Proposal of a Comprehensive and Multi-Component Approach to Promote Physical Activity among Japanese Office Workers: A Qualitative Focus Group Interview Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Recruitments

2.2. Focus Group Interview and Survey

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Topic 1 Analysis

3.2.1. Individual Factors

G: As I get older, I start to feel that I have various physical problems. I think it is important to maintain sufficient physical activity to extend my life expectancy as much as possible. (Age)

A: I do not want to move my body because I have a chronic disease. I do not want to be forced to do physical activities. (Biological health)C: I feel the importance of moving my body during remote work because it is too sedentary and leads to pain in the back and shoulder. However, I feel fine when commuting to work, so I think physical activity is important. (Biological health)

F: Rather than going out (exercising) to release stress, it is more often the case that we go to drink to complain each other. (Stress)D: It’s not in my nature to sit for a long time, so I often go to the print room to take a printout when sitting for over 1 h. (Personality)G: I am a restless person, so I am conscious of standing up, stretching my back, or going to the print room to take a printout frequently. (Personality)B: Usually, when I am in the office, I use the stairs as much as possible. Once an hour, I stand up from my seat or walk in the hallway to move my body. (Habit)G: Because I want to keep my body moving, I try to use stairs or walk every day instead of using escalators. (Habit)C: I understand that it is important to improve physical activity, but it is not realistic. (Attitude)E: I walk to lose weight or prepare for a disaster such as an earthquake (walking when the train stops due to a major earthquake), but I do not focus on increasing physical activity for its own sake.D: In my opinion, exercise means running or kicking a ball. When I tried to alight one stop early on the commute for a walk, I did not feel any good changes in my body. In particular, because of not reducing my weight, I think exercise is not effective without high intensity. (Belief)D: I am not familiar with the term “physical activity.” It does not seem to be an alternative to exercise. (Knowledge)E: Since I started yoga, I realized that my back muscles get stiff after long sitting. So, I get up to stretch. (Experience)B: Because I love to move my body, I prefer using the stairs rather than the escalators on my way to work. I also go trekking or exercise on weekends because I enjoy it. (Preference)

3.2.2. Socio-Cultural Environment Factors

C: I live with my husband. When the first state of emergency was announced, we took a walk along the river, which is located around my home. When he was lazy, I invited him to take a walk with me. If he was working out, I thought I had to do it too, so I did it with him. When my husband does something, it stimulates me. (Family)B: In my family, I am the most physically active. Sometimes, I propose that my wife walk, but she is lazy and does not want to do it. So, it is hard to promote physical activity to her.” (Family)G: When my child was young, I used to do a catch ball. I still take a walk with my wife occasionally. She sometimes recommends cycling when I am lazy. (Family)B: I play soccer with younger people in my town once every two weeks. (Peers)G: We do not exercise with my colleagues, so we are not affected by each other. Sometimes, there is a conversation about healthy behaviors such as alighting one stop early on the commute for a walk. (Colleagues)F: Our most colleagues are consultants. We almost always work alone than work as a team, so we do not have the opportunity to exercise together. (Colleagues)

3.2.3. Physical Environment Factors

G: COVID 19 deprived us of the opportunity to exercise with our family. (COVID-19)F: Now I cannot go to the gym because of COVID-19. I felt well when I moved my body. (COVID-19)E: I used to walk 200,000 steps a month, but in April and May (the state of emergency), I only walked 70,000 steps. I felt that daily physical activities such as commuting are crucial. (COVID-19)A: The river flows from my house to the nearest station. When cherry blossoms bloom, I take a walk with my wife. Just during this season, I become active. (Weather)

