A Mixed-Methods Outcomes Evaluation Protocol for a Co-Produced Psychoeducation Workshop Series on Recovery from Psychosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context of Implementation and Evaluation

2.2. Implementation: Workshop Contents

2.3. Implementation: Broken Crayons Synopsis

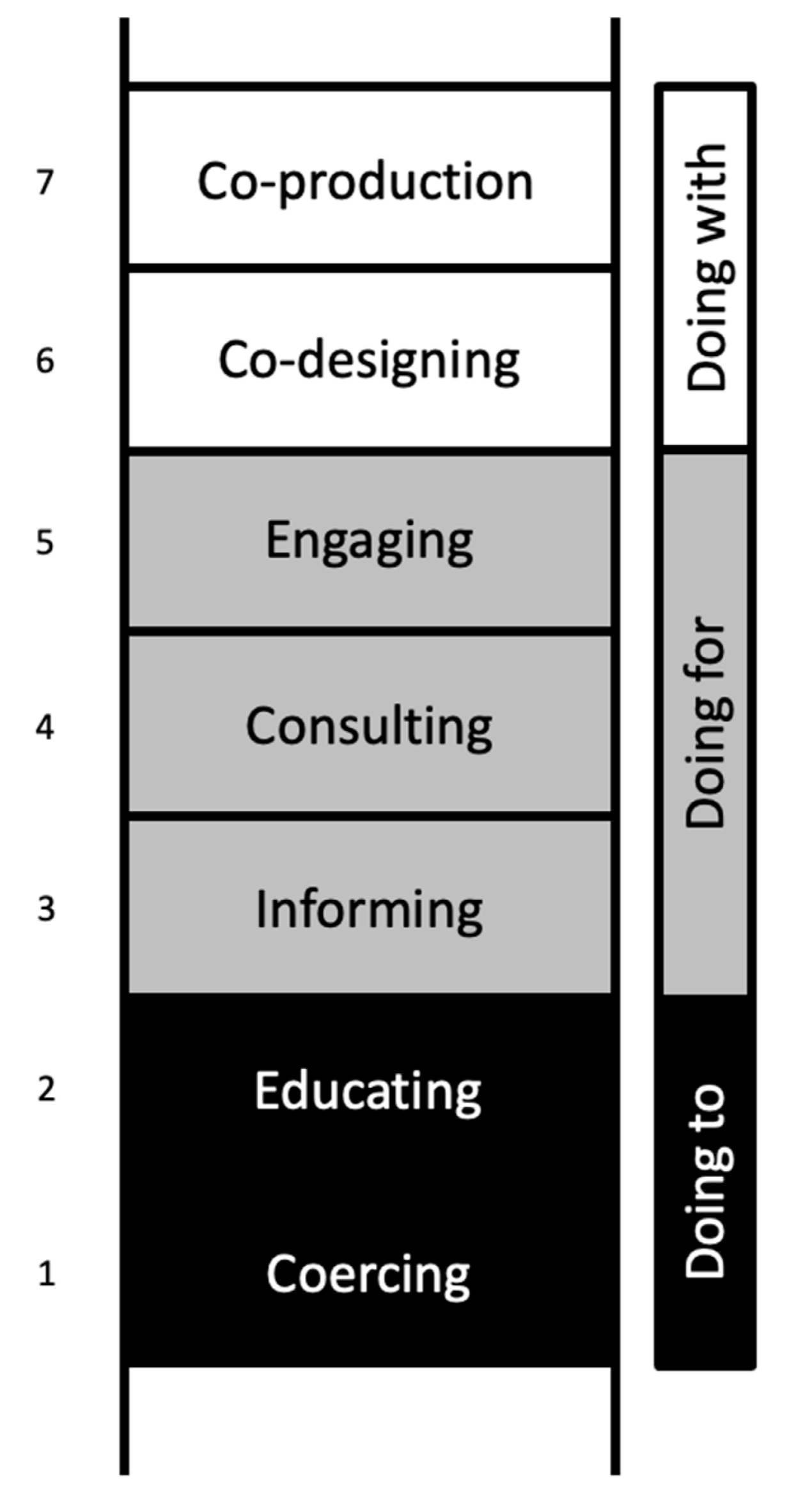

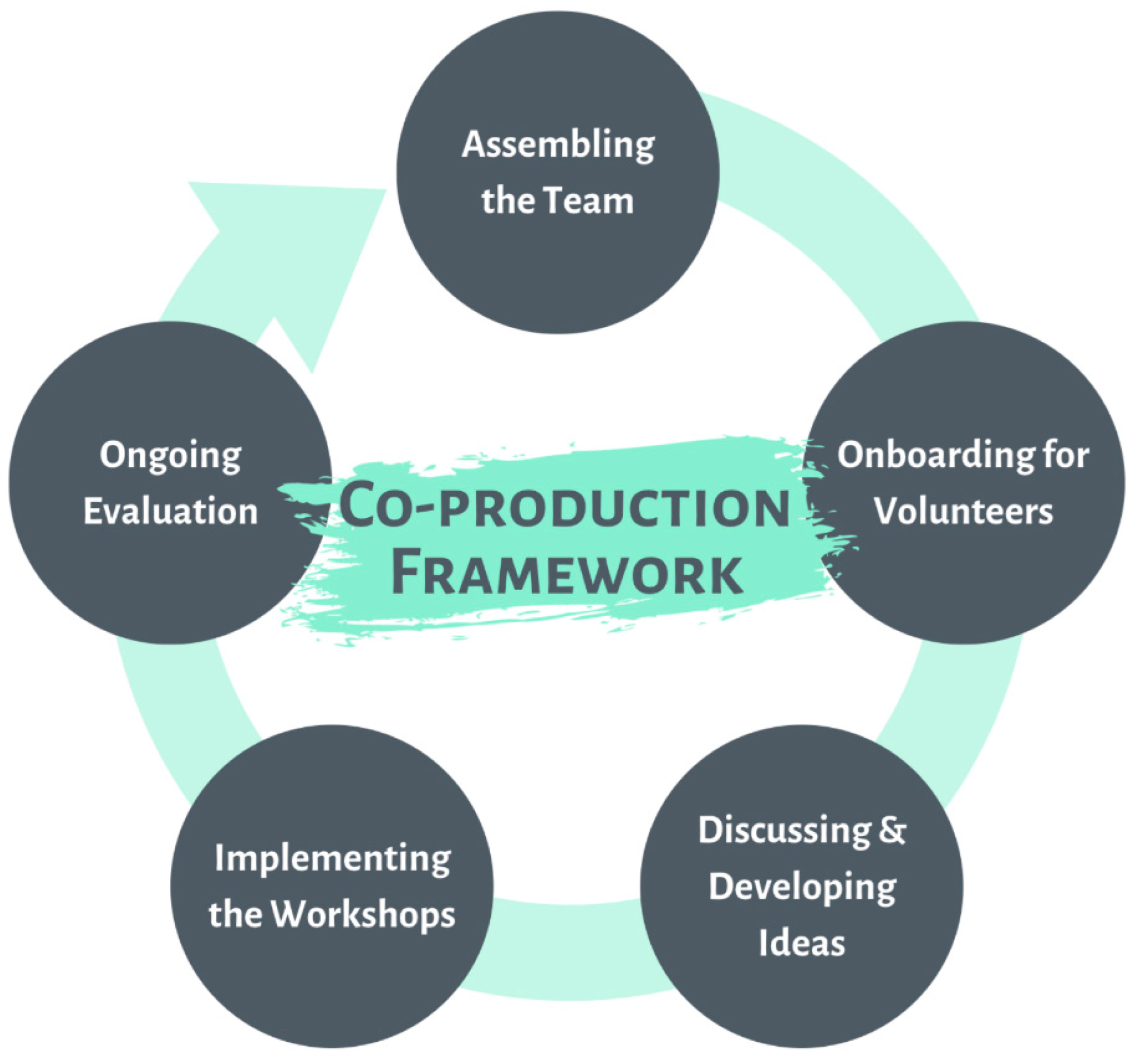

2.4. Implementation: A Framework for Co-Producing Psychoeducation Workshops in EPIP

2.5. Assembling the Team

2.6. On-Boarding of Volunteers (i.e., Team Members Assembled to Form a Team)

2.7. Discussing and Developing Concepts

2.8. Implementation of Workshops

2.9. Ongoing Evaluation

2.10. Evaluation: A Mixed-Methods Outcomes Evaluation Design

2.10.1. Participants

2.10.2. Questionnaire on Process of Recovery

2.10.3. Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS)

