Cyberbullying: Common Predictors to Cyber-Victimisation and Bystanding

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Protection and Risk Factors

1.2. The Role of the Bystander

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

- -

- Outcome variables (X): cyber-victimisation, observation

- -

- Predictors variables (Y): Age, daily frequency of connection, contacts in social networks/messaging, parental mediation-monitoring, parental mediation-co-use, emotional self-regulation-attention to emotions, attitude towards violence as a form of fun, attitude towards violence-improvement of self-esteem, attitude toward violence-management of problems, attitude towards violence considered legitimate.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Cyber-Victimisation and Bystanding

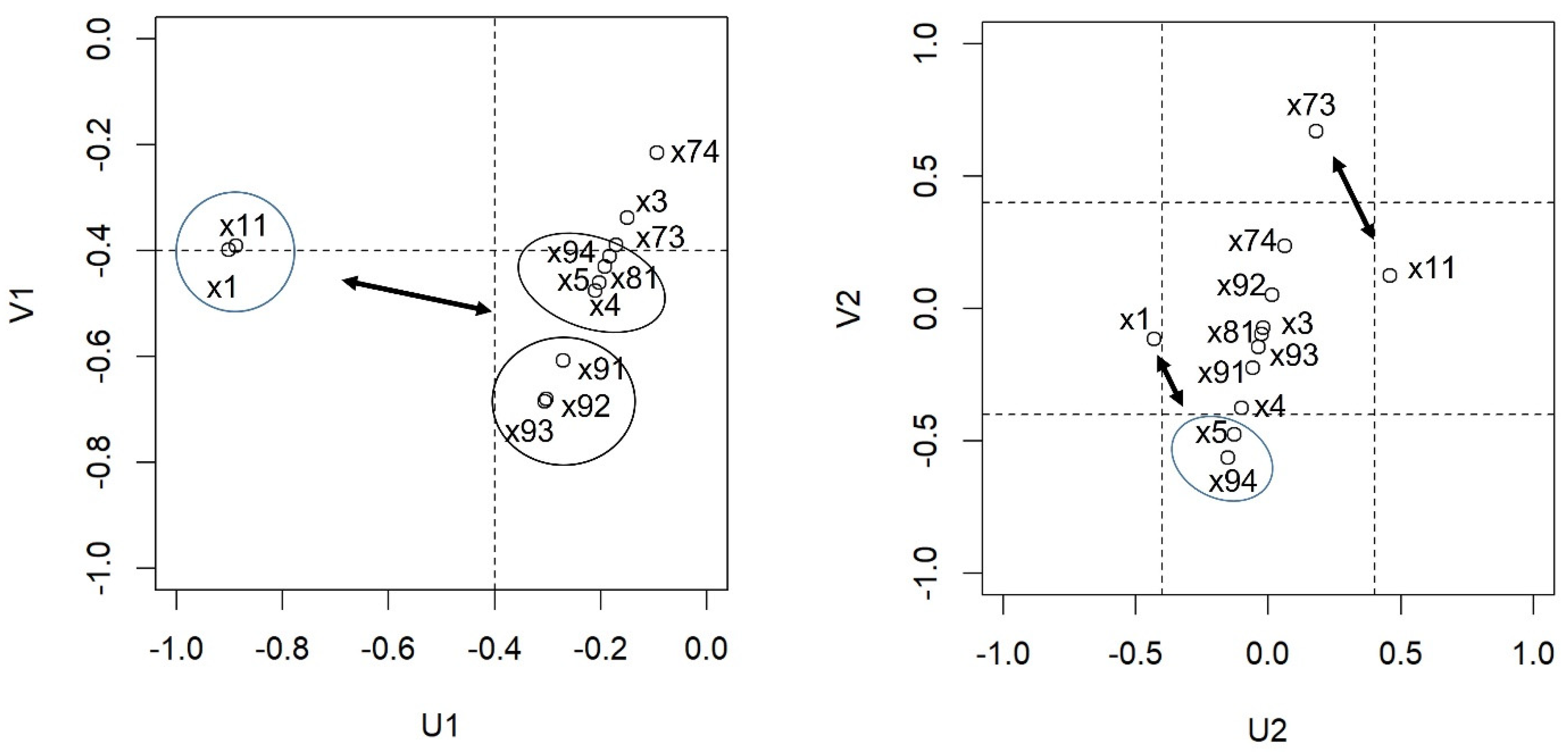

3.2. Canonical Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. Canonical Correlations: Predictors and Relationships