F: In my case, I have a lot of desk-based work. (Work environment)G: My job is desk-based. Because I sit down for a long time, my back hurts a little. (Work environment)A: I do not have any interest in walking around my house or workplace. (Environment around the workplace)C: There is a green space around the office. I feel grateful because I can see seasonal flower blooms when I commute or go out. (Environment around the workplace)D: There is a green space around the office, but the roads are messy. In my first days at this company, I tried to run around the office; however, I was stopped by traffic lights many times. There were a lot of people around the worksite, and I thought it was difficult to run. (Environment around the workplace)B: I moved to the suburbs 30 years ago because l like the sea and green space and wanted to get some rest on the weekend. There are many good places to walk near my house. (Residential environment)C: There is a waterfowl habitat near my house (a five-minute walk), where pheasants live and I can hear their yelling. Furthermore, the sidewalks are wide, and the roads are well-maintained. I think it is a very good running environment. (Residential environment)F: The sidewalk around my house is quite narrow. Therefore, it was difficult to walk along the sidewalk when my kids are little because of many vehicles. (Residential environment)A: My main stress was commuting, which takes an hour and a half one-way. However, after the shift to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic, this stress is relieved. I think reducing commuting time is more crucial for my health than doing exercise or reducing sitting time. (Commuting)

3.2.4. Organizational Factors

B: I think that our company has introduced various health promotion programs compared with other companies. However, it seems that only a few employees participated in these programs. In addition to physical activity promotion, there may be various programs, such as yoga and sports. (Policy)A: I think the current status is nice, because I just have to choose from various health promotion programs. If the company forces us to do something, I will strongly oppose. (Policy)D: I know there are many health promotion programs introduced by the company, but I do not participate in these programs. (Policy)

E: I am so busy with my work, and it is a priority for me. Therefore, I have not participated in any health promotion programs. (Work–life balance)C: In the workplace, I think that I must focus on my work rather than spend time on myself, which participation in health promotion programs entails. (Work–life balance)