2.10.4. Community Integration Measure (CIM)

2.10.5. Social Distance Scale (SDS)

2.10.6. Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS)

2.10.7. Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS)

2.10.8. Patients

2.10.9. Non-Patients

2.10.10. Sample Size Calculation

2.10.11. Data Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, M. Co-production in mental health care. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2015, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, J. The Multiple Facets of Co-Production: Building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, E.S. No More Throw-Away People: The Co-Production Imperative; Essential: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, D.; Harris, M. The Challenge of Co-production. UK: New Economics Foundation. Available online: https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/the-challenge-of-co-production (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. Co-Production: What It Is and How to Do It. Available online: https://www.scie.org.uk/co-production/what-how (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slay, J.; Stephens, L. Co-Production in Mental Health: A Literature Reviewal; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Ang, S.; Tang, C. The Case for Co-production in Singapore’s Mental Healthcare. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 740391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.J. The relationship between social class and mental disorder. J. Primary Prevent. 1996, 17, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Barker, D.; Cowden, F.; Stamps, R.; Yang, M.; Jones, P.B.; Coid, J.W. Psychoses, ethnicity and socio-economic status. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 193, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; DelPozo-Banos, M.; Lloyd, K.; Jones, I.; Walters, J.T.R.; Owen, M.J.; O’Donovan, M.; John, A. Area deprivation, urbanicity, severe mental illness and social drift—A population-based linkage study using routinely collected primary and secondary care data. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 220, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignon, B.; Eaton, S.; Schürhoff, F.; Szöke, A.; McGorry, P.; O’Donoghue, B. Residential social drift in the two years following a first episode of psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 210, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.J.; Shahwan, S.; Goh, C.M.J.; Tan, G.T.H.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. Daily Encounters of Mental Illness Stigma and Individual Strategies to Reduce Stigma—Perspectives of People with Mental Illness. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.T.H.; Shahwan, S.; Goh, C.M.J.; Ong, W.J.; Wei, K.C.; Verma, S.K.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. Mental illness stigma’s reasons and determinants (MISReaD) among Singapore’s lay public—A qualitative inquiry. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Liu, V.; Verma, S. What is life after psychosis like? Stories of three individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Kurokawa, G.; Niimura, J.; Nishida, A.; Shepherd, G.; Yamasaki, S. System-level barriers to personal recovery in mental health: Qualitative analysis of co-productive narrative dialogues between users and professionals. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, R.; Repper, J.; Rinaldi, M.; Brown, H. Recovery Colleges. Nottingham, UK: Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change (ImROC); ImROC: Nottingham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, R.; Meddings, S.; Williams, S.; Repper, J. Recovery Colleges 10 Years On. Nottingham, UK: Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change; ImROC: Nottingham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meddings, S.; Campbell, E.; Guglietti, S.; Lambe, H.; Locks, L.; Byrne, D.; Whittington, A. From Service User to Student—The Benefits of Recovery College. Clin. Psychol. Forum 2015, 268, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Meddings, S.; Byrne, D.; Barnicoat, S.; Campbell, E.; Locks, L. Co-delivered and co-produced: Creating a recovery college in partnership. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2014, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Singapore. DOS|SingStat Website—Populaiton and Population Structure—Latest Data. Available online: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/population/population-and-population-structure/latest-data (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- School of Ability & Recovery. SOAR 2019 Annual Report. Singapore. 2020. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/SOARReport19 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- International Association for Public Participation. Core Values, Ethics, Spectrum—The 3 Pillars of Public Participation. Available online: https://www.iap2.org/page/pillars (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Jones, N. Peer Involvement and Leadership in Early Intervention in Psychosis Services. Available online: https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Peer-Involvement-Guidance_Manual_Final.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Neil, S.T.; Kilbride, M.; Pitt, L.; Nothard, S.; Welford, M.; Sellwood, W.; Morrison, A.P. The questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR): A measurement tool developed in collaboration with service users. Psychosis 2009, 1, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, L.; Kilbride, M.; Nothard, S.; Welford, M.; Morrison, A.P. Researching recovery from psychosis: A user-led project. Psychiatr. Bull. 2007, 31, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Li, Z.; Xie, H.; Tan, B.L.; Lee, J. An Asian study on clinical and psychological factors associated with personal recovery in people with psychosis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 256. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Brown, S.; Tennant, A.; Tennant, R.; Platt, S.; Parkinson, J.; Weich, S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): A Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Ng Fat, L.; Scholes, S.; Boniface, S.; Mindell, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaingankar, J.A.; Abdin, E.; Chong, S.A.; Sambasivam, R.; Seow, E.; Jeyagurunathan, A.; Picco, L.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Subramaniam, M. Psychometric properties of the short Warwick Edinburgh mental well-being scale (SWEMWBS) in service users with schizophrenia, depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McColl, M.A.; Davies, D.; Carlson, P.; Johnston, J.; Minnes, P. The community integration measure: Development and preliminary validation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 82, 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C.; Bresnahan, M.; Stueve, A.; Pescosolido, B.A. Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, S.R.; Fiszbein, A.; Opler, L.A. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Saraswat, N.; Rao, K.; Subbakrishna, D.K.; Gangadhar, B.N. The Social Occupational Functioning Scale (SOFS): A brief measure of functional status in persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 81, 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, S.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Faul, F. A short tutorial of GPower. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, M. Impact of Subject Attrition on Sample Size Determinations for Longitudinal Cluster Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2014, 24, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.; King, M.; Russell, J. A mixed-methods evaluation of a Recovery College in South East Essex for people with mental health difficulties. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- IBM. Release Notes-IBM SPSS Statistics 23. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/release-notes-ibm-spss-statistics-23 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, Y. This Is What Inequality Looks Like: Essays; Ethos Books: Singapore, 2018; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M.; McDaid, D.; Shepherd, G.; Williams, S.; Repper, J. Recovery: The Business Case; ImROC: Nottingham, UK, 2017. Available online: https://www.researchintorecovery.com/files/2017%20ImROC%2014%20Recovery%20Business%20Case.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Yeoh, G. The Rise of Mental Health Awareness—And the Stigma that Remains Attached to Certain Conditions-CNA. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/singapore-mental-health-awareness-stigma-conditions-depression-1973166?fireglass_rsn=true#fireglass_params&tabid=ade8c020add41822&start_with_session_counter=3&application_server_address=ihispteltd9-asia-southeast1.prod.fire.glass (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Bourne, P.; Meddings, S.; Whittington, A. An evaluation of service use outcomes in a Recovery College. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Session | Activities |

