A Systematic Review of Scientific Studies on the Effects of Music in People with Personality Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Personality Disorders

1.2. Music Preferences, and Music Perception in PDs

1.3. Music Therapy and PDs

1.4. Aims and Objectives

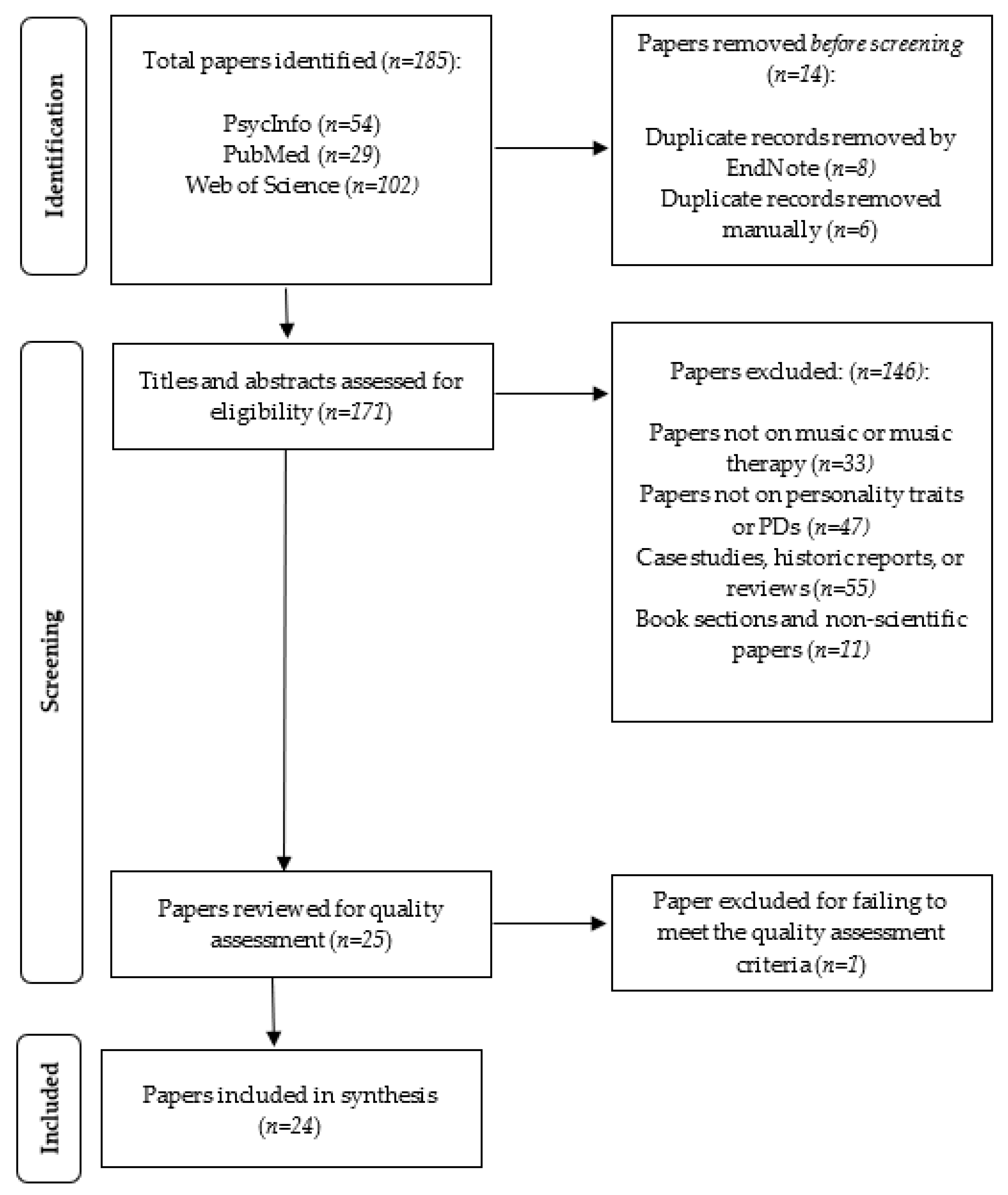

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies were published in English or had an English-language abstract.

