Turning to ‘Trusted Others’: A Narrative Review of Providing Social Support to First Responders

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Emotional support refers to providing trust, empathy, love, and care for the person seeking help.

- Instrumental support offers tangible services or practical help.

- Appraisal support includes providing affirmation or information relevant for self-evaluation.

- Informational support provides knowledge.

- How do trusted others currently provide social support to their first responders?

- How are trusted others prepared to support their first responders (their readiness, coping strategies, and available resources)?

- How can trusted others be best prepared to provide social support?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.3. Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Themes and Interpretation

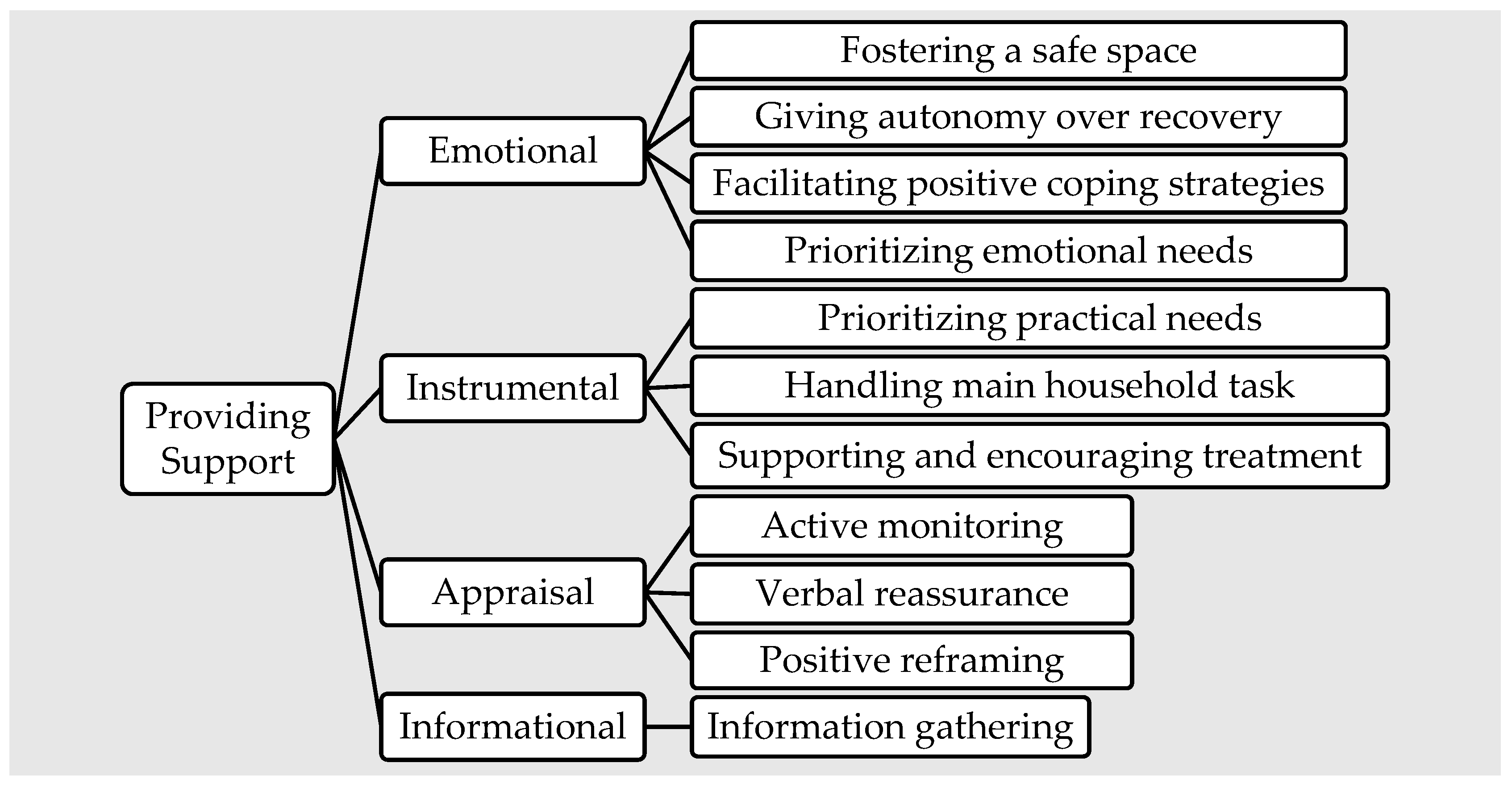

3.2. Theme 1-Providing Support

3.2.1. Emotional Support

“So, actually listening to what the issue is, and then being able to draw out what the actual trigger is that’s causing the stress.”[42] (p. 159)

