regional Level; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2014; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=12940&langId=en (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Marsillas Rascado, S. Active Ageing Index at Subnational Level in Spain; UNECE/European Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Villar, F. Successful ageing and development: The contribution of generativity in older age. Ageing Soc. 2012, 32, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, G.; Nuvolari, A.; Vasta, M. The origins of the Italian regional divide: Evidence from real wages, 1861–1913. J. Econ. Hist. 2018, 79, 63–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, J. Design and management of participatory public policy making. Public Manag. Int. J. Res. Theory 1999, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, I.; Van Daalen, E.; Bots, P. Perspectives on Policy Analysis: A Framework for Understanding and Design. Int. J. Technol. Policy Manag. 2004, 4, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 22 December 2003: A/RES/58/134; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Available online: https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/A/RES/58/134 (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- World Health Organization. The Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health 2016–2020: Towards a World in Which Everyone Can Live a Long and Healthy Life; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_R3-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Barbabella, F.; Principi, A. (Eds.) Le Politiche Per L’invecchiamento Attivo in Italia. Lo Stato Dell’arte Nelle Regioni, Nelle Province Autonome, Nei Ministeri e Nei Dipartimenti Presso la Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri: Raccolta Dei Rapporti. Dipartimento Per le Politiche Della Famiglia-IRCCS INRCA 2020. Available online: http://famiglia.governo.it/media/2267/le-politiche-per-l-invecchiamento-attivo-in-italia-raccolta-dei-rapporti.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Barbabella, F.; Checcucci, P.; Aversa, M.L.; Scarpetti, G.; Fefè, R.; Socci, M.; Di Matteo, C.; Cela, E.; Damiano, G.; Villa, M.; et al. Active Ageing Policies in Italy Report on the State of the Art. 2022. Available online: https://famiglia.governo.it/media/2641/active-ageing-policies-in-italy.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Centre for Ageing Research and Development in Ireland. 10 Guidelines for Writing Policy Recommendations 2012; Centre for Ageing Research and Development in Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2012; Available online: https://www.lenus.ie/bitstream/handle/10147/221377/Factsheet.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Davies, H.T.; Nutley, S.M. What Works? Evidence-Based Policy and Practice in Public Services; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lucantoni, D.; Checcucci, P.; Socci, M.; Fefè, R.; Lamura, G.; Barbabella, F.; Principi, A.; Raccomandazioni Per L’adozione di Politiche in Materia di Invecchiamento Attivo. Dipartimento per le Politiche Della Famiglia-IRCCS INRCA 2021. Available online: https://famiglia.governo.it/media/2329/raccomandazioni-per-ladozione-di-politiche-in-materia-di-invecchiamento-attivo.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- UNECE. Policy Brief: Older Persons in Emergency Situations; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ECE_WG1_36_PB25.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Barbosa, C.; Feio, P.; Fernandes, A.; Thorslund, M. Governance strategies to an ageing society: Local role in multilevel processes. J. Comp. Politics 2016, 9, 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy. In A Place-based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, T.; Biggs, S. International and European policy on work and retirement: Reinventing critical perspectives on active ageing and mature subjectivity. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, A. Intergenerational relations across the life course. Adv. Life Course Res. 2012, 17, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, D. A life course approach to healthy aging, frailty, and capability. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, S.; Jones, R.N.; Glymour, N.M. Implications of lifecourse epidemiology for research on determinants of adult disease. Public Health Rev. 2010, 32, 489–511. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Scenari Sugli Effetti Demografici di Covid-19 per L’anno 2020; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/04/Scenari-sugli-effetti-demografici-di-Covid-19_Blangiardo.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

| Challenge | Possible Solution | |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Narrow policy approach | To adopt a comprehensive international policy framework |

| C2 | Policy silos | To mainstream active ageing in all policy fields |

| C3 | Top-down approach | To involve relevant stakeholders through co-decisional tools |

| C4 | One-fits-all approach | To respect cultural diversity by differentiating policy solutions according to the contexts |

| C5 | Limited equal opportunities for older people | To provide opportunities for all, considering inequalities |

| C6 | Age-segregation approach | To adopt a life-course perspective through promoting intergenerational relationships and solidarity |

| C7 | Mainly work-oriented approach | To promote participation in all social domains |

| MIPAA Commitment | SDGs Linked to the MIPAA |

|---|---|

| 1 Mainstreaming ageing | 1 No poverty |

| 2 Integration and participation | 3 Good health and well-being |

| 3 Economic growth | 4 Quality education |

| 4 Social security | 5 Gender equality |

| 5 Labour markets | 8 Decent work and economic growth |

| 6 Lifelong learning | 10 Reduced inequalities |

| 7 Quality of life, independent living and health | 11 Sustainable cities and communities |

| 8 Gender equality | 16 Peace, justice and strong institutions |

| 9 Support to families providing care and intergenerational solidarity | 17 Partnerships for the goals |

| 10 Regional co-operation |

| Country | Title | Year/s | Recommendations 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | National Strategy for Active Ageing in Bulgaria [49] | 2019–2030 | No |

| Czech Republic | National Action Plan Supporting Positive Ageing [50] | 2013–2017 | No |

| Ireland | The National Positive Ageing Strategy [51] | 2013 | No |

| Latvia | Developing a Comprehensive Active Ageing Strategy for Longer and Better Working Lives [52] | 2014–2016 | Yes |

| Malta | National Strategic Policy for Active Ageing [53] | 2014–2020 | Yes |

| Slovenia | Active Ageing Strategy [54] | 2017 | Yes * |

| Spain | Framework of action for older persons [55] | 2014 | Yes ** |

| Country | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Czech Republic |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Ireland |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Latvia |  |  |  | N.A. |  |  |  |

| Malta |  |  |  | N.A. |  |  |  |

| Slovenia |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Spain |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

: Covered

: Covered  : Partially covered

: Partially covered  : Uncovered.

