The Importance of Place Attachment in the Understanding of Ageing in Place: “The Stones Know Me”

Abstract

1. Introduction—A Place of My Own: Why Ageing in Place Is Important in the Construct and Experience of Ageing

1.1. Ageing in Place

1.2. Place Attachment

1.3. Place Attachment in the Urban Environment

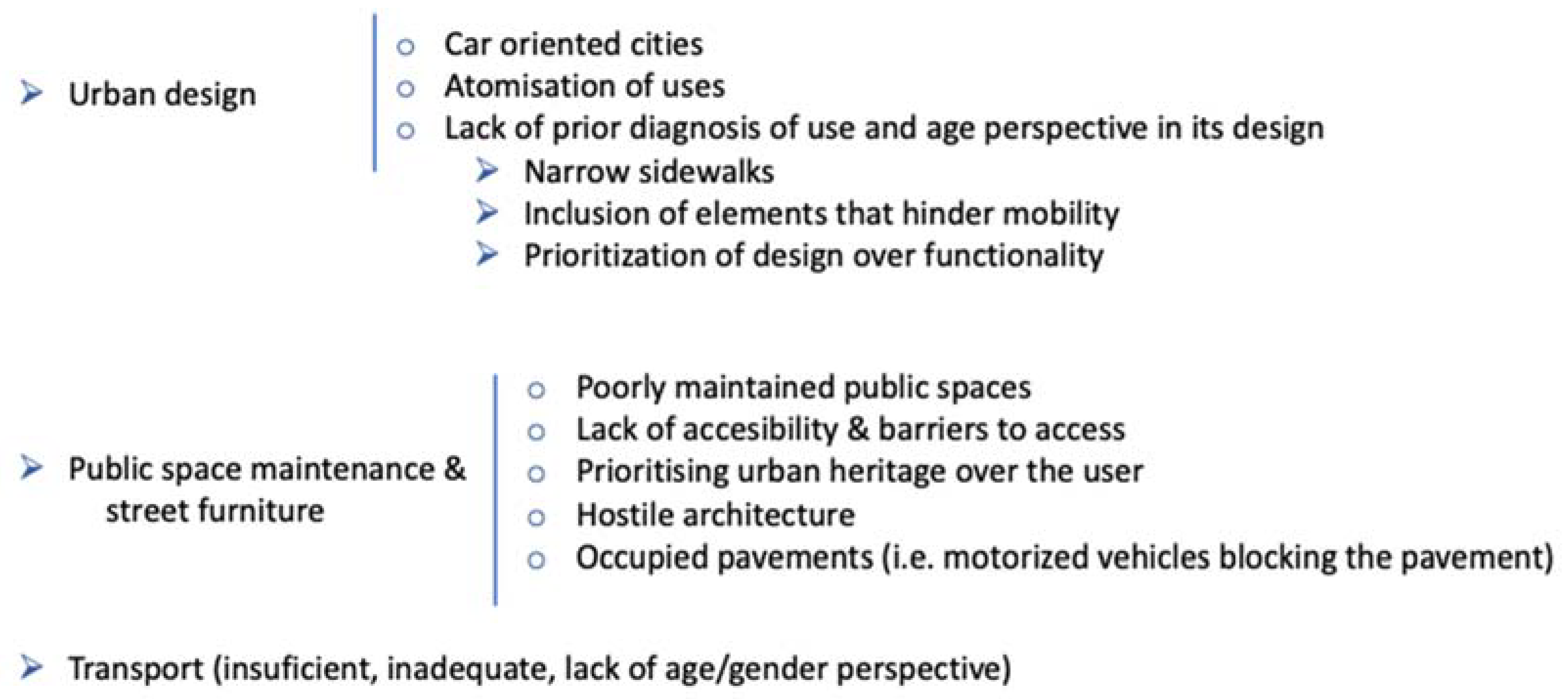

1.4. Political Implications. Obstacles and Challenges in Achieving Age-Friendly Neighbourhoods

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. What Ageing in Place Means—The Life Experience and Attachment

“I love my neighbourhood, and I’ve been here for 50 years, so I’m staying here”.EM15 (68 years old).

