Utilisation of Digital Applications for Personal Recovery Amongst Youth with Mental Health Concerns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

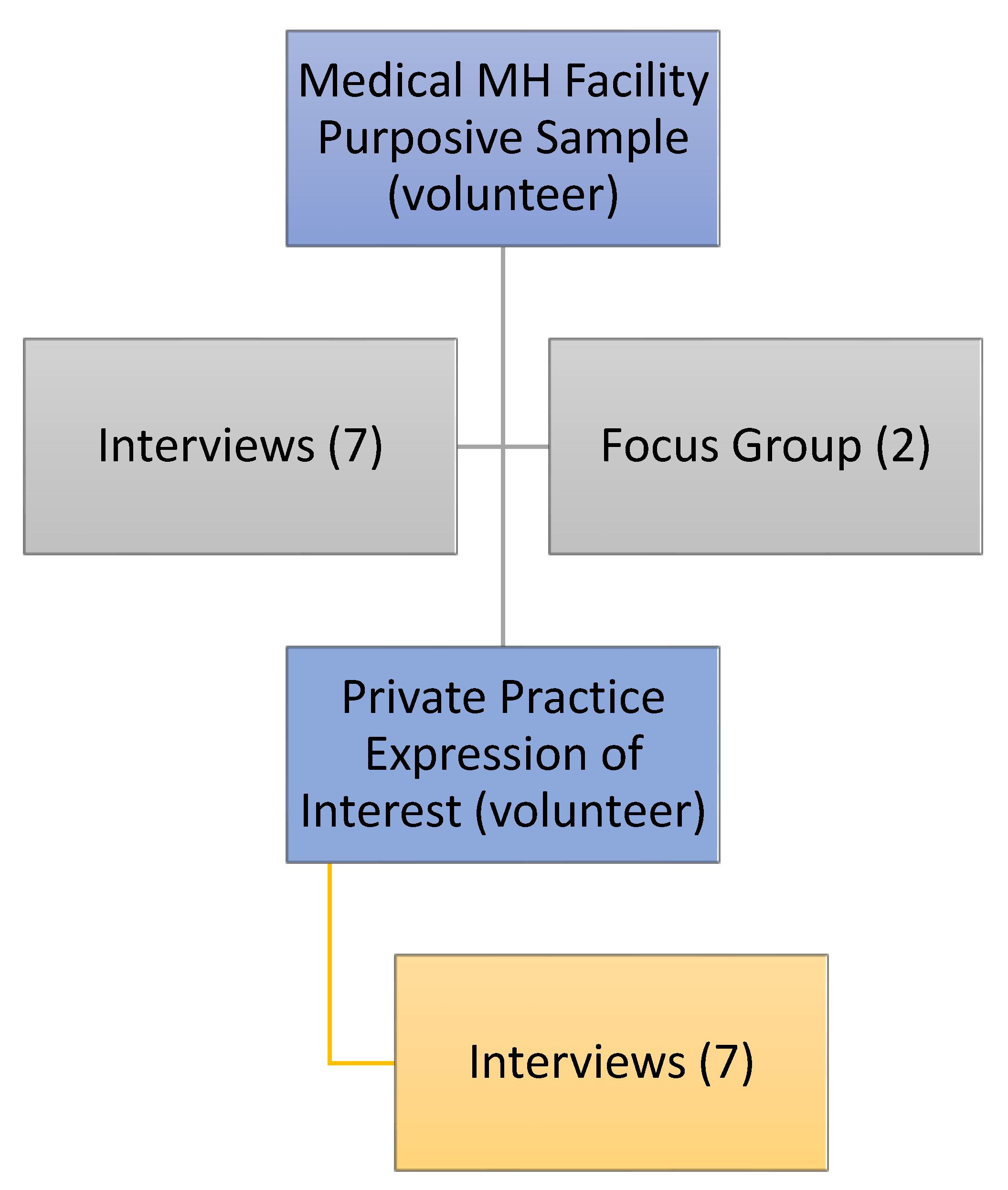

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Inductive Analysis

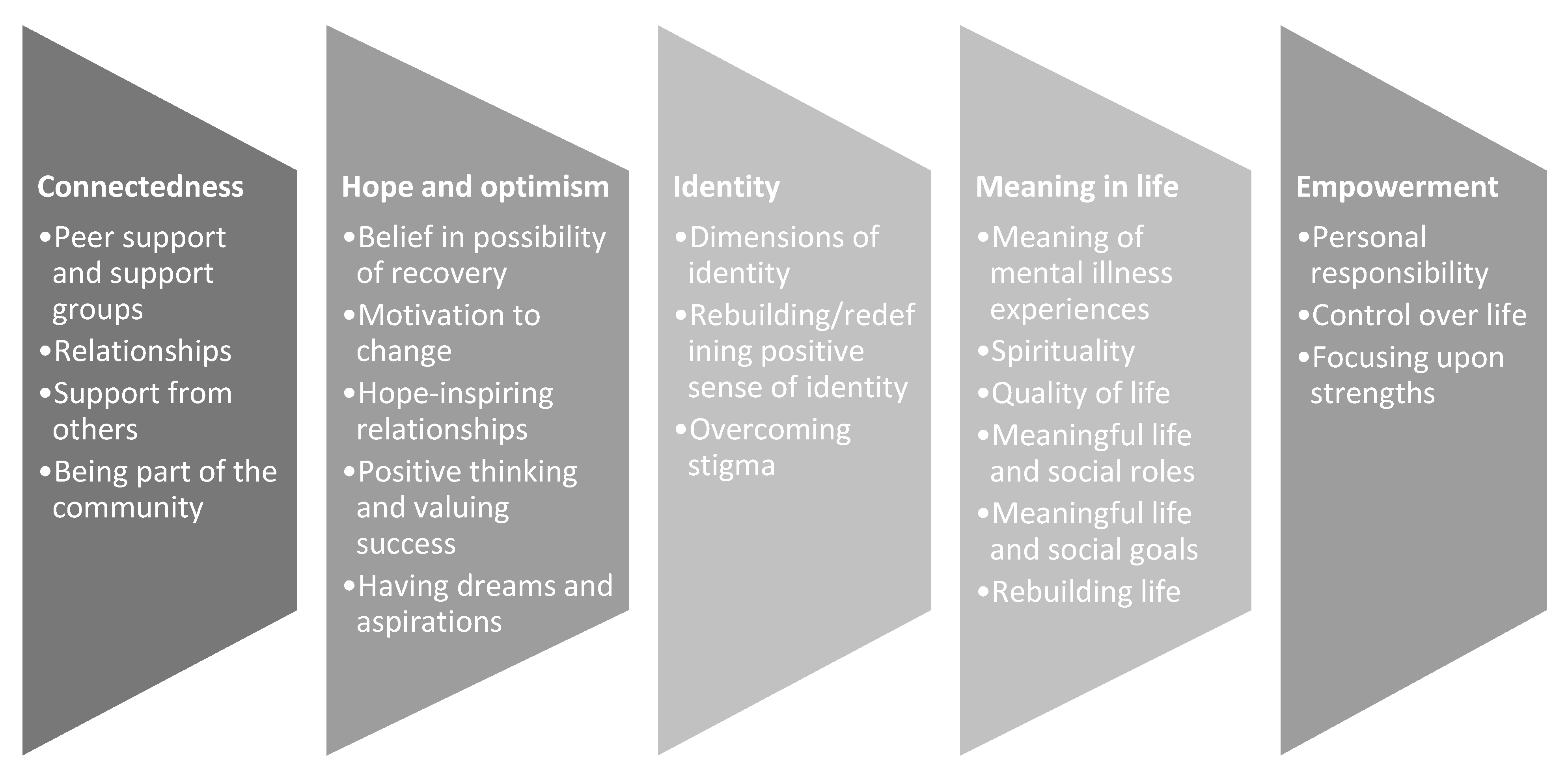

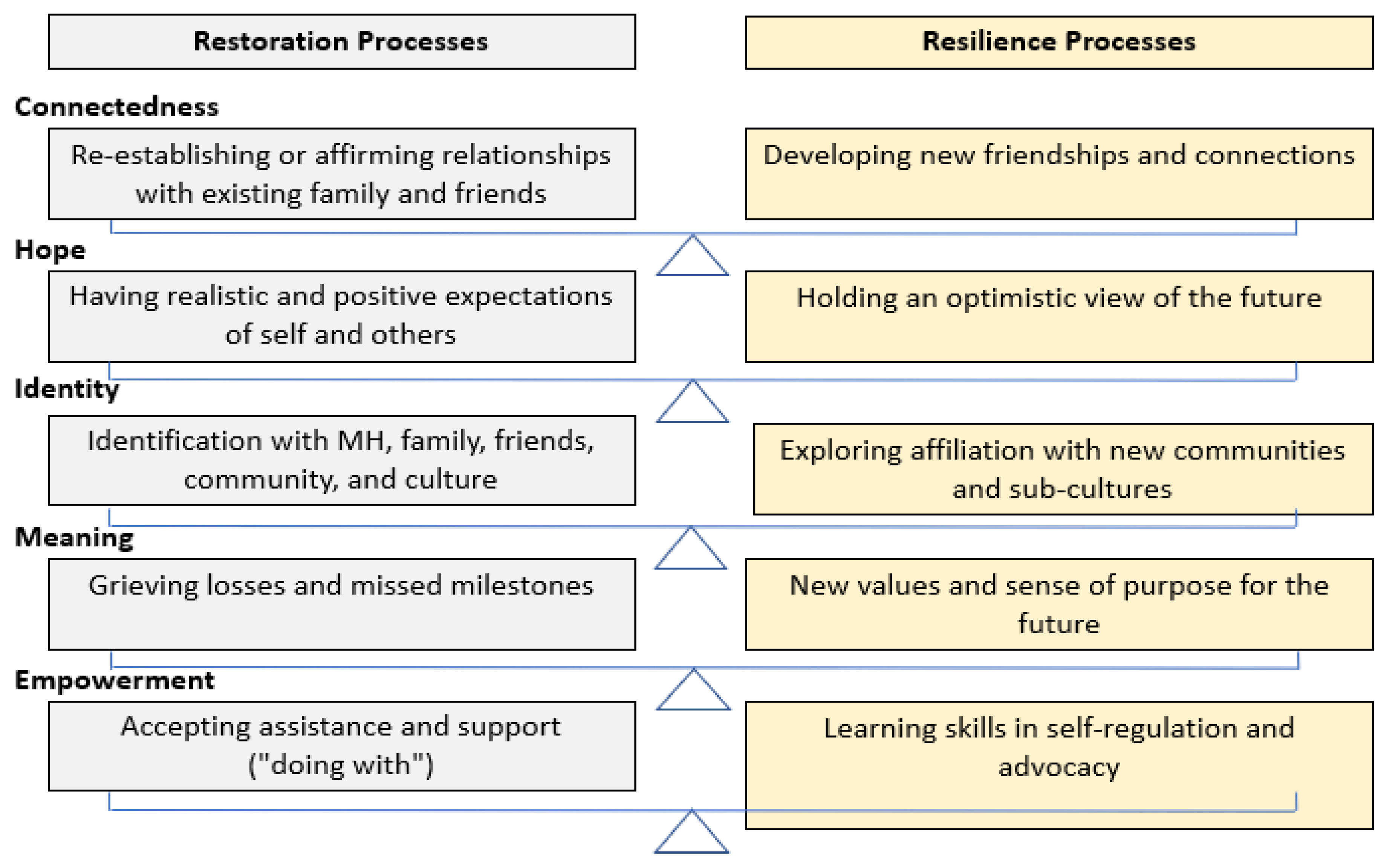

3.3. Deductive Analysis

3.3.1. Connectedness

3.3.2. Hope

3.3.3. Identity

3.3.4. Meaning

3.3.5. Empowerment

3.3.6. Key Elements of Digital Applications Supporting Youth Recovery

3.4. Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question Content | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 | What Apps and internet tools are you using to help you? When are you using them? Who are you using them with? How do they help you? |

| Question 2 | Describe yourself using three words or how would someone who loves you describe you using three words or choose three strength cards that represent you from those provided. |

| Question 3 | (Choice 1, 2, 3) I am/chose this word/card because? |

| Question 4 | What does a good day look like for you? (or “If you were to wake up and have a great day, what would we see you doing?) Where are you? Who is around you? What are you doing that makes you feel better about yourself? |

| Question 5 | What may have happened or changed to make it a good day? |

| Question 6 | If there was a website, app, or online program to support you and your family with getting better, what information would it contain? What would it look like? How would you use it? |

