An Assessment of Vape Shop Products in California before and after Implementation of FDA and State Regulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

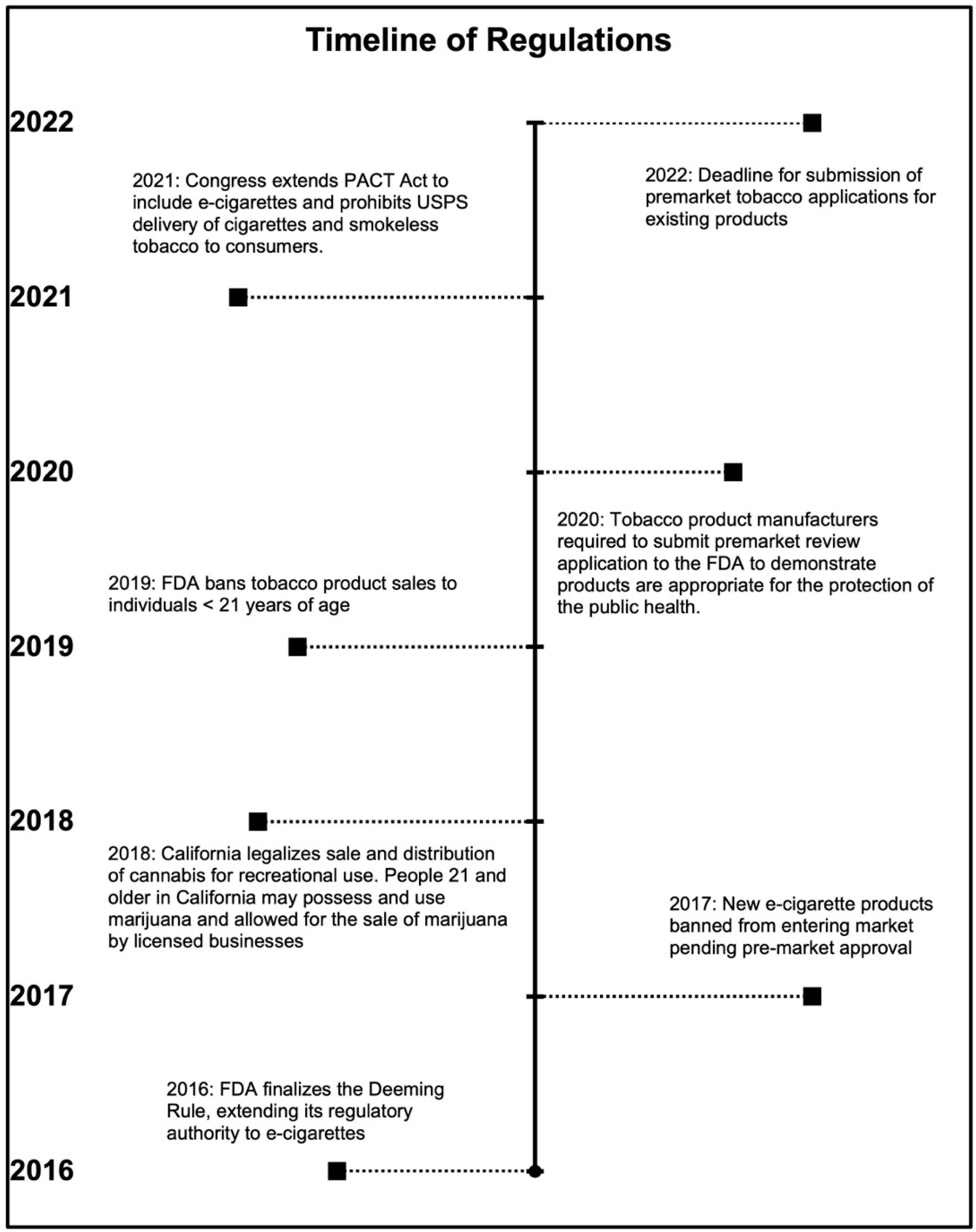

1.1. Federal Regulations

1.1.1. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Deeming Rule

1.1.2. The E-Cigarette Flavor Ban

1.1.3. The U.S. Preventing All Cigarette Trafficking (PACT) Act

1.2. California State Regulations

1.2.1. California Proposition 64: The Adult Use of Marijuana Act

1.2.2. E-Cigarette Products

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Sample Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection across the Four Waves