“If I won the lottery, I would never leave my house, I don’t know why… Because I like it, I like it. I like it (…) It’s probably because I’ve lived there for a long time. But no, no, I never wanted to leave”.EM11 (68 years old).

“Of course, I consider myself old when I have to climb to clean the windows… I can’t do it anymore. That’s because I also get dizzy. So I need someone to do the windows for me, to do a general cleaning”.EM12 (73 years old).

“I like the neighbourhood (…) I wouldn’t, I wouldn’t go anywhere else. (…) We haven’t been able to put a lift in. I live on the second floor, so I have to go up and down. The day I can’t, I’ll put up with it”.EM30 (87 years old).

“Look, I have a flat in Villalba. It is very nice. Nicer than this one because this is a fourth floor without a lift. You can get an idea, 90 steps. Well, I don’t know. I go out, I think I have… the stones know me, I go out and… It’s not that I’m out of my mind, no. It’s that I like the neighbourhood more than anything else”.EM31 (86 years old).

“I like to be independent. As long as I can (…) I would like to continue living, taking care of myself”.EM4 (65 years old).

“I tell you one thing, I wouldn’t sell my flat for anything because right now (…) never, I wouldn’t sell my flat for anything in the world, for nothing. I wouldn’t, this is my final home, until I die”.EM9 (65 years old).

“As soon as you retire, you yourself think that you are no longer good for anything”.EM1 (82 years old).

“In the swimming pool there is only one man of our average age. In the previous group, none. (…) We, women, go much more to all the things… They play cards with each other. Yes. They go to petanque, yes. But then they don’t go to these centres to… They are ashamed or I don’t know why they don’t go”.EM32 (70 years old).

“I think that the adaptation of men when they stop working has nothing to do with us”.EM35 (71 years old).

“I retired two years ago, but I had been working for many years before that, with many activities, preparing for my retirement. And yet men finish working and it’s a step where they don’t know what to do. How do I fill my time, what do I do with my life? If they’re not attached to the missus… you must rely on them a lot. In general, right?”EM33 (67 years old).

“Oh, in my opinion, I’ve never been old. Because they always say “Look, poor woman, how old she is” and you say “But you have looked at yourself, what you are? “Oh, you’re… I don’t know how old you are, oh poor thing and so on”. “Oh, how she walks” and she says: “But you don’t consider yourself old” “Oh no, I don’t consider myself old”. [That was in the past]. And now I say, “Oh yes, I’m already very old, I’m already very old” (she laughs). You can no longer do the things you do, of course. But I’ve run the house. Everything, everything, everything, all the chores, and I’ve been doing everything, everything, everything. All the meals… well, an assistant comes once a week and she cleans everything for me, but the rest of everything, the ironing… Everything (…) I’ve taken care of. Well, that’s probably why I didn’t consider myself… I was still valid”.EM5 (85 years old).

“I see myself today as an old person who cannot do with my life what I want to do, because I don’t have the means to do it. So… (…). You can also be an old person like my mother was [she suffered a stroke], you can be left in that way that you depend on a lot of other people. Right now, let’s see, [Isabel] Preysler [socialité] is 71 years old and nobody tells Preysler that she is old”.EM4 (65 years old).

3.2. The Subjective Construction of the Neighbourhood

“Yes, this is the best neighbourhood here, the best place, the best area. We are left to our own devices, but… Yes, this is the best neighbourhood there is”.EM16 (68 years old).

“My sisters, one lives in [name of neighbourhood] and the other in [name of neighbourhood], in some new houses they built there. What a difference! We used to come here, and this was “life”. Here you always see people in the street. (…) And I like meeting people. And not [being] in a lonely neighbourhood, which is where you can get scared”.EM34 (77 years old).

3.3. How Is Place Attachment Constructed? Influencing Factors

3.3.1. History and Family

“My brother came, then my mother and then we came. My children also live nearby”.EM6 (66 years old).