- Studies were original.

- Study participants were diagnosed with, or had symptoms related to, a PD.

- Study participants were asked about music; music or MT was used as an intervention; or participants experienced music-related symptoms.

- Animal studies.

- Studies using only unoriginal data.

- Case studies, conference articles, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses.

- Studies that did not report results or clinical outcomes.

- Studies on dance or art therapy that did not report a specific result for MT.

- Studies where music was not linked to PDs or related personality traits.

- Studies where the results for participants with PDs or traits related to PDs were not reported separately.

- Studies that examined only a particular piece of music, composer, or performer.

2.3. Screening, Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Studies Looking at Music Preference in People with PDs or Personality Traits Associated with PDs

3.1.1. Studies Looking at Music Preferences in People with PDs

3.1.2. Studies Looking at Music Preferences in People with Personality Traits Associated with PDs

3.2. Studies Looking at MT for People with PDs or Personality Traits Associated with PDs

3.2.1. Studies Looking at MT for People with PDs

3.2.2. Studies Looking at MT for People with Traits Associated with PDs

3.3. Studies Looking at Music Performance in People with Personality Traits Associated with PDs

3.4. Studies Looking at Music Imagery in People with Personality Traits Associated with PDs

4. Discussion

4.1. Methods and Content of Included Studies

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Personality Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 645–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.W.; Gunderson, J.; Mulder, R. Treatment of Personality Disorder. Lancet 2015, 385, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høye, A.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Bramness, J.G.; Nesvåg, R.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Heiberg, I. Total and cause-specific mortality in patients with personality disorders: The association between comorbid severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasalova, P.; Prasko, J.; Kantor, K.; Zatkova, M.; Holubova, M.; Sedlackova, Z.; Slepecky, M.; Grambal, A. Personality disorder in marriage and partnership—A narrative review. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2018, 39, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Personality Disorders: Borderline and Antisocial. Quality Standard [QS88]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs88 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Stoffers-Winterling, J.M.; Völlm, B.A.; Rücker, G.; Timmer, A.; Huband, N.; Lieb, K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 8, CD005652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antisocial Personality Disorder: Prevention and Management. Clinical Guidelines [CG77]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg77/chapter/1-Guidance#treatment-and-management-of-antisocial-personality-disorder-and-related-and-comorbid-disorders (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Watts, J. Problems with the ICD-11 classification of personality disorder. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, S.; Brunero, S. Personality disorder prevalence and treatment outcomes: A literature review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 30, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Fan, H.; Shen, C.; Wang, W. Genetic and neuroimaging features of personality disorders: State of the art. Neurosci. Bull. 2016, 32, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, B.; Dowling, M. Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Psychitr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 21, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempértegui, G.A.; Karreman, A.; Arntz, A.; Bekker, M.H. Schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: A comprehensive review of its empirical foundations, effectiveness and implementation possibilities. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Borderline Personality Disorder: Treatment and Management. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55403/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Newton-Howes, G.; Clark, L.A.; Chanen, A. Personality disorder across the life course. Lancet 2015, 21, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentfrow, P.J.; Gosling, S.D. Message in a ballad: The role of music preferences in interpersonal perception. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, A.; Olsen, K.N.; Thompson, W.F. An investigation of empathy in male and female fans of aggressive music. Music Sci. 2019, 25, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehlow, G.; Lindner, R. Music therapy interaction patterns in relation to borderline personality disorder (BPD) patients. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2016, 25, 134–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenner, J.; Baker, F.A.; Treloyn, S. Perspectives on musical competence for people with borderline personality disorder in group music therapy. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2020, 29, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Agius, M. The Use of Music Therapy in the Treatment of Mental Illness and the Enhancement of Societal Wellbeing. Psychiatr. Danub. 2018, 30, 595–600. Available online: https://www.psychiatria-danubina.com/UserDocsImages/pdf/dnb_vol30_noSuppl%207/dnb_vol30_noSuppl%207_595.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Kemper, K.J.; Danhauer, S.C. Music as Therapy. South Med. J. 2005, 98, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geretsegger, M.; Mössler, K.A.; Bieleninik, Ł.; Chen, X.J.; Heldal, T.O.; Gold, C. Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 5, CD004025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geretsegger, M.; Elefant, C.; Mössler, K.A.; Gold, C. Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 6, CD004381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.P.A.; Applewhite, B.; Heiderscheit, A.; Himmerich, H. A Systematic Review of Scientific Studies and Case Reports on Music and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, Z.C.; Lace, W.; Coleman, T.R.; Roth, R.M. Challenging the presumptive link between musical preference and aggression. Psychol. Music 2021, 49, 1515–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Health Service. Treatment—Borderline Personality Disorder. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/borderline-personality-disorder/treatment/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Gebhardt, S.; Dammann, I.; Loescher, K.; Wehmeier, P.M.; Vedder, H.; von Georgi, R. The effects of music therapy on the interaction of the self and emotions—An interim analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 41, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odell-Miller, H. The Practice of Music Therapy for Adults with Mental Health Problems: The Relationship between Diagnosis and Clinical Method. Ph.D. Thesis, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 2007. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/316445432/odell_miller.