Appendix B

| Question Content | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 | How does this video correspond to your experience of MH? |

| Question 2 | Do you find the language appropriate? If not, what would you change? |

| Question 3 | Please provide feedback on the following: Duration, appearance, colour, use of stills versus talking heads |

References

- Burns, J.M.; Birrell, E.; Bismark, M.; Pirkis, J.; Davenport, T.; Hickie, I.; Weinberg, M.; Ellis, L. The Role of Technology in Australian Youth Mental Health Reform. Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, D. ‘Recovery’: Does It Fit for Adolescent Mental Health? J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2014, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C. Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Progress and Future Directions. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGorry, P.D.; Purcell, R.; Hickie, I.B.; Jorm, A.F. Investing in Youth Mental Health Is a Best Buy. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, S5–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Coughlan, B. A Theory of Youth Mental Health Recovery from a Parental Perspective. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 24, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, S.J.; Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J. Burden of Psychiatric Disorder in Young Adulthood and Life Outcomes at Age 30. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C.; Chanen, A.; Hodges, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Killackey, E. Designing and Scaling up Integrated Youth Mental Health Care. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, N.; Beames, J.R.; Kos, A.; Reily, N.; Connell, C.; Hall, S.; Yip, D.; Hudson, J.; O’Dea, B.; Di Nicola, K.; et al. Psychological Distress in Young People in Australia Fifth Biennial Youth Mental Health Report: 2012–2020; Mission Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Grist, R.; Croker, A.; Denne, M.; Stallard, P. Technology Delivered Interventions for Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Children’s Rights Report 2016; Australian Human Rights Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2016.

- Rickwood, D.J.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.J.; Ciarrochi, J. Young People’s Help-Seeking for Mental Health Problems. Aust. e-J. Adv. Ment. Health 2005, 4, 218–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Mental Health Help-Seeking in Young People: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernáez, A.; DiGiacomo, S.M.; Carceller-Maicas, N.; Correa-Urquiza, M.; Martorell-Poveda, M.A. Non-Professional-Help-Seeking among Young People with Depression: A Qualitative Study. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Schauman, O.; Graham, T.; Maggioni, F.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Morgan, C.; Rüsch, N.; Brown, J.S.L.; Thornicroft, G. What Is the Impact of Mental Health-Related Stigma on Help-Seeking? A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, S.; Mantler, E.; Szeto, A. Mental Illness-Related Stigma in Healthcare: Barriers to Access and Care and Evidence-Based Solutions. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2017, 30, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebowitz, M.S.; Appelbaum, P.S. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology Biomedical Explanations of Psychopathology and Their Implications for Attitudes and Beliefs about Mental Disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 15, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. The Social Self: On Being the Same and Different at the Same Time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W. How Clinical Diagnosis Might Exacerbate the Stigma of Mental Illness. Soc. Work 2007, 52, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from Mental Illness: The Guiding Vision of the Mental Health Service System in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Conceptual Framework for Personal Recovery in Mental Health: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, M.W.; Psych, B.; Remington, G. Personal Recovery in Serious Mental Illness: Making Sense of the Concept Recovery in Serious Mental Illness. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2017, 46, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson, R.; Pesola, F.; Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. The Relationship between Clinical and Recovery Dimensions of Outcome in Mental Health. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 175, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health Information Strategy Standing Committee. Measuring Recovery in Australian Specialised Mental Health Services: A Status Report; Australian Mental Health Minister’s Advisory Council (AHMAC): Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Slade, M.; Oades, L.G.; Jarden, A. Recovery and Mental Health. In Wellbeing, Recovery and Mental Health; Slade, M., Oades, L., Jarden, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; ISBN 1107543053. [Google Scholar]