“We bought a flat near my mother-in-law (…) she lives a few streets away, on her own (…) she is 92 years old. Before, she used to come by herself to eat, but now she has to be picked up by car (…) and she comes every day to eat”.EM19 (67 years old).

“My husband was born in this house. And it [the neighbourhood] attracted him a lot. And my mother-in-law said: “Well, come here”. My children have grown up here, in this neighbourhood (…) I like everything about the neighbourhood (…) I like, that’s why I tell you: I like everything about the neighbourhood”.EM34 (77 years old).

“My youngest son was born here. The older ones weren’t, but they came when they were very little. And so, there’s still that warmth, isn’t there? And… I don’t know. There is still the warmth of the family, and of the children and so on”.EM8 (65 years old).

3.3.2. Recognition and Identification

“I’m so happy in my house and everything, in my neighbourhood. Do you know what it’s like to go out on the street and bye-bye! Hello! Everyone knows me here: How are you, how are you? I was born here!”.EM24 (67 years old).

“I am very happy. Because there are many activities, you meet many people, you talk to many classmates… So, I am very happy. Yes, yes, yes, yes (…) So, very good. And I tell you, I am very happy here [local community center], that’s the truth”.EM36 (68 years old).

“Yes, because here all the neighbours have always known each other”.EM10 (92 years old).

“Yes, yes, we know each other. All the old people know each other. When one of us dies, I say: “Oh, what a pity”. Of course, if it’s… Of course, this neighbourhood is not a neighbourhood, this neighbourhood is a village”.EM37 (66 years old).

3.3.3. Ontological Security and Microgroup Solidarity

“I feel at ease, I am in my shelter”.EM25 (70 years old).

“I want my neighbourhood because I know a lot of people here. We all know each other, we all know where we all stand, we all know where I stand, and we all know each other”.EM15 (68 years old).

“Many times, I go by myself. (…) I don’t have prejudices. I deal with my butcher, with my greengrocer, whose name is Julito (…) And I have other friends that we see each other, we meet (…). They are acquaintances but we see each other. I have lived with them, and we still deal with each other”.EM 37 (66 years old).

“No one is living next to my door. The three years I’ve been here, that house is uninhabited, and nobody live in it (..) If anything happens to you, you go out there, you scream, whatever, but I have no one and I am panicked”.EM20 (75 years old).

“I liked the way it was before more than now (…) Well, we were all, as they say, as if we were family. The people from the neighbourhoods stayed longer, more people lived there, more time”.EM31 (86 years old).

“The neighbourhood has changed a lot. In terms of neighbourhood, I can tell you, for example, in my house before we were all… well, families. And, very close-knit families, that’s the truth, which is not the case now. That has been lost because now most of the apartments have been sold and are rented out”.EM36 (68 years old).

“They already know you in the neighbourhood. Because you can fall and say: “Look, [name] has fallen” … (…) “So-and-so, your mother is here” or “Mengano”, or whatever, or the neighbour who knows him. That is fundamental (…) Yes, because you need the support of the neighbourhood, and normally if you have lived there, you have friends in the neighbourhood because you know each other”.GD1 (65 years old).

“My neighbour Paquita has them [home keys], yes, and now I have hers”.EM31 (86 years old).

“The guy living up here, the one who left, used to bring it [the groceries] up to me. He left it for me here at the door, and we didn’t see each other or anything (…) Before that, I didn’t even know him or anything”.EM29 (77 years old).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- When ageing in place is mediated by place attachment, the associated sense of belonging mitigates the effect of the processes of rupture with respect to life experiences that can occur in old age with the change of roles associated with retirement and other life processes.