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Hereld, D.C. Music as a regulator of emotion: Three case studies. Music Med. 2019, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, J.; Odell-Miller, H. Aggression in music therapy and its role in creativity with reference to personality disorder. Arts Psychother. 2011, 38, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2020, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.D.; Quatman, C.E.; Manring, M.; Siston, R.A.; Flanigan, D.C. How to write a systematic review. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013, 42, 2761–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI Global. Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Plitt, H. Becoming aware of implicit relational knowledge in music therapy. Musikther. Umschau. 2014, 35, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.J.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N. Guidance on narrative synthesis—An overview, and Applying the guidance 1: Effectiveness studies. In Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews; Version 1, ESRC Methods Programme; University of Lancaster: Lancaster, UK; Available online: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Gebhardt, S.; Kunkel, M.; von Georgi, R. Emotion modulation in psychiatric patients through music. Music Percept. 2014, 31, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garralda, M.E.; Connell, J.; Taylor, D.C. Peripheral psychophysiological reactivity to mental tasks in children with psychiatric disorders. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1990, 240, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, S.M.; Watts, A.L.; Costello, T.H.; Murphy, B.A.; Lilienfeld, S.O. Psychopathy and entertainment preferences: Clarifying the role of abnormal and normal personality in music and movie interests. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 129, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, N.G.; South, S.C.; Oltmanns, T.F. Attentional coping style obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: A test of the intolerance of uncertainty hypothesis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerra, G.; Zaimovic, A.; Franchini, D.; Palladino, M.; Giucastro, G.; Reali, N. Neuroendocrine responses of healthy volunteers to ‘techno-music’: Relationships with personality traits and emotional state. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1998, 28, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, M.E.; Damasio, A.; Habibi, A. Unique personality profiles predict when and why sad music is enjoyed. Psychol. Music. 2021, 49, 1145–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, K.D.; Fouts, G.T. Music preferences, personality style, and developmental issues of adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivathasan, S.; Philibert-Lignieres, G.; Quintin, E.M. Individual Differences in Autism Traits, Personality, and Emotional Responsiveness to Music in the General Population. Music Sci. 2021, 26, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwalek, C.M.; McKinney, C.H. The use of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) in music therapy: A sequential explanatory study. J. Music Ther. 2015, 52, 282–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foubert, K.; Collins, T.; De Backer, J. Impaired maintenance of interpersonal synchronization in musical improvisations of patients with borderline personality disorder. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foubert, K.; Sebreghts, B.; Sutton, J.; De Backer, J. Musical encounters on the borderline. Patterns of mutuality in musical improvisations with borderline personality disorder. Arts Psychother. 2020, 67, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannibal, N.; Pedersen, I.N.; Hestbæk, T.; Sørensen, T.E.; Munk-Jørgensen, P. Schizophrenia and personality disorder patients’ adherence to music therapy. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2012, 66, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.E.; Love, C.C. Total quality management and the reduction of inpatient violence and costs in a forensic psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr. Serv. 1996, 47, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montello, L.; Coons, E.E. Effects of active versus passive group music therapy on preadolescents with emotional, learning, and behavioral disorders. J. Music Ther. 1998, 35, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, N.; Rotem, T.; Arnon, Z.; Haimov, I. The Effect of Music Relaxation versus Progressive Muscular Relaxation on Insomnia in Older People and Their Relationship to Personality Traits. J. Music Ther. 2008, 45, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E. The relationship between small music ensemble experience and empathy skill: A survey study. Psychol. Music. 2021, 49, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullensiefen, D.; Fry, J.; Jones, R.; Jilka, S.; Stewart, L.; Williamson, V.J. Individual differences predict patterns in spontaneous involuntary musical imagery. Music Percept. 2014, 31, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, K.; Sekiguchi, T. Individual traits that influence the frequency and emotional characteristics of involuntary musical imagery: An experience sampling study. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, T.; Mehlhorn, C. Can personality traits predict musical style preferences? A meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppers, D.; Van, H.; Peen, J.; Alberts, J.; Dekker, J. The influence of depressive symptoms on the effectiveness of a short-term group form of Schema Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for personality disorders: A naturalistic study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M. The musical field. Cult Trends. 2006, 15, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuust, P.; Heggli, O.A.; Friston, K.J.; Kringelbach, M.L. Music in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 23, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doak, B.A. Relationships between adolescent psychiatric diagnoses, music preferences and drug preferences. Music Therapy Perspect. 2003, 21, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, K.; Eerola, T. How listening to music and engagement with other media provide a sense of belonging: An exploratory study of social surrogacy. Psychol. Music 2020, 48, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, K.; Saarikallio, S.; Eerola, T. Music may reduce loneliness and act as a social surrogate for a friend: Evidence from an experimental listening study. Music Sci. 2020, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFerran, K.S.; Saarikallio, S. Depending on music to make me feel better: Who is responsible for the ways young people appropriate music for health benefits. Arts Psychother. 2013, 41, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.; Carpenter, J.; Burns, D. Reporting guidelines for music-based interventions. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 2, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Country | Sample and Group Size (n) | Total N | Age Range | Mean Age | Study Design | Questionnaires and Research Methods | Types of Treatment | Main Outcomes | Statistical Significance of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Studies looking at music preferences of people with PDs or personality traits associated with PDs | ||||||||||