|---|---|

| 1 | Workshop 1: Understanding Psychosis A psychiatrist will be giving a talk on the biological aspects of psychosis for the purpose of psychoeducation. A person in recovery will be sharing his or her recovery story toward the end of the session too. An opportunity for Q&A will be available to participants. |

| 2 and 3 | Workshops 2 and 3: Journeying with Psychosis 1 and 2 Various everyday aspects of living with a psychotic illness (issues of medications, dealing with negative mindsets, and understanding a mind in a psychotic episode) will be covered in these workshops. More persons with a lived experience of psychosis will be invited to share their stories of recovery with the participants in creative and interactive ways. |

| 4 | Workshop 4: What keeps you going? This workshop will address negative symptoms of psychotic disorders to help participants find internal motivations to keep going while living with psychosis. |

| 5 | Workshop 5: Disclosure of Medical History This workshop will happen in the form of a panel discussion, where employers, caregivers, persons in recovery, and a moderator will come together and have a structured discussion about disclosure of medical history in mental health issues. |

| 6 | Workshop 6: Family & Friends This final session is a wrap-up of the workshop series, where participants will learn more about practicing gratitude and could show gratitude toward their supporters in their journeys. |

| S/N | Self-Assessment Questions for Meaningful Peer Involvement (Jones, 2016) [24] | Self-Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Have attempts been made to include peers as early as possible in planning a new initiative or program? | Yes. Peers were involved right from the beginning of the creation of broken crayons workshops. |

| 2 | Do peers have the power to make decisions and shape the programs, or are they limited to “advisory” roles? | Yes. Peers were given the power to make executive decisions about broken crayons, a democratic approach is usually taken to resolve differences. |