- -

- Ageing in place thus makes it possible to experience old age as a part of the life cycle, a stage that can be understood as an ongoing reality to which years are being added.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | AGE | GENDER | LEVEL OF EDUCATION | CIVIL STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM1 | 82 | MAN | No studies | Married |

| EM2 | 74 | MAN | Higher education | Widowed |

| EM3 | 89 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM4 | 65 | WOMAN | Elementary | Widow |

| EM5 | 85 | WOMAN | Higher education | Widow |

| EM6 | 66 | WOMAN | No studies | Married |

| EM7 | 95 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM8 | 65 | WOMAN | Higher education | Married |

| EM9 | 65 | WOMAN | No studies | Married |

| EM10 | 92 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM11 | 68 | WOMAN | No studies | Married |

| EM12 | 73 | WOMAN | Elementary | Married |

| EM13 | 83 | WOMAN | No studies | Divorced |

| EM14 | 90 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM15 | 66 | WOMAN | No studies | Single |

| EM16 | 68 | WOMAN | No studies | Married |

| EM17 | 71 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM18 | 69 | WOMAN | Higher education | Divorced |

| EM19 | 67 | WOMAN | Elementary | Widow |

| EM20 | 75 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM21 | 68 | WOMAN | Elementary | Single |

| EM22 | 82 | WOMAN | No studies | Married |

| EM24 | 67 | WOMAN | Elementary | Widow |

| EM25 | 70 | WOMAN | Elementary | Divorced |

| EM26 | 65 | WOMAN | Elementary | Married |

| EM27 | 84 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM28 | 94 | MAN | No studies | Widowed |

| EM29 | 77 | WOMAN | Elementary | Married |

| EM30 | 87 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| EM31 | 86 | WOMAN | Elementary | Divorced |

| EM32 | 70 | WOMAN | Secondary education | Single |

| EM33 | 67 | WOMAN | Higher education | Married |

| EM34 | 77 | WOMAN | Elementary | Widow |

| EM35 | 71 | WOMAN | Elementary | Married |

| EM36 | 68 | WOMAN | Elementary | Single |

| EM37 | 66 | WOMAN | Elementary | Divorced |

| ID | AGE | GENDER | ESTUDIOS | CIVIL STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD1 | 65 | MEN | Higher education | Married |

| GD2 | 65 | MEN | Higher education | Married |

| GD3 | 71 | WOMAN | No studies | Widow |

| GD4 | 69 | WOMAN | Higher education | Divorced |

| GD5 | 67 | WOMAN | Elementary | Widow |

References

- Costa-Font, J.; Elvira, D.; Mascarilla-Miró, O. Ageing in Place’? Exploring Elderly People’s Housing Preferences in Spain. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Carro, C.; Evandrou, M. Staying Put: Factors Associated with Ageing in One’s ‘Lifetime Home’. Insights from the European Context. Res. Ageing Soc. Policy 2014, 2, 28–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzón Pulido, S.A. Atención Residencial vs. Atención Domiciliaria En La Provisión de Cuidados de Larga Duración a Personas Mayores En Situación de Dependencia; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oldman, C. Deceiving, Theorizing and Self-Justification: A Critique of Independent Living. Crit. Soc. policy 2003, 23, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrusán, I. ¿No Es Ciudad Para Viejos?: Los ODS y La Experiencia de Envejecer En Las Ciudades Españolas. In Políticas Urbanas y localización de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: Teoría y Práctica; González Medina, M., De Gregorio Hurtado, S., Eds.; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2021; pp. 359–383. ISBN 978-84-1397-235-0. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J. How Long Can I Stay?: The Dilemma of Aging in Place in Assisted Living. In Assisted Living; Routledge: Londo, UK, 2014; pp. 5–30. ISBN 1315043793. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.K. Dictionary of Gerontology; Greenwood: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 0313252874. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.; Ajrouch, K. Sarah Hillcoat-Nallétamby Key Concepts in Social Gerontology; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978 1 4129 2272 2. [Google Scholar]