| (1.1.) Studies looking at music preferences of people with PDs | ||||||||||

| Gebhardt et al. (2014) [35] | Germany | Psychiatric patients (n = 180): Females (n = 103); Males (n = 77). Healthy controls (n = 430). | 610 | 18–82 | 34.6 | Cross-sectional. Participants completed questionnaires to determine use of music in everyday life. Results from questionnaires analysed against reference sample. | GAF, IAAM | N/A | Patients with PDs used music mainly for cognitive problem solving and the reduction of negative activation. | T2-Hotelling (within analysis): F6 (p < 0.001). Reduction of negative activation: MANOVA ONEWAY (p < 0.001); cognitive problem solving MANOVA ONEWAY (p < 0.001). |

| (1.2.) Studies looking at music preferences of people with personality traits associated with PDs | ||||||||||

| Garralda et al. (1990) [36] | UK | Children attending child psychiatric unit with emotional or conduct disorder: Females (n = 8); Males (n = 7). Clinical conduct disorder (n = 9); Emotional disorder (n = 6). High neurotic tendencies Group (n = 6); high antisocial tendencies Group (n = 4). | 15 | N/A | N/A | Cross-sectional. Participants’ skin conductance and heart rate changes were measured while given mental imagery tasks and while listening to music. Results were compared by diagnosis and symptom type. | RBTQ | N/A | Listening to either soft or rock music had no statistically significant difference between the groups’ cardiovascular and skin conductance reactivity. | N/A |

