Health Promotion on Instagram: Descriptive–Correlational Study and Predictive Factors of Influencers’ Content

Abstract

1. Introduction and Literature Review

Social Networks and Health

- Difficulty in searching for and critically selecting reliable information.

- Lack of judgement and tools to obtain accurate information in the right format and at the right time.

- Unawareness of the usage and relevance of health-related digital applications.

- To describe the contents of self-proclaimed health influencers on Instagram and their authors, as well as to identify their main followers (age and gender profile).

- Determine the extent to which these accounts provide genuine health content to verify whether, as profiles that disseminate health information, they promote health to a high degree.

- Determine what factors (gender and age range of the influencer and predominant gender of their followers) influence the publication of health content on these accounts.

2. Method and Data Collection

- Content not related to health. Groups together all categories of the “content” variable that do not refer to health-related aspects (e.g., brands, normative bodies, beautiful person, memes and virals, swimwear or underwear, etc.). Value assumed by this category of the variable: 0.

- Health-related content. Groups the following categories of the “content” variable: (1) healthy food, (2) unhealthy food, (3) health tips, (4) pregnancy, (5) sport and (6) hospital environment. Value assumed by this category: 1.

3. Results

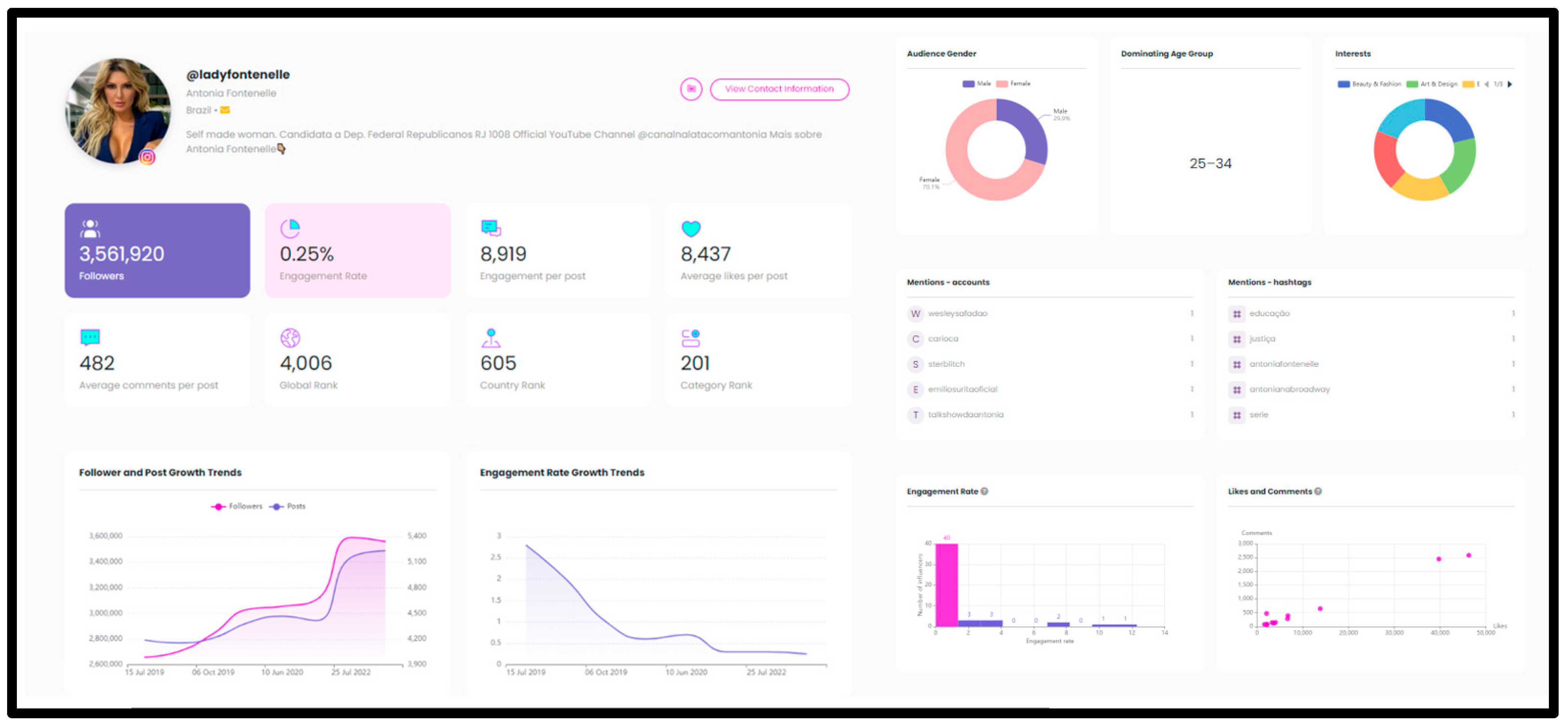

3.1. General Data

3.2. Content Analysis

3.3. Correlational Study and Predictive Factors of the Type of Content

- Highly significant correlations are observed in a positive sense (although with weak intensity) between gender and the presence of health content (rho(1398) = 0.102 p = 0.001). In this case, the fact that the influencer is male is significantly associated with the publication of health-related content.