- Golant, S.M. The Quest for Residential Normalcy by Older Adults: Relocation but One Pathway. J. Aging Stud. 2011, 25, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausset, C.B.; Kelly, A.J.; Rogers, W.A.; Fisk, A.D. Challenges to Aging in Place: Understanding Home Maintenance Difficulties. J. Hous. Elderly 2011, 25, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, M.P. Aging and Performance of Home Tasks. Hum. Factors 1990, 32, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-González, D.; Rojo-Pérez, F.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G. Environmental and Psychosocial Interventions in Age-Friendly Communities and Active Ageing: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynoos, J.; Nishita, C.; Perelma, L. Advancements in the Home Modification Field: A Tribute to M. Powell Lawton. J. Hous. Elderly 2003, 17, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the Aging Process. In The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, A.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Beridze, G.; Teixeira, L.; Araújo, L.; Rojo-Pérez, F.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Quirós-González, V.; et al. Influence of Active and Healthy Ageing on Quality of Life Changes: Insights from the Comparison of Three European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrusán Murillo, I. La Vivienda En La Vejez; Colección.; Editorial CSIC Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 9788400105471. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in Urban Environments: Developing ‘Age-Friendly’ Cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roizblatt, A.; Corón, M.; Verdugo, R.; Erazo, C.; Miño, V. Familia, Vivienda y Medio Ambiente: Algunos Aspectos Psicosociales. APAL, Chile 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrusán Murillo, I. La Vivienda En La Vejez: Problemas y Estrategias Para Envejecer En Sociedad. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, F.S.; Oldman, C.; Means, R. Housing and Home in Later Life; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2002; ISBN 0335201695. [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard, C.; Hyde, M.; Higgs, P. The Impact of Age, Place, Aging in Place, and Attachment to Place on the Well-Being of the over 50s in England. Res. Aging 2007, 29, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Perez, F.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, V.; Molina-Martinez, M.A.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, D.; Rojo-Abuin, J.M.; Ayala, A.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Calderon-Larrañaga, A.; Ribeiro, O.; et al. Active Ageing Profiles among Older Adults in Spain: A Multivariate Analysis Based on SHARE Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo-Pérez, F. Entorno Residencial y Factores Asociados En El Marco Del Envejecimiento Activo. In Envejecimiento Activo, Calidad de Vida y Género. Las Miradas Académica, Institucional y Social; Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, P.H.; Oberlink, M.R. Developing Community Indicators to Promote the Health and Well-Being of Older People. Fam. Community Health 2003, 26, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Place: An Experiential Perspective. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistoni, S.S.T. Gerontologia Ambiental: Panorama de Suas Contribuições Para a Atuação Do Gerontólogo. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. e Gerontol. 2014, 17, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izal, M.; Fernández-Ballesteros, R. Modelos Ambientales Sobre La Vejez. An. Psicol. Psychol. 1990, 6, 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, H.-W. Environmental Influences on Aging and Behavior. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging; Birren, J.E., Schaie, K.W., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, R.I.; Parmelee, P.A. Attachment to Place and the Representation of the Life Course by the Elderly. Place Attach. 1992, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burholt, V.; Naylor, D. The Relationship between Rural Community Type and Attachment to Place for Older People Living in North Wales, UK. Eur. J. Ageing 2005, 2, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.E. Processes of Place Attachment: An Interactional Framework: Processes of Place Attachment. Symb. Interact. 2015, 38, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M. The City and Self-Identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-Identity: Physical World Socialization of the Self (1983). In The People, Place, and Space Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 77–81. ISBN 1315816857. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, S.; Pol, E. El Concepto de Identidad Social Urbana: Una Aproximación Entre La Psicología Social y La Psicología Ambiental. Anu. Psicol. UB J. Psychol. 1994, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, S. Cities as Social Representations. In Social Representations; Farr, R.M., Moscovici, S., Eds.; Editorial Advisory Board: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 1984; pp. 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. La Memoria Colectiva; Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rowles, G.D. Evolving Images of Place in Aging and’aging in Place’. Gener. J. Am. Soc. Aging 1993, 17, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, F.; Kaspar, R. On the Quantitative Assessment of Perceived Housing in Later Life. In Environmental Gerontology; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 93–114. ISBN 1315873303. [Google Scholar]