| Bowes et al. (2018) [37] | United States | North American community members: Females (46%); Males (54%). | 429 | N/A | 36.53 | Cross-sectional. Participants completed surveys to determine personality traits and entertainment preferences. | PRI-R, LSRP, NPI, Mach-IV, HEXACO PI-R | N/A | Openness to experience showed a moderate association with a preference for blues and jazz music and a weak association with rock and alternative music. | Association between openness and blues and jazz (p < 0.001); between openness and rock and alternative (p < 0.001). |

| Gallagher et al. (2003) [38] | United States | Undergraduate psychology students: Females (67%); Males (33%). Obsessive Compulsive (OC) group (n = 60); Normal Control (NC) group (n = 60); Avoidant personality (AV) group (n = 40). | 160 | N/A | 18.9 | Cross-sectional. Participants sorted into OC, AV, and NC groups. Groups given cognitive ability test and factors associated with information seeking/avoidance were measured and analysed. | MR Test, OCPD DS, PDQ-4, SNAP | N/A | Participants in OC group spent less time listening to music prior to taking a stressful test compared to AV and NC groups. | Results of Fisher’s LSD comparing OC, AV, and NC groups’ time spent listening to music (p < 0.01) |

| Gerra et al. (1998) [39] | Italy | Psychosomatically healthy high school students: Females (n = 8); Males (n = 8). | 16 | N/A | Median: 18.6 | Cross-sectional. Participants exposed to techno or classical music and changes in emotional state were measured in basal conditions and after the music exposure. | BDHI, CS, NMAC, TPQ, VZ | N/A | Novelty-seeking personality trait moderately negatively correlated with the von Zerssen score (indicating a reduced negative effect) when listening to techno music. | Association between novelty-seeking and von Zerssen Δ scores (p < 0.05) |

| Merz et al. (2021) [24] | United States | US residents recruited through online crowdsourcing platform: Females (50.3%); Males (49%). | 400 | 18–77 | 34.14 | Cross-sectional. Participants given questionnaires to assess music preference and aggression. | AGQ; DSM-V CCSM, RPQ, STOMP-R, NOBAGS | N/A | Preference for intense music genres (alternative, rock, punk, and heavy metal) was a nonsignificant predictor of aggression. | N/A |

| Sachs et al. (2021) [40] | United States | Recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (n = 218): undergraduates at US University (n = 213). Females (n = 431). | 431 | N/A | 27.05 | Cross-sectional. Participants given access to survey with questions presented randomly. | GEMS, IRI, RRQ, TAS, 10-IPI | N/A | Rumination was associated with liking sad music but not in positive situations (e.g., at a celebratory event). Being conscientious, emotional stability, and empathic concern were all significantly negatively correlated with using sad music in positive situations while openness to experience positively correlated with this. | Positive association between rumination and sublime feelings (p = 0.04); between openness to experience and “positive other” (p = 0.04). Negative associations between “positive other” and conscientiousness (p = 0.04); emotional stability (p = 0.03); and rumination (p < 0.001). |

| Schwartz and Fouts (2003) [41] | Canada | Junior and senior high school students: Females (n = 92); Males (n = 72). | 164 | 12–19 | 16 | Cross-sectional. Participants given survey to complete determining preferences for musical qualities as one of three types (heavy, light, or eclectic); music preferences were compared to each other and against measures of personality. | MAPI | N/A | Those preferring heavy music qualities were significantly more assertive in their relationships and significantly less concerned about the feelings and reactions of others. They were significantly more moody, pessimistic, sensitive, discontented, impulsive, and disrespectful to others and society. | Association between heavy music qualities and assertiveness (p < 0.001), social tolerance (p < 0.01), sensitivity (p < 0.01), and impulse control (p < 0.001). (All when compared to association between preference for light and eclectic music qualities.) |

| Sivathasan et al. (2021) [42] | Canada | Participants recruited through university and online: Females (n = 74); Males (n = 36). | 110 | 18–35 | 21.25 | Cross-sectional. Participants given surveys investigating music preferences, personality traits, and traits related to autism. | AQ, Gold-MSI-Emotion, NEO-FFI-3 (Short), SRS-SCI, SRS-2, | N/A | People with fewer autistic traits and higher levels of extraversion reported greater emotional responsiveness to music. | Association between SRS-2 and extraversion (p < 0.001); between NEO-E and Gold-MSI-Emotion (p < 0.01) |