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Lines of Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tokunaga, R.S. Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.J. Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: A comparison of associated youth characteristics. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Aliri, J. Ciberacoso en adolescentes y jóvenes del País Vasco: Diferencias de sexo en víctimas, agresores y observadores. Psicol. Conduct. 2013, 21, 461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, R.; Calmaestra, J.; Mora-Merchán, J.A. Cyberbullying. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2008, 8, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Williford, A.; Boulton, A.; Noland, B.; Little, T.D.; Kärnä, A.; Salmivalli, C. Effects of the KiVa anti-bullying program on adolescents’ depression, anxiety, and perception of peers. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2012, 40, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, P.; Betts, L.; Stiller, J.; Kellezi, B. Bystander responses to cyberbullying: The role of perceived severity, publicity, anonymity, type of cyberbullying, and victim response. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 131, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hamer, A.H.; Konijn, E.A.; Keijer, M.G. Cyberbullying behavior and adolescents’ use of media with antisocial content: A cyclic process model. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlett, C.P.; Gentile, D.A. Attacking others online: The formation of cyber-bullying in late adolescence. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 1, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J.; Gross, E.F. Extending the School Grounds?—Bullying Experiences in Cyberspace. J. Sch. Health 2008, 78, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J. Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behav. 2008, 29, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Huang, S.; Evans, R.; Zhang, W. Cyberbullying Among Adolescents and Children: A Comprehensive Review of the Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Preventive Measures. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 634909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Vidal, L.I.; Epelde-Larrañaga, A.; Chacón-Borrego, F. Predictive Model of The Factors Involved in Cyberbullying of Adolescent Victims. Front. Psychol. 2020, 12, 798926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultze-Krumbholz, A.; Scheithauer, H. Social-behavioral correlates of cyberbullying in a German student sample. Z. Psychol. 2009, 217, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravita, S.C.; Di Blasio, P.; Salmivalli, C. Unique and interactive effects of empathy and social status on involvement in bullying. Soc. Dev. 2009, 18, 140–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglés, C.J.; Torregrosa, M.S.; García-Fernández, J.M.; Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Estévez, E.; Delgado, B. Conducta agresiva e inteligencia emocional en la adolescencia. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 7, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroncelli, A.; Ciucci, E. Unique effects of different components of trait emotional intelligence in traditional bullying and cyberbullying. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Barón, J.; Buelga, S.; Cava, M.J. The Influence of School and Family Environment on Adolescent Victims of Cyberbullying. Comunicar 2016, 46, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C.; Kärnä, A.; Poskiparta, E. Counteracting bulllying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2011, 35, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, E.; Heilman, R.; Hart, K.J. Cyber-bullying: An exploration of bystander behavior and motivation. Cyberpsychology 2014, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machackova, H.; Dedkova, L.; Sevcikova, A.; Cerna, A. Bystanders’ support of cyberbullied schoolmates. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 23, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Martínez-Valderrey, V.; Maganto, C.; Bernarás, E.; Jaureguizar, J. Efectos de Cyberprogram 2.0 en factores del desarrollo socioemocional. Pensam. Psicol. 2016, 14, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Arévalo, B. Los observadores ante el ciberacoso (cyberbullying). Rev. Investig. Esc. 2015, 87, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Fernandez-Tome, A. CCB. Cuestionario de Cyberbullying. FOCAD Formación Continuada a Distancia, 12th ed.; Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Psicólogos: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Perona, V.; Lloret Irles, D. Actitudes y Conductas de Privacidad en Una Muestra de Adolescentes de la Comunitat Valenciana. Un Estudio Exploratorio; Cátedra de Brecha Digital y Buen Uso de las TICs, Universidad Miguel Hernández: Elche, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.A.; Llor, L.; Puebla, T.; Llor, B. Evaluación de las creencias actitudinales hacia la violencia en centros Educativos: El CAHV-25. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2009, 2, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D.P. Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.L.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T.P. Emotional Attention, Clarity, and Repair: Exploring Emotional Intelligence Using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure, & Health; Pennebaker, E.J.W., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, V.; Lloret, D.; Gervilla, J.; Anupol, J. Online risks in adolescence: An exploratory analysis of a Parental Mediation Scale. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference European Society for Prevention Research, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–26 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mardia, K.V.; Kent, J.T.; Bibby, J.M. Multivariate Analysis; Academic Press: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. Applied Multivariate Techniques; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-García, D.; Núñez Pérez, J.C.; Dobarro González, A.; Rodríguez Pérez, C. Factores de riesgo asociados a cibervictimización en la adolescencia. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2015, 15, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. Cyberbullying: An overrated phenomenon? Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 520–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Inteligencia emocional percibida y diferencias individuales en el meta-conocimiento de los estados emocionales: Una revisión de los estudios con el TMMS. Ansiedad Estrés 2005, 11, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gorostiaga, A.; Balluerka, N.; Aritzeta, A.; Haranburu, M.; Alonso-Arbiol, I. Measuring perceived emotional intelligence in adolescent population: Validation of the Short Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-23). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2011, 11, 523–537. [Google Scholar]

