Validity and Reliability of Questionnaires That Assess Barriers and Facilitators of Sedentary Behavior in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.2.1. List A

2.2.2. List B

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

3. Results

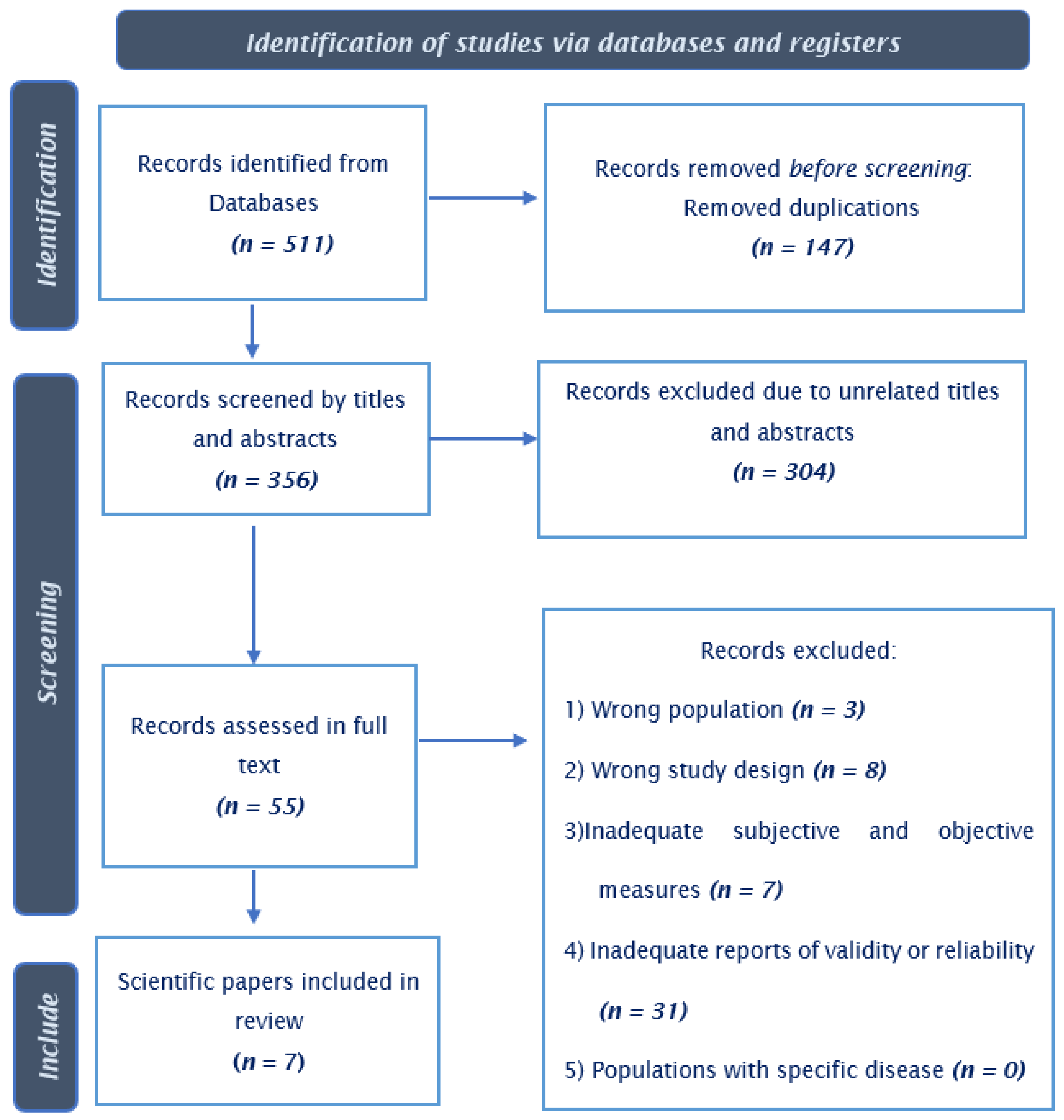

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics of Eligible Studies

3.2. Characteristics of Subjective Assessment Methods Recovered

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atkin, A.J.; Gorely, T.; Clemes, S.A.; Yates, T.; Edwardson, C.; Brage, S.; Salmon, J.; Marshall, S.J.; Biddle, S.J. Methods of Measurement in epidemiology: Sedentary Behaviour. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 1460–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prioreschi, A.; Brage, S.; Hesketh, K.D.; Hnatiuk, J.; Westgate, K.; Micklesfield, L.K. Describing objectively measured physical activity levels, patterns, and correlates in a cross sectional sample of infants and toddlers from South Africa. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Rankin, K.N.; Zuo, K.J.; Mackie, A.S. Computer-aided auscultation of murmurs in children: Evaluation of commercially available software. Cardiol. Young 2016, 26, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.; García Bengoechea, E.; Wiesner, G. Sedentary behaviour and adiposity in youth: A systematic review of reviews and analysis of causality. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rezende, L.F.; Rodrigues Lopes, M.; Rey-López, J.P.; Matsudo, V.K.; Luiz Odo, C. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes: An overview of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurt, R.T.; Kulisek, C.; Buchanan, L.A.; McClave, S.A. The obesity epidemic: Challenges, health initiatives, and implications for gastroenterologists. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 6, 780–792. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, M.M.; Agaronov, A.; Grytsenko, K.; Yeh, M.C. Intervening to Reduce Sedentary Behaviors and Childhood Obesity among School-Age Youth: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 685430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Kho, M.E.; Saunders, T.J.; Larouche, R.; Colley, R.C.; Goldfield, G.; Connor Gorber, S. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HW, K. Assessment of physical activity among childrenand adolescents: A review and synthesis. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, 54–76. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, P.H.; de Farias Júnior, J.C.; Florindo, A.A. Sedentary behavior in Brazilian children and adolescents: A systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 2016, 50, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.R.; Hesketh, K.; Cliff, D.P.; Barnett, L.M.; Salmon, J.; Dollman, J.; Morgan, P.J.; Hills, A.P.; Hardy, L.L. A systematic review of the validity and reliability of sedentary behaviour measures used with children and adolescents. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Onis, M.