| (2) Studies looking at MT for people with PDs or personality traits associated with PDs | ||||||||||

| (2.1.) Studies looking at MT for people with PDs | ||||||||||

| Chwalek and McKinney (2015) [43] | United States | Music therapists working in mental healthcare settings: Females (n = 41); Males (n = 6). DBT music therapists (n = 18); non-DBT therapists (n = 29). | 47 + 2 music therapists recruited for qualitative interviews | 23–64 | 39.3 | Two-phase mixed methods design to evaluate the use of DBT in MT. The first phase was a quantitative online survey; the second phase was a qualitative interview. | Assessment of DBT practices | N/A | 38.3% of music therapists used components of DBT in their MT practice. Most DBT music therapists used DBT with individuals with BPD, mostly to address patients’ mindfulness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance. Few music therapists used DBT to address interpersonal effectiveness. | N/A |

| Foubert et al. (2017) [44] | Belgium | Psychiatric hospital patients with BPD (n = 16): Females (n = 12); Males (n = 3); Transgender (n = 1). Healthy controls from the community: (n = 12). | 28 | 21–51 | 31 | Case-control. Participants in BPD and control groups undertook MT, and their improvisations were recorded. Data analysed musically and statistically and summarised by participants’ playing style. | APD-IV, DID, ECR-R, Gold-MSI, SCID II; assessed music training/understanding. | Improvisation-based MT session using ABA structures. | In the freer improvisational section, participants with BPD did not show musical synchronicity (playing in time) compared to healthy controls. | Differences in temporal lag in section B1 between BPD participants and controls (p = 0.029). |

| Foubert et al. (2020) [45] | Belgium | Psychiatric hospital patients with BPD: Females (n = 15); Males (n = 5). | 20 | 21–51 | 33 | Qualitative. Participants given MT session. The principal researcher observed the improvisations and coded the data into six themes of distorted music playing. | SCID-II | Improvisation-based MT session using ABA structure. | Patients with BPD showed distorted patterns of music improvisation. | N/A |

| Gebhardt et al. (2018) [26] | Germany | Inpatients in psychiatric wards (PDs = 3%): Females (n = 85). MT Group (n = 82); non-MT Group (n = 55). | 137 | 18–66 | 40.5 | Cross-sectional. Participants split into MT and non-MT groups. Participants’ personality traits and use of music were measured, analysed, and compared across groups. | IAAM, SKI | Group MT: 60–85 min/once a week. (Number of sessions for participants ranged from 1–9.) | In the MT Group, insecurity predicted the use of music for cognitive problem solving and fun. | Association between reduced ego-strength and cognitive problem solving (p = 0.015) and fun-seeking through music (p = 0.025). |

| Hannibal et al. (2012) [46] | Denmark | Psychiatric patients with either schizophrenia (n = 10) or PD diagnosis (n = 17): Females (n = 15), Males (n = 12). | 27 | 19–59 | 30 | Naturalistic follow-up study measuring patients’ adherence to MT. ‘Adherence’ was defined as doing MT for longer than agreed upon. | N/A | MT: time and length of sessions varied between Participants. | Patients with PDs mostly adhered to MT (87%). None of the variables significantly predicted rates of adherence. | N/A |

| Kenner et al. (2020) [18] | Australia | Female outpatients of private psychiatric hospital with diagnosed BPD or traits of BPD and who had previously received DBT (n = 7). | 7 | 25–60 | N/A | Emergent methods qualitative study. MT sessions were filmed and then analysed. Music competency was established by authors. | N/A | MT: 75 min/once a week for 8 weeks. | Participants’ changing attitudes towards MT included increased confidence in sessions and more rhythmic synchronicity in group improvisation. Perceiving oneself as competent at group improvisation appeared useful for the broader goal of relational efficacy. | N/A |

| Plitt (2014) [33] | Germany | Female inpatients at psychosomatic clinic for women with BPD (n = 10). | 10 | N/A | 28.5 | Qualitative. MT sessions featuring improvisations and patient/therapist conversations. Improvisations and conversations were recorded and then analysed. | N/A | MT session featuring improvisations (average length 5:01 min) and conversations (average length 30:02 min). | Subjective conclusion that intersubjectivity (awareness of others and awareness of a shared experience) in MT is especially important for people with BPD. | N/A |