- Poole Heller, D. The Power of Attachment: How to Create Deep and Lasting Intimate Relationships; Sounds True: Boulder, CO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M. Recovery Research: The Empirical Evidence from England. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneidtinger, C.; Haslinger-Baumann, E. The Lived Experience of Adolescent Users of Mental Health Services in Vienna, Austria: A Qualitative Study of Personal Recovery. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 32, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, J.; Henderson, C. Recovery for Young People: Recovery Orientation in Youth Mental Health and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS): Discussion Paper; Mental Health Coordinating Council: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Naughton, J.N.L.; Maybery, D.; Sutton, K. Review of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Recovery Literature: Concordance and Contention. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2018, 5, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, S.; Thielking, M.; Lough, R. A New Paradigm of Youth Recovery: Implications for Youth Mental Health Service Provision. Aust. J. Psychol. 2018, 70, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, B.J. Recovery and Resilience in Children’s Mental Health: Views from the Field. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2007, 31, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonds, L.M.; Pons, R.A.; Stone, N.J.; Warren, F.; John, M. Adolescents with Anxiety and Depression: Is Social Recovery Relevant? Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2014, 21, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, H.; Lapsley, H. Journeys of Despair, Journeys of Hope: Young Adults Talk about Severe Mental Distress; Mental Health Services and Recovery: Wellington, New Zealand, 2006.

- Dallinger, V.C.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; du Plessis, C.; Pillai-Sasidharan, A.; Ayres, A.; Waters, L.; Groom, Y.; Sweeney, K.; Rees, B.; Brown, S.; et al. Conceptualisation of Personal Recovery for Youth: Multi-Systemic Perspectives. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 2022. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood, D.J.; Mazzer, K.R.; Telford, N.R. Social Influences on Seeking Help from Mental Health Services, in-Person and Online, during Adolescence and Young Adulthood. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, G.M.; Donovan, C.L.; March, S.; Forbes, Y. Logging into Therapy: Adolescent Perceptions of Online Therapies for Mental Health Problems. Internet Interv. 2019, 15, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, C.; Chambers, D.; Cowan, B.; Coyle, D. Young People Seeking Help Online for Mental Health: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e13524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M.; Davenport, T.A.; Durkin, L.A.; Luscombe, G.M.; Hickie, I.B. The Internet as a Setting for Mental Health Service Utilisation by Young People. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, S22–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Household Use of Information Technology. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/8146.0 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Lawrence, D.; Johnson, S.; Hafekost, J.; Boterhoven De Haan, K.; Sawyer, M.; Ainley, J.; Zubrick, S.R. The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Rauschenberg, C.; Schick, A.; Goetzl, C.; Roehr, S.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Koppe, G.; Durstewitz, D.; Krumm, S.; Reininghaus, U. Social Isolation, Mental Health, and Use of Digital Interventions in Youth during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationally Representative Survey. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, A.; Grohol, J.M. Current and Future Trends in Internet-Supported Mental Health Interventions. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2011, 29, 155–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallinger, V.C.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Burton, L.J.; du Plessis, C.; Pillai-Sasidharan, A.; Ayres, A. Internet Interventions Supporting Recovery in Youth: A Systematic Literature Review. Digit. Health 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickter, B.; Bunge, E.L.; Brown, L.M.; Leykin, Y.; Soares, E.E.; Van Voorhees, B.; Marko-Holguin, M.; Gladstone, T.R.G. Impact of an Online Depression Prevention Intervention on Suicide Risk Factors for Adolescents and Young Adults. mHealth 2019, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicavasagar, V.; Horswood, D.; Burckhardt, R.; Lum, A.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Parker, G. Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Web-Based Positive Psychology Program for Youth Mental Health: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Poyser, C.T.; Mackinnon, A.J.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial of the E-Couch Anxiety and Worry Program in Schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 196, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Voorhees, B.W.; Vanderplough-Booth, K.; Fogel, J.; Gladstone, T.; Bell, C.; Stuart, S.; Gollan, J.; Bradford, N.; Domanico, R.; Fagan, B.; et al. Integrative Internet-Based Depression Prevention for Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Primary Care for Vulnerability and Protective Factors. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Lillevoll, K.R.; Vangberg, H.C.B.; Griffiths, K.M.; Waterloo, K.; Eisemann, M.R. Uptake and Adherence of a Self-Directed Internet-Based Mental Health Intervention with Tailored e-Mail Reminders in Senior High Schools in Norway. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.H.; Donovan, C.L.; March, S.; Gamble, A.; Anderson, R.E.; Prosser, S.; Kenardy, J. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Online versus Clinic-Based CBT for Adolescent Anxiety. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Hetrick, S.; Cox, G.; Bendall, S.; Yung, A.; Yuen, H.P.; Templer, K.; Pirkis, J. The Development of a Randomised Controlled Trial Testing the Effects of an Online Intervention among School Students at Risk of Suicide. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, S.E.; Yuen, H.P.; Bailey, E.; Cox, G.R.; Templer, K.; Rice, S.M.; Bendall, S.; Robinson, J. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Young People with Suicide-Related Behaviour (Reframe-IT): A Randomised Controlled Trial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2017, 20, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannink, R.; Broeren, S.; Joosten-van Zwanenburg, E.; van As, E.; van de Looij-Jansen, P.; Raat, H. Effectiveness of a Web-Based Tailored Intervention (E-Health4Uth) and Consultation to Promote Adolescents’ Health: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kearney, R.; Gibson, M.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K.M. Effects of a Cognitive-behavioural Internet Program on Depression, Vulnerability to Depression and Stigma in Adolescent Males: A School-based Controlled Trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2006, 35, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.; Hickie, I.B. Using E-Health Applications to Deliver New Mental Health Services. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, S53–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallard, P.; Udwin, O.; Goddard, M.; Hibbert, S. The Availability of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy within Specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS): A National Survey. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2007, 35, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Youth. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R.; Wutich, A.; Ryan, G.W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1483347117. [Google Scholar]