: Uncovered.| Subject | MIPAA | SDG | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mainstreaming ageing in all policy fields | 1 | Overcoming the sectoral visions and fostering a system perspective in order to address the challenges related to ageing. In the field of active ageing, positive experiences both at the national and local levels, are those that promote and put into practice an inter-ministerial or inter-departmental (at the regional level) collaboration, overcoming the classic approach that delegates the production and management of interventions in this area to social and health policies. | |

| 2 To ensure the full integration and participation of older people in society | 2 | To promote the integration and participation of older people in society, in all areas of active ageing, without exception, to ensure that all possible opportunities are provided, among which older people can freely choose on the basis of their preferences, motivations and predispositions. | |

| 3 To strengthen the partnership | 17 | To involve relevant stakeholders in all processes (from the production of policies on active ageing, to the implementation of services and related monitoring) with consultation and co-decisional tools. The subject is strongly linked to the previous two, as it strengthens the integration and participation of older people in society by integrating consultation and co-decision into mainstream ageing tools. | |

| 4 To promote the fight against inequalities and poverty, fostering a fair and sustainable economic growth | 3 | 1;10 | Inequalities are considered as barriers that prevent access to active ageing paths, which must be guaranteed to the entire older population regardless of differences in cultural resources, income, education and health, precisely in order to reduce them. This vision, therefore, does not include the strictly welfare part of older people in need of social and health care, but rather those cases in which inequalities are given by differences in access to resources and the ability to achieve their own life goals, with respect, for example, to specific socio-economic conditions. |

| 5 Modification of social protection systems in response to demographic changes and their socio-economic consequences | 4 | While generally this commitment is exclusively traced back to the issue of pensions, in reference to active ageing, by social protection it is meant something broader, which, in addition to the theme of combating inequalities and poverty (see the previous point), it includes the construction and redefinition of a new welfare system. | |

| 6 Adapting the labor market to respond to the economic and social consequences of an ageing population | 5 | 8 | Employment is considered as an important dimension, among those that pertain to the concept of active ageing promoted through commitment 2. Ensuring participation of older people in this area is a necessity for both institutions and companies, in particular in managing the effects of the extension of working life both on the production process and as a function of the mechanisms of intergenerational exchange and transmission of knowledge. |

| 7 Promotion of lifelong learning and adaptation of the educational system in response to economic, social and demographic changes | 6 | 4 | Poor levels of education can have negative repercussions throughout the life span, becoming an obstacle to the pursuit of healthy and active ageing. The theme of education and learning also has a considerable impact on other important dimensions. For example, that of income (as low education is generally correlated with low income), with direct repercussions on the type of work performed, on the state of health and on the quality of life. |

| 8 To promote initiatives to ensure quality of life, independence, health and well-being. | 7 | 3 | Health and quality of life are key elements in the field of active ageing, which, as a result, contribute to obtaining positive feedback in this sense, so that benefits in terms of health and quality of life are also enjoyed by people with a health deficit. On the other hand, greater health problems imply greater problems in accessing active ageing. |

| 9 Enhancement of the gender approach in a society characterized by demographic ageing | 8 | 5 | The issue of the gender approach, highly regarded by MIPAA and the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development, can be considered as a specific declination of the more general problem of inequalities. |

| 10 To support families providing care to older people and to promote intergenerational solidarity | 9 | 16 | Support provided to families, in relation to care activities, should be not only a responsibility of the governmental bodies that provides these services, but also of the community in general, with a view to solidarity. To consider the life cycle perspective is critical for several reasons. Therefore, it is also necessary to think about active ageing to prepare future generations to face old age in the best possible way. |

| 11 Sustainable cities | 11 | In order to guarantee to older people access to all the opportunities for active ageing, it is important to consider the methods of access to the services and active ageing paths which are present in the area, in terms of organization of transports, adequacy of housing and infrastructure. | |

| 12 Cooperation for the promotion and full realization of the Regional Strategy for the implementation of the MIPAA | 10 | The strategy for the implementation of the MIPAA (Regional Implementation Strategy—RIS) consists in making sure that everything that has been discussed through the previous points is concretely realized. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lucantoni, D.; Principi, A.; Socci, M.; Zannella, M.; Barbabella, F. Active Ageing in Italy: An Evidence-Based Model to Provide Recommendations for Policy Making and Policy Implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052746

Lucantoni D, Principi A, Socci M, Zannella M, Barbabella F. Active Ageing in Italy: An Evidence-Based Model to Provide Recommendations for Policy Making and Policy Implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052746

Chicago/Turabian StyleLucantoni, Davide, Andrea Principi, Marco Socci, Marina Zannella, and Francesco Barbabella. 2022. "Active Ageing in Italy: An Evidence-Based Model to Provide Recommendations for Policy Making and Policy Implementation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052746

APA StyleLucantoni, D., Principi, A., Socci, M., Zannella, M., & Barbabella, F. (2022). Active Ageing in Italy: An Evidence-Based Model to Provide Recommendations for Policy Making and Policy Implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052746