| Pool and Odell-Miller (2011) [29] | UK | Music therapists (n = 3); male patient with PDs included in case study (n = 1). | 3 music therapists + 1 patient | N/A | N/A | Qualitative mixed-methods design. Single patient case study then thematic analysis of interviews with music therapists. | N/A | For case study– MT: 50 min/once a week for 10 weeks. | Subjective conclusion that aggression and creativity share important similarities in areas of control, affect, and emotion. MT can provide a context for safe exploration of aggression and other complex emotions. | N/A |

| Strehlow and Lindner (2016) [17] | Germany | Women who had been hospitalised by court order because of suicide attempts or suicidal tendencies: (n = 20) | 20 | 19–45 | (n = 12) < age 25 | Systematic qualitative. MT sessions recorded, and scenes analysed and compared to each other. Four categories established to provide a framework to analyse scenes. | N/A | MT: 30 min/twice a week (sessions across participants ranged from 12–150). | 10 themes identified as characteristic of typical BPD interactions in MT. | N/A |

| (2.2.) Studies looking at MT for people with personality traits associated with PDs | ||||||||||

| Hunter and Love (1996) [47] | United States | Male inpatients at maximum security state psychiatric hospital: mentally disordered parolees (28%); mentally ill inmates (40%); patients incompetent to stand trial (12%); not guilty by reason of insanity (14%); other types of forensic and civil commitments (6%). | c. 1000 | N/A | N/A | Case series. Changes implemented in hospital based on TQM methods and checked a year later if these methods had reduced mealtime violence. | TQM Methods | N/A. | Recommendations to improve mealtime safety, including having music therapists select and play music, resulted in a decrease in violent episodes at mealtimes. | Reduction of violent incidents per day a year after implementing changes (p < 0.001) (changes included music being played but this element could not be extracted from the other changes made). |

| Montello and Coons (1998) [48] | United States | Middle school students diagnosed with emotional and/or learning disturbances: Females (n = 2); Males (n = 14). Group A: received active then passive MT (n = 6); Group B: received passive then active MT (n = 4); Group C: received active MT throughout (n = 6). | 16 | 11–14 | 11.94 | Quasi-experimental. Participants assigned to either active or passive MT programmes embedded in school curriculum for two x 12 weekly sessions. | TRF | Active and passive MT: 45 min/once a week for 12 weeks (x two). | Active MT reduced Group B’s hostility scores significantly (the reverse was true in Group A, but Group A started with significantly lower hostility scores than Group B, suggesting that the groups were not matched well). | Group B (Active MT) reduction in hostility (p < 0.01). Group A (Active MT) increase in hostility (p < 0.05). |

| Ziv et al. (2008) [49] | Israel | Participants qualifying for diagnosis of insomnia: Females (n = 11); Males (n = 4). | 15 | 67–93 | 80.63 | Experimental. Participants randomly divided into two groups: first group received CD with progressive muscular relaxation (PMR); second group received CD with music relaxation method. Groups later switched interventions. | NEO PI-R LSQ, SAQ, SDQ, SSQ | PMR; music relaxation method. | The lower the agreeableness score, the greater the improvement in number of hours of sleep per night with music relaxation method. The higher the extraversion score, the greater sleep efficiency with music relaxation method. | Association between sleep length and agreeableness (p = 0.025); between extraversion and sleep efficiency (p = 0.042) (both for music relaxation method). |

| (3) Studies looking at music performance and personality traits associated with PDs | ||||||||||

| Cho (2021) [50] | United States | Undergraduate music performance majors: Females (53%); Males (45%); Other (2%). | 165 | >70% aged 21–23 | N/A | Cross-sectional. Participants completed questionnaires evaluating small ensemble attitudes/experience, personality, and empathy. | EQ, SECQ, TIPI, assessment of small ensemble experience and attitudes. | N/A | Non-classical musicians showed significantly higher empathy scores than classical musicians. Those who regularly perform in small group ensembles showed significantly higher empathy scores. | Association between non-classical musicians and EQ scores (p = 0.009); association between regular small ensemble playing and higher EQ scores (p = 0.007). |