3.3. Topic 2 Analysis

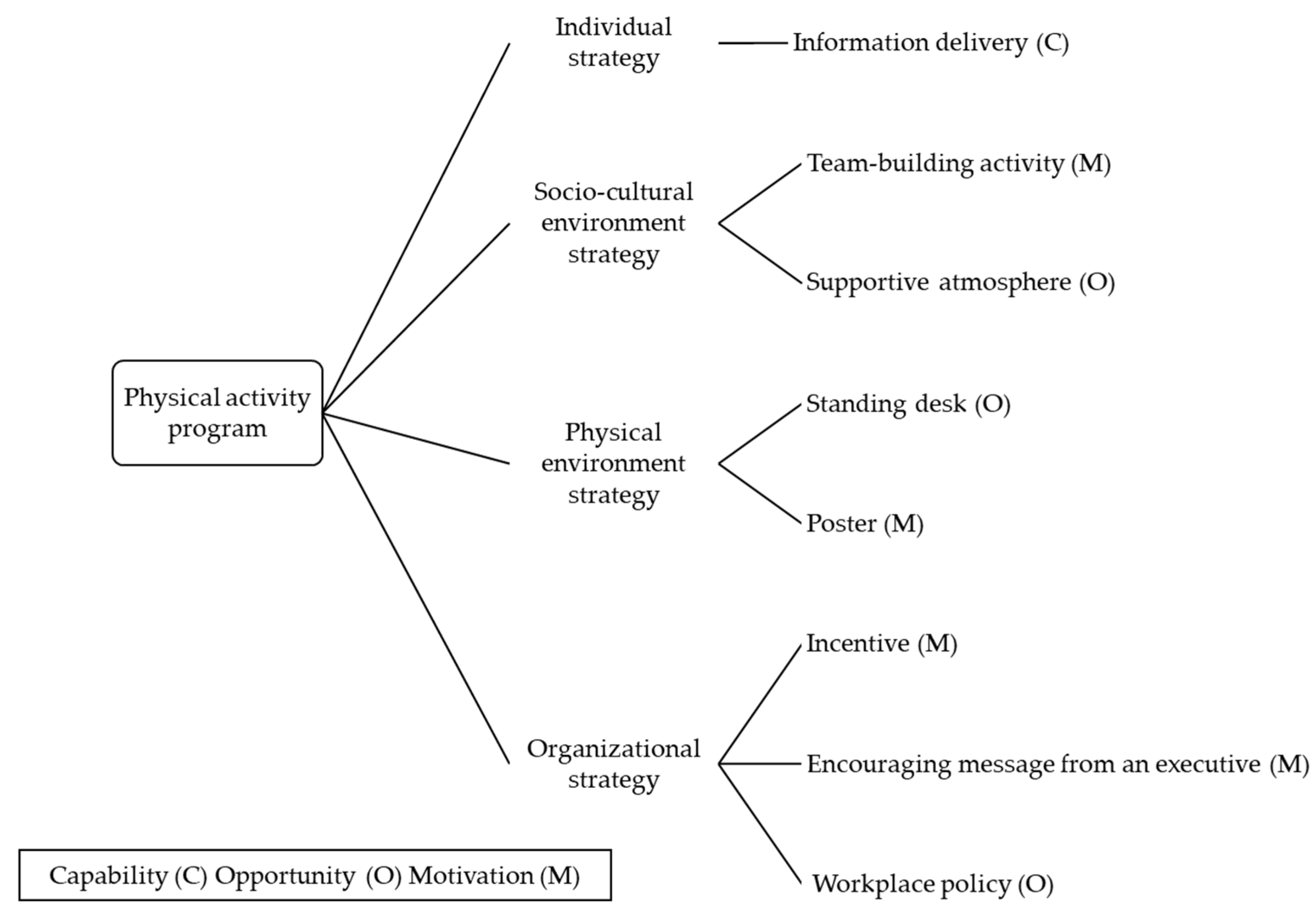

3.3.1. Capability Factors

A: I want evidence-based information associated with health. Furthermore, when offering information, it may be helpful to explain the mechanism of health benefits to the employee because they already have basic knowledge on health.” (Education)

3.3.2. Opportunity Factors

D: I think it is good to install a shower room or locker in this building. When I walk to the office after getting off one station earlier, I am drenched in sweat. (Environmental restructuring)E: If physical activity can be improved by simply shifting from sitting to standing while working, a conference room with a standing table or a movable sit/stand desk could be useful. (Environmental restructuring)G: It will be effective to set some constraints, such as environmental restructuring on the company in the medium term. (Enablement)

A: Our division head is not an active person but is interested in new information. Our group leader takes initiative and acts. Therefore, our team is very active and motivated. (Environmental restructuring)B: I think that it is necessary to create an office culture that allows employees to move without hesitation such as moving their shoulders in circles and standing up. (Environmental restructuring)E: There is nothing better than encouraging messages (close to command) from an executive. However, it is also difficult to establish an office culture. (Restriction)

3.3.3. Motivation Factors

C: I think poster pop, which is attached near the printer, is useful to promote physical activity during the use of the printer. (Persuasion)F: The recommendation from the superior may be effective. Like “Let’s take a break or reduce overtime work”, it would be nice to declare “Let’s make a move.” (Persuasion)E: Incentives may be a very effective strategy for promoting physical activity with immediate and sustainable effects. We may be satisfied if we can select an incentive as we want from many types, such as money, gift certificates, book cards, or points. (Incentivization)F: Working reform, which is reducing overtime work by switching off their computer and office if the specified time is exceeded, is progressing. Although there are many opinions on this, we will get used to the company policy. (Coercion)

C: Incentive compensation by interlocking their daily step count may be effective. However, if they do not receive the incentives they want, they may quit. Sometimes, they may find being physically active to be fun. (Incentivization)C: If the amount of physical activity is incorporated into the employees’ performance assessment, I think all employees will participate in improving physical activity. But I think it is a big no-no by Japanese culture. (Modelling)B: If we aim to improve the level of physical activity at our company, why do we not give incentives to groups that achieve sufficient physical activity by group-based competition? (Modelling)