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. E-Cigarette Products

3.2. Customer Amenities

3.3. Other Products

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2016. Chapter 4, Activities of the E-Cigarette Companies. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538679/ (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Rose, S.W.; Barker, D.C.; D’Angelo, H.; Khan, T.; Huang, J.; Chaloupka, F.J.; Ribisl, K.M. The availability of electronic cigarettes in US retail outlets, 2012: Results of two national studies. Tobacco Control 2014, 23 (Suppl. S3), iii10–iii16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.G.L.; Orlan, E.N.; Sewell, K.B.; Ribisl, K.M. A new form of nicotine retailers: A systematic review of the sales and marketing practices of vape shops. Tob. Control 2018, 27, e70–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galimov, A.; Meza, L.; Unger, J.B.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Cruz, T.B.; Sussman, S. Vape Shop Employees: Do They Act as Smoking Cessation Counselors? Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2021, 23, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, S.; Garcia, R.; Cruz, T.B.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Pentz, M.A.; Unger, J.B. Consumers’ perceptions of vape shops in Southern California: An analysis of online Yelp reviews. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2014, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allem, J.-P.; Unger, J.B.; Garcia, R.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S. Tobacco Attitudes and Behaviors of Vape Shop Retailers in Los Angeles. Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galimov, A.; Galstyan, E.; Yu, S.; Smiley, S.L.; Meza, L.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Unger, J.B.; Sussman, S. Predictors of Vape Shops Going out of Business in Southern California. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2020, 6, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, J.; Meza, L.R.; Galstyan, E.; Galimov, A.; Unger, J.B.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S. Association between federal and California state policy violation among vape shops and neighbourhood composition in Southern California. Tob. Control 2021, 30, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Deeming Tobacco Products to Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products; Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco Products: Vaporizers, E-Cigarettes, and Other Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS). 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/e-cigarettes-vapes-and-other-electronic-nicotine-delivery-systems-ends (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Meza, L.; Galimov, A.; Huh, J.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S. Compliance to FDA’s elimination of free tobacco product sampling at vape shops. Addict. Behav. 2022, 125, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Federal Regulations-Title 21-Food and Drugs. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-databases/code-federal-regulations-title-21-food-and-drugs#:~:text=Code%20of%20Federal%20Regulations%20-%20Title%2021%20-,for%20rules%20of%20the%20Food%20and%20Drug%20Administration (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Tobacco Free Nicotine (TFN): A New Public Health Challenge—Blog—Tobacco Control. (n.d.). Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2021/07/03/tobacco-free-nicotine-tfn-a-new-public-health-challenge/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Zettler, P.; Hemmerich, N.; Berman, M. Closing the Regulatory Gap for Synthetic Nicotine Products. Boston Coll. Law Rev. 2018, 59, 1933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking (PACT) Act | Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.atf.gov/alcohol-tobacco/prevent-all-cigarette-trafficking-pact-act (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Vapes and E-Cigarettes | Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.atf.gov/alcohol-tobacco/vapes-and-e-cigarettes (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Baker, H.M.; Lee, J.G.L.; Ranney, L.M.; Goldstein, A.O. Discrepancy in Self-Report “Loosie” Use and Federal Compliance Checks. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, Z.; Drope, J.; Douglas, C.E.; Henson, R.; Berg, C.J.; Ashley, D.L.; Eriksen, M.P. Applying the Population Health Standard to the Regulation of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- California Cannabis General Provisions. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=BPC&division=10.&title=&part=&chapter=1.&article= (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- California Proposition 64: The Adult Use of Marijuana Act. 2016. Available online: https://www.courts.ca.gov/prop64.htm (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- California, S. of. (n.d.). California’s Cannabis Laws. Department of Cannabis Control. Available online: https://cannabis.ca.gov/cannabis-laws/laws-and-regulations/ (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Leas, E.C.; Nobles, A.L.; Shi, Y.; Hendrickson, E. Public interest in ∆8-Tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-8-THC) increased in US states that restricted ∆9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-9-THC) use. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 101, 103557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, C.J.; Stratton, E.; Schauer, G.L.; Lewis, M.; Wang, Y.; Windle, M.; Kegler, M. Perceived Harm, Addictiveness, and Social Acceptability of Tobacco Products and Marijuana Among Young Adults: Marijuana, Hookah, and Electronic Cigarettes Win. Subst. Use Misuse 2015, 50, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan-Atrash, J.; Rahman, I. Novel Δ 8 -Tetrahydrocannabinol Vaporizers Contain Unlabeled Adulterants, Unintended Byproducts of Chemical Synthesis, and Heavy Metals. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, R.L.; Groom, A.L.; Vu, T.-H.T.; Stokes, A.C.; Berry, K.M.; Kesh, A.; Hart, J.L.; Walker, K.L.; Giachello, A.L.; Sears, C.G.; et al. The role of flavors in vaping initiation and satisfaction among U.S. adults. Addict. Behav. 2019, 99, 106077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romm, K.F.; Henriksen, L.; Huang, J.; Le, D.; Clausen, M.; Duan, Z.; Fuss, C.; Bennett, B.; Berg, C.J. Impact of existing and potential e-cigarette flavor restrictions on e-cigarette use among young adult e-cigarette users in 6 US metropolitan areas. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 28, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galstyan, E.; Galimov, A.; Sussman, S. Commentary: The Emergence of Pod Mods at Vape Shops. Eval. Health Prof. 2019, 42, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galimov, A.; Leventhal, A.; Meza, L.; Unger, J.B.; Huh, J.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S.Y. Prevalence of disposable pod use and consumer preference for e-cigarette product characteristics among vape shop customers in Southern California: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.Y.; Eaddy, J.L.; Morrison, S.L.; Asbury, D.; Lindell, K.M.; Ribisl, K.M. Using the Vape Shop Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Settings (V-STARS) to Assess Product Availability, Price Promotions, and Messaging in New Hampshire Vape Shop Retailers. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2017, 3, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.Y.; Bluthenthal, R.; Allem, J.P.; Garcia, R.; Garcia, J.; Unger, J.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S.Y. Vape shop retailers’ perceptions of their customers, products and services: A content analysis. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2016, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.J.; Barker, D.C.; Sussman, S.; Getachew, B.; Pulvers, K.; Wagener, T.L.; Hayes, R.B.; Henriksen, L. Vape Shop Owners/Managers’ Opinions About FDA Regulation of E-Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siahpush, M.; Shaikh, R.; Smith, D.; Hyland, A.; Cummings, K.; Kessler, A.; Dodd, M.; Carlson, L.; Meza, J.; Wakefield, M. The Association of Exposure to Point-of-Sale Tobacco Marketing with Quit Attempt and Quit Success: Results from a Prospective Study of Smokers in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L.; Glasser, A.M.; Abudayyeh, H.; Pearson, J.L.; Villanti, A.C. E-Cigarette Marketing anCommunication: How E-Cigarette Companies Market E-Cigarettes and the Public Engages with E-cigarette Information. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, L.; McGee, R.; Marsh, L.; Hoek, J. A Systematic Review on the Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Promotion on Smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiton, M.O.; Mecredy, G.; Cohen, J. Tobacco retail availability and risk of relapse among smokers who make a quit attempt: A population-based cohort study. Tob. Control 2018, 27, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.J.; Melena, A.; Wittman, F.D.; Robles, T.; Henriksen, L. The Reshaping of the E-Cigarette Retail Environment: Its Evolution and Public Health Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.; Barker, D.C.; Huang, J.; Kemp, C.B.; Wagener, T.L.; Chaloupka, F. ‘No, the government doesn’t need to, it’s already self-regulated’: A qualitative study among vape shop operators on perceptions of electronic vapor product regulation. Health Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Jiang, S.; Ling, M.; Chen, J.; Shang, C. Price Promotions of E-Liquid Products Sold in Online Stores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.J.; Barker, D.C.; Meyers, C.; Weber, A.; Park, A.J.; Patterson, A.; Dorvil, S.; Fairman, R.T.; Huang, J.; Sussman, S.; et al. Exploring the Point-of-Sale Among Vape Shops Across the United States: Audits Integrating a Mystery Shopper Approach. Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2021, 23, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadus, M.C.; Smith, T.T.; Squeglia, L.M. The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: Factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 201, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgili, F.; Nenna, R.; Ben David, S.; Mancino, E.; Di Mattia, G.; Matera, L.; Petrarca, L.; Midulla, F. E-cigarettes and youth: An unresolved Public Health concern. Ital. J. Pediatrics 2022, 48, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu, D.; Huang, J.; Weaver, S.R.; Pechacek, T.F.; Ashley, D.L.; Nayak, P.; Eriksen, M.P. Patterns and trends of dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes among U.S. adults 2015–2018. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 16, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wave 1 (N = 77) | Wave 2 * (N = 61) | Wave 3 * (N = 122) | Wave 4 ** (N = 85) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette Products | ||||