- Again, the calculations also find a highly significant positive (but equally weak) correlation between accounts with a majority of followers aged between 25 and 34 and the publication of health-related content (rho(1398) = 0.120 p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gabelas Barroso, J.A.; Marta Lazo, C. La era TRIC: Factor R-elacional y educomunicación. Ediciones Egregius. Estud. Sobre Mensaje Periodístico 2020, 27, 1001–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Tyner, K. Educación para los medios, alfabetización mediática y competencia digital. Comunicar 2012, 38, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, E.; Gaspar, J.; Gabel, J. The Qustodio Annual Data Report 2021. Living and Learning in a Digital World. The Complete Snapshot of How Children Are Living and Growing with Technology. 2022. Available online: https://static.qustodio.com/public-site/uploads/ADR_2022_en_040422.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Smahel, D.; Machackova, H.; Mascheroni, G.; Dedkova, L.; Staksrud, E.; Ólafsson, K.; Livingstone, S.; Hasebrink, U. EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, C.; Sanz-Marcos, P. Estrategia de marca, influencers y nuevos públicos en la comunicación de moda y lujo. Tendencia Gucci en Instagram. Prism. Soc. 2019, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Peco, I. Comunicación en salud y redes sociales: Necesitamos más enfermeras. Rev. Científica Soc. Española Enfermería Neurológica 2021, 53, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaga, A.; Aker, A.; Bontcheva, K.; Liakata, M.; Procter, R. Detection and resolution of rumours in social media: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gupta, A.; Kauten, C.; Deokar, A.V.; Qin, X. Detecting fake news for reducing misinformation risks using analytics approaches. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 1036–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierri, F.; Artoni, A.; Ceri, S. Investigating Italian disinformation spreading on Twitter in the context of 2019 European elections. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Castaño, L. Jugando a ser influencers: Un estudio comparativo entre jóvenes españoles y colombianos en Instagram. Commun. Soc. 2022, 35, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymerich, L.; Fedele, M. La implementación de los Social Media como recurso docente en la universidad presencial: La perspectiva de los estudiantes de Comunicación. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2015, 13, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.; Ferrer, R.; De la Herrán, A. Las redes sociales verticales en los sistemas formales de formación inicial de docentes. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2015, 26, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, B.; Guadix, I.; Rial, A.; Suárez, F. Impacto De La Tecnología En La Adolescencia. Relaciones, Riesgos Y Oportunidades; UNICEF España: Madrid, España, 2021; Available online: https://www.unicef.es/sites/unicef.es/files/comunicacion/Informe_Impacto_de_la_tecnologia_en_la_adolescencia.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Feijoo, B.; Sádaba, C. When mobile advertising is interesting: Interaction of minors with ads and influencers’ sponsored content on social media. Commun. Soc. 2022, 35, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Martín, A.; Pinedo-González, R.; Gil-Puente, C. Competencias TIC y mediáticas del profesorado.: Convergencia hacia un modelo integrado AMI-TIC. Comun. Rev. Científica Iberoam. Comun. Educ. 2022, 70, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.; Xiao, X. The importance of ’likes’: The interplay of message framing, source, and social endorsement on credibility perceptions of health information on Facebook. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Romo, Z.F.; Iriarte Aguirre, S. Análisis de la gestión de la comunicación de los influencers farmacéuticos españoles en Instagram durante la pandemia del COVID-19. Rev. Española Comun. Salud 2020, 1, S9–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K. Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media Soc. 2018, 21, 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, C.C.; Lemon, L.L.; Hoy, M.G. #Sponsored #Ad: Agency Perspective on Influencer Marketing Campaigns. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2018, 40, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Hudders, L. Disclosing sponsored Instagram posts: The role of material connection with the brand and message-sidedness when disclosing covert advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 39, 94–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubb, C.; Nyström, A.G.; Colliander, J. Influencer marketing: The impact of disclosing sponsorship compensation justification on sponsored content effectiveness. J. Commun. Manag. 2019, 23, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubb, C.; Colliander, J. "This is not sponsored content"—The effects of impartiality disclosure and e-commerce landing pages on consumer responses to social media influencer posts. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 98, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rico, C.M.; González-Esteban, J.L.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Consumo de información en redes sociales durante la crisis de la COVID-19 en España. Rev. Comun. Salud 2020, 10, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Martínez, A.; Méndez-Domínguez, P.; Sosa, A.; Castillo de Mesa, J. Social connectivity, sentiment and participation on Twitter during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Sánchez, C.; López-García, X. Comunicación y crisis del coronavirus en España. Primeras lecciones. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallotti, R.; Valle, F.; Castaldo, N.; Sacco, P.; De Domenico, M. Assessing the risks of ‘infodemics’ in response to COVID-19 epidemics. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparici, R.; García-Marín, D.; Rincón-Manzano, L. Noticias falsas, bulos y trending topics. Anatomía y estrategias de la desinformación en el conflicto catalán. Prof. Inf. 2019, 28, e280313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marín, D. Infodemia global. Desórdenes informativos, narrativas fake y fact-checking en la crisis de la Covid-19. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Saisó, S.; Marti, M.; Brooks, I.; Curioso, W.H.; González, D.; Malek, V.; Mejía Medina, F.; Radix, C.; Otzoy, D.; Zacarías, S.; et al. Infodemia en tiempos de COVID-19. Rev Panam Salud Pública 2021, 45, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, N.; Harris, I.; Frank, G.; Kiptanui, Z.; Qian, J.; Hansen, R. Influencers of generic drug utilization: A systematic review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Marín, G.; Bellido-Pérez, E.; Trujillo Sánchez, M. Publicidad en Instagram y riesgos para la salud pública: El influencer no sanitario como prescriptor de medicamentos, a propósito de un caso. Rev. Española Comun. Salud 2021, 12, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Sánchez, L.; de Frutos-Torres, B.; Gutiérrez-Martín, A. La COVID-19 en la prensa española. Encuadres de alarma y tranquilidad en las portadas de El País, El Mundo y La Vanguardia. Rev. Comun. Salud 2020, 10, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Benito, S.; Elorriaga-Illera, A.; Olabarri-Fernández, E. YouTube celebrity endorsement: Audience evaluation of source attributes and response to sponsored content. A case study of influencer Verdeliss. Commun. Soc. 2020, 33, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrego, A.; Gutiérrez-Martín, A.; Hoechsmann, M. The fine line between person and persona in the Spanish reality television show La Isla de las tentaciones: Audience engagement on Instagram. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Santos-Roldán, L.M.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impacto del riesgo percibido en las recomendaciones de producto de los influencers sobre las actitudes e intención de compra de sus seguidores. Previs. Tecnológica Cambio Soc. 2022, 184, 121997. [Google Scholar]