3.2.2. Instrumental Support

“It was a war; we were on the home front holding it down.”[51] (p. 910)

3.2.3. Appraisal Support

“Jane reported that she had to learn to be different. To read his moods and know when he has had a bad day and try to encourage him.”[52] (p. 48)

3.2.4. Informational Support

“Most of what we know [about PTSD] comes from news broadcasts, the movies, or the Internet.”[40] (p. 746)

3.3. Theme 2-Finding Support

3.3.1. Formal Coping and Use of Resources

3.3.2. Informal Coping and Use of Resources

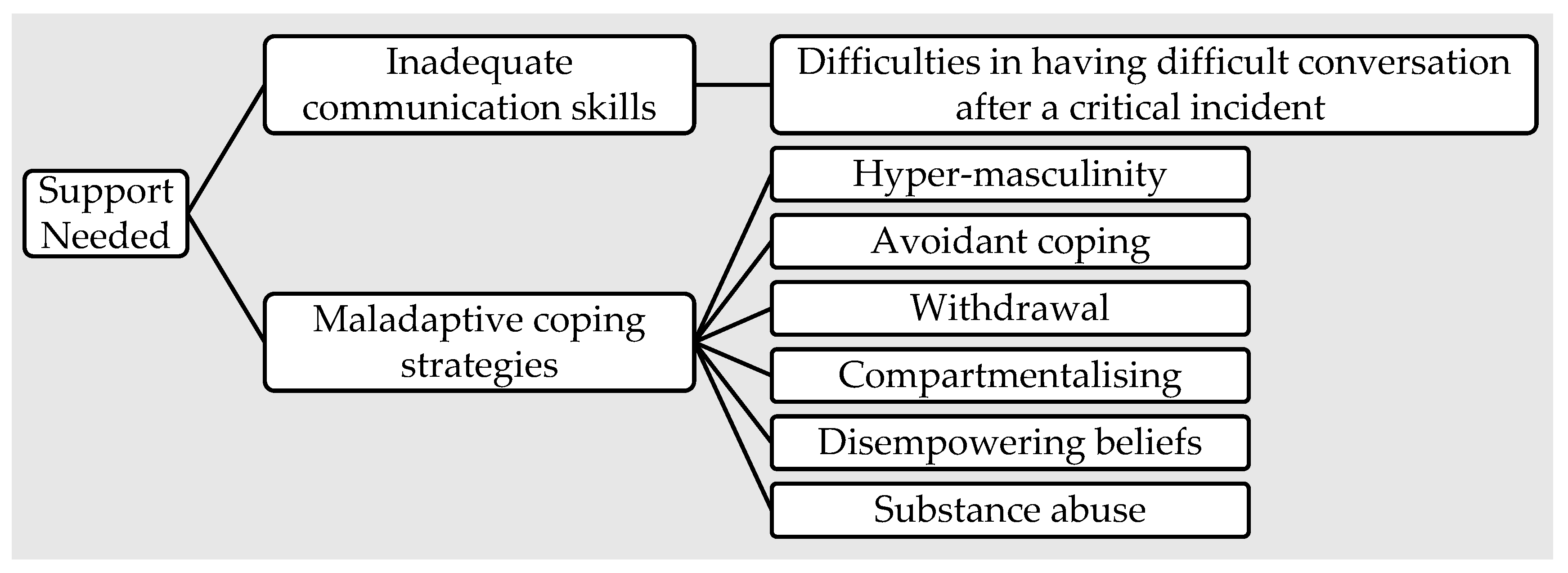

3.4. Theme 3-Support Needed

“I lived my life walking on eggshells and how I made the kids walk on eggshells.”[37] (p. 651)

Recommendations

4. Discussion

- Factors that foster the development of a comprehensive and culturally competent understanding of all facets of trusted other social support related to specific needs and experiences.

- Optimal research design and evaluation of interventions, programs, and training for trusted others’.