- Elipe, P.; Ortega, R.; Hunter, S.C.; del Rey, R. Perceived emotional intelligence and involvement in several kinds of bullying. Psicol. Conduct. 2012, 20, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B.; Darley, J.M. The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help? Appleton-Century-Croft: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg, R.; Tenenbaum, L.; Varjas, J.; Meyers, K.; Jungert, T.; Vanegas, G. Bystander motivation in bullying incidents: To intervene or not to intervene. West J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzoli, T.; Gini, G. Why do bystanders of bullying help or not? A multidimensional model. J. Early Adolesc. 2013, 33, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 47.5 | 266 |

| Male | 52.5 | 294 |

| Age | ||

| 12 | 12.5 | 70 |

| 13 | 54.5 | 305 |

| 14 | 21.4 | 120 |

| 15 | 11.6 | 65 |

| Academic year | ||

| 1 °CSE | 22.5 | 126 |

| 2 °CSE | 77.5 | 434 |

| Frequency of daily connection | ||

| Continuously | 23.4 | 131 |

| 1–2 h/day | 28.0 | 157 |

| 3–4 h/day | 14.1 | 79 |

| 5–6 h/day | 7.0 | 39 |

| Occasionally | 21.4 | 120 |

| No connection | 6.1 | 34 |

| Contacts on social networks/messaging | ||

| No social networks | 3.4 | 19 |

| Less than 10 | 2.5 | 14 |

| 10 and 50 | 16.6 | 93 |

| 50 and 100 | 20.7 | 116 |

| 100 and 300 | 31.6 | 177 |

| Over 300 | 25.2 | 141 |

| Variable | M | DT | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.34 | 0.90 | 12–16 |

| Privacy | |||

| Privacy behaviours | 37.05 | 5.58 | 11–55 |

| Attitudes towards privacy | 31.86 | 4.77 | 9–45 |

| Total scale | 68.91 | 8.16 | 20–100 |

| Parental regulation | |||

| Active regulation | 16.58 | 9.90 | 0–36 |

| Restrictive regulation | 8.16 | 5.36 | 0–20 |

| Parental monitoring | 7.04 | 6.88 | 0–40 |

| Co-use | 6.97 | 3.90 | 0–20 |

| Total scale | 38.74 | 20.72 | 0–116 |

| Emotional self-regulation | |||

| Attention to emotions | 22.07 | 7.83 | 8–40 |

| Emotional clarity and comprehension | 23.79 | 7.23 | 8–40 |

| Emotional regulation and management | 25.77 | 7.76 | 8–40 |

| Attitude towards violence in a school context | |||

| FI: Violence as a form of fun | 13.20 | 5.53 | 7–35 |

| FII: Violence to improve self-esteem | 8.15 | 3.87 | 5–25 |

| FIII: Violence to handle problems and manage relationships | 10.25 | 4.45 | 6–30 |

| FIV: Violence perceived as legitimate | 19.24 | 5.92 | 7–35 |

| Total scale | 50.84 | 17.20 | 25–125 |

| Empathy | |||

| Affective empathy | 13.30 | 4.18 | 4–20 |

| Cognitive empathy | 19.30 | 4.11 | 5–25 |

| Total scale | 32.60 | 7.41 | 9–45 |

| Cyber-Victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item. | Observer | Never | Sometimes | Often-Always | p-Value |