- Herzallah, D.; Leiva, F.M.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. To Buy or Not to Buy, That Is the Question: Understanding the Determinants of the Urge to Buy Impulsively on Instagram Commerce. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCosker, A.; Gerrard, Y. Hashtagging Depression on Instagram: Towards a More Inclusive Mental Health Research Methodology. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 1899–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrow-Young, A. Approaching Instagram Data: Reflections on Accessing, Archiving and Anonymising Visual Social Media. Commun. Res. Pract. 2021, 7, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Sezerel, H.; Uzuner, Y. Sharing Experiences and Interpretation of Experiences: A Phenomenological Research on Instagram Influencers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 3034–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.M.; Garcia, D.J.; de Faria, D.S.; Fidalgo-Neto, A.A.; Mota, F.B. Facebook in Educational Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1591–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segado-Boj, F. Research on Social Media and Journalism (2003–2017): A Bibliometric and Content Review. Transinformação 2020, 32, e180096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.; Suki, N.M.; Suki, N.M. Evolution Trends of Facebook Marketing in Digital Economics Growth: A Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. IJIM 2021, 15, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Si, S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y. A Review of Enterprise Social Media: Visualization of Landscape and Evolution. Internet Research 2021, 31, 1203–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Nanda, P.; Tawangar, S. Social Media in Business Decisions of MSMEs: Practices and Challenges. Int. J. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardus, M.; El Rassi, R.; Chahrour, M.; Akl, E.W.; Raslan, A.S.; Meho, L.I.; Akl, E.A. The use of social media to increase the impact of health research: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulos, K.; Maged, N.; Giustini, D.M.; Wheeler, S. Instagram and WhatsApp in health and healthcare: An overview. Future Internet 2016, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, M.; Connelly, J.; Priscilla Clayton, C.; Lorenzo, Y.; Collazo-Velazquez, C.; Trak-Fellermeier, M.A.; Palacios, C. Use of Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter for Recruiting Healthy Participants in Nutrition, Physical Activity, or Obesity Related Studies: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 115, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, A.W.; Kan, A.T.; Klager, E.; Eibensteiner, F.; Tsagkaris, C.; Parvanov, E.D.; Nawaz, F.A.; Völkl-Kernstock, S.; Schaden, E.; Kletecka-Pulker, M.; et al. Medical and Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media: Bibliometric Study of the Scientific Literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e28152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Sweileh, W.M.; Awang, R.; Al-Jabi, S.W. Global trends in research related to social media in psychology: Mapping and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Mental Health Syst. 2018, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faelens, L.; Hoorelbeke, K.; Cambier, R.; van Put, J.; Van de Putte, E.; De Raedt, R.; Koster, E.H.W. The Relationship between Instagram Use and Indicators of Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Uddin, Z.A.; Lee, Y.; Nasri, F.; Gill, H.; Subramanieapillai, M.; Lee, R.; Udovica, A.; Phan, L.; Lui, L.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Validity of Screening Depression through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 286, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Meier, A.; Beyens, I. Social Media Use and Its Impact on Adolescent Mental Health: An Umbrella Review of the Evidence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardo, J.; McKenzie, S.K.; Collings, S.; Jenkin, G. Suicide and Self-Harm Content on Instagram: A Systematic Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Page Starngage. Available online: https://starngage.com/plus/en-us (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Ging, D.; Garvey, S. ’Written in these scars are the stories I can’t explain’: A content analysis of pro-ana and thinspiration image sharing on Instagram. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 1181–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, N.H.; Willoughby, J.F. Photo-sharing social media for eHealth: Analysing perceived message effectiveness of sexual health information on Instagram. J. Vis. Commun. Med. 2017, 40, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Sun, Y.; McLaughlin, M.L. Social media propagation of content promoting risky health behavior. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, C. Adolescents’ Food Communication in Social Media. In Advanced Methodologies and Technologies in Media and Communications; Khosrow-Pour, M.D.B.A., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, N.A.; Hartung, C.; Welch, R. Health education, social media, and tensions of authenticity in the ’influencer pedagogy’ of health influencer Ashy Bines. Learn. Media Technol. 2021, 47, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durau, J.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R. Motivate me to exercise with you: The effects of social media fitness influencers on users’ intentions to engage in physical activity and the role of user gender. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, V.Y. "Sadfishing": Nueva Tendencia De Espectacularización De La Depresión En TikTok, Análisis De Influencers; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2022; Available online: https://repositorioslatinoamericanos.uchile.cl/handle/2250/4568878?show=full (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- García Rivero, A.; Estrella, C.M.; Bonales, D.E.G. TikTok y Twitch: New Media and Formulas to Impact the Generation Z. Icono 2022, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalan-Matamoros, D.; Elías, C. Vaccine Hesitancy in the Age of Coronavirus and Fake News: Analysis of Journalistic Sources in the Spanish Quality Press. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sanz, R.; Buitrago, Á.; Martín-García, A. Comunicación para la salud a través de TikTok. Estudio de influencers de temática farmacéutica y conexión con su audiencia. Rev. Mediterránea Comun. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Ordóñez, C.; Castro-Martínez, A. Creadores de contenido especializado en salud en redes sociales. Los micro influencers en Instagram. Rev. Comun. Salud 2022, 13, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Acedo, S.; Gil-Quintana, J.; Cantillo Valero, C. La construcción de la identidad infantil en el Mundo Disney. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 1284–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzle, A.; Wilson, C.; Tuazon, R.; Cheung, C.K.; Lau, J.; Fischer, R.; Ggrdon, D.; Akyempong, K.; Singh, J.; Carr, P.R.; et al. Media & Information Literacy Curriculum For Educators & Learners; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category |