- Strategies to co-develop informal and formal support systems for trusted others and their first responder.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L. The relation of perceived and received social support to mental health among first responders: A meta-analytic review. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, D.M.; Fullerton, C.; Ursano, R.J. First responders: Mental health consequences of natural and human-made disasters for public health and public safety workers. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2007, 28, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woody, R. The police culture: Research implications for psychological services. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005, 36, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.C.; Holmes, L.; Burkle, F.M. The physical and mental health challenges experienced by 9/11 first responders and recovery workers: A review of the literature. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2019, 34, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angleman, A.J.; Van Hasselt, V.B.; Schuhmann, B.B. Relationship between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Firefighters. Behav Modif. 2022, 46, 321–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.S.; Litzenberger, R.; Plecas, D. Physical evidence of police officer stress. Polic. Int. J. 2002, 25, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, P.T.; Evces, M.; Weiss, D.S. Treating posttraumatic stress disorder in first responders: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM): Group Crisis Intervention, 4th ed.; Chevron: Ellicott City, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, J. Military and Veterans: What are the differences between PTS and PTSD. Available online: https://www.brainline.org/article/what-are-differences-between-pts-and-ptsd#:~:text=PTS%20symptoms%20are%20common%20after,PTSD%20without%20first%20having%20PTS (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Henson, C.; Truchot, D.; Canevello, A. What promotes posttraumatic growth? A systematic review. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2021, 5, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.; Lakshmi, U.; Watson, H.; Ismail, A.; Sherrill, A.M.; Kumar, N.; Arriaga, R.I. Understanding the Care Ecologies of Veterans with PTSD. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, J.B.; Benuto, L.T. Work-related traumatic stress spillover in first responder families: A systematic review of the literature. Psychol. Trauma 2022, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue: Toward a new understanding of the cost of caring. In Secondary Traumatic Stress; Stamm, B.H., Ed.; Sidran Institute: Towson, MD, USA, 1999; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Regehr, C.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Bright, E.; George, S.; Henderson, J. Behind the brotherhood: Rewards and challenges for wives of firefighters. Fam. Relat. 2005, 54, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L. Police families: Stresses, syndromes, and solutions. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2007, 35, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshtriya, S.; Kobezak, H.; Popok, P.; Lawrence, J.; Lowe, S. Social support as a mediator of occupational stressors and mental health outcomes in first responders. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 2252–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Goldstein, M.B.; Malley, J.C.; Rivers, A.J.; Johnson, D.C.; Morgan, C.A., III; Southwick, S.M. Posttraumatic growth in veterans of operations enduring freedom and Iraqi freedom. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 126, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.; Teixeira, F.; Neto, F.; Maia, Â. Peer support in prehospital emergency: The first responders’ point of view. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2020, 10, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavustra, A.; Cloitre, M. Social bonds and post-traumatic stress disorder. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, L. The state of crisis. In Crisis Intervention; Parad, H., Ed.; Family Service Association of America: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, M.; Mulhall, C.; Eppich, W. Breaking down barriers to help-seeking: Preparing first responders’ families for psychological first aid. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2022, 13, 2065430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, S.B.; Pennington, M.L.; Torres, V.A.; Steffen, L.E.; Mardikar, A.; Leto, F.; Ostiguy, W.; Zimering, R.T.; Kimbrel, N.A. Behavioral health programs in fire service: Surveying access and preferences. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, A.; Steel, Z.; Ward, P.B.; Boydell, K.M.; McKeon, G.; Rosenbaum, S. Trauma and Mental Health Awareness in Emergency Service Workers: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Behind the Seen Education Workshops. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.S. Work Stress and Social Support; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.; Norris, D.; Cramm, H.; Richmond, R.; Anderson, G.S. Public safety personnel family resilience: A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology: Preparedness. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/preparedness (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Lingard, L. Writing an effective literature review. Part 1: Mapping the gap. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2018, 7, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Wr. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Petrie, K.; Deady, M.; Bryant, R.A.; Harvey, S.B. Systematic review of first responder post-deployment or post-incident psychosocial interventions. Occup. Med. 2022, 72, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, R.C.; Slevín, R.A.; Chang, B.P.; Sano, E.; McCall, C.; Raskind, M.A. The impact of working during the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers and first responders: Mental health, function, and professional retention. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, J. Iterative categorization (IC): A systematic technique for analysing qualitative data. Addiction 2016, 111, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.; Kajamaa, A.; Johnston, J. How to be reflexive when conducting qualitative research. Clin. Teach 2020, 17, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; Johnson, L.B.; Nieva, R. Occupational stress: Coping of police and their spouses. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beks, T. Walking on Eggshells: The Lived Experience of Partners of Veterans with PTSD. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrow, J.; Cook, E.; Knowles, C.; Vieten, C. Coming all the way home: Integrative community care for those who serve. Psych. Serv. 2013, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochantin, J.E. “Ambulance Thieves, Clowns, and Naked Grandfathers” How PSEs and Their Families Use Humorous Communication as a Sensemaking Device. Manag. Commun. Q 2017, 31, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, C.; Kemppainen, J.; Smith, S.; MacKain, S.; Cox, C.W. Awareness of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: A female spouse/intimate partner perspective. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, K.; Liu, J.J.; Cramm, H.; Nazarov, A.; Hunt, R.; Forchuk, C.; Richardson, J.D.; Deda, E. “You can’t un-ring the bell”: A mixed methods approach to understanding veteran and family perspectives of recovery from military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. BMC Psych. 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ewles, G. Enhancing Organizational Support for Emergency First Responders and their Families: Examining the Role of Personal Support Networks after the Experience of Work-Related Trauma. Doctoral Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Folwell, A.; Kauer, T. You see a baby die and you’re not fine: A case study of stress and coping strategies in volunteer emergency medical technicians. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2018, 46, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, K.M. Cuffed together: A study on how law enforcement work impacts the officer’s spouse. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 2020, 22, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Sundin, E.; Winder, B. Work–family enrichment of firefighters: Satellite family members”, risk, trauma and family functioning. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2020, 9, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, T.A. Warrior resilience and thriving (WRT): Rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) as a resiliency and thriving foundation to prepare warriors and their families for combat deployment and posttraumatic growth in Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2005–2009. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. 2013, 31, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, A.L.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Mendenhall, T.J.; Kennedy, A.; Zemanek, L. Backing the blue: Trauma in law enforcement spouses and couples. Fam. Relat. 2020, 69, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, P.; Saltzman, W.R.; Woodward, K.; Glover, D.; Leskin, G.A.; Bursch, B.; Beardslee, W.; Pynoos, R. Evaluation of a family-centered prevention intervention for military children and families facing wartime deployments. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, S48–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, G.; Mastrogiovanni, C.; Chapman, J.; Stanton, R.; Matthews, E.; Steel, Z.; Rosenbaum, S.; Wells, R. The experiences of peer-facilitators delivering a physical activity intervention for emergency service workers and their families. MENPA 2021, 21, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, G.; Wells, R.; Steel, Z.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Teasdale, S.; Vancampfort, D.; Rosenbaum, S. An online mental health informed physical activity intervention for emergency service workers and their families: A stepped-wedge trial. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, A.M.; Molloy, J.; Magaldi, M.C. Health responses of New York City firefighter spouses and their families post-September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2006, 27, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, K.L.; Henriksen, R.C., Jr. The phenomenological experience of first responder spouses. Fam. J. 2016, 24, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.G.; Moore, C.D. Work-family fit: The impact of emergency medical services work on the family system. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2009, 13, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltzman, W.R. The FOCUS family resilience program: An innovative family intervention for trauma and loss. Fam. Process 2016, 55, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd-Banigan, M.; Smith, V.A.; Stechuchak, K.M.; Van Houtven, C.H. Informal Caregiver Support Policies Change Use of Vocational Assistance Services for Individuals With Disabilities. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekin, S.; Glover, N.; Greene, T.; Lamb, D.; Murphy, D.; Billings, J. Experiences and views of frontline healthcare workers’ family members in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2022, 13, 2057166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, E.; Lawn, S.; Roberts, L.; Henderson, J.; Venning, A.; Redpath, P. “Why do you stay?”: The lived-experience of partners of Australian veterans and first responders with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1734–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, M.L.; Solomon, N.; Harrison, V.; Gribble, R.; Cramm, H.; Pike, G.; Fear, N.T. The mental health and wellbeing of spouses, partners and children of emergency responders: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Trusted others (family member, partner, spouse, friend, or care-partner) of first responders. | Non-family member, partner, spouse, friend, or care-partner (e.g., clinician, counselor). |