- Peace, S.; Holland, C.; Kellaher, L. ‘Option Recognition’in Later Life: Variations in Ageing in Place. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 734–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, G.D.; Oswald, F.; Hunter, E.G. Interior Living Environments in Old Age. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2003, 23, 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rowles, G.D.; Watkins, J.F. History, Habit, Heart, and Hearth: On Making Spaces. Aging Indep. Living Arrange. Mobil. 2003, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Caradec, V. Sociologie de La Vieillesse et Du Vieillissement; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2004; ISBN 2200353391. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.; Walford, N.; Hockey, A. How Do Unfamiliar Environments Convey Meaning to Older People? Urban Dimensions of Placelessness and Attachment. Int. J. Ageing Later Life 2011, 6, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, M.H.; Fabian, A.; Kaminoff, R. Place-Identity: Physical World Socialization of the Self. i’Journal of Environmental Psychology. Nr. 3. Sidst set den 1983, 11, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, D. The Meaning of Housing: A Pathways Approach; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2005; ISBN 1861346379. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.V.; Lebrusán, I. Urban Ageing, Gender and the Value of the Local Environment: The Experience of Older Women in a Central Neighbourhood of Madrid, Spain. Land 2022, 11, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuurne (Ketokivi), K.; Gómez, M.V. Feeling at Home in the Neighborhood: Belonging, the House and the Plaza in Helsinki and Madrid. City Community 2019, 18, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place Attachment. In Place Attachment; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J. Doing Belonging: A Sociological Study of Belonging in Place as the Outcome of Social Practices. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-First Century The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scan. Polit. Stud. 2007, 30, 137–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostila, M. The Facets of Social Capital. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2011, 41, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 25, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, A.; Whitley, E.; Tannahill, C.; Ellaway, A. “lonesome town”? Is loneliness associated with the residential environment, including housing and neighborhood factors? J. Community Psychol 2015, 43, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blokland-Potters, T. Community as Urban Practice; Polity Press: Malden, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, L.H. The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 1315134357. [Google Scholar]

- Hedman, L. Moving Near Family? The Influence of Extended Family on Neighbourhood Choice in an Intra-Urban Context. Popul. Space Place 2013, 19, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, C.H.; Malmberg, G. Local Ties and Family Migration. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Sp. 2014, 46, 2195–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchezde Madariaga, I. Infraestructuras Para La Vida Cotidiana y Calidad de Vida. Ciudad. Rev. del Inst. Univ. Urbanística la Univ. Valladolid 2004, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinenberg, E. Palacios Del Pueblo. Políticas Para Una Sociedad Más Igualitaria; Capitan Swing: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.F.; Russell, A.; Powers, J.R. The Sense of Belonging to a Neighborhood: Can It Be Measured and Is It Related to Health and Well Being in Older Women? Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Flores, M.-E.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Forjaz, M.J.; Rojo-Perez, F.; Martinez-Martin, P. Residential Satisfaction, Sense of Belonging and Loneliness among Older Adults Living in the Community and in Care Facilities. Heal. Place 2011, 17, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Apóstolo, J. Envelhecimento, Saúde e Cidadania. Coimbra. Port. UICISA E 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lecovich, E. Aging in Place: From Theory to Practice. Anthropol. Noteb. 2014, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrusán, I. Las Dificultades Para Habitar En La Vejez. Available online: https://documentacionsocial.es/6/a-fondo/las-dificultades-para-habitar-en-la-vejez/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Phillipson, C. Developing Age-Friendly Communities: New Approaches to Growing Old in Urban Environments. In Handbook of the Sociology of Aging; Angel, J., Settersten, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, H.W.; Weisman, G.D. Environmental Gerontology at the Beginning of the New Millennium: Reflections on Its Historical, Empirical, and Theoretical Development. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities About Us-Age-Friendly World. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/about-us/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Lebrusán, I.; Toutouh, J. Smart City Tools to Evaluate Age-Healthy Environments. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 1359, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, E.; Gómez, M.V.; Higueras, E. Las Zonas Verdes y La Población Mayor En Madrid: Bienestar, Salud Mental e Inclusión. In Resiliencia: Espacios de Adaptación de Nuestras Ciudades a Los Nuevos Retos Urbanos; Hernández-Aja, A., Viedma, A., Díez, A., Eds.; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 19–36. ISBN 978-84-9728-596-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hashidate, H.; Shimada, H.; Fujisawa, Y.; Yatsunami, M. An Overview of Social Participation in Older Adults: Concepts and Assessments. Phys. Ther. Res. 2021, 24, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagestad, G.O.; Uhlenberg, P. Should We Be Concerned about Age Segregation? Some Theoretical and Empirical Explorations. Res. Aging 2006, 28, 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Kanaan, M.; Gilbody, S.; Ronzi, S.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Observational Studies. Heart 2016, 102, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtin, E.; Knapp, M. Social Isolation, Loneliness and Health in Old Age: A Scoping Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. Social Relationships and Health: The Toxic Effects of Perceived Social Isolation. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2014, 8, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Heitor, T.V.; Cabrita, A.R. Ageing Cities: Redesigning the Urban Space. In Proceedings of the CITTA 5th Annual Conference on Planning Research, Porto, Portugal, 18 May 2012; p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J. The Inclusive City: What Active Ageing Might Mean for Urban Design. In Proceedings of the Active Ageing: Myth or reality. Proceedings of the British Society of Gerontology 31st Annual Conference, Birmingham, UK, 12–14 September 2002; pp. 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora López, F.; Barrios, L.; Lebrusán Murillo, I.; Parant, A.; Delgado, M. Households of the Elderly in Spain: Between Solitude and Familiar Solidarities. In Ageing, Lifestyles and Economic Crisis: The New People of the Mediterranean; Blöss, T., Ed.; Rouletdge: New York, YK, USA, 2018; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrusán Murillo, I. Servicio Doméstico y Actividad de Cuidados En El Hogar: La Encrucijada Desde Lo Privado y Lo Público. Lex Soc. Rev. los derechos Soc. 2019, 9, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, P. Metodología de La Investigación; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Methodology. Case Study Research Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousan Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 076192552X. [Google Scholar]