|---|---|

| 1. Influencer gender | Male Female |

| 2. % female followers | Quantitative variable |

| 3. % male followers | Quantitative variable |

| 4. Follower’s interests * | Beauty Music Fitness Travel Business Art and design Children and family Cars Entertainment Food and restaurants Movies and TV Sports Photography Not identified |

| 5. Follower age range | 18–24 years 25–34 years |

| 6. Content published by the influencer | Brands Normative body Healthy foods Unhealthy foods Health tips Swimwear or underwear Eroticism Beautiful person Non-normative body Family Pregnancy Sport Beauty tips Memes and virals Bodybuilding Hospital environment Cooking recipes Other |

| Other Follower Interests | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Beauty | 213 | 48.1 |

| Music | 18 | 4.1 |

| Fitness | 57 | 12.9 |

| Travel | 7 | 1.6 |

| Business | 1 | 0.2 |

| Art and design | 12 | 2.7 |

| Children and family | 13 | 2.9 |

| Cars | 2 | 0.5 |

| Entertainment | 26 | 5.9 |

| Food and restaurants | 18 | 4.1 |

| Movies and TV | 12 | 2.7 |

| Sports | 2 | 0.5 |

| Photography | 1 | 0.2 |

| Not identified | 60 | 13.5 |

| Content | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Brands | 163 | 11.7 |

| Normative body | 172 | 12.3 |

| Healthy foods * | 21 | 1.5 |

| Unhealthy foods * | 18 | 1.3 |

| Health tips * | 31 | 2.2 |

| Swimwear or underwear | 139 | 9.9 |

| Eroticism | 67 | 4.8 |

| Beautiful person | 1 | 0.1 |

| Non-normative body | 17 | 1.2 |

| Family | 52 | 3.7 |

| Pregnancy * | 8 | 0.6 |

| Sport * | 75 | 5.4 |

| Beauty tips | 16 | 1.1 |

| Memes and virals | 10 | 0.7 |

| Bodybuilding | 25 | 1.8 |

| Hospital environment * | 4 | 0.3 |

| Cooking recipes | 12 | 0.9 |

| Other | 429 | 30.7 |

| Content | Female ** | Male ** |

|---|---|---|

| Brands | 90 (12.4%) | 66 (23.2%) |

| Normative body | 140 (19.2%) | 31 (10.9%) |

| Healthy foods * | 11 (1.5%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Unhealthy foods * | 4 (0.5%) | 6 (2.1%) |