| First responders (military, veteran, law enforcement officer, fire fighter, paramedic or EMT, and frontline health care professional (physician and nurse practitioner)). | Non-first responders or frontline healthcare professionals. | |

| Study Focus | Studies describing support strategies, coping mechanisms, training interventions, programs, or practices utilized by the trusted others of first responders. | Studies that do not acknowledge trusted others’ involvement in supporting first responders. Studies that do not describe trusted others’ social support provision, resource utilization, and barriers encountered in providing social support. |

| Studies describing trusted others’ resource preference and availability (informal and formal), barriers, and limitations encountered in providing social support. | ||

| Study Type | Qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methodologies, book chapters, thesis dissertations, and grey literature, including intervention protocols and manuals. | Literature reviews, review articles, reports, and conference papers were used to identify additional literature only. |

| Publication Characteristics | All countries, English language, full-text available, not restricted by publication date. | Non-English studies, no full-text available. |

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Sample/Subject (Country) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beehr et al. (1995) [36] | Quantitative | 177 police officers and partners (USA) |

|

| Beks (2016) [37] | Qualitative | 30 female partners of veterans (Canada) |

|

| Bobrow et al. (2012) [38] | Quantitative | 347 veterans, military service members, and family (USA) |

|

| Bochantin (2017) [39] | Qualitative | 18 police officers, 18 firefighters, and 107 family members and spouses (USA) |

|

| Buchanan et al. (2011) [40] | Qualitative | 34 spouses/partners of veterans (USA) |

|

| Casas & Benuto (2022) [12] | Systematic review | 904 FRs, 903 family members (USA) |

|

| Cyr et al. (2022) [41] | Mixed methods | 16 veterans and partners (Canada) |

|

| Evans et al. (2020) [11] | Qualitative | 21 veterans and trusted others (USA) |

|

| Ewles (2019) [42] | Mixed methods | 38 police officers and partners, and 179 FRs (Canada) |

|

| Folwell & Kauer (2018) [43] | Qualitative | 25 EMS (USA) |

|

| Friese (2020) [44] | Mixed methods | 171 law enforcement officer spouses/partners (USA) |

|

| Hill et al. (2020) [45] | Qualitative | 10 family members of the fire and rescue services personnel (UK) |

|

| Jarrett (2013) [46] | Mixed-methods: Program evaluation | Soldiers and family members (USA) |

|

| Landers et al. (2020) [47] | Qualitative | 8 spouses of law enforcement officers (Canada) |

|

| Lester et al. (2012) [48] | Quantitative | 331 military families (USA) |

|

| McKeon et al. (2021) [49] | Quantitative | 34 EMS workers and 30 partners (Australia) |

|

| McKeon et al. (2022) [50] | Quantitative | 47 EMS workers and 43 partners (Australia) |

|

| Menendez et al. (2006) [51] | Qualitative | 26 spouses of firefighters (USA) |

|

| Porter and Henriksen (2016) [52] | Qualitative | 6 spouses of first responders (USA) |

|

| Roth & Moore (2009) [53] | Qualitative | 14 spouses and parents of EMS workers (USA) |

|

| Saltzman et al. (2016) [54] | Program description | Case examples of trusted others dealing with trauma (USA) |

|

| Shepherd-Banigan et al. (2022) [55] | Quantitative | Secondary analysis of administrative US veteran affairs data (USA) |

|

| Tekin et al. (2022) [56] | Qualitative | 14 family members of frontline healthcare professionals (UK) |

|

| Waddell et al. (2020) [57] | Qualitative | 10 partners of veterans (Australia) |

|

| Main Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Providing Support | |

| Emotional support |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Instrumental support |

|

| |

| |

| Appraisal support |

|

| |

| |

| Informational support |

|

| Finding Support | |

| Formal |

|

| |

| Informal |

|

| |

| Support needed | |

| Inadequate communication skills | Difficulties in having difficult conversations with first responders after a critical incident. |

| Maladaptive coping strategies | Hyper-masculinity, avoidant coping, withdrawal, compartmentalizing, disempowering beliefs, substance abuse. |

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Emotional support | The provision of trust, empathy, love, and care |

| Instrumental support | The provision of tangible services, goods, or aid |

| Appraisal support | The provision of affirmation or communication of information that is relevant for self-evaluation |

| Informational support | The provision of knowledge and information |

| Area | Actions |

|---|---|

| Practical support [41,49,54,56] |

|

| Assessment and treatment [11,38,39,41,43,50] |

|

| Organizational support [39,40,41,45,50,51,52,53,55,56] |

|

| Information and training [38,40,41,43,45,47,48,49,51,52,53] |

|

| Social support [41,42,45,48,49,52,57] |

|

| Lifestyle intervention [37,45,46,52] |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tjin, A.; Traynor, A.; Doyle, B.; Mulhall, C.; Eppich, W.; O’Toole, M. Turning to ‘Trusted Others’: A Narrative Review of Providing Social Support to First Responders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416492

Tjin A, Traynor A, Doyle B, Mulhall C, Eppich W, O’Toole M. Turning to ‘Trusted Others’: A Narrative Review of Providing Social Support to First Responders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416492

Chicago/Turabian StyleTjin, Anna, Angeline Traynor, Brian Doyle, Claire Mulhall, Walter Eppich, and Michelle O’Toole. 2022. "Turning to ‘Trusted Others’: A Narrative Review of Providing Social Support to First Responders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416492

APA StyleTjin, A., Traynor, A., Doyle, B., Mulhall, C., Eppich, W., & O’Toole, M. (2022). Turning to ‘Trusted Others’: A Narrative Review of Providing Social Support to First Responders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416492