- Ritterband, L.M.; Thorndike, F.P.; Cox, D.J.; Kovatchev, B.P.; Gonder-Frederick, L.A. A Behavior Change Model for Internet Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 38, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Utley, A.; Garza, Y. The Therapeutic Use of Journaling with Adolescents. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2011, 6, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Dogra, N.; Whiteman, N.; Hughes, J.; Eruyar, S.; Reilly, P. Is Social Media Bad for Mental Health and Wellbeing? Exploring the Perspectives of Adolescents. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.P.; Heath, N.L.; Michal, N.J.; Duggan, J.M. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury, Youth, and the Internet: What Mental Health Professionals Need to Know. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2012, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, I.H.; Thompson, A.; Valentine, L.; Adams, S.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Nicholas, J. Ownership, Use of, and Interest in Digital Mental Health Technologies among Clinicians and Young People across a Spectrum of Clinical Care Needs: Cross-Sectional Survey. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e30716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S.; Gleeson, J.; Davey, C.; Hetrick, S.; Parker, A.; Lederman, R.; Wadley, G.; Murray, G.; Herrman, H.; Chambers, R.; et al. Moderated Online Social Therapy for Depression Relapse Prevention in Young People: Pilot Study of a ‘next Generation’ Online Intervention. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 12, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M.; Shaw, R.; Flowers, P. Multiperspectival Designs and Processes in Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2018, 16, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Age | Residence | Diagnosis | Days in Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 15 | Metropolitan | Social phobias | 538 |

| Male | 15 | Metropolitan | Other reactions to severe stress | 625 |

| Non-binary | 15 | Metropolitan | Dissociative motor disorder | 128 |

| Female | 16 | Regional | OCD | 243 |

| Non-binary | 16 | Metropolitan | PTSD | 173 |

| Female | 16 | Metropolitan | Eating disorder | 244 |

| Trans female | 16 | Remote | Depression | 121 |

| Female | 16 | Metropolitan | Conversion disorder | 106 |

| Female | 16 | Rural | GAD, eating disorder | 132 |

| Male | 16 | Metropolitan | ARFID | 237 |

| Female | 16 | Metropolitan | ADHD, GAD | 316 |

| Female | 17 | Metropolitan | OCD | 167 |

| Female | 17 | Rural | ASD, ADHD, PTSD | 238 |

| Female * | 18 | Metropolitan | Trauma and stressor-related diorders | 98 |

| Female | 18 | Rural | GAD | 267 |

| Male * | 21 | Metropolitan | Depression, psychosis | 0 ** |

| Diagnosis/MH Symptoms | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | 5 |

| Stress related | 4 |

| Eating disorder | 3 |

| OCD | 2 |

| Depression | 2 |

| ADHD | 2 |

| Somatic | 2 |

| ASD | 1 |

| Psychosis | 1 |

| Tally | Digital Resource | Purpose of Use | CHIME Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Video streaming (e.g., YouTube) | Distraction | C |

| 3 | Social media (e.g., Tik Tok, Instagram, Snapchat) | Connection/distraction | C, I |