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kottner, J.; Audige, L.; Brorson, S.; Donner, A.; Gajewski, B.J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Roberts, C.; Shoukri, M.; Streiner, D.L. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, A.; Hales, D.; Ward, D.S. Measuring the physical activity practices used by parents of preschool children. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2013, 45, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, G.M.; Hardy, L.L.; Peat, J.K.; Baur, L.A. The validity and reliability of a home environment preschool-age physical activity questionnaire (Pre-PAQ). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, K.F.; Broffitt, B.; Levy, S.M. Validation evidence for the Netherlands physical activity questionnaire for young children: The Iowa Bone Development Study. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2005, 76, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, R.; Baranowski, T.; Watson, K.; Bachman, C.; Baranowski, J.C.; Thompson, D.; Hernández, A.E.; Venditti, E.; Blackshear, T.; Moe, E. Development of new physical activity and sedentary behavior change self-efficacy questionnaires using item response modeling. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Å.; Bohman, B.; Nyberg, G.; Schäfer Elinder, L. Psychometric Properties of a Scale to Assess Parental Self-Efficacy for Influencing Children’s Dietary, Physical Activity, Sedentary, and Screen Time Behaviors in Disadvantaged Areas. Health Educ. Behav. 2018, 45, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, K.; Olds, T.S.; Hill, A. The Multimedia Activity Recall for Children and Adolescents (MARCA): Development and evaluation. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillon, A.; Pereira, B.; Vanhelst, J.; Baran, J.; Masurier, J.; Guirado, T.; Boirie, Y.; Duclos, M.; Julian, V.; Thivel, D. Development of the Children and Adolescents Physical Activity and Sedentary Questionnaire (CAPAS-Q): Psychometric Validity and Clinical Interpretation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.V. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Lakshman, R.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Barriers and facilitators to young children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative literature. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 987–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, L.D.; Tebar, W.R.; Tebar, F.; JM, D.E.S.; Romanzini, M.; Fernandes, R.A.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Association between sedentary behavior, obesity and hypertension in public school teachers. Ind. Health 2020, 58, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruedl, G.; Niedermeier, M.; Wimmer, L.; Ploner, V.; Pocecco, E.; Cocca, A.; Greier, K. Impact of Parental Education and Physical Activity on the Long-Term Development of the Physical Fitness of Primary School Children: An Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D. Central mechanisms of obesity and related metabolic diseases. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2013, 14, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Chaput, J.P.; Saunders, T.J.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Okely, A.D.; Connor Gorber, S.; et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: An update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S240–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, M.E.; Fragala-Pinkham, M.A.; Forman, J.L.; Trost, S.G. Measuring reliability and validity of the ActiGraph GT3X accelerometer for children with cerebral palsy: A feasibility study. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 7, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyau, M.R.; Adolph, A.L.; Vohra, F.A.; Butte, N.F. Validation and calibration of physical activity monitors in children. Obes. Res. 2002, 10, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treuth, M.S.; Sherwood, N.E.; Baranowski, T.; Butte, N.F.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; McClanahan, B.; Gao, S.; Rochon, J.; Zhou, A.; Robinson, T.N.; et al. Physical activity self-report and accelerometry measures from the Girls health Enrichment Multi-site Studies. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, S43–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cliff, D.P.; Reilly, J.J.; Okely, A.D. Methodological considerations in using accelerometers to assess habitual physical activity in children aged 0–5 years. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, L.A.; Glynn, N.W.; King, A.C.; Guralnik, J.M.; Aiken, E.K.; Miller, G.; Haskell, W.L. Use of accelerometry to measure physical activity in older adults at risk for mobility disability. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2008, 16, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Moraes, A.C.F.; Nascimento-Ferreira, M.V.; Forjaz, C.L.D.M.; Aristizabal, J.C.; Azzaretti, L.; Nascimento Junior, W.V.; Miguel-Berges, M.L.; Skapino, E.; Delgado, C.; Moreno, L.A.; et al. Reliability and validity of a sedentary behavior questionnaire for South American pediatric population: SAYCARE study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Gil, E.M.; Mouratidou, T.; Cardon, G.; Androutsos, O.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Góźdź, M.; Usheva, N.; Birnbaum, J.; Manios, Y.; Moreno, L.A. Reliability of primary caregivers reports on lifestyle behaviours of European pre-school children: The ToyBox-study. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15 (Suppl. S3), 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-López, J.P.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Verloigne, M.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Gottrand, F.; Molnar, D.; Widhalm, K.; Zaccaria, M.; et al. Reliability and validity of a screen time-based sedentary behaviour questionnaire for adolescents: The HELENA study. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study ID | Location | Journal Published | n | Age (Years) | Females (%) | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Janz et al., 2005 [18] | Netherlands | Res Q Exerc Sport | 204 | 4–7 | 55.3 | Cross-sectional |