3.4. Comprehensive and Multi-Component Intervention Program

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets of Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity/en/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Active Guide—Japanese Official Physical Activity Guidelines for Health Promotion. Available online: https://www.nibiohn.go.jp/eiken/programs/pdf/active2013-e.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity from 2001 to 2016: A Pooled Analysis of 358 Population-Based Surveys with 1·9 Million Participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2019. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/eiyou/r1-houkoku_00002.html (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/physical-activity#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Choi, B.; Schnall, P.L.; Yang, H.; Dobson, M.; Landsbergis, P.; Israel, L.; Karasek, R.; Baker, D. Sedentary Work, Low Physical Job Demand, and Obesity in US Workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Uffelen, J.G.; Wong, J.; Chau, J.Y.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Riphagen, I.; Gilson, N.D.; Burton, N.W.; Healy, G.N.; Thorp, A.A.; Clark, B.K.; et al. Occupational Sitting and Health Risks: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prince, S.A.; Elliott, C.G.; Scott, K.; Visintini, S.; Reed, J.L. Device-Measured Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Cardiometabolic Health and Fitness Across Occupational Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen, J.M.; Proper, K.I.; van Wier, M.F.; van der Beek, A.J.; Bongers, P.M.; van Mechelen, W.; van Tulder, M.W. A Systematic Review of the Cost-Effectiveness of Worksite Physical Activity and/or Nutrition Programs. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2012, 38, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watanabe, K.; Kawakami, N. Effects of a Multi-Component Workplace Intervention Program with Environmental Changes on Physical Activity Among Japanese White-Collar Employees: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 25, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, G.N.; Eakin, E.G.; Owen, N.; Lamontagne, A.D.; Moodie, M.; Winkler, E.A.; Fjeldsoe, B.S.; Wiesner, G.; Willenberg, L.; Dunstan, D.W. A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Reduce Office Workers’ Sitting Time: Effect on Activity Outcomes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, G.N.; Winkler, E.A.H.; Eakin, E.G.; Owen, N.; Lamontagne, A.D.; Moodie, M.; Dunstan, D.W. A Cluster RCT to Reduce Workers’ Sitting Time: Impact on Cardiometabolic Biomarkers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.; Mullane, S.L.; Toledo, M.J.L.; Larouche, M.L.; Rydell, S.A.; Vuong, B.; Feltes, L.H.; Mitchell, N.R.; de Brito, J.N.; Hasanaj, K.; et al. Efficacy of the ‘Stand and Move at Work’ Multicomponent Workplace Intervention to Reduce Sedentary Time and Improve Cardiometabolic Risk: A Group Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirathananuwat, A.; Pongpirul, K. Promoting Physical Activity in the Workplace: A Systematic Meta-Review. J. Occup. Health 2017, 59, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, A.H.; Ng, S.H.; Tan, C.S.; Win, A.M.; Koh, D.; Müller-Riemenschneider, F. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Workplace Intervention Strategies to Reduce Sedentary Time in White-Collar Workers. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredahl, T.V.; Særvoll, C.A.; Kirkelund, L.; Sjøgaard, G.; Andersen, L.L. When Intervention Meets Organisation, a Qualitative Study of Motivation and Barriers to Physical Exercise at the Workplace. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 518561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, K.C.; Michl, G.L.; Katz, J.N.; Losina, E. Meteorologic and Geographic Barriers to Physical Activity in a Workplace Wellness Program. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevitz, K.; Dement, J.; Schoenfisch, A.; Joyner, J.; Clancy, S.M.; Stroo, M.; Østbye, T. Perceived Barriers to Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Among Participants in a Workplace Obesity Intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.; Murphy, R.; Shepherd, S.; Graves, L. Multi-Stakeholder Perspectives of Factors That Influence Contact Centre Call Agents’ Workplace Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olsen, H.M.; Brown, W.J.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Burton, N.W. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in a flexible office-based workplace: Employee perceptions and priorities for change. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2018, 29, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Kasteren, Y.F.; Lewis, L.K.; Maeder, A. Office-Based Physical Activity: Mapping a Social Ecological Model Approach Against COM-B. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E.B. Ecological Models of Health Behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 465–485. ISBN 978-0-7879-9614-7. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A New Method for Characterising and Designing Behaviour Change Interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Kenko Keiei. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/kenko_keiei.html (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Laine, J.; Kuvaja-Köllner, V.; Pietilä, E.; Koivuneva, M.; Valtonen, H.; Kankaanpää, E. Cost-Effectiveness of Population-Level Physical Activity Interventions: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 29, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Klepp, K.I.; Sjöstrand, J. Development of a Health Education Programme for Elderly with Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Focus Group Study. Patient Educ. Couns. 1998, 34, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, S.E.; Jackson, B.R.; Edwardson, C.L.; Yates, T.; Biddle, S.J.; Davies, M.J.; Dunstan, D.; Esliger, D.; Gray, L.; Miller, P.; et al. Providing NHS Staff with Height-Adjustable Workstations and Behaviour Change Strategies to Reduce Workplace Sitting Time: Protocol for the Stand More AT (SMArT) Work Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bull, F.C.; Maslin, T.S.; Armstrong, T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): Nine country reliability and validity study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2009, 6, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwardson, C.L.; Yates, T.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Davies, M.J.; Dunstan, D.W.; Esliger, D.W.; Gray, L.J.; Jackson, B.; O’Connell, S.E.; Waheed, G.; et al. Effectiveness of the Stand More AT (SMArT) Work Intervention: Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2018, 363, k3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McPhee, J.S.; French, D.P.; Jackson, D.; Nazroo, J.; Pendleton, N.; Degens, H. Physical Activity in Older Age: Perspectives for Healthy Ageing and Frailty. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Omar, K.; Rütten, A.; Robine, J.M. Self-Rated Health and Physical Activity in the European Union. Soz. Praventivmed. 2004, 49, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortis, C.; Puggina, A.; Pesce, C.; Aleksovska, K.; Buck, C.; Burns, C.; Cardon, G.; Carlin, A.; Simon, C.; Ciarapica, D.; et al. Psychological Determinants of Physical Activity across the Life Course: A “DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity” (DEDIPAC) Umbrella Systematic Literature Review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, L.K.; Godino, J.G.; Selvin, E.; Kucharska-Newton, A.; Coresh, J.; Koton, S. Spousal Influence on Physical Activity in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: The ARIC Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 183, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarkar, S.; Taylor, W.C.; Lai, D.; Shegog, R.; Paxton, R.J. Social Support for Physical Activity: Comparison of Family, Friends, and Coworkers. Work 2016, 55, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tison, G.H.; Avram, R.; Kuhar, P.; Abreau, S.; Marcus, G.M.; Pletcher, M.J.; Olgin, J.E. Worldwide Effect of COVID-19 on Physical Activity: A Descriptive Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, P.; Gilliland, J. The Effect of Season and Weather on Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Public Health 2007, 121, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlakha, D.; Hipp, A.J.; Marx, C.; Yang, L.; Tabak, R.; Dodson, E.A.; Brownson, R.C. Home and Workplace Built Environment Supports for Physical Activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 48, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saelens, B.E.; Vernez Moudon, A.; Kang, B.; Hurvitz, P.M.; Zhou, C. Relation Between Higher Physical Activity and Public Transit Use. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, R.G.; Hipp, J.A.; Marx, C.M.; Brownson, R.C. Workplace Social and Organizational Environments and Healthy-Weight Behaviors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.A.; Gazmararian, J. The Association Between Long Work Hours and Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Obesity. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 10, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.H.; Blake, H.; Suggs, L.S. A Systematic Review of Workplace Health Promotion Interventions for Increasing Physical Activity. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 149–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr-Anderson, D.J.; AuYoung, M.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Glenn, B.A.; Yancey, A.K. Integration of Short Bouts of Physical Activity into Organizational Routine a Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Hunter, R.F.; Maple, J.L.; Moodie, M.; Salmon, J.; Ong, K.L.; Stephens, L.D.; Jackson, M.; Crawford, D. Can an Incentive-Based Intervention Increase Physical Activity and Reduce Sitting Among Adults? The ACHIEVE (Active Choices IncEntiVE) Feasibility Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, M.S.; Volpp, K.G.; Rosin, R.; Bellamy, S.L.; Small, D.S.; Heuer, J.; Sproat, S.; Hyson, C.; Haff, N.; Lee, S.M.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Lottery-Based Financial Incentives to Increase Physical Activity Among Overweight and Obese Adults. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1568–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Designing and Conducting Focus Group Interviews. Available online: https://www.eiu.edu/ihec/Krueger-FocusGroupInterviews.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