| 3 | Are peers financially compensated in a manner equal to non-peers? | Yes. We hired a research executive who has a lived experience to helm the program. She was compensated based on her educational qualifications and work experience. Her salary and job grade were determined using industry standards by our HR department. |

| 4 | Is there critical mass (or sufficient number) of peers involved to make a difference? | We have a thriving group of peers and caregivers volunteering in our midst to design and deliver broken crayons. Mental health professionals are in minority numbers in our volunteer group. |

| 5 | Have steps been taken to ensure that peer wellness is prioritized? | Yes, psychological safety and alliance was built between peers and peer staff to ensure that peers are well supported. |

| 6 | Has the program or organization invested in peer capacity building—e.g., paying peers to attend conferences and workshops and to learn new skills? | Yes, peer capacity building is a priority, where peers were given volunteers training and informal qualitative feedback after every workshop for continuous learning and development. |

| 7 | Have program leaders or administrators taken explicit steps to ensure that peer perspectives are valued, and that resistance to peer involvement is systematically addressed? | Program leaders have made it clear that peer involvement is the mainstay of the program and encouraged peer involvement in meaningful ways. |

| Step | Activities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Volunteer induction | ||

| Low involvement | Medium involvement | High involvement | |

| Go through a checklist of do’s and don’ts with the volunteers | Group 2 newcomers with 1 more experienced volunteer to learn the ropes (1:3 or 1:4 ratio) Mentor/mentee | Tag each newcomer with a more experienced volunteer to learn the ropes Welcome people in different stages of recovery as they are | |

| 2 | Volunteer roles | ||

| Low involvement | Medium involvement | High involvement | |

| Assign fixed roles to volunteers E.g., Timekeeper, graphic design (posters), scribers | Discuss potential roles with volunteers E.g., Facilitator, curriculum developer | Share about the program Ask volunteers to contribute based on their strengths and interests Working with volunteers in whatever stage of recovery they are at | |

| 3 | Stage-by-stage involvement | ||

| Low involvement | Medium involvement | High involvement | |

| Sitting in a session Experience a co-produced workshop or planning discussion Help with scribing | Facilitate a small segment of the workshop Icebreaker Small group facilitation Involve in a bit of planning | Take the lead in session Plan Be main facilitator Full on practical | |

| 4 | Development and retention | ||

| Low involvement | Medium involvement | High involvement | |

| Little or no development of volunteers E.g., group debrief | Some development or training of volunteers E.g., Role-playing and “comparing notes” within the facilitators during dry run, newer facilitators being tagged to EPIP team members (e.g., a more experienced facilitator is tagged with a less experienced facilitator in a breakout room) | Long-term development plans and training and development of volunteers based on their strengths and skills | |

| 5 | Commitment level | ||

| Low involvement | Medium involvement | High involvement | |

| No flexibility E.g., Timings are catered to organizer’s schedule and preferences. | Some flexibility E.g., offering suggestions to volunteers for session timings (e.g., give two dates), discuss possible timings together. | Catered to the volunteers’ schedule and commitments E.g., Having a contingency plan for volunteers should they have other work or last-minute commitments to attend to and cannot be there for the workshop. | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.Y.; Koo, W.L.; Tan, Y.F.; Seet, V.; Subramaniam, M.; Ang, S.; Tang, C. A Mixed-Methods Outcomes Evaluation Protocol for a Co-Produced Psychoeducation Workshop Series on Recovery from Psychosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315464

Lee YY, Koo WL, Tan YF, Seet V, Subramaniam M, Ang S, Tang C. A Mixed-Methods Outcomes Evaluation Protocol for a Co-Produced Psychoeducation Workshop Series on Recovery from Psychosis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315464

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ying Ying, Wei Ler Koo, Yi Fong Tan, Vanessa Seet, Mythily Subramaniam, Suying Ang, and Charmaine Tang. 2022. "A Mixed-Methods Outcomes Evaluation Protocol for a Co-Produced Psychoeducation Workshop Series on Recovery from Psychosis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315464

APA StyleLee, Y. Y., Koo, W. L., Tan, Y. F., Seet, V., Subramaniam, M., Ang, S., & Tang, C. (2022). A Mixed-Methods Outcomes Evaluation Protocol for a Co-Produced Psychoeducation Workshop Series on Recovery from Psychosis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315464