| Ridley et al., 2006 [21] | Australia | Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act | 1429 | 9–15 | 51.1 | Cross-sectional |

| Jago et al., 2009 [19] | US | Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act | 714 | 11.3 | 49.1 | Cross-sectional |

| Dwyer et al., 2011 [17] | Australia | Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act | 105 | 4–5.9 | 48.0 | Cross-sectional |

| Vaughn et al., 2013 [16] | US | Med Sci Sports Exerc | 324 | 2–5 | NA | Cross-sectional |

| Norman et al., 2018 [20] | Stockholm County | Health Educ Behav | 229 | 5.8–7.1 | 51.5 | Cluster-randomized trial |

| Fillon et al., 2022 [22] | France | Int J Environ Res Public Health | 103 | 8–18 | 52.5 | Cross-sectional |

| Study ID | Sample Size | Length of Reliability Test | Subjective Tool | Number of Questions in the Questionnaire | Internal Consistency (Test) | Test Results | Test-Retest Reliability | Reliability Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Janz et al., 2005 [18] | 72 | NR | (NAPQ) Questionnaire | 1 | NA | NA | (1) Coefficient kappas (κ) (2) Spearman correlation (rho) | (1) κ = 0.39 (2) rho = 0.30 to 0.66 |

| Ridley et al., 2006 [21] | 32 | two times in the same day | (MARCA) Questionnaire | 1 | NA | NA | (1) ICC | (1) ICC = 0.88 to 0.94 |

| Jago et al., 2009 [19] | 555 | NR | (PASE) Questionnaire | 24 | (1) Cronbach’s alpha (α) | (1) (α) = 0.84 | (1) Cronbach’s alpha/ Person-separation reliability | (1) full scale 0.75–0.90 |

| Dwyer et al., 2011 [17] | 103 | two weeks apart | (Pre-PAQ) Questionnaire | 7 | NA | NA | (1) ICC (2) Coefficient kappas (κ) | (1) ranged from 0.31–1.00 (ICC (2, 1)) (2) κ = 0.60–0.97 |

| Vaughn et al., 2013 [16] | 303 | NR | NR | 7 | (1) Cronbach’s alpha (α) | (1) (α) = 0.54–0.88 | NA | NA |

| Norman et al., 2018 [20] | 229 | NR | (EPAQ) Questionnaire | 2 | (1) Cronbach’s alpha (α) | (1) α = 0.87 | (1) Cronbach’s alpha (α) | Factor 1 (α = 0.81) Factors 2 (α = 0.79) Factors 3 (α = 0.77) |

| Fillon et al., 2022 [22] | 103 | 7 days | (CAPAS-Q) Questionnaire | 31 | (1) Cronbach’s alpha (α) | (1) α = 0.71 and 0.68 | (1) Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient | (1) 0.193 ep = 0.076 |

| Study ID | Sample Size | Length of Validity Test | Objective Assessment | Units of Measurement | Validity Estimate | Validity Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Janz et al., 2005 [18] | 204 | 4 days | accelerometer | min/day | Spearman correlation | 0.16 |

| Ridley et al., 2006 [21] | 66 | 1 day | accelerometer | min/day | Spearman correlation | 0.36 to 0.45 |

| Jago et al., 2009 [19] | 83 | 5 days | accelerometer | min/day | ICC | (r = 0.17–0.33) |

| Dwyer et al., 2011 [17] | 67 | 4 days | accelerometer | min/day | Pearson correlation | 0.19–0.28 |

| Vaughn et al., 2013 [16] | 303 | 4 days | accelerometer | min/day | Pearson correlation | −0.1 to 0.08 |

| Norman et al., 2018 [20] | NR | 7 days | accelerometer | min/day | Pearson correlation | NA |

| Fillon et al., 2022 [22] | 103 | 7 days | accelerometer | min/day | Pearson correlation and Spearman correlation | NR |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, G.A.; Marcelino, A.C.; Tristão Parra, M.; Nascimento-Ferreira, M.V.; De Moraes, A.C.F. Validity and Reliability of Questionnaires That Assess Barriers and Facilitators of Sedentary Behavior in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416834

Oliveira GA, Marcelino AC, Tristão Parra M, Nascimento-Ferreira MV, De Moraes ACF. Validity and Reliability of Questionnaires That Assess Barriers and Facilitators of Sedentary Behavior in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416834

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Guilherme Augusto, Andressa Costa Marcelino, Maíra Tristão Parra, Marcus Vinicius Nascimento-Ferreira, and Augusto César Ferreira De Moraes. 2022. "Validity and Reliability of Questionnaires That Assess Barriers and Facilitators of Sedentary Behavior in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416834

APA StyleOliveira, G. A., Marcelino, A. C., Tristão Parra, M., Nascimento-Ferreira, M. V., & De Moraes, A. C. F. (2022). Validity and Reliability of Questionnaires That Assess Barriers and Facilitators of Sedentary Behavior in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416834