- Valles, M.S. Entrevistas Cualitativas; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2002; ISBN 9788474763423. [Google Scholar]

- Valles, M.S. Técnicas Cualitativas de Investigación Social. Reflexión Metodológica y Práctica Profesional; Editorial Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 1999; ISBN 84-773-449-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, F.; Xue, S.; Wang, X. Amplitude of Low Frequency Fluctuations during Resting State Predicts Social Well-Being. Biol. Psychol. 2016, 118, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, P.F.; Foroughan, M.; Vedadhir, A.A.; Tabatabaei, M.G. The Effects of Place Attachment on Social Well-Being in Older Adults. Educ. Gerontol. 2016, 43, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bild, B.R.; Havighurst, R.J. Senior Citizens in Great Cities: The Case of Chicago. Gerontologist 1976, 16, 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tobio Soler, M.C.; Agulló Tomás, M.S.; Gómez García, M.V.P.; Martín Palomo, M.T. El Cuidado de Las Personas: Un Reto Para El Siglo XXI; Fundación “La Caixa”: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tobío, C. Estructura Urbana, Movilidad y Género En La Ciudad Moderna. In Proceedings of the Conferencia en la Escuela de Verano Jaime Vera, Galapagar, Madrid, Spain, June 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, J.T.; Moen, P. A Life-Course Perspective on Housing Expectations and Shifts in Late Midlife. Res. Aging 2000, 22, 499–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokland, T.; Nast, J. From Public Familiarity to Comfort Zone: The Relevance of Absent Ties for Belonging in Berlin’s Mixed Neighbourhoods. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lebrusán, I.; Gómez, M.V. The Importance of Place Attachment in the Understanding of Ageing in Place: “The Stones Know Me”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417052

Lebrusán I, Gómez MV. The Importance of Place Attachment in the Understanding of Ageing in Place: “The Stones Know Me”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):17052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417052

Chicago/Turabian StyleLebrusán, Irene, and M. Victoria Gómez. 2022. "The Importance of Place Attachment in the Understanding of Ageing in Place: “The Stones Know Me”" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 17052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417052

APA StyleLebrusán, I., & Gómez, M. V. (2022). The Importance of Place Attachment in the Understanding of Ageing in Place: “The Stones Know Me”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 17052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417052