| 3 | Mindfulness and meditation (e.g., Calm) | Mood regulation | E |

| 5 | Music streaming (e.g., Spotify, Apple Music) | Mood regulation/connection | C, I, E |

| 2 | Story reading applications (Abide, Audible) | Mood regulation/distraction | C, M |

| 3 | MH websites (Beyond Blue; Kids Helpline, Lifeline) | Meaning-making/connection | C, M |

| 4 | Journalling applications | Reflection | H, I, E |

| 5 | Goal setting/planning (e.g., Forest, Sober, Beyond Now) | Goal setting/planning/self-regulation | M, E |

| 1 | Gaming applications | Distraction/connection | C |

| Tally | CHIME Processes |

|---|---|

| 15 | Connectedness |

| 4 | Hope |

| 8 | Identity |

| 10 | Meaning |

| 17 | Empowerment |

| Generic Category | Sub-categories | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| Restorative Processes | Communicating difficult experiences | I guess it would be easier to just say download this App and tell my parents to like have a look at this. |

| Brief communications | Just being able to talk to family and friends and having that interaction. | |

| Communicating in times of need | It was nice just to feel like someone was listening to me when I was messaging the support worker like they connected me to someone. | |

| Reconnecting with others through reminiscing | …and like even just last night, we were sitting with the chairs, and we were playing through all of our favourite songs… | |

| Scheduling | …and then I probably like set up what I think tomorrow is going to be like … and just how I can like do it better I guess. | |

| Resilience Processes | Connecting to virtual communities | You know, somewhere where people who have MH can log into and become part of a community. |

| Online gaming communities | I used to like play games, sometimes with my friends. Just like mini-games I play with my partner when I can’t see them. | |

| Chat groups | Somewhere to just talk about other stuff that you like, not just your issues. | |

| Online contact with health & welfare professionals | Because I didn’t feel comfortable talking on the phone because I didn’t know who it was and I’m not really comfortable talking on the phone anyway. But it was nice just to feel like someone was listening to me when I was messaging the support worker like they connected me to someone. They gave me resources to… |

| Generic Category | Sub-categories | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| Restorative Processes | Information about MH prognosis | I’ve been on like websites to learn more about, like my diagnosis and diagnoses and stuff. |

| Sharing progress and celebrating gain | … it’s like how long you like stop doing these negative like bad coping mechanisms. | |

| Being Heard | You can ring somebody, and it doesn’t matter what time of day it is, somebody is there to chat to or get back to you. | |

| Resilience Processes | Stories offer encouragement and hope | I like reading about like other people who have recovered or are learning to get through it as well. Who have experienced similar things and I guess just… strategies, and kind of like things to do because when you are having a bad day, you can’t really see why you are doing it, like why you are trying. So maybe just something to remind you that you do want this. |

| Support for striving | … like you can take notes and put your thoughts in it. And if you like, relapse or if you are just having a rough day, it gives you things like contact info and like just little quotes and it reminds you of why you’re doing it. It’s cool. | |

| Delight and distraction | I sort of am the DJ of the household and like during cooking groups and stuff, I put the music on. | |

| Sharing delight | I like making people laugh. Yeah, with jokes or little comments. | |

| Hope through belonging | Like your special interests and stuff like that. So, some way to share and to help other people with their stuff. |

| Generic Category | Sub-categories | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| Restorative Processes | Reconnecting with self through reminiscing | …and like even just last night, we were sitting with the chairs, and we were playing through all of our favourite songs… |

| Affirming and celebrating identity | It’s a faith-based one so some of it is like a … Biblical like scriptures and they play stories from the Bible. | |

| Resilience Processes | Information about prevalence of MH concerns | I kind of like statistics like you know, like how many people have this. Like this type of therapy is best. |

| Stories of positive identities related to MH | Maybe some information from people who have done it themselves. | |

| Building a new sense of self | Somewhere to just talk about other stuff that you like, not just your issues if that makes sense… like your special interests and stuff like that. |

| Generic Category | Sub-categories | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| Restorative Processes | Vicarious grieving: Redefining past opportunities | Maybe some information from, I guess maybe people who have done it themselves. |

| Reflecting on the past | …and if I’m feeling down or sad, I’ll play music that is familiar to me so that I can, like, feel something familiar or sad. This is familiar to me because I feel that pretty much all the time. | |