| 1. Have you seen how other have sent offensive and insulting messages via mobile or Internet? | Never | 86.4 (235) | 12.9 (35) | 0.7 (2) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 63.4 (111) | 33.7 (59) | 2.9 (5) | ||

| Often-Always | 36.9 (41) | 44.1 (49) | 18.9 (21) | ||

| 2. Have you seen others making offensive and insulting calls via mobile, Internet, Skype, etc.? | Never | 95 (339) | 4.5 (16) | 0.6 (2) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 75.6 (99) | 22.1 (29) | 2.3 (3) | ||

| Often-Always | 50 (35) | 38.6 (27) | 11.4 (8) | ||

| 3. Have you seen anybody being assaulted or beaten while being recorded and posted on the Internet? | Never | 98 (445) | 1.5 (7) | 0.4 (2) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 83.3 (50) | 15 (9) | 1.7 (1) | ||

| Often-Always | 72.7 (32) | 15.9 (7) | 11.4 (5) | ||

| 4. Have you seen the dissemination of private photos or videos of anybody via mobile or Internet? | Never | 97.1 (299) | 2.3 (7) | 0.6 (2) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 87.6 (149) | 10.6 (18) | 1.8 (3) | ||

| Often-Always | 65 (52) | 18.8 (15) | 16.3 (13) | ||

| 5. Have you seen photos being taken without somebody’s permission to be uploaded on the Internet or spread via phone? | Never | 97.7 (387) | 2 (8) | 0.3 (1) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 81.7 (85) | 16.3 (17) | 1.9 (2) | ||

| Often-Always | 72.4 (42) | 20.7 (12) | 6.9 (4) | ||

| 6. Have you seen anonymous calls being made in order to scare someone or know someone who has received these types of calls? | Never | 90.4 (293) | 7.7 (25) | 1.9 (6) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 66.9 (95) | 26.1 (37) | 7 (10) | ||

| Often-Always | 45.7 (42) | 34.8 (32) | 19.6 (18) | ||

| 7. Have you seen blackmail through calls or messages? | Never | 93.4 (366) | 5.4 (21) | 1.3 (5) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 75.9 (82) | 22.2 (24) | 1.9 (2) | ||

| Often-Always | 58.6 (34) | 20.7 (12) | 20.7 (12) | ||

| 8. Have you seen or know of anyone who has been sexually harassed via mobile or Internet? | Never | 97.3 (436) | 2 (9) | 0.7 (3) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 83.9 (52) | 11.3 (7) | 4.8 (3) | ||

| Often-Always | 60.4 (29) | 14.6 (7) | 25 (12) | ||

| 9. Have you known anybody who comments on other people’s blogs posting defamatory comments, lies, or secrets? | Never | 96.7 (382) | 2 (8) | 1.3 (5) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 87.4 (104) | 11.8 (14) | 0.8 (1) | ||

| Often-Always | 72.7 (32) | 13.6 (6) | 13.6 (6) | ||

| 10. Do you know of anybody who has had their password stolen in order to prevent them from accessing their blog or email? | Never | 95.4 (333) | 3.2 (11) | 1.4 (5) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 89.4 (126) | 8.5 (12) | 2.1 (3) | ||

| Often-Always | 66.2 (45) | 17.6 (12) | 16.2 (11) | ||

| 11 Have you seen edited photos or videos spread through social networks or YouTube to humiliate or laugh at some boy or girl? | Never | 96.4 (375) | 1.8 (7) | 1.8 (7) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 87.5 (98) | 9.8 (11) | 2.7 (3) | ||

| Often-Always | 77.2 (44) | 17.5 (10) | 5.3 (3) | ||

| 12. Have you seen how someone has been harassed in order to try and isolate them from their contacts on social networks? | Never | 96.8 (394) | 2.2 (9) | 1 (4) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 87.1 (88) | 9.9 (10) | 3 (3) | ||

| Often-Always | 50 (25) | 26 (13) | 24 (12) | ||

| 13. Have you seen how someone has been blackmailed into doing something that she/he did not want to do in exchange for not showing their intimate things on the Internet? | Never | 97.5 (423) | 1.8 (8) | 0.7 (3) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 81.4 (70) | 14 (12) | 4.7 (4) | ||