| Variables | Participants (n = 7) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

| Job position | RG | RG | RG | RG | RG | MG | MG |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male |

| Age (years) | 57 | 62 | 39 | 48 | 42 | 47 | 53 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.0 | 22.7 | 21.4 | 24.6 | 20.2 | 28.7 | 21.1 |

| Education level | UG | UG | UG | UG | UG | UG | UG |

| Continuous years of service | 39 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 23 | 31 |

| Self-reported physical activity | |||||||

| Overall MVPA (min/week) | 270 | 1080 | 365 | 410 | 335 | 210 | 180 |

| Occupational MVPA (min/week) | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Transport-related MVPA (min/week) | 270 | 420 | 165 | 50 | 175 | 150 | 120 |

| Leisure-time MVPA (min/week) | 0 | 660 | 150 | 360 | 150 | 60 | 60 |

| Sitting time (min/day) | 720 | 300 | 300 | 540 | 540 | 510 | 600 |

| Factors | Categories | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Demographic | Age |

| Biological | Biological health | |

| Psychological | Stress | |

| Personality | ||

| Habit | ||

| Attitude | ||

| Beliefs | ||

| Knowledge | ||

| Experience | ||

| Preference | ||

| Socio-cultural environment | Social networks | Family |

| Peers | ||

| Colleagues | ||

| Physical environment | Natural environment | COVID-19 |

| Weather | ||

| Built environment | Work environment | |

| Environment around workplace | ||

| Residential environment | ||

| Commuting | ||

| Organizational | Policy | Policy |

| Organizational culture | Work–life balance |

| Factors | Categories | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Capability | Psychological | Education |

| Opportunity | Physical | Environmental restructuring |

| Enablement | ||

| Social | Environmental restructuring | |

| Restriction | ||

| Motivation | Reflective | Persuasion |

| Incentivization | ||

| Coercion | ||

| Automatic | Incentivization | |

| Modelling |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Mizushima, R.; Nishida, K.; Morimoto, M.; Nakata, Y. Proposal of a Comprehensive and Multi-Component Approach to Promote Physical Activity among Japanese Office Workers: A Qualitative Focus Group Interview Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042172

Kim J, Mizushima R, Nishida K, Morimoto M, Nakata Y. Proposal of a Comprehensive and Multi-Component Approach to Promote Physical Activity among Japanese Office Workers: A Qualitative Focus Group Interview Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042172

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jihoon, Ryoko Mizushima, Kotaro Nishida, Masahiro Morimoto, and Yoshio Nakata. 2022. "Proposal of a Comprehensive and Multi-Component Approach to Promote Physical Activity among Japanese Office Workers: A Qualitative Focus Group Interview Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042172

APA StyleKim, J., Mizushima, R., Nishida, K., Morimoto, M., & Nakata, Y. (2022). Proposal of a Comprehensive and Multi-Component Approach to Promote Physical Activity among Japanese Office Workers: A Qualitative Focus Group Interview Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042172