| Resilience Processes | Discovering growth from adversity | Just like some stories that people have gone through and how they, like did it but also how they’re saying it’s not going to be this easy or it’s not easy but keep trying and stuff. |

| Understanding MH | They gave me resources to, perhaps refer to for things that I was worried about. Or for further reference or whatever. | |

| Making meaning through Expression | Maybe like a way to keep a journal. Because I feel like that’s very helpful to kind of see patterns. |

| Generic Category | Sub-categories | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| Restorative Processes | Building Acceptance | It’s going on like to kind of give you like example or something like in real life. |

| Sharing progress and celebrating gain | …maybe like a way to keep a journal. Because I feel like that’s very helpful to kind of see patterns. You know, and what’s happening… | |

| Resilience Processes | Shifting Attention | I was listening to music to try and just get me to go like get more creative and stuff. And I use it to focus on my schoolwork and I use it to calm down if I’m having panic attacks and stuff. |

| Using the Voice of Experience | …where you can talk to people who go through similar things and sort of see what helps them and what helps you and sort of try to help each other. | |

| Shopping for Success | …if I’m having urges to engage in negative behaviours, I try to look at the good coping strategies and replace them. | |

| Having a Voice | I think I personally know that I’ve gone through a lot and the fact that I’m still here and that I could give good and helpful advice to people. | |

| Normative Regulation | I feel like a lot of other young people use Spotify or like Apple music just to calm down like their emotions when they listen to music. |

| Theme | Descriptions | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Bright colours and simple layout with large font | Yeah, brightly coloured. Vibrant, just like a happy feeling. |

| Assessment | Personalised goal setting and tracking | So different customisable features to make it so sort of more personalised. |

| Behavioural prescriptions | Easy navigation with help functions and feedback channel | Sometimes when I find an App it looks complicated, just don’t end up using it because it’s too hard. |

| Reducing burdens | A free resource that comprises short interventions in a safe environment supporting confidentiality | I feel like maybe it would be nice to see some information from like psychs and stuff. I do like to see how other people deal with it. |

| Content | Educational interventions including lived experience and forums for connection supporting youth, caregivers, and professionals | I think like an online portal when there’s a chat 24/7 would be good… probably people that have been there and done that and can offer advice… |

| Delivery | Presenting information with talking heads, animations, and text to support all preferences for learning | I feel like a video would be cool, too. I mean, everyone learns, or everyone takes in information differently, so I feel like there should be variety to make sure everyone can use it and benefit from that information. |

| Message | Co-developed content that is catchy and relevant to the present and younger population | But there’s opportunities at places like <facility> where you can all grow together and learn together. |

| Participation | Include inspirational and fun measures of recovery through games and interactive quizzes and trackers | I feel like I would use it when I kind of wanted to do something to help myself but couldn’t really think what to do. So that whole thing about activities or ideas, or processes. Make yourself feel better, happier. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dallinger, V.C.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; du Plessis, C.; Pillai-Sasidharan, A.; Ayres, A.; Waters, L.; Groom, Y.; Alston, O.; Anderson, L.; Burton, L. Utilisation of Digital Applications for Personal Recovery Amongst Youth with Mental Health Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416818

Dallinger VC, Krishnamoorthy G, du Plessis C, Pillai-Sasidharan A, Ayres A, Waters L, Groom Y, Alston O, Anderson L, Burton L. Utilisation of Digital Applications for Personal Recovery Amongst Youth with Mental Health Concerns. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416818

Chicago/Turabian StyleDallinger, Vicki C., Govind Krishnamoorthy, Carol du Plessis, Arun Pillai-Sasidharan, Alice Ayres, Lillian Waters, Yasmin Groom, Olivia Alston, Linda Anderson, and Lorelle Burton. 2022. "Utilisation of Digital Applications for Personal Recovery Amongst Youth with Mental Health Concerns" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416818

APA StyleDallinger, V. C., Krishnamoorthy, G., du Plessis, C., Pillai-Sasidharan, A., Ayres, A., Waters, L., Groom, Y., Alston, O., Anderson, L., & Burton, L. (2022). Utilisation of Digital Applications for Personal Recovery Amongst Youth with Mental Health Concerns. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416818