| Often-Always | 63.2 (24) | 21.1 (8) | 15.8 (6) | ||

| 14. Do you know of anybody who has received threats regarding killing them or their family through a mobile phone, social network, or other technology? | Never | 97 (458) | 2.3 (11) | 0.6 (3) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 74.3 (55) | 24.3 (18) | 1.4 (1) | ||

| Often-Always | 66.7 (8) | 16.7 (2) | 16.7 (2) | ||

| 15. Do you know anybody who has been defamed, by people lying on the Internet to sometimes discredit them or spread rumours to hurt them? | Never | 91.7 (311) | 7.1 (24) | 1.2 (4) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes | 77.7 (101) | 19.2 (25) | 3.1 (4) | ||

| Often-Always | 47.2 (42) | 36 (32) | 16.9 (15) | ||

| CV | O | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyber-victimisation (CV) | - | 0.60 * | 0.12 * | 0.14 * | 0.12 * | 0.24 * | 0.11 * | 0.16 * | 0.22 * | 0.28 * | 0.26 * | 0.09 * |

| Observation (O) | - | 0.14 * | 0.23 * | 0.24 * | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.18 * | 0.27 * | 0.27 * | 0.29 * | 0.23 * | |

| Age (1) | - | 0.18 * | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.16 * | 0.13 * | 0.20 * | 0.16 * | ||

| Frequency of daily connection (2) | - | 0.44 * | −0.15 * | 0.02 | 0.19 * | 0.15 * | 0.08 * | 0.12 * | 0.14 * | |||

| Contacts on social network/messaging (3) | - | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.15 * | 0.13 * | 0.09 * | 0.10 * | 0.12 * | ||||

| Parental regulation and monitoring (4) | - | 0.46 * | 0.10 * | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.06 | |||||

| Parental co-use regulation (5) | - | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.03 | ||||||

| Emotional self-regulation-attention to emotions (6) | - | 0.11 * | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Attitude violence–As a form of fun (7) | - | 0.76 * | 0.77 * | 0.62 * | ||||||||

| Attitude violence–improvement of self-esteem (8) | - | 0.79 * | 0.53 * | |||||||||

| Attitude violence–problem management (9) | - | 0.63 * | ||||||||||

| Attitude violence-considered legitimate (10) | - | |||||||||||

| Function | Eigenvalue | % | Canonical Correlation | Wilk’s Lambda | F | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 2 | 0.20 | 72.76 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 8.63 | 20,096 | <0.001 |

| 2 to 2 | 0.07 | 27.24 | 0.27 | 0.93 | 4.79 | 9549 | <0.001 |

| Scales | U1 | U2 |

|---|---|---|

| Cyber-victimisation (X11) | −0.89 | 0.46 |

| Observation (X1) | −0.90 | −0.43 |

| Variables | V1 | V2 |

| Age (X3) | −0.34 | −0.07 |

| Frequency of daily connection (X4) | −0.48 | −0.37 |

| Contacts on social networks/messaging (X5) | −0.46 | −0.48 |

| Parental mediation. Parental monitoring (X73) | −0.39 | 0.67 |

| Parental mediation. Co-use (X74) | −0.22 | 0.24 |

| Emotional self-regulation. Subscale of attention to emotions (X81) | −0.43 | −0.10 |

| Violence. As a form of fun (X91) | −0.61 | −0.22 |

| Violence. Improvement of self-esteem (X92) | −0.68 | 0.05 |

| Violence. Problem management (X93) | −0.68 | −0.15 |

| Violence. Considered legitimate (X94) | −0.41 | −0.56 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lloret-Irles, D.; Cabrera-Perona, V.; Tirado-González, S.; Segura-Heras, J.V. Cyberbullying: Common Predictors to Cyber-Victimisation and Bystanding. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315750

Lloret-Irles D, Cabrera-Perona V, Tirado-González S, Segura-Heras JV. Cyberbullying: Common Predictors to Cyber-Victimisation and Bystanding. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315750

Chicago/Turabian StyleLloret-Irles, Daniel, Víctor Cabrera-Perona, Sonia Tirado-González, and José V. Segura-Heras. 2022. "Cyberbullying: Common Predictors to Cyber-Victimisation and Bystanding" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315750

APA StyleLloret-Irles, D., Cabrera-Perona, V., Tirado-González, S., & Segura-Heras, J. V. (2022). Cyberbullying: Common Predictors to Cyber-Victimisation and Bystanding. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315750