| (4) Studies looking at music imagery and personality traits associated with PDs | ||||||||||

| Mullensiefen et al. (2014) [51] | UK | Participants from UK, USA, Australia, and Europe: Females (58.1%); Males (41.4%); Gender undisclosed (0.5%). Participants used in first stage (n = 512); participants used in second stage (n = 1024). | 1536 | 12–75 | 34.2 | Cross-sectional. First stage: structure of musical behaviour investigated using exploratory factor analysis; second stage: data used to determine relationships between musical behaviour and subclinical OC with INMI. | OCI-R; novel questionnaire for INMI | N/A | High OC traits were positively related to INMI frequency and disturbance. | Associations between OCD-Obsessing and Frequency (r = 0.18) and Disturbance (r = 0.29); OCD-Washing and Frequency (r = 0.13) and Disturbance (r = 0.16); OCD-Neutralising and Frequency (r = 0.17) and Disturbance (r = 0.14); OCD-Ordering and Frequency (r = 0.15) and Disturbance (r = 0.15); OCD-Hoarding and Frequency (r = 0.15) and Disturbance (r = 0.19). (Correlations r > 0.12 are significant at 5% level.) |

| Negishi and Sekiguchi (2020) [52] | Japan | University students: Females (n = 58); Males (n = 43). | 101 | 18–24 | 20.98 | Cross-sectional. Students completed questionnaires and received phone notifications six times a day for seven days asking them to record their INMI. | Gold-MSI, J-BFI, OCTQ | N/A | There was a positive association between intrusive thoughts and the occurrence of INMI. | Association between intrusive thoughts on the occurrence of INMI: Wald z (p < 0.001). |

| Category of Study | Main Relevant Conclusion(s) |

|---|---|

| Music preferences in people with PDs | Participants with PDs used music mainly for cognitive problem solving and the reduction of negative activation. |

| Music preference in people with traits related to PDs | Openness to experience was associated with a preference for blues and jazz music. |

| Using sad music for positive reasons involving others, such as celebratory events, was positively associated with openness to experience but negatively associated with conscientiousness, empathy, and emotional stability. | |

| Extraversion and lower levels of traits related to autism were associated with greater emotional responsiveness to music | |

| In one study, a preference for heavier musical qualities was associated with increased moodiness, lower self-esteem, and increased disrespect to others. | |

| Novelty seekers responded less negatively to techno music compared to non-novelty seekers. | |

| MT for people with PDs | People with BPD struggled to follow the metronomic pulse (i.e., to play in time) during music improvisation. |

| MT for people with traits related to PDs | Specifically chosen music may have helped to reduce mealtime aggression, violence, and hostility in a psychiatric prison population. |

| Music for bedtime relaxation improved sleep length for people with lower levels of agreeableness and improved sleep efficiency for people with higher levels of extraversion. | |

| People with higher levels of insecurity used music to aid cognitive problem solving and for fun. | |

| Music performance in people with traits related to PD | Non-classical music performers and those with regular small ensemble experience demonstrated higher levels of empathy than those who trained in classical music or who did not play in small ensembles regularly |

| Musical imagery in people with traits related to PDs | High levels of obsessive-compulsiveness were related to the frequency and occurrence of INMI. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haslam, R.; Heiderscheit, A.; Himmerich, H. A Systematic Review of Scientific Studies on the Effects of Music in People with Personality Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315434

Haslam R, Heiderscheit A, Himmerich H. A Systematic Review of Scientific Studies on the Effects of Music in People with Personality Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315434

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaslam, Rowan, Annie Heiderscheit, and Hubertus Himmerich. 2022. "A Systematic Review of Scientific Studies on the Effects of Music in People with Personality Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315434

APA StyleHaslam, R., Heiderscheit, A., & Himmerich, H. (2022). A Systematic Review of Scientific Studies on the Effects of Music in People with Personality Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315434