| Disposable Devices | 14 (18.2%) | 6 (9.8%) | 11 (9.0%) | 84 (98.8%) |

| Atomizers | 76 (98.7%) | 60 (98.4%) | 119 (97.5%) | 77 (90.5%) |

| Mouth tips | 76 (98.7%) | 60 (98.4%) | 111 (91.0%) | N/A |

| Pod Mod Devices | N/A | N/A | 97 (79.5%) | 82 (96.5%) |

| Wires/Coils | 10 (13.0%) | 40 (65.6%) | 90 (73.8%) | 44 (51.8%) |

| Customer Amenities | ||||

| Self-Service E-juice Display | 64 (83.1%) | 54 (88.5%) | 13 (10.7%) | 8 (9.0%) |

| Drills Available in Shop | 46 (60.0%) | 37 (60.7%) | 20 (16.4%) | 0 |

| Other Products | ||||

| Glass pipes, bongs, etc. | 0 | 0 | 26 (21.0%) | 26 (30.5%) |

| CBD | 0 | 0 | 23 (19.0%) | 62 (72.9%) |

| Delta 8/9-THC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (10.6%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galstyan, E.; Galimov, A.; Meza, L.; Huh, J.; Berg, C.J.; Unger, J.B.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S. An Assessment of Vape Shop Products in California before and after Implementation of FDA and State Regulations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315827

Galstyan E, Galimov A, Meza L, Huh J, Berg CJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Sussman S. An Assessment of Vape Shop Products in California before and after Implementation of FDA and State Regulations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315827

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalstyan, Ellen, Artur Galimov, Leah Meza, Jimi Huh, Carla J. Berg, Jennifer B. Unger, Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, and Steve Sussman. 2022. "An Assessment of Vape Shop Products in California before and after Implementation of FDA and State Regulations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315827

APA StyleGalstyan, E., Galimov, A., Meza, L., Huh, J., Berg, C. J., Unger, J. B., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., & Sussman, S. (2022). An Assessment of Vape Shop Products in California before and after Implementation of FDA and State Regulations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315827