| Health tips * | 11 (1.5%) | 12 (4.2%) |

| Swimwear or underwear | 116 (15.9%) | 22 (7.7%) |

| Eroticism | 62 (8.5%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| Beautiful person | 122 (16.8%) | 16 (5.6%) |

| Non-normative body | 16 (2.2%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Family | 40 (5.5%) | 12 (4.2%) |

| Pregnancy * | 8 (1.1%) | 0 |

| Sport * | 45 (6.2%) | 30 (10.6%) |

| Beauty tips | 9 (1.2%) | 3 (1.1%) |

| Memes and virals | 4 (0.5%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| Bodybuilding | 9 (1.2%) | 16 (5.6%) |

| Hospital environment * | 1 (0.1%) | 3 (1.1%) |

| Cooking recipes | 7 (1%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Content | 18–24 ** | 25–34 ** |

|---|---|---|

| Brands | 36 (14.5%) | 105 (15.4%) |

| Normative body | 49 (19.8%) | 102 (15%) |

| Healthy foods * | 3 (1.2%) | 17 (2.5%) |

| Unhealthy foods * | 2 (0.8%) | 16 (2.4%) |

| Health tips * | 2 (0.8%) | 23 (3.4%) |

| Swimwear or underwear | 32 (12.9%) | 91 (13.4%) |

| Eroticism | 10 (4%) | 46 (6.8%) |

| Beautiful person | 42 (16.9%) | 85 (12.5%) |

| Non-normative body | 4 (1.6%) | 11 (1.6%) |

| Family | 13 (5.2%) | 30 (4.4%) |

| Pregnancy * | 2 (0.8%) | 4 (0.6%) |

| Sport * | 11 (4.4%) | 58 (8.5%) |

| Beauty tips | 5 (2%) | 7 (1%) |

| Memes and virals | 2 (0.8%) | 4 (0.6%) |

| Bodybuilding | 2 (0.8%) | 19 (2.8%) |

| Hospital environment * | 0 | 3 (0.4%) |

| Cooking recipes | 2 (0.8%) | 10 (1.5%) |

| Gender (p) | % Females (p) | %Males (p) | Age Range (p) | Type of Content (Dummy) (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (p) | −0.059 (0.079) | 0.059 (0.080) | −0.065 (0.052) | 0.102 (<0.001) | |

| % Females (p) | −1.000 (0.000) | −0.327 (0 < 0.001) | 0.059 (0.073) | ||

| %Males (p) | 0.328 (0 < 0.001) | −0.059 (0.071) | |||

| Age range (p) | 0.120 (<0.001) | ||||

| Type of content |

| Step | Predictor Variable | Rho Spearman | Standardised Coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age range | 0.120 * | 0.119 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Age range | 0.125 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | 0.102 * | 0.101 | 0.003 | |

| Model summary (last step) | ||||

| F | p | R | R2 (R2 adjusted) | |

| 10.88 | <0.001 | 0.156 | 0.024 (0.022) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Picazo-Sánchez, L.; Domínguez-Martín, R.; García-Marín, D. Health Promotion on Instagram: Descriptive–Correlational Study and Predictive Factors of Influencers’ Content. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315817

Picazo-Sánchez L, Domínguez-Martín R, García-Marín D. Health Promotion on Instagram: Descriptive–Correlational Study and Predictive Factors of Influencers’ Content. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315817

Chicago/Turabian StylePicazo-Sánchez, Laura, Rosa Domínguez-Martín, and David García-Marín. 2022. "Health Promotion on Instagram: Descriptive–Correlational Study and Predictive Factors of Influencers’ Content" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315817

APA StylePicazo-Sánchez, L., Domínguez-Martín, R., & García-Marín, D. (2022). Health Promotion on Instagram: Descriptive–Correlational Study and Predictive Factors of